V

This is the second in a four-part Advent series that explores Marian devotion at pilgrimage sites around the world. Part one is here.

Velankanni, the Lourdes of the East

Even if I did not walk barefoot to Velankanni, India’s great seaside Marian shrine, as many Indians do, I still endured considerable risk. As we made our way by car from Tiruchirappalli to the Indian Ocean, my driver shared his favourite YouTube videos with me. Not that I would have minded, except that he was watching them too. As we hurtled along the pilgrim’s path that parallels both village streets and a major highway, I urged his eyes to the road as politely as I could. When it rained, he sped up, appearing to relish the thrill of hydroplaning. As our vehicle pressed through the main street of one village, the crowds were so thick that we routinely bumped pedestrians. They gave the car a swift bang with their hand, which seemed more of a courtesy than a complaint. At the centre of this riotous crowd was a man with a steel bar driven through his cheeks. The bar, supported by his hands after it exited his flesh, was so long that it seemed to cover much of the road—an entirely new level of devotional exhibitionism to a Hindu deity I was unable to identify. But that crowd was headed to a Hindu shrine, and our direction was the opposite: the road to the Mother of God.

I asked my driver what happens if he hits one of the many cows, oxen, or goats sprawled along the main highway. “You keep driving, or you pay,” he replied, “so I keep driving.” When I dutifully collected my trash from the journey to place in a proper receptacle, he looked at me with disbelief and gestured for me to throw it out the window, saying—with a winning smile—“It’s India!” Even so, India’s colour and charisma leaves a far deeper impression than the trash. As we approached Velankanni’s sanctum, the welcoming signs advertising lodging, meals, and tonsuring stations (opportunities to shave one’s head) intensified. We arrived safely. When he dropped me off at the site, it was me and a sprawling campus of white shrines and statues, many of them reconstructed since the flood. And what a flood it was.

Many have read David Bentley Hart’s The Doors of the Sea, itself a response to bad Christian responses to the 2004 tsunami that struck on a Sunday, the second day of Christmas. What fewer realize is that the tsunami annihilated pilgrims visiting the statue of Our Lady of Good Health at Velankanni. Think about this for a moment: As pilgrims were showing their Christmastide devotion, the tides swallowed them whole. If they had stayed home, they would have lived. The waters rose to kill, in Hart’s words, “without thought or purpose or mercy.” Admittedly, the waters did not enter the shrine proper, which is on a higher plane, but this is small consolation. The pitiless sea swept away all on the beach and even those who gathered on rooftops to try to save themselves. Those who made it through the first oceanic onslaught were not spared. As the great wave receded, more victims—thinking they had escaped the worst—were sucked out to sea. In what must have seemed like a sickening boast, the ocean then regurgitated some of its dead on the shoreline. “Our shrine has suddenly turned out to be a burial ground,” lamented the rector who worked to recover hundreds of Velankanni’s bodies.

The BBC interviewed a woman who lost her baby boy in the water: “When the tsunami hit I ran to the church and begged for the life of my son,” she said, crying. “All I got was his dead body. God cheated me.” But this cry is itself a Marian one. The same article’s implication that somehow suffering invalidates Christianity is shallow—as shallow as the waters that swallowed these victims were deep. “Perhaps we [Christians] did not notice the Black Death,” writes Hart, “the Great War, the Holocaust, or every instance of famine, pestilence, flood, fire, or earthquake in the whole of the human past.” And most poignant is Hart’s refutation of facile appeals to providence: “When I see the death of a child I do not see the face of God, but the face of his enemy.” If Mary represents the depths of the church, the church at the source, as Joseph Ratzinger and Hans Urs von Balthasar have argued, then in a way Mary was with those who perished, each one of them a sea-soaked Calvary where she lost a precious child again.

Moreover, if it is true that at the resurrection the sea will give up its dead (Revelation 20:13), then we can read Hart’s tsunami theodicy in a Marian mode: “There is in all things of earth a hidden glory waiting to be revealed, more radiant than a million suns, more beautiful than the most generous imagination or most ardent desire can now conceive.” Advent is the season of waiting, the season of judgment, the season of pregnancy. This applies not only to Mary’s swollen womb during the first coming of Christ but also to the cosmic pregnancy of the second as well, when “the earth will give birth to her dead” (Isaiah 26:19). Indeed, considering the resilience of this faith in the love stronger than death (Song of Solomon 8:6; 1 Corinthians 15:55), it is no wonder that the shrine of Velankanni, nearly twenty years after the tsunami, is thriving again.

On the face of it, an observer might see the barefoot throngs of pilgrims, or the back-to-back beautifully emblazoned buses (North American vehicles, by the way, are incurably boring), to be just one more manifestation of Hinduism. After a bath in the sea and an optional head shave, pilgrims to Velankanni purchase an offering of coconuts, bananas, flowers, incense, or a mix and bring these gifts to the shrine. Is this not worship of nearby Hindu mother goddesses in another form? Actually, it is not. At Velankanni I saw no one with iron bars bored through their cheeks, owing to the nails that pierced Christ’s hands instead, nails that the site’s ubiquitous crucifixes won’t let anyone forget. Indeed, one anthropologist who assumed Velankanni to be just another form of Hinduism—after hearing repeatedly from pilgrims that there was a difference between the Hindu mother goddesses and the Virgin—finally conceded. “Some differences did start to register with me,” he admits. And these differences, it turns out, make all the difference. If the tsunami had hit another seaside shrine, the shrine to Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity, in Chennai, or any shrine to Mariamman, the Hindu goddess of weather, the goddesses would have a lot to answer for. But the human Mary, after all, is the Mother of Sorrows herself.

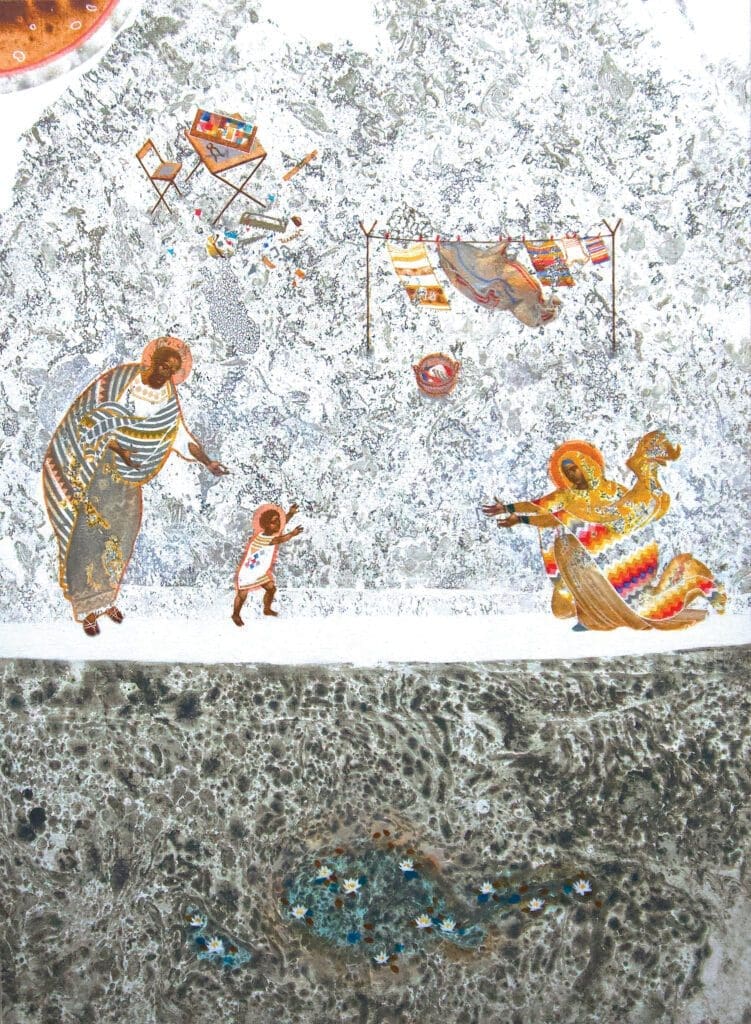

If Lourdes is the great Marian healing shrine of the West, Velankanni is that of the East. It hosts millions of annual visitors, mostly landless laborers who work the area’s rice paddies along the Kaveri River plane. On Velankanni’s September feast day, the population of the town temporarily swells to over a million at once. As at Lourdes, there have been so many healings here that a museum displaying discarded medical paraphernalia was created on site. Before the healings began, Velankanni was first hallowed as the site where Mary appeared to Hindu children. One of these stories features a shepherd boy whom we might call the Indian Juan Diego. While delivering milk, he stopped to rest under a banyan tree by a water tank. He saw a vision of Mary and Jesus, and Mary asked him for some milk. He hesitated, wondering how he would account for the deficit, but gave her some anyway. When he arrived to make the delivery, his milk pot was filled again.

Mary, after all, is the Mother of Sorrows herself.

Another story connected to the site is of a lame boy with buttermilk who offered some to a mysterious woman with her son. The woman turned out to be the Virgin, and the boy was healed. Spare me, please, any quibbles about the “historicity” of these accounts. In addition to the possibility that these events did in fact happen, the tales function as magnificent parables of generosity. “For all things come from you,” as the Anglican liturgy puts it, “and of your own have we given you” (1 Chronicles 29:14).

Velankanni, however, is not only for Indians. In another story connected to the site, Portuguese sailors were rescued from shipwreck by Mary, and afterward they offered Chinese porcelain plates in gratitude, which enhance the wall behind her statue to this day.

As to whether Christ is sufficiently honoured at the shrine, the outdoor statue of Jesus that is far larger than the shrine’s main statue of Mary, along with the Frisbee-sized Eucharist set up for adoration in a packed nearby hall, should settle that misunderstanding. In her wonderful meditation on how Indian thought can inform Christianity, the Catholic nun Sara Grant proudly reports of one Hindu sadhu who wandered much of India, spending time in many ashrams. But after meditating in front of the Eucharist at Grant’s Christian ashram in Pune, the sadhu reported a quality of presence that he had detected nowhere else. So it is at Velankanni today.

But Velankanni is not just for the pious. The combination of souvenir stalls and confections reminded me as much of the New Jersey boardwalk as a venerable religious locale. When, after forgoing the head shave, I found my way to the central shrine itself, I came with a certain level of expectancy. After three weeks in India I had heard many speak of the “vibes” in given places, the stupa at Sarnath or the main room at the Ramana Maharshi ashram. I had visited both places but found the vibes (if we insist on using the term) at Velankanni to be of a considerably higher grade. “You are here to kneel / Where prayer has been valid,” wrote T.S. Eliot. This is a place where prayer has been valid. But lest you think this is just my Western Christian bias betraying itself, please read on.

Interlude at the Diamond Throne

Just two weeks before, I had visited the Bodhi Tree at Bodh Gaya, the most famous of Buddhist pilgrimage sites. The tree, under which the Buddha himself was enlightened, is surrounded by temples representing every known form of Buddhism, but also by the worst poverty I have ever witnessed. Peaceful images of meditating supplicants were therefore offset by locals defecating in the street. There is no question I also sensed something powerful at what is known as the Vajrasana, the “Diamond Throne”—that is, the ancient stone slab where the Buddha meditated, which now sits under what (pilgrims are told) is the distant arboreal progeny of the original tree. But, on my visit at least, there was a fish carcass discarded next to the Diamond Throne as well. Henri de Lubac famously said that were it not for the incarnation, made possible, of course, by Mary, then Buddhism would be the greatest spiritual fact in history. Goaded by this challenge, I had been studying it for years. My shelves were swollen with books about Buddhism, not only its history and theory but its practice as well. I had even taken the step to find a formal Zen teacher who accepted me as Christian student, and a trip to Kyoto was in the works. Which is to say, I had been preparing for this about as much as a Christian can.

Behind the Bodhi Tree is a massive structure known as the Mahabodhi Temple. I met one of the town’s few Christians, and he informed me that the monks meet at five in the morning to meditate. And so, after fighting off some aggressive street dogs (making myself appear large with an umbrella was effective), I sat and meditated with Buddhist monks from all over the world. The Buddha may have sat still here for seven weeks, but I was proud of myself for clocking just under an hour. I cannot deny that something happened to me as I sat before the statue of the Buddha, whom the monks lovingly dressed in yellow robes. You might call it an unexpected confidence, a curious sense, emerging from the mud of my distracted soul like the bloom of a lotus, that maybe it really didn’t matter what others thought of me. I’d stop far short of calling it enlightenment, but the confidence was almost frightening, perhaps even dangerous.

What better place to test this insight than at a Christian-Buddhist ashram deep in India’s verdant hills, the ideal place—I was told—for Christians who wished to take Buddhism seriously as well. When I arrived at the centre, a spartan but spacious Bauhaus residence ensconced in green mountains, I booked a meeting, known as dokusan, with one of the Zen masters. I told him about this unexpected confidence I had experienced at the Bodhi Tree. His response staggered me: “You have every reason to be confident if you are a Christian. Some here may tell you that your Christian faith is ‘dualistic.’ Don’t believe them. That charge applies to Manichaeism, but not to your faith.” It turns out this Zen master was also a Cistercian monk.

It also turns out this warning was needed. Indeed, I did encounter people at this meditation centre who displayed a shallow understanding of Christian faith. Some of my fellow retreatants had read deeply in Buddhism, but they had stopped their reading of Christianity with debunkers like Bart Ehrman. As far as the depths of spirituality is concerned, this is to compare not apples and oranges but grand cru French grapes and an expired bag of Raisinets. Still, other retreatants seemed to be successfully treading both paths at once. Or did it only seem this way because, like Nicodemus, they were Buddhist in public while betraying their Christian faith to believers like me in private?

During my visit I underwent koan training. Koans are intentional paradoxes meant to defeat the rational mind. Koans are experiments in “unknowing,” an especially suitable tonic for minds formed in the post-Enlightenment West. But did I not already have such koans in the parables of Christ? “Stop the sound of the distant temple bell” was the quandary that was posed to me. Over multiple sessions, a different Zen master and I concluded that it was an impossible request. One cannot un-ring a bell. Instead, one can only surrender to it. If whispered words can be urgent, these words so softly spoken to me certainly were: “Matthew, there is only the sound.” It was said with disarming kindness, finally enabling me to decipher the koan’s depth. Once I got over the fact that, amid nearly forty retreatants, this man actually remembered my name, I could feel myself ringing.

Still, the place felt publicly more Buddhist than Christian. And for all the limitations of reason, had God not created the rational mind as well? The church service that happened on Sunday in the same centre was very sparsely attended compared to the Buddhist meditation sessions, but it was intimate and lovely. I dutifully read the justifications for such hybridity in the literature on offer at the site but found the claims less than convincing. Before I left, I received one more warning from the first Zen master I had met, the one who was also a Christian monk: “There is much more theological and philosophical work that remains to be done here,” he told me, almost wearily.

The conflicting instructions left me unsettled. Perhaps I would continue this kind of Zen training, allowing Zen to bring out dormant dimensions of Christianity. But I didn’t know. Thanks to the evangelical tradition, the words of Scripture were embedded deep within me: “If the bugle gives an indistinct sound, who will get ready for battle?” (1 Corinthians 14:8). Such is the puzzlement I brought with me to the shrine of Our Lady of Good Health at Velankanni. It was time to go inside.

At the Shrine

I threw my American footwear into a large pile of sandals and shoes outside the shrine. Sadly, what I paid for those off-brand sneakers easily exceeded the value of all the footwear in sight. I stepped inside and moved toward the statue alongside hundreds of Indian supplicants. I sat there as I had under the Bodhi Tree. But at this shrine I did not have to meditate for an hour. Almost immediately—and if you read the following words with skepticism, I assure you I would read them that way as well—I heard Mary speak to me. Or was it the Holy Spirit? Or both? Three simple words, plainly delivered as practical instructions. They were said with an authority that I would not think to question; but they were also said with love. “Give up Zen.” I have on other occasions agonized many hours over whether what I heard within me was the voice of God. (For goodness’ sake, I was once part of a Vineyard church plant.) But this time no agonizing was necessary. I knew what I heard. The instructions transcended rational analysis, let alone psychoanalysis, and unlike any mysterious koan, I knew exactly what they meant.

There in India I found Mary, mother of the church, keeping me inside it.

Mary’s words, her very few words, solidified my attachment to the church, and to Christ. If my life is any barometer, Mary doesn’t take to speaking out loud to her children too often. But she did this time, for I needed it. So there in India I found Mary, mother of the church, keeping me inside it. Mothers know what to say to their children, don’t they? I recommend you make your way to Velankanni and find out what Mary has to say to you.

On the other hand, you need not go anywhere at all. Instead, we can all relish the fact that we Christians—we sons and daughters of Mary—are already home. We are already in the household of our heavenly Father—“my Father and your Father,” as Jesus said (John 20:17). I may have begun this series with a warning against being excessively competitive about Mary, but rivalry can sometimes be fitting. Zen has its limits. Mindfulness alone cannot account for the dead children of Velankanni; instead, to again quote David Bentley Hart, this “requires a labor of vision that only a faith in Easter can sustain.” I am grateful for how Buddhism can stir Christianity’s contemplative enzymes. But this also is true: Velankanni’s three jagged pinnacles are preferable to those of the Mahabodhi Temple. The Throne of Wisdom (which is Mary herself) is harder than the Diamond Throne. The wood of Calvary is more precious than that of the Bodhi Tree, the sepulcher surpasses the stupa, and Jesus outranks the Buddha (and the Buddha, who I think may have predicted the Nativity, knows as much).

Or, if an urgently whispered koan is more to your liking: There is only the Christ.