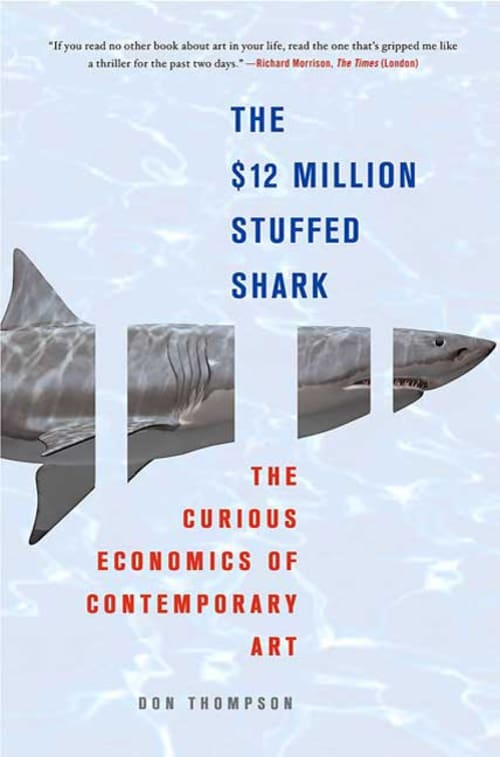

The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art by Don Thompson. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. 272pp.

I.

The media coverage surrounding British artist Damien Hirst’s recent presentation of over three hundred “dot” paintings (most of them painted by his assistants) at Larry Gagosian’s eleven galleries around the world, reminded me of my defense of his most infamous work, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) in the Summer 2010 issue of Comment. Commissioned by the British advertising executive and art collector Charles Saatchi, the fourteen-foot stuffed tiger shark suspended in a tank filled with formaldehyde was sold in 2005 to the American hedge fund executive Stephen Cohen for $12 million and recently donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This work embodies the mysterious opacity of the contemporary art world, which frustrates even the most culturally engaged Christians.

I wrote that Christians need a more robust understanding of the rich and complex habitus of the contemporary art world, consisting of the labyrinthine network of institutional and sociological fields that can make a stuffed shark a highly successful and valuable work of art. I argued that the cultural mandate—what Andy Crouch calls “the relentless, restless human effort to take the world as it’s given to us and make something else”—includes the messy and unsightly sausage-making that characterizes the means and mechanisms by which art makes its way from the studio to galleries and museums. I went further to suggest that with its holy days, liturgies, relics, and other practices that maintain belief, the art world operates like a religion. And that should command our interest, whether or not we like the stuffed shark and approve of the institutional framework that made it possible.

|

But there is a much darker side to the contemporary art world, which economist Don Thompson explores in The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art (Palgrave/ Macmillan, 2008). The book analyzes the mystifying economic structure that characterizes contemporary art at the highest echelons. For Thompson, this art world is characterized by insecurity. “Never underestimate,” states an auction house director, “how insecure buyers are about contemporary art, and how much they always need reassurance.” Insecurity is the fuel that powers the network of auction houses, galleries, museums, and interpretation, which serve as validating mechanisms, reinforcing decisions to acquire, represent, exhibit, or review an artist’s work. Thompson’s book suggests that this rarely has to do with the quality of the work of art itself, but the leverage of secondary indicators. “The value of art often has more to do with artist, dealer, or auction-house branding, and with collector ego, than it does with art.” But the collector’s ego is fragile. “Most of all,” Thompson writes, “they want reassurance that, when they hang the art their friends will not ridicule their purchase.” Whether it is $12 million for a stuffed shark or $200,000 for a canvas with oil paints smeared on it, collectors need to be confident that their purchase brings power, prestige, and cultural capital.

Artists at this elite level know this and develop their own strategies of enchantment to provide such reassurance. “The job of the artist,” Francis Bacon once said, “is always to deepen the mystery.” The strange personas and outrageous gestures of Andy Warhol, Joseph Beuys, Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, and Maurizio Cattelan are intentionally crafted efforts to enchant collectors, easing their insecurity. In an age when collectors and dealers regularly consult a website called Artfacts (www.artfacts.net), which ranks artists like stocks, rising and falling on a daily basis, such strategies are absolutely necessary.

The insecurity that haunts collectors and dealers also crushes artists, forcing them into a high-stakes game of behavioural poker, in which their very livelihoods and identities are determined by a small group of wealthy but unpredictable collectors pursuing entertainment and validation. To dismiss this as antithetical to the integrity of art over-idealizes it and distorts the social and institutional fabric from which the work emerges. Moreover, this situation is the same for a painter of landscapes as it is for Damien Hirst.

II.

For the Lutheran and Reformed traditions, the cultural mandate is the foundation upon which vocation is built, encouraging culture-making and faithful presence in contemporary culture. After the Fall, however, we must exercise this God-given responsibility and desire to cultivate the earth east of Eden, in Cain’s city of Enoch. Reformed theologian Michael Horton reminds us that creation operates within the covenant of law: “Law comes before gospel because creation comes before the Fall.” Culture thus bears the mark of Cain, the curse of toil and hardship. It is what is produced by our desperate wanderings, geographically and spiritually, and our greatest cultural monuments are often wrought through violence and death. Leo Tolstoy’s wife, Sofia, who sacrificed her life to serve her husband, wondered how many people would have to be consumed to enable the fire of genius to burn. It is impossible to read such masterworks as The Death of Ivan Ilych or Anna Karenina and not consider the pain and misery that the production of these works caused to the author’s friends and family, not to mention to the writer himself.

This is tragic because great works of culture, whether paintings, poems, or cathedrals, are embodiments of a God-given urge for eternal life. They are monuments to their maker’s existence, to their physical and emotional presence as image-bearers of God. They are a powerful and beautiful defiance of their mortality. Some of the best of these monuments may even be offered to the Unknown God, straining toward, even experiencing, an aesthetic intuition of God’s love. Crouch writes in Culture Making, “All our culture making must be bound up in this prayer—that what we make of the world will last after the world itself has been rolled up like a scroll.” This is as true of the non-Christian as it is for the Christian. Art indeed functions like a religion, but as religion, it is based on law. And it can crush.

The “curious economics of contemporary art” that Thompson explores is the result of the internalization of insecurity and unsatisfied desire—that is, law. Modern and contemporary art becomes what Reformed Pastor and author Tullian Tchividjian has poignantly and accurately called “self-salvation projects,” characterized by the efforts “to do more/try harder.”

Although Tchividjian’s primary target is the confusion of law and gospel in Evangelicalism that clouds grace, it offers significant secondary implications for modern and postmodern cultural analysis. Horton observes, “Although the goal of the law, according to Paul, is to silence the world before God, modernity is one long filibuster in which the sovereign self refuses to yield even to the Speaker of the House.” What are we to make of works of art produced by such a filibustering sovereign self, crushed by the law and kicking the goads, and for whom art is the only salvation, the only hope for eternal life? From this vantage point, there is much more at stake than simply the merits of the stuffed shark as a work of art and talking about “worldview.” (In fact, many Christian worldviews are as law-based as secular ones.)

III.

But the mark of Cain is not only a curse but a blessing. It reveals (common) grace. “Because of God’s common grace,” Horton observes, “no culture is entirely devoid of any sense of truth, justice, and beauty.” As Paul writes in Colossians, it is in Christ that “all things” hold together, even poems and paintings made by filibustering sovereign selves. Viewed through the lens of Christ, who says from the cross, “It is finished,” we can receive these works, wrought from fear and violence, as gospel and as grace, receive them as part of the liberating power that frees us to create and experience, to make and be shaped by culture, and be a faithful presence in a world in which Christ is working to make all things new, and in whom we have all we need.

Referring to the implications of justification through the finished work of Christ, Lutheran theologian Gerhard Forde asked, “What are you going to do now that you don’t have to do anything?” This is a freedom that can come only from beyond the hills (Psalm 121), a freedom no artist can manufacture, not even Damien Hirst.