A

As we await the birth of the Christ child this Advent, we wait with his mother. In four pieces over the next four weeks, we’ll travel to four corners of the world—from Illinois to India, from Loreto to London—where we’ll wait with Mary. But the Virgin has been, and remains, a stumbling block for some. If the wary can’t be cajoled into at least reluctant accompaniment, the journey—like a long-awaited family vacation where one beloved sibling just couldn’t make it—will lose much of its appeal. So, in order that as many people as possible will join in this global pilgrimage, a preliminary question must come first.

Does the love of Mary compete with the love of Jesus? It can—it even has, I admit it—but it need not. Love is no zero-sum game, as if our doling some percentage points to the Virgin will detract from the remaining percentage devoted to the Christ. Love is not a prepaid cell-phone plan that penalizes excess. Instead, the love that abounds to Mary rebounds to her son and back again. In the same way, the more I love my children, the more I love my wife; the more I love my colleagues, the more I love my students; the more I love Orthodox, Catholic, Pentecostal, or Reformed Christianity, the more I love my own Anglican tradition; the more I love Venice, Thessaloniki, or Cairo, the more I love my hometown; the more I love the verdant thrush of summer, the more I love how winter sunsets redden snow-capped rooftops; the more I love my enemies, the more I can love myself. That’s how love works this side of hell.

Love is no zero-sum game, as if our doling some percentage points to the Virgin will detract from the remaining percentage devoted to the Christ.

But hell’s envious economy has shaped us. “You’re really into Mary,” a friend once said to me with concern—concern that my interest in the Virgin was no passing fancy but was developing into a lifelong pursuit. It seemed he was intimating I should move on to other subjects, especially seeing that I teach at a Protestant institution. I had met such puzzlement before, but this was friendly fire from a fellow believer (who you can thank or blame for this four-part series). But indeed, it is precisely because I am aware of the view of the classical Reformers that I can’t just move on. As Catholics never tire of reminding Protestants, Luther, Calvin, and even Bullinger and Zwingli all had a deep respect and honour for the Virgin Mary inherited from the tradition they were critiquing. Catholics, however, don’t as frequently point out that this also means Protestants need not convert to Catholicism but can continue to love Mary where they are today.

Mary Is Also Protestant

“We revere her [the church] as our mother,” insisted John Calvin. It is not incidental that Matthew Barrett begins his massive book outlining the catholicity of the Reformation by citing this line. Calvin, who happily called Mary the “treasurer of grace,” uses the female gender for the church likely because the Virgin herself has been a shorthand for the church in both the Bible and the tradition. As Israel was represented as a bride (Isaiah 54:5–6; Jeremiah 2:2; Ezekiel 16:8), so Mary continues this representation as the church (see the entire Gospel of John, 2 Corinthians 11:2, Ephesians 5:31–32, and Revelation 12:1–17). It is as useless to try to literalize or lock these metaphors down; let them resonate instead. She is both a singular historical woman and a figure of God’s wise and loving intent to save us all.

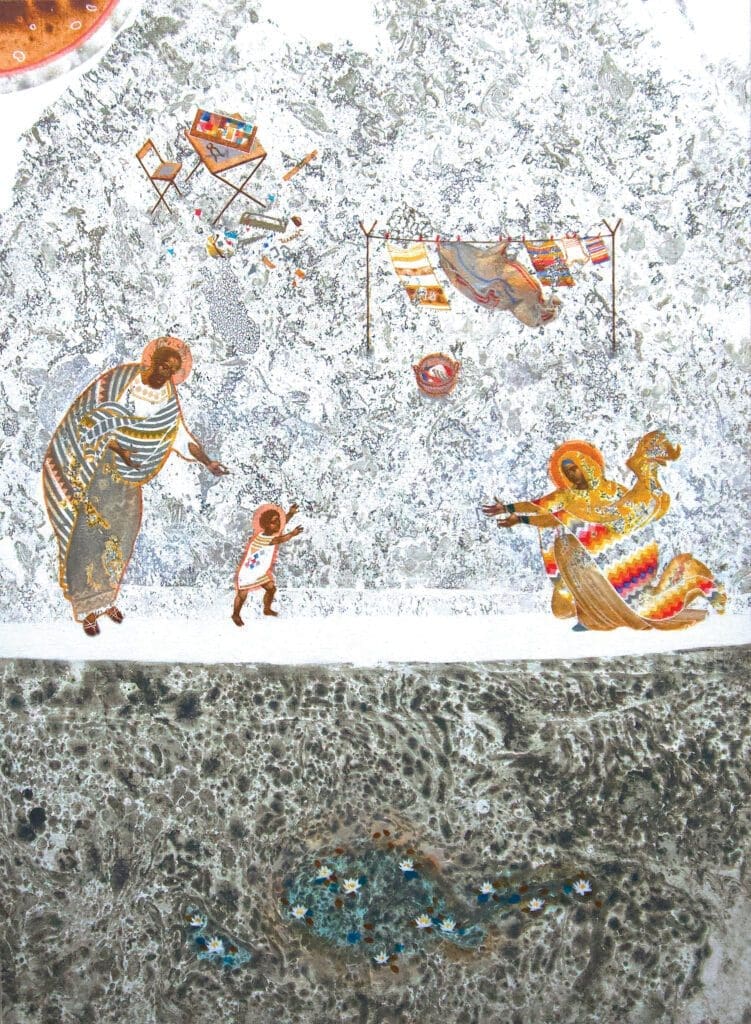

As Addison Hodges Hart and Solrunn Nes elucidate so beautifully in their book Silent Rosary, Mary is thrillingly polyphonic. She can be read allegorically as the church or morally as the soul. Mary is all these things at once, without ever losing her historical character, her irreducibly personal dimensions. She can even be understood, I’ve argued at length, as the created wisdom of Proverbs 8, and not to make this connection, moreover, risks the Arian heresy. Here is Augustine in book 15 of Confessions: “So there is a wisdom created before all things which is a created thing, the rational and intellectual mind of your pure city, our ‘mother which is above and is free’ (Gal 4:26).” This is not to confuse the historical Mary with this ancient wisdom but to felicitously connect her to it. If I compare my wife to a melody, please don’t tell me you think my wife’s name is actually Melody, or that I actually married a song. “Whatever is said of God’s eternal wisdom itself,” wrote the twelfth-century Cistercian Isaac of Stella, “can be applied in a wide sense to the Church, in a narrower sense to Mary, and in a particular way to every faithful soul.”

Considering these expansive Christian understandings of the Virgin, it is a small wonder that she keeps showing up where she is supposed to be absent. Not only in the Tree of Jesse window at Chartres, but also (as one art historian reveals) in trees of Jesse in Puritan prayer books like the 1578 Book of Christian Prayers, and even emblazoned on the ceilings of staunchly Puritan fish merchants as well; not only in Dutch cathedrals that stayed Catholic, but also in the ones that turned Protestant. She appears clandestinely in Reformed paintings of whitewashed interiors, whether in the stained-glass windows above or disguised as a common woman below. To be sure, many images of Mary were the target of Calvinist iconoclasts. But another art historian suggests that Reformation understandings of grace may have generated beautiful new paintings of the Virgin.

One of them is Pieter Aertsen’s Adoration of the Magi. The fact that the centre of the paintings is an empty hand of a king is not an accident, and it completely subverts traditional depictions of the gift-bearing royals. “Aertsen shows the magi is being blessed for his belief, not for his offering.” We come to God, as the Reformers so often pointed out, not to give but to receive. “We can respond to [gifts] as a live hand and try to clutch,” wrote Robert Farrar Capon, or we “can respond as a dead hand—in which case [we will] be perpetually open to all . . . goods.” Aertsen’s humbled, open, royal hand is the very essence of Christianity. “We can only receive contemplation’s gift,” insists Martin Laird; “ego knows only how to take.”

In the case of Luther, entire books have been penned elucidating a panoply of Lutheran images of Mary alongside Catholic ones. Luther’s last sermon took place in a pulpit bedecked with a beautiful image of Mary and her son. Luther’s love of Mary was lifelong, but how fascinating that all he really had to do to honour her in those final days was point above him. One scholar beautifully encapsulates the features of Luther’s Marian sensibilities (which I’ve touched on here before) in this way:

[Mary] revealed her gelassenheit, her “resignation” or self-surrender to God, as well as her “even mind” or equanimity in giving thanks to God no matter her condition. . . . This praise of Mary reveals Luther’s deep indebtedness to medieval mystical theology, for he presents Mary as the ideal mystic, one who lives “in pure surrender and obedience to the eternal Good, in love that frees.”

Moreover, for Luther, Mary preserves us from the considerable risks of mysticism. She is a safeguard against the mysticism that either forgets grace by carving our own private path to God or neglects the importance of the physical body. If this meritless surrender, this gelassenheit that results in Christ’s birth within, is what we learn from Mary, then what she offers is priceless: the pearl without price, in fact.

My aim is to playfully outdo Catholic and Orthodox Christians in my love for the Virgin. May the result of my praise be Orthodox and Catholic umbrage so that they respond to this Anglican’s affront with even more love for the Virgin.

I do not cite these Protestant sources because I require them, as if I need my apparel branded by an approved designer. It is instead to respond to those who suggest that Protestants have not loved the Virgin or that we don’t love her today. Indeed, by seeing Mary as the chief exemplar of justification by faith, Luther was only echoing Augustine:

When you look with wonder on what happened to Mary, you must imitate her in the depths of your own souls. Whoever believes with all his heart and is “justified by faith” (Rom. 5:1), he has conceived Christ in the womb.

It is hard to imagine a line more suitable to Protestant sensibilities, indeed to sensibilities that should characterize all well-formed Christians. If there is “one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all,” as Paul says in Ephesians 4, then there is one mother as well, the church, Mary the Virgin. In fact, Mary perfectly encapsulates what Protestant Christianity (or any Christianity) requires if it is to thicken itself enough to survive.

So no, there will be no giving up on Mary anytime soon, and with Advent upon us, I have just a few weeks to convince as many people as possible lest she be forgotten. My aim is to render out of date Jaroslav Pelikan’s clever quip about Protestants and Mary: “Most generations shall call me blessed.” Put more boldly, my aim is to playfully outdo Catholic and Orthodox Christians in my love for the Virgin. May the result of my praise be Orthodox and Catholic umbrage so that they respond to this Anglican’s affront with even more love for the Virgin. The net result—because envy does not befit believers—will just be more love. We are one church anyway (Ephesians 4 outranks church history), so this is friendly competition; our mother won’t begrudge our spurring one another on.

More Midwestern Madonnas

But I’m afraid I’ve had something of a head start. In terms of Mary, this was, as the birders call it, a big year for me. Not only that, but I deliberately timed this series to appear at the end of the year so that it will be difficult to outdo me before December 31. I’ve visited enough local Midwestern Madonnas to recast an earlier article on the Marys of my home region with entirely new examples. I noticed how Picasso’s elusive 1967 sculpture in Daley Plaza becomes a Mary at this time of year thanks to her being surrounded by the smell of mulled wine and the sight of wood-carved Nativity sets from Bethlehem at the Christkindlmarket. The atmosphere is sufficient to transform Miró’s Chicago sculpture just across the street into the crowned Queen of Heaven as well. Another of Chicago’s most beautiful Marys is at a downtown chapel of DePaul University. Immediately after Vatican II she was deliberately concealed behind a retractable curtain (a sad but fitting illustration of Catholic devotional decline), but I am glad to report that after this brief season of embarrassment the curtains are mostly open today. Still, if that is too concealed and intimate, Our Lady of the New Millennium—who made her tour of Chicagoland before finding her resting place at the Shrine of Christ’s Passion in Indiana—is no less than thirty-three feet tall. The website promises that “this serene, stainless steel four-ton beauty will inspire you.” But before we crack our Queen Kong jokes, realize that Mary was often depicted large by design. She carries so much symbolic freight that Jan van Eyck can barely fit her in a Gothic nave. Maybe our problem, as Charlene Spretnak argues, is that our Mary is too small. Our Lady of the New Millennium, moreover, is large in ways that exceeds mere size. The videos running at the Shrine have happily given up on tribal polemics, instead featuring Protestant pastors and Catholic priests sharing the ways this sprawling highway chapel (despite being a cataclysm of kitsch) transforms travelling souls today.

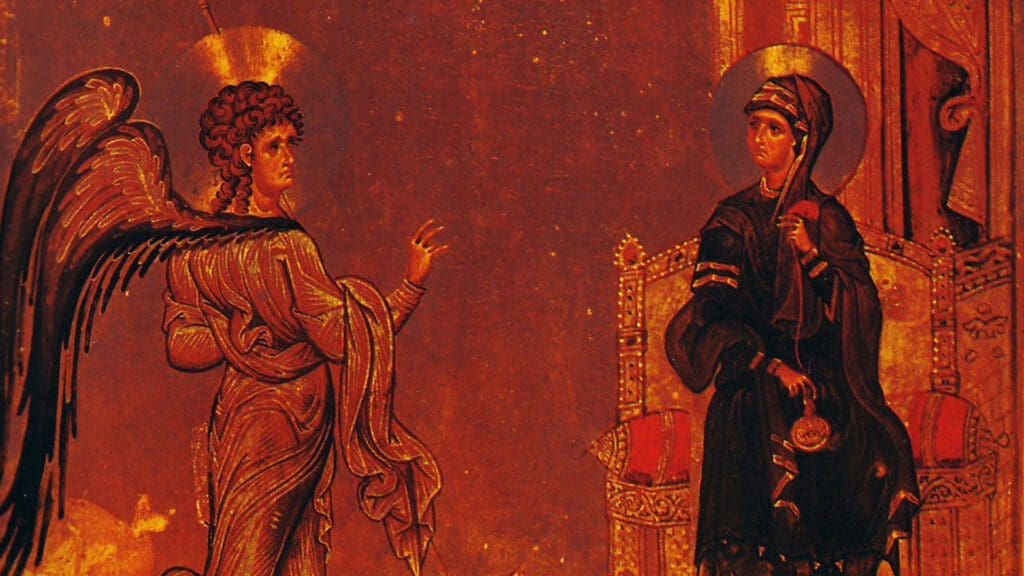

I also ventured to a nearby Orthodox monastery in Wisconsin known for its Marian devotion, and for its production of countless affordable icons (with which I’ve enhanced my classroom). I was most entranced by this monastery’s copy of the famous Kursk Root Icon. A medieval hunter discovered this Mary appended to the root of a tree in Russia, and a spring gushed up on the spot. When on the same trip I saw a beautifully carved root at a tackle shop, I knew (as you no doubt already intuited) what this chance discovery signified: the land of Wisconsin, also teeming with sacred springs, is holy as well. And what better way to express that holiness than with objects collected from the entire continent—a poor man’s mosaic made of shells, coral, copper, glass, and starfish—that lovingly encrust that most quirky of Wisconsin’s many Marian shrines, the artificial cave known as the Dickeyville Grotto. Don’t be put off by the patriotic accoutrements; that’s just how German immigrants convinced Wisconsinites they were good Americans, not secret agents for the kaiser or the pope. Wisconsin: come for the cheese, beer, and football; stay for Holy Hill and Guadalupe and Our Lady of Champion—for the state is one massive Marian shrine.

But can love ever be satisfied with the local? No, I aim to go further—much further. Everyone knows one must travel far to experience the Virgin, to refresh those conventional feelings grown stale by home routines. So this year I went on a Marian pilgrimage to India, to the greatest Indian Marian site in fact, Velankanni; then I discovered a nearly forgotten replica of Loreto (a famous Italian shrine) in that most Marian of North American capitals, Quebec City; and I went to the most important Marian shrine in London, where I found an ideal image of church unity, Our Lady of Willesden: not all Black Madonnas, it turns out, are in Poland, Spain, or France.

Again, Mary represents the church, which is why Orthodoxy’s Pokrov icon and its Catholic analogue, the Virgin of Mercy, not to mention the Protestant version, show her sheltering us all. So it was with my Marian pilgrimages this year. Collectively, the Marys I visited represent the universal church, from mild Midwesterners to the Christians (and many eavesdropping Hindus) of India, to Indigenous North American believers (the Huron and Haudenosaunee), all the way to those of British descent like me. I will share them all with you through these four weeks of Advent for a simple reason: so that you surpass me in the year to come with your own pilgrimages, pilgrimages so meaningful that, when I hear of them, I will look on this series with embarrassment and happily concede total defeat. For when you love Mary—and the son she unfailingly points us to—even more than I do, all of us win.

Our next stop is India. I hope to see you in one week.