My four-year-old son once asked me if our pastor was God. I stifled a laugh, briefly imagining divinity cloaked in a Florida Gators football jersey and cargo shorts, drinking a beer on a Thursday evening. But my son’s question wasn’t as ludicrous as it first seemed. To him, our pastor is the embodiment of absolute authority; our pastor is the one who stands removed from the congregation behind a wooden pulpit, speaking seriously about Important Things. He wears a dark clerical robe. He presides over the religious rituals—prayers, baptisms, Communion, and benedictions—that seem to make the church, well, church.

Older and perhaps more cynical congregants know that church is more complicated, more mundane, and much messier than my son’s pre-kindergarten conception of things. Church isn’t all sacred ritual, hocus pocus, smells and bells—or whatever the Protestant equivalents might be. Church is nursery assignments, contentious budget meetings, and subpar potluck dinners. The pastor who thunders behind the pulpit wears Birkenstocks under his clerical robe. We, the adults, know all this.

These two postures toward the church—one a childlike reverence for authority, the other a seasoned cynicism about the mundanity of it all—are clearly at odds. They are at odds because they both perceive only part of the truth. What if there were a deeper, richer conception of ecclesial life and authority that could help us appreciate not only the exceptional nature of the church but also its fundamental ordinariness?

What in the world is the church?

Before trying to answer this question, we need to get a better handle on what we mean when we refer to “the church” and how this entity acquires authority to govern its members. Needless to say, both my four-year-old son and the more mature cynic have an inadequate view of the church. Each might get something right about the church and its authority, but each is either too immature or too jaundiced to give us a description that truly captures what we are after.

Nicholas Wolterstorff’s recent book The Mighty and the Almighty provides an alternative understanding. In Wolterstorff’s theology of public life, human institutions derive authority to exercise control over their members via delegation from God. Without that divine authority, those institutions have no binding power. Left in these general terms, of course, Wolterstorff’s political theology is almost blandly orthodox: after all, we already have Paul’s maxim that all authority derives from God. The real challenge resides in the who, what, where, when, why, and how lurking behind Paul’s claim. For instance: What institutions bear God’s authority? How is this authority transferred from administration to administration? When does that power— if improperly exercised—become illegitimate? To ask these questions is to begin to immerse yourself in a millennia-spanning conversation across the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions. When it comes to Wolterstorff’s view of the church, one particular feature jumps out. The church, according to Wolterstorff, is like no other human community. It doesn’t “belong to the social identity of any natural people.” Rather, the church is born from above through the power of the Spirit. In other words, the church did not come about because a group of people “discovered some natural affinity for each other,” or “learned of some shared occupation, plight, or project.” You do not become a member of the church because of your race, gender, or nationality, or even because you share a set of common interests with your fellow congregants. The church transcends these natural categories; it is a “foreign body” in every time and place: it should not be “the church of any nation or people.”

In a political context where religious and ethno-national interests are often conflated, this is an appealing vision. It is always helpful to hear a theological reminder that the church ultimately serves only one sovereign. Wolterstorff also manages to combine this emphasis on the independence of the church with a critical appreciation of liberal democracy. Contrary to some neo-Anabaptists accounts (think Stanley Hauerwas on one of his especially cynical days), Wolterstorff sees modern liberalism as a natural ally of the church, when properly understood. By circumscribing the authority of the state and defining the church as an utterly unique sort of institution, he carves out space (1) for the state to recognize its legitimate, Godgiven responsibilities, and (2) for the church to speak authoritatively to the political community when the state has overstepped its bounds.

That said, there remains one rather significant problem with this view of the church: it is very abstract. It seems to ignore how particular communities—including ecclesial ones—come into existence. If we say that the church is born of the Spirit, does this preclude the Spirit from working through ordinary, mundane, human means? What does it really mean to describe the church as “non-natural”? What would it look like for the church to operate as if it were not held together by certain “natural affinities,” or common objects of love? It’s hard to say.

Think about the ways that other human communities typically form. Your local CrossFit gym is populated by individuals similarly devoted to fitness (or who at least desire to be devoted). There’s a good chance the sci-fi book club at your local library is composed of folks who love Ray Bradbury and the paradoxes of time travel. Your city council contains individuals who—whether from altruistic or selfish motivations— want to participate in civic life in a more direct manner. All these communal activities exist because of some joint organizing purpose. Individuals are willing to give up time and resources for the sake of the common good achieved by the fellowship. Is the church really so different?

What if we asked Wolterstorff if his ecclesiology bears the weight of ordinariness? Can it account for all the mundane activities and interests that constitute the community, not just on Sunday morning, but also throughout the week? If you asked an ordinary congregant why they came to Sunday morning worship, or chaperoned the youth group’s mission trip, or put up with another rambling sermon on Deuteronomy, what would they say in response? Do congregants submit themselves to these things for the reasons that Wolterstorff suggests? Or are there more ordinary, proximate things that draw and keep them in the ecclesial community? And if so, what does this say about the nature of the church and its authority?

This is a rather complicated question, but it’s important to question whether Wolterstorff’s account of the church is sufficiently concrete to explain the social practices, habits, and sacrifices that make church the church. It’s well and good to say the church is born from above, and, ultimately, that is the correct answer. But before we get there, there is more to say about what the church is and how it comes to exercise authority over its members.

Communication and communion

Let’s return to the apostle Paul. If the thirteenth chapter of Romans is the locus classicus of Christian political theology, the twelfth chapter of 1 Corinthians might serve a similar role for ecclesiology. Here, Paul gives us his classic metaphor: the church is a body constituted by many parts. Each of these individual parts serves a distinct role, but each does so for the sake of the body as a whole. There’s a reason why God gifted some members with specific talents, and not others: “If the whole body were an eye, where would the hearing be? If the whole body were hearing, where would the sense of smell be?” (NRSV). And so on. Each member depends on the rest of the body in order to fulfill its own function.

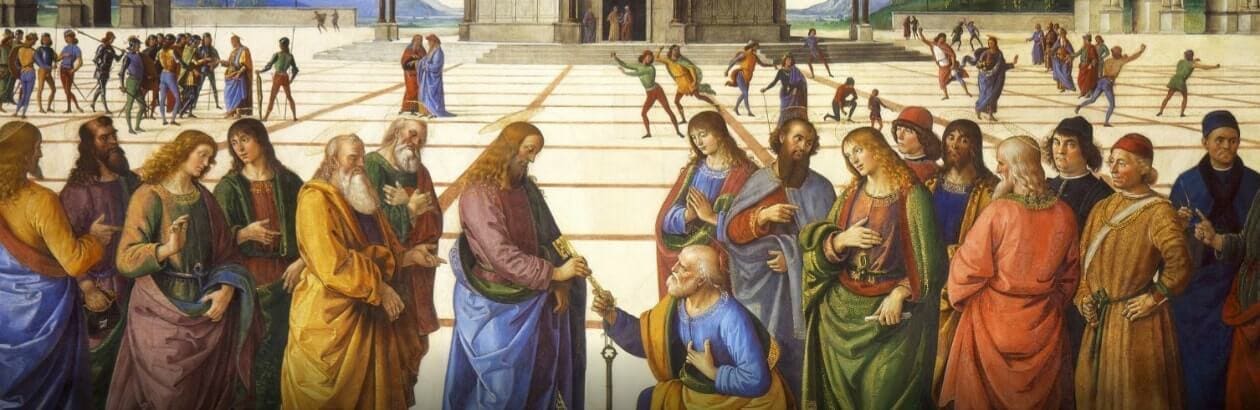

Two Reformed thinkers made a great deal of Paul’s metaphor for the church. In his Institutes, John Calvin borrowed Paul’s metaphor to explain why God created the church in the first place. God could have spoken to us “without any aid or instrument.” In fact, he could have even spoken “by angels.” Instead, God chose fallible human beings as instruments of his authority. This is why, elsewhere, Paul describes human beings as temples of God, since from out of our mouths, he speaks to us “as from a sanctuary.”

Calvin returns to this metaphor time and time again: human communication (from the Latin word communicatio, which is better translated “fellowship”) is sanctified by God’s Spirit. God ministers to us through our sharing with each other. The mutuality of this arrangement is crucial, Calvin thinks. If each individual were self-sufficient and had “no need of another’s aid,” we would all despise each other. God understood that the best way to counter human pride was to make us profoundly dependent on each other. This, in fact, is what provides for the “strongest bond of unity” in the church. God establishes the ecclesial community not through direct divine intervention or angelic teaching, but through ordinary human communication. In God’s wisdom, the strongest grace is grace mediated through fallible human instruments.

One of Calvin’s theological heirs, Johannes Althusius, picked up on this theme and applied it not just to the church but also to all of human life. Althusius was trained as a lawyer and served as a professor for many years, but later took up a position as a city leader and church elder in Emden, a coastal town on the North Sea. In Althusius’s first career as a legal academic, he made a name for himself writing about concepts like political sovereignty and absolute power. But after his move to Emden, interestingly, he revised his major political treatise to include a much longer section on the nature of human community. His term of art for community was something he called the “consociation.”

While the idea was later used in non-theological ways by political theorists, for Althusius the idea was intensely theological and very much rooted in his view of the church. The word “consociation” comes from the Latin term consociatio. It was a term that Althusius’s favourite Roman writer, Cicero, used to describe the ways that human societies organized themselves through a series of agreements—or covenants—ordered to some common good. In Althusius’s own day, the idea of consociation was often used to describe the nature of the church—specifically the way that the sacraments and the Holy Spirit bind the ecclesial community together in service of God and the world. Althusius transposes spiritual fellowship into the political community, noting the harmonies that result when persons with complementary gifts communicate those things among each other. The gifts of God for the polis of God.

This background helps to explain Althusius’s fascinating discussion of the ways human communities arise, and how they come to exercise authority over their members. He explicitly borrows from Calvin’s description of the church to talk about the basis of all human sociality. It’s no coincidence, he argues, that each of us possesses different skills, personalities, and desires. This all comes from God, who chose to “distribute his gifts unevenly” among us so that we would recognize our need for each other. Echoing Calvin’s description of the church, Althusius writes that there’s a reason we were not trained by angels: we have each other for that purpose.

The crucial point here is that diversity isn’t a bug—it’s a feature designed to strengthen the relational bonds that hold us together. Althusius asks his reader: “If each did not need the aid of others, what would society be?” In other words, living well in community with each other involves a continual process of mutual recognition and humble exchange. I share my gifts with you (the ones you lack), and you share yours with me (the ones I need). Without this mutual recognition of need, democratic life would be a shapeless egalitarian void, lacking the social exchanges and practices that give the community its very life.

This recognition, and the sharing that follows, allows us to enjoy things we couldn’t on our own. In society, there can be no autonomous individuals, no blank slates, no noble savages, no brutish state of nature blood-red in savage civil war. Instead, the picture that Althusius paints is that of a body with an assembly of mutually dependent parts, held together—and this is quite important—by something he calls the “spirit” of the community. This spiritual force comes from a variety of sources: the Decalogue, civil laws, and (most importantly) the communication of gifts among individual members. In short, the spirit draws the citizens of a community together in a way that is deeper than just the physical goods they share in common. Just as Paul and Calvin argue that the Holy Spirit vivifies the ecclesial body, Althusius argues that without the spirit of the political community, its body too would wither away and die.

Rooting out the devil’s agents

If the community is a body, we might want to ask, who gets to serve as the head? This is where things get even more interesting.

For someone like Althusius, we first have to remember, democracy was a four-letter word. Despite the attempts of later historians to convert Calvin and Althusius into liberal democrats, these early Protestants would’ve recoiled at the suggestion that their writings defended democratic polity. They had difficulty imagining a democratic society that preserved the hierarchical institutions they believed were the backbone of civil society. That difficulty is, well, understandable. That said, looking back from the vantage point of late modernity, we can identify specific features of Calvin’s ecclesiology and Althusius’s political theology that are at least friendly to modern democratic life and norms.

One of these democracy-friendly ideas is Althusius’s view of authority. If we accept his idea that human communities come together when diversely gifted individuals recognize their need for each other, we still have to ask who wields authority in these complex relationships. On this point, Althusius constantly reminds his readers that the common goods of the fellowship—whether ecclesial or political— come first. Any exercise of authority within the community must be for the sake of the body as a whole. Private interests should never drive the agenda. The community can appoint representative individuals to oversee practical matters, but these individuals are servants of the community, not the other way around.

The implication of this view is that if powerful individuals try to game the system for personal gain, create dissension, overstep their responsibilities, or marginalize the powerless, the community must exercise its God-given authority in response. Tyrants—even the petty ones— are a cancer to the community. If human communities are the basis for human flourishing, if social relationships are themselves gifts of God’s Spirit, then individuals who attack them must be rooted out. (Althusius goes so far as to describe these individuals as agents of the devil.) And, just as we do not wait around for angels to instruct us, neither should we wait for divine intervention to chasten the vicious tyrants in our midst. That is our responsibility as members of the body.

Let’s make this more concrete: How does this view of the ecclesial community help us be better disciples, form better churches, and act better as corporate or individual citizens?

I’m confident Althusius would’ve been quite happy to endorse Wolterstorff’s description of the church as an institution born from above by the power of the Spirit—the community to which God has specifically gifted his presence, his sacraments, and his Spirit. At the same time, the church comes together in ways that are analogous to other human communities. We (in principle, at least) recognize Christ as Lord, desire to live in accordance with the norms of Christian discipleship, and hope to share in the fellowship promised to us through the power of the Spirit. The content of these common goods may differ from those in the political community, but they function in a similar way. These two communities are two different species, we might say, of the same genus.

If all of this is true, it shouldn’t surprise us that the ways we are formed by the church affect our other relationships—and also the ways we are malformed. This is the flipside: vicious forms of power corrupt all sorts of communities, not just the church, and not just the political community. Since structures of authority do not drop out of heaven, since we are not in fact trained by angels, we must be on the lookout for the ways human communities may have warped our desires and our very selves. Since authority emerges from the ground up, we’ll need to work doubly hard to pursue safeguards and structures that protect social relationships from the forces that threaten them.

In a very specific sense, we might describe this view of the church as democratic, although not egalitarian. In other words, structures of authority emerge as we recognize that God has given members of the community different gifts and callings. The (rather difficult) work of living well together entails ensuring that the institutions and norms that structure society are just and allow members to participate in the common good in their own unique ways.

This is where the perspectives of my four-year-old son and the more cynical adult must converge. Both get something right and something wrong. The cynic correctly understands that the church is not perfect, infallible, or immune to human pettiness or corruption. Church life requires compromise, sacrifice, and the ability of imperfect, sinful congregants to find ways of living well together.

A young child is likely too immature to understand all of this. Yet there is something that my four-year old son, in his guileless question to me, did understand. A child can sense that the ordinariness of the church masks a deeper reality: the Spirit at work in the mundane. A child can sense, but perhaps can’t explain why or how, there’s something special, sanctified, and meaningful about the church—and that this is no less true because of its ordinariness. God’s grace can be communicated through a mediocre sermon, through Communion wine purchased at Costco, through the mutual accountability offered by a trusted friend in a time of testing, or through the regular exhortation to solidarity with the poor in an age that instinctively reveres the powerful.

These examples reveal a way of life that forms us—sometimes for good, and sometimes for ill. What they also reveal, perhaps especially when they fall short, is a set of communal norms and relations that are greater than the sum of their parts. Individual talents and vocations are given a significance and purpose that they lack apart from the social relationships that exist in the ecclesial community.

Perhaps just as importantly, we have to recognize that the church ought to give us a model for communal correction and mutual accountability. The church, of all communities, should be intimately aware of the ways sin and vicious power can corrupt human fellowship. It shouldn’t be a surprise that a church elder from Emden was one of the first political thinkers to argue that communities have a God-given obligation to defend themselves against vicious powers. After all, Althusius’s defence of political resistance to tyranny derives from his Calvinist conception of the church.

Here, it’s important to remember that Calvin’s and Althusius’s claim that we are not trained by angels has a double meaning: it shows us not only that human beings may mediate God’s authority to his people but also that no one can claim unmediated authority over another. The powerful who forget this principle should have an entire flesh-and-blood community to answer to. Democratic resistance to unjust power should have its seedbed in the life of the church. Protestantism catches a lot of flack for allegedly breaking with traditional conceptions of authority, but this is one social outcome that heirs of Luther, Calvin, and Althusius ought to embrace. Here, we might even take notes from the work of the Protestant ethicist Luke Bretherton and the theologically attuned atheist Jeffrey Stout, who both show how the social practices of Christian churches can form congregants into prudent, courageous democratic citizens. The lesson here is that democratic life and democratic responsibility ought to begin in elders’ councils, congregational budget meetings, and volunteer nursery assignments. Calvin and Althusius may have shrunk back from the d-word itself, thanks to its historical connotations, but in at least one very real sense, we have the structures of modern democratic life because these Reformers valued mutual accountability, popular governance, and the life-giving work of the spirit within the communal body.

Even the best of communities can only give us half-glimpses of the full reality of these things. Human communities are of course just that. And yet, it is the humanness of the church that gives us reason to hope—hope that this ordinary life is shot through with the in-breaking grace of the life to come.