B

Are you not in the hollow of my mantle?

—Mary to Juan Diego in the Nican mopohua

Beautiful as it is that the Milky Way was once known in England as the Walsingham Way, the fact that a pre-Christian shrine to Mexica mother goddesses now honours the Virgin Mary in Mexico City is no less momentous in scope. And so, to retain my Marian pilgrimage title this year, I made my way not just northward but southward to that Mexican Zion, where Mary also asked someone—not an English noblewoman in this case but the indigenous peasant Juan Diego—to build her a Holy House. This is now the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, which has easily eclipsed its namesake, a smaller site of Marian devotion named Guadalupe in Spain. Indeed, the Mexican shrine of Guadalupe, according to official and unofficial reports, is the most visited Marian shrine in the world. The fact that Mary’s home in Nazareth so successfully replicates itself must be a frustration to those who oppose the one reared in Nazareth himself.

As with Walsingham, my warm-up for Guadalupe was threefold. First came a visit to Chicago’s premiere Hispanic parish, St. Francis of Assisi Church, where the cloak of the joyful Juan Diego unfurls just above the high altar. The church was generously populated for a weekday Mass, and sculptures of the tortured Christ were festooned with visceral votive prayers, some of which were even inserted into the ribbons of his flayed skin. Then came a trip to Sante Fe, to the oldest Guadalupe shrine in North America. It was mid-September, so the blazing yellow aspens in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains matched Mary’s halo in the Guadalupe statue that faces the town. I entered the precincts of the shrine and experienced—for a moment at least—not the playground of the prosperous but the refuge of the reverent. A family of five had piled into one pew to pour themselves out in prayer, transforming the building from a tourist stop into a temple.

Wisconsin has an impressive Guadalupe shrine as well, though much newer, set amid the Mississippi bluffs. I managed to get there during October’s splendour, when Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke—who has locked horns with Pope Francis—was giving an address. One academic study claims that the shrine is more a “citadel of orthodoxy” and a “rebuttal to modernist architecture” than a reflection of grassroots devotion, concluding it is not yet “a true pilgrimage site.” Yet, thanks to the Memorial to the Unborn that draws numerous devotees, even the skeptical author of that study concedes that a popular groundswell is lending the shrine increasing clout. I found Cardinal Burke’s usage of the Guadalupe tradition to illustrate classical Christian sexual ethics not forced but persuasive. The only disappointment for this visitor was that the crypt of this magnificent neoclassical chapel, where the cardinal’s address was delivered, was not appropriately sepulchral but frustratingly well lit. With these three trips behind me, I felt I could at last make my way to the shrine of Guadalupe itself.

In The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James describes Catholic sacred spaces as “so many cells with so many different kinds of honey.” The architecture of the 1976 Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, with its golden hexagonal clusters, seems inspired by that very remark. As I entered, a reverent custodian swayed with her broom, sweeping a patch of the basilica’s vast interior in circling motions that resembled dance. Once I was seated, a well-dressed funeral procession approached the altar to sing reverent, guitar-driven anthems that were fathoms deeper than the guitar-driven praise songs of my own culture. Their gratitude reverberated in the space, followed by a pleasing silence that filled the basilica even while it remained well populated. I then made my way behind the main altar to the moving sidewalks that bring pilgrims directly beneath the original image while hastening forward those who linger too long.

With respect for those who insist that the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe was not painted by a human, and with a full belief in the possibility of miracles myself, I think the tilma hanging in the basilica today was very likely painted not by God the Father himself—as many have claimed—but by a mortal artist. Still, with equal respect for the punctilious detective work of art historians, God the Father is the author of all existence, in which the Virgin Mary holds a preeminent place, so in a way the legends about the image’s divine origin are true nonetheless.

What Really Happened at Tepeyac?

The long history of the controversies over the image of Guadalupe was conveniently laid out for English readers decades ago in Mexican Phoenix by the Cambridge historian David Brading. More recently, Jeanette Favrot Peterson has offered an exhaustive and gorgeously detailed analysis of the image itself in Visualizing Guadalupe. Both books are scholarly masterpieces. Brading reverently concludes his study by suggesting that in the same way that the writers of the Gospel accounts left their own character on inspired texts, so we need not be scandalized that there are clear signs of human intervention in the image of Guadalupe.

The reason these facts have taken centuries to absorb is straightforward enough. It is all due to a book first published in 1648, Miguel Sánchez’s Imagen de la Virgen María. This is the origin of the more famous story of Mary appearing to a native, Juan Diego, in 1531. The Virgin tells Juan to report to Mexico’s first bishop, Juan de Zumárraga, that she wanted a house built for her at Tepeyac, a hill to the north of what is now Mexico City. The receiver of the Annunciation thereby became herself the announcer. Sánchez relates how Juan was met with episcopal skepticism, but at the Virgin’s bidding he returned to the bishop again, and then a third time with a bundle of flowers given to him by Mary, flowers that had curiously bloomed in December. Any resemblance in Sánchez’s account to the story of Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh, or to the apostle John’s vision of Mary on Patmos, is deliberate. When Juan Diego unfurled these flowers—which he had kept bundled into his workaday cactus-fibre garment known as a tilma—the image that hangs in Mexico City today, Sánchez reports, miraculously appeared on it.

The receiver of the Annunciation thereby became herself the announcer.

Sánchez wrote in Spanish and presumably derived his story from witnesses, “the eldest and most trustworthy persons of the city,” who testified to its veracity. Though not scholarly by modern standards, Sánchez’s account is itself a profound achievement of theology and devotion, inaugurating an intellectual tradition that has continued ever since. It was frequently reported that Sánchez, who lived the latter part of his life as a hermit at the shrine of Guadalupe, knew all of St. Augustine’s writing by heart. Considering the popularity of the image of Guadalupe, it might even be possible to name Sánchez among the most influential “art historians” of all time. We moderns specialize in critiquing, measuring, and dissecting devotion, and there is a place for that; but Sánchez was instrumental in generating the greatest devotion to any image in the Americas, and there is something to be said for that as well.

A similar Nahuatl-language account of the image known as the Nican mopohua (which translates to “here is recounted”), by Luis Lasso de la Vega, is in fact dependent on Sánchez and appeared the following year, 1649. This account reverently repeats, and lovingly embellishes, the legend of Juan Diego, to glorious effect:

When [Juan Diego] arrived in her presence, he was filled with the greatest wonder at how her perfect beauty surpassed all things. Like the sun her clothes radiated, as if throwing out rays, and with these rays the stones and rocks on which she stood were radiant with light. The earth which surrounded her appeared resplendent like precious stones, as if bathed in the light of the rainbow. And the mequites and nopales and other bushes which were there seemed like emeralds and their foliage was like turquoises, and their trunks and branches shone like gold.

Delightful as the 1648 and 1649 accounts may be, no one has been able to explain with satisfaction the complete silence in the sources about Juan Diego for more than a century before Sánchez picked up his pen. It is certainly possible that indigenous narratives of an actual apparition and a miraculous image simply went unrecorded until 1648. History need not be limited to what is captured by Spanish stenographers. But such an appeal to oral tradition is complicated by a 1556 written account, discovered in 1846, chronicling a conflict between an archbishop (Alfonso de Montúfar) and a Franciscan (Francisco de Bustamante) over the image of Guadalupe. The latter, suspecting devotion to the image was risking idolatry, attributed the painting to a native artist named Marco. Moreover, the existence of just such an artist is independently confirmed by “a list of thirty-six artists listed in the Anales . . . of Indian districts in Mexico City.”

More than a few have suggested that the survival of the name of a native artist of such importance, Marco Cipac, might itself be considered a miracle worthy of celebration.

Jeanette Peterson further specifies this likely artist’s name to be Marco Cipac (de Aquino), and she suggests he deliberately skewed the image, including Mary’s olive skin colour, in an indigenous direction. This is not a new suggestion. Mexican historians in centuries past, themselves conservative and pious Catholics, also pointed out that the existence of the artist Marco calls Sánchez’s account of the image’s miraculous production into question. These historians were mercilessly attacked for this presumably impious claim, their careers ruined; but that doesn’t make them wrong. Even so, more than a few have suggested that the survival of the name of a native artist of such importance, Marco Cipac, might itself be considered a miracle worthy of celebration.

Whatever conclusion we come to about the image’s origin, a few things are not under dispute. Even if Sánchez’s date of 1531 for the apparition is historically questionable, there was certainly a shrine at Tepeyac by 1555. Moreover, a chance discovery at a Oaxaca thrift store in 1944 of a copper plate bearing the image of Guadalupe, dating to 1613–1615, makes the existence of the image long before Sánchez’s 1648 account quite certain. We also know that there was a pre-Christian Mexica shrine to the region’s earth deities gathered under the name Tonatzin, which—in some translations—is a perfect match for the name “Mother of God” long assigned to Mary. There is no easy answer to whether this was a Christianizing of paganism or (as critics claim) the reverse. Either way, the Christianization of Mexico makes the story of the Virgin and Juan Diego at the very least symbolically true, even if its art-historical claims, technically speaking, appear to be inflated.

A Marian Kaleidoscope

Protestants who reflect the original Franciscan suspicion of the image of Guadalupe by insisting all this is “syncretism” or “goddess worship” might—following a critical assessment of the jumbotrons of megachurch preachers—take a look at the early accounts such as the Nican mopohua. In it the Virgin Mary’s leading insight is painstakingly direct:

I want very much that they build my sacred little house here, in which I will show Him, I will exalt Him upon making Him manifest, I will give Him to all the people in all my personal love, Him that is my compassionate gaze, Him that is my help, Him that is my salvation.

Not only are Mary’s express words centred on Christ, but so is the image itself. The ribbon around her waist is an indication of pregnancy. Christ is the literal centre of the image, albeit in uterine form.

Guadalupe offers an even greater challenge to those for whom the phenomenon of colonization, lazily construed, is supposed to explain everything.

But Guadalupe offers an even greater challenge to those for whom the phenomenon of colonization, lazily construed, is supposed to explain everything. It would be easy to conclude, owing to the fact that Sánchez hails Cortés as God’s answer to Martin Luther, that Guadalupe is just a cloak for Spanish aggression. But the history of Guadalupe does not end with this facile glorification of the conquistadores. She became the image that inspired the 1810 Mexican War of Independence from Spain. The creole priest Miguel Hidalgo named her the “General Captain” of his armies, lending credence to the claim that Guadalupe sided with “the lower clergy, mestizos, landless farm workers and Indians.” Moreover, in the twentieth century, Our Lady of Guadalupe in turn became an image of liberation theology. Peterson rightly calls this development a “stunning reversal.” As if that were not interesting enough, today Our Lady of Guadalupe takes on new interests. Nichole Flóres argues that she can “mediate differences between enormous religious, cultural, and political rifts” and offers “a vigorously participative vision of democracy.”

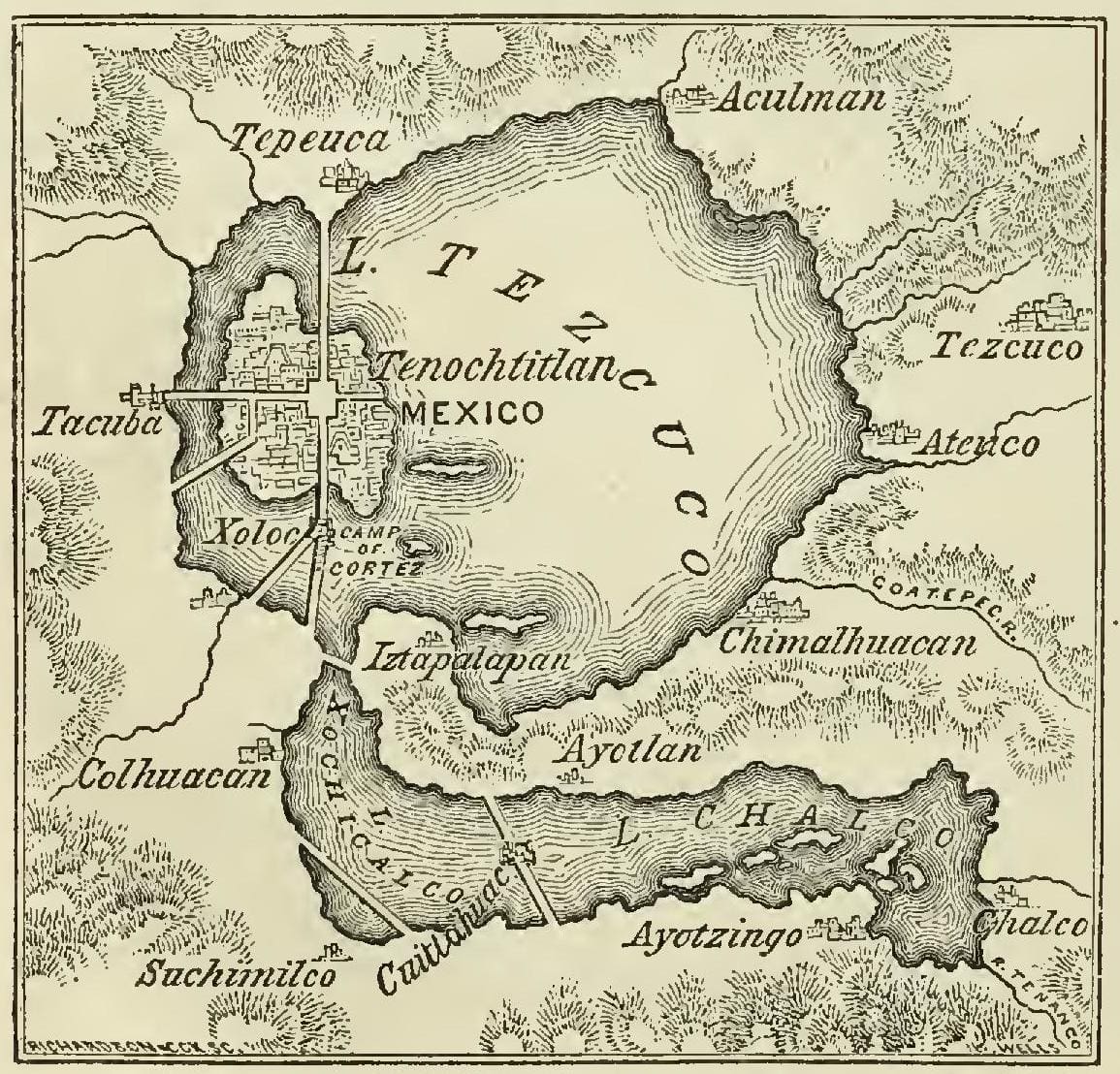

We could add to this how Our Lady of Guadalupe is also a symbol of resistance to Mexico City’s notorious pollution and sprawl. In the sixteenth century, what is now Mexico City was largely covered by Lake Texcoco. A long of strip of land went north from the centre of the city to the shrine at Tepeyac, where Guadalupe stands today. Lake Texcoco has long since dried up, but the Tepeyac trail still exists in the form of a miles-long park of carefully managed greenery. Indeed, it is not unfair to say that it is only because of Christianity that this indigenous pathway survives at all.

But that indigenous culture did not endure without massive, and necessary, alteration. Following that strip southward takes you to what remains of the Aztec capital once known as Tenochtitlán. Within it, the Temple Mayor—the very fulcrum of Mexica cosmology—boasted nearly seven hundred human skulls unearthed in 2015, testifying to human sacrifice at near industrial scale, even to the point of requiring a skull rack. The same Nahuatl word for this grisly display was used to translate the word “Golgotha” in the Gospels, testifying to the end of sacrifice. Crosses were even placed in cuauhxicalli, the receptacles that once held freshly extracted human hearts (as at Cuernavaca, Morelos). Such accommodating manoeuvres of Franciscan missionaries both honour and amend Mexica pre-Christian notions of sacrifice and are far less patronizing than secular assumptions that the worldview of both the Mexica and the missionaries was false.

The fact that Mary is no goddess means that she requires no sacrifice and is herself dependent, as all humans are, on the sacrifice of the cross.

Indeed, today, after visiting what is left of the Temple Mayor, one can walk just a few dozen paces to the Catholic Cathedral of the Assumption, where the Eucharist is perpetually exposed, a practice that is itself an answer to the sun worship of the Mexica. For all the clerical failures in the present, we can express gratitude that the training of priests today does not involve techniques for how to remove a living human’s heart. So, yes, Guadalupe accommodated indigenous culture, but also necessarily corrected it. The fact that Mary is no goddess means that she requires no sacrifice and is herself dependent, as all humans are, on the sacrifice of the cross.

A Deeper Meaning Still

Back at the shrine of Guadalupe, I aimed to honour this end of human sacrifice by making of myself a living one. If the ancient Christians ingeniously allegorized Old Testament stories of Canaanite conquest, seeing in them a metaphor for the struggle with deadly thoughts, perhaps the same can be done for the Spanish conquest (with the help of the “indigenous democracy” of Tlaxcala) of the Aztecs. So, without glorifying the violence of the conquistadores, and without excusing Aztec bloodlust either, I took up my own struggle with thoughts instead, and a mighty struggle it was. How much easier it is to opine about former conflicts—attempting to steer a sophisticated course between Black and White Legends—than to take on conflicts within oneself.

Guadalupe, when approached as a place for contemplative prayer, is a confrontation with that river of wolfish thoughts, both good and bad, that hold us in their thrall.

To do so, I retreated from the main basilica into the quieter chapel of San José behind it. There I was met less with an image of Mary than with a grisly, wounded Jesus and the most intriguing image of St. Joseph that I have seen. If Mary’s mantle so frequently covers her supplicants, it turns out that St. Joseph’s mantle can as well. This painting was commissioned in gratitude to St. Joseph for saving the citizens from plague in the early nineteenth century, and I would not dispute such an event or such a dedication. But in silent prayer before this painting, prayer that I found (and still find) extremely difficult, Joseph’s black shroud—enclosing even sun, moon, and stars—became an invitation into the emptiness of Christ. We are “suspended between the abyss of divine infinitude” and “our own nothingness,” wrote Philaret of Moscow. Or as M. Basil Pennington once put it,

We have to be willing to experience our nothingness, the nada of John of the Cross, to be able to come to the experience of the call of God which is the core of our being, the deepest self, our person at its roots. . . . If we are willing to experience our sinfulness, we can truly experience Christ as our Savior and know deeply the joy of salvation.

I suppose, then, it would be fair to say that at the shrine of Guadalupe I experienced nothing. “The true sacred attitude is one which does not recoil from our own inner emptiness,” wrote Thomas Merton, “but rather penetrates into it with awe and reverence.” What we call thought is very frequently—I’m tempted to say usually—the determined avoidance of such emptiness. The word “Guadalupe,” hailing back to that original site in Spain, means “River of Wolves.” Guadalupe, when approached as a place for contemplative prayer, is a confrontation with that river of wolfish thoughts, both good and bad, that hold us in their thrall.

A pilgrimage to the Mexican Guadalupe can therefore be an escape into the darkness of the original Guadalupe image, which is still in Spain. This Black Madonna—according to tradition—was crafted by St. Luke himself and kept in a cave for six hundred years before it was disinterred in Extremadura. The dark wisdom of Christian contemplation has been buried underground for centuries as well and is being unearthed at last in the present. The ubiquitous images in Mexico City shrine shops of the black-robed Lebanese hermit St. Charbel (1828–1898), his eyes aimed downward, reinforced this contemplative message in an unexpected way.

What I am describing is not a Buddhist nothing, even if Buddhism comes far closer to this wisdom than worldly conceit. Admittedly, there was a certain kinship between the nothingness I experienced at Guadalupe and the nothingness I experienced at Bodh Gaya, the site of the Buddha’s awakening; but it was distinct nonetheless. So distinct, in fact, that one former Buddhist attributes to Marian nothingness a sort of conversion. “I hadn’t prayed in almost 30 years,” writes one author of The Way of the Rose.

I had meditated. I had contemplated the dead. I had invoked all kinds of protective spirits in the traditional Buddhist way. But in all that time I had not once, very simply, asked any Higher Power for help. . . . The rosary made it easier than it had ever been on the meditation cushion to enter the quiet inner space I had cultivated as a Buddhist monk.

I, too, have experienced in Mary an answer to the challenge of Buddhism. Cynthia Bourgeault uses the New Testament word kenosis (self-emptying) to describe Christian contemplative prayer, which is more a simple letting go than any forceful effort of renunciation. “Unlike a more Buddhist version of this spiritual motion,” she explains, “kenosis has a certain warm spaciousness.” This may be the nothing that St. Paul refers to when he says, “If anyone thinks he is something, when he is nothing, he deceives himself” (Galatians 6:3). This is no barren nothingness, but a nothingness that is both chaste and erotic at once—because it brings forth the Christ in the virginity of faith.

One former Buddhist attributes to Marian nothingness a sort of conversion.

It is so very easy to get this wrong. Thomas Merton’s warning remains indispensable:

A person [cannot] become a contemplative merely by “blacking out” sensible realities and remaining alone with himself in darkness. First of all, one who does this of set purpose, as a conclusion to practical reasoning on the subject and without an interior vocation, simply enters into an artificial darkness of his own making. He is not alone with God, but alone with himself. He is not in the presence of the Transcendent One, but of an idol: his own complacent identity. . . . An emptiness that is deliberately cultivated, for the sake of fulfilling a personal spiritual ambition, is not empty at all: it is full of itself. . . . Such “emptiness” is in fact the emptiness of hell.

One thinks here of the black house of Moctezuma II, the windowless, basalt-lined chamber where the emperor meditated, consulted shamans, and presumably foresaw the arrival of the Spaniards who, with the help of Moctezuma’s indigenous enemies, became his ruination. Those black obsidian mirrors also come to mind, which in Mexica lore formerly represented the deity Tezcatlipoca, “Lord of the Mirror,” to which living human hearts were once offered.

Still, there remains a uniquely Christian emptiness, for it was precisely those obsidian disks—now redeemed—that were placed at the centre of crosses in places such as the Franciscan mission at Ciudad Hidalgo, Michoacán. I can think of no better example of a nihilism being replaced with the radiant no-thingness of the life-giving cross. “True emptiness,” Merton writes, “is that which transcends all things and yet is immanent in all. For what seems to be emptiness in this case is pure being. . . . The character of emptiness, at least for a Christian contemplative, is pure love, pure freedom.”

This has everything to do with Our Lady of Guadalupe, for all such accounts of Christian emptiness are, of course, fundamentally Marian. The classic articulation comes from Caryll Houselander’s 1944 work, The Reed of God:

[Mary’s] is not a formless emptiness, a void without meaning; on the contrary it has a shape, a form given to it by the purpose for which it was intended. It is emptiness like the hollow in the reed, the narrow riftless emptiness, which can have only one destiny: to receive the piper’s breath and to utter the song that is in his heart. It is emptiness like the hollow in the cup, shaped to receive water or wine. It is emptiness like that of the bird’s nest, built in a round warm ring to receive the little bird.

If Our Lady of Guadalupe has functioned as an emblem for New Spain, a symbol of Mexican independence, a banner for liberation theology or conservationist ecology, perhaps she can serve as a symbol of the depths of contemplation as well.

Street Prayer

Emboldened by the nothing I experienced at Guadalupe, I decided to take this Christian lesson in emptiness to the street. As the city began its celebrations of Día de los Muertos, the virtuosic papier-mâché displays and the elaborate costumes functioned for me as they have long been intended: as memento mori, reminders of my own eventual death, and the hope in Christ that lies beyond it. “Those who love true life,” to cite Merton once more, “frequently think about their death. Their life is full of silence that is an anticipated victory over death.”

Amid the mandatory museum visits for this art historian, I passed several “liberated zones” where masses of pot-smoking citizens of all ages gather, labelling their makeshift precincts, almost daring police officers to arrest them. The tone of these gatherings was riotous, and they even beckoned me to join them. This I did not do, but I was sufficiently challenged by these gatherings that I decided to playfully surpass them. I firmly planted myself near—but not in—one such cluster, seeking to be grounded only by the practice of chemically unaided contemplative prayer.

And so, surrounded by traffic and pedestrians, I sat down and fixed my attention on the Church of San Hipólito across the street, the site of a battle between the Mexica and the conquistadores. In my case, however, it became the site of a battle between internal verbiage and silence. I entered the struggle with thoughts, or rather the struggle to not struggle with thoughts but to surrender each one of them—good or bad—to the Father of lights. After twenty difficult minutes, the peace of Christ, which the world has not, reasserted itself in my heart. More settled than the stoners, I then crossed the street to enter the church.

San Hipólito has a marked devotion to St. Jude, illustrated by dozens of statues both on display and for sale in various sizes. His green garb, and the subterranean devotional space brimming with candles, contrasted richly with the recreation that was taking place on the streets above. As a reminder of my street prayer experiment, and a mark of my determination to perpetuate it, I purchased a small figurine of St. Jude pointing to the image of Christ that he bears. You might call it contemplative kitsch.

As the empty womb of Mary enabled her to conceive by the Holy Spirit, so the blankness of St. Jude’s robe permitted the Christ image to be impressed on it, and so the plain cactus fibres of Juan Diego’s tilma made it possible for him to bear the famous image as well. Saints Jude and Juan imitate Marian nothingness, and so their faith brings Christ again into the world. “The Christian contemplative path,” writes Brian Robinette, “is one of purgation unto union, kenosis unto theosis, nothingness unto fullness.”

“Awake, O Sleeper!”

Back at home, at about four in the morning the night after my return from Guadalupe, my nine-year-old son hurled himself into his parents’ bed, announcing a disturbing dream. Because dads are not as much help on these occasions as they might wish to be, my wife enveloped his head with her arms, ensconcing him as if in a pyramid. Reports of the dream’s details lost their importance as she quietly retorted in rhythmic whispers, “It was just a dream.”

The church still offers the only lasting comfort from humanity’s nocturnal illusions.

This is what happened to me at Guadalupe, and at Walsingham, and what happens to everyone who goes to this “numinous network of Christian fortresses” in faith, for the church still offers the only lasting comfort from humanity’s nocturnal illusions. Everything else—the sacrificial spasms of the Mexica, the colonizing violence of conquistadores, the royal ravages of Henry VIII, the pretensions of passing nation-states, the rapacious revenge fantasies of Diego Rivera’s Marxism, the algorithmic amphetamines of digitized capitalism, the technologically dependent hallucinations of the post-humanists, or my own self-centred schemes for what I think of as “success”—all this is just a dream. Thoughts delude us, even the presumably good ones. The naked sobriety of Christian contemplative prayer, which the Virgin Mary teaches, remains the truest awakening.

If you, too, have escaped from the lupine river of worldly illusion, if you have been weaned from such fantasies by the arms of the church, in whatever manner she has embraced you, please start your Marian pilgrimage planning for 2025.

Are you really going to let a mere Anglican win again?