T

This is the bright home

in which I live,

this is where

I ask

my friends

to come,

this is where I want

to love all the things

it has taken me so long

to learn to love.

This is the temple

of my adult aloneness

and I belong

to that aloneness

as I belong to my life.

There is no house

like the house of belonging.

—David Whyte, from “The House of Belonging”

The Boy with the Suitcase

When I was eleven years old, my parents kicked me out of our home. In some ways it was a mercy. Most of my life to that point had been lived under the shadow of a toxic marriage, untreated mental illness, corrosive verbal abuse, and degrading physical violence. As is their way, these things marked me indelibly—marked all of us—leaving wounds both physical and spiritual. But even so, it was my home. It was the place of my mother’s wonderful laughter. Of weeknight dinners and Saturday cartoons. Of my sister’s dance recitals. Of my own solitude. Though living in that home had wounded me in a thousand ways, leaving it was, perhaps, the greatest wound of all.

My remaining memories of that first home are fragmentary and impressionistic, blurred by childhood’s distance and trauma’s fog. Slamming doors. Angry silence. Shadowed doorways. Welted skin. There are good memories too: Wiffleball in the backyard. My baby sisters in their Easter best. Neighbourhood bike rides scented with autumn woodsmoke. But what I remember most is the moment when I was told to pack my suitcase and leave.

I had packed that suitcase many times before. For most of my eleven years, it was a weekend ritual. I would take it down, pack a few of my things, and wait for my dad to pick me up for our weekend visit. An hour later I would go to my room at his apartment and settle my clothes into his drawers. We spent the weekends together driving through the mountains, shelling garden beans on the porch of my grandmother’s house, and reading the cartoon section of the weekend paper in our pajamas. And then, two days later, my clothes and suitcase smelling of Marlboros, I would return home and unload it all again.

But this time it was different. This time the volatility, pain, and sickness that had, for years, built up inside our home finally ruptured, cutting me off from all that I knew and sending me into what felt like an abyss. This time when my dad picked me up, I was leaving my home forever.

The reasons for this rupture are no longer important. The time to isolate causes or assign blame has long since passed, and it’s just as well. My family knows what happened, and we have—for the most part—forgiven one another and forgiven ourselves. Even so, one of the harder lessons I’ve had to learn is that understanding the cause of something is not the same as escaping its effect. We can grasp the reasons for our wounds, but we cannot elude the wounds themselves. For me, the fresh wound of that Saturday morning so many years ago was an inescapable sense of being unwelcome, a sense of being so flawed as to warrant only loveless exile, a tormented form of existential homelessness so profound, so vulnerable, so desperate, as to be almost pathetic.

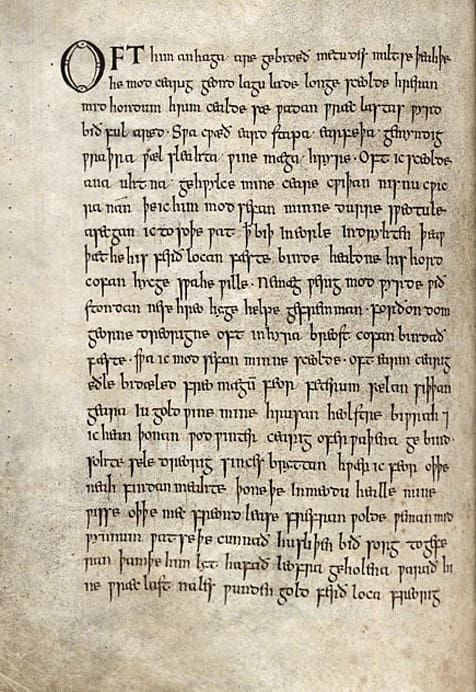

Not long after I left that first home, I came across an old Anglo-Saxon poem called The Wanderer. It tells the story of a warrior who has lost his liege lord, his companions, and the fortress hall they shared. Having buried these friends, he is condemned to make his way across frozen, stone-coloured seas in search of a new home. It was the first time a poem gave me language for my experience. I, too, felt like I was friendless and alone, driven by hidden currents of wind and ice away from any shore of belonging. I wrote some of my favourite lines in my spiral notebook.

I hid my lord

in the darkness of the earth,

and I, wretched, from there

traveled most sorrowfully

over the frozen waves,

sought, sad at the lack of a hall

a giver of treasure,

where I, far or near,

might find

one in the mead hall who

knew my people,

or wished to console

the friendless one, me.

Though I was only twelve years old when I read these words, I instantly recognized the search and its longing for consolation. And oh, how it drove me. Over the course of the next decade, I followed the currents of that longing into all manner of places, searching every horizon for some space, some embrace, that could give me reprieve—however momentary—from the experience of unwelcome.

I remember once sitting at a red light in the back seat of my parents’ car. I looked over at the car beside me and saw a girl my age. We stared at one another for a moment, her face kind and open, and she waved at me. Electrified by the experience of recognition, I waved back as we held one another’s gaze. Moments later I craned my neck to hold on to her image as the light changed and she moved away.

It’s a childish moment, to be sure, but it is as clear an image as any of the way I made my way through the world. Closeted in my own solitude, yet always scanning a nearby face for a glimmer of recognition, I would become enflamed when it came and heartbroken as it faded away. I found temporary shelter in sex, food, distraction, secrecy, enmeshed relationships, the wilds of my imagination, and dramatic swings of identity. “I’m a breakdancer! No, I’m a politician! No, I’m a basketball player! No, I’m Scottish!” But in spite of all of this, I never felt fully at home. No matter where or what I was or who I was with, in some hidden place the boy with the suitcase remained.

The Realm of Hungry Ghosts

In ways that I never could have anticipated, this wound prepared me for the life I would come to live. I spent some of my first years after college working at a mission in St. Louis, teaching in a men’s long-term residential program by day and supporting its homeless shelter at night. My sixteen years in parish ministry were largely devoted to helping people negotiate their own chronic experiences of spiritual and relational homelessness, and to offering them nourishment along the way. The first fifteen years of my life as a scholar were largely focused on modernity—an era of history defined by a series of concussive displacements and consequent alienation—and on the possibility of creating a humane life in the dazzling wilderness it made. My life as a writer is devoted to creating narrative spaces in which people can find both themselves and one another and so remember that, in spite of what our fears tell us, none of us is ever really alone. My current work as the creative director of the National Memorial to the Underground Railroad leads me to engage daily with a social movement that had fugitivity and the search for welcome at its heart.

In recent years, and for reasons that I have partially described elsewhere, my attention has settled on a very particular form of homelessness; a form that—perhaps more than any other—is critical for understanding our time. I am speaking here not of the physical homelessness caused by economic inequality, the spiritual homelessness caused by a fallen world, or the intellectual homelessness caused by modernity—as powerful as each of these remain. I am speaking of the emotional homelessness caused by trauma.

Suddenly everyone I knew was talking about their bodies keeping the score, and we were all reinterpreting our lives through the lens of trauma.

Up until about ten years ago, the language of trauma was, for me, largely identified with crime shows—“blunt force trauma with a crowbar” and so on. At some point, though, I began to hear this language used in a different way—less as an injury to the body and more as an injury to the mind, the heart, and the soul. I first heard it from my therapist who began to talk to me about complex post-traumatic stress disorder. But I also heard it from my friends who heard it from their therapists. I heard it from writers like Curt Thompson (no relation), Judith Herman, and the ubiquitous Bessel van der Kolk. Suddenly everyone I knew was talking about their bodies keeping the score, and we were all reinterpreting our lives through the lens of trauma. To my surprise, I found that in spite of the relative newness of this language, I was immediately fluent. I could, it seemed, intuitively conjugate its forms. And I found that this language, in a way that no other discourse had, gave me the tools to interpret both the external and the internal realities of my life in a new, truer way.

I suspect there is no shortage of cranks out there who view the advent of trauma discourse with a wary eye. Many of a certain generation (and sometimes gender) see it as little more than the latest gnostic iteration of the therapeutic self-absorption of a culture already predisposed to luxuriate in its own victimization. I myself have been surprised by both the speed and the ubiquity of trauma’s discursive ascendance. And I have my own concerns about the way the language of trauma—language rooted in the depth of human pain and the power of extraordinary research—can be flattened and commodified by trauma influencers hawking mushroom gummies and bath salts.

Even so, while trauma categories can be dulled by overuse, my sense is that we are still a long way from that point. In my view, we are not talking about trauma enough. For as pervasive as the language of trauma has become, the experience of trauma is more pervasive still.

The picture that trauma theorists paint of our world is heartbreaking. It is a world of children, born at once deserving love and in desperate, unfulfilled need of it. It is a world in which those children—for reasons beyond their control and understanding—are wounded by others, scarred by shame, and displaced from the safety of love. It is a world in which those children, using the spare tools within their reach, create all manner of strategies for finding love and avoiding pain. It is a world in which, over time, those children become adults, bringing—without even being aware of it—their childish strategies for self-protection with them. It is a world in which those strategies eventually calcify into weapons of infantilizing harm, deepening the wounds they were designed to protect. It is a world in which, because of this misguided self-protection, the originating wounds of childhood re-emerge with strength and metastasize with speed, compromising our nervous systems, corrupting our relationships, and corroding our hopes. It is a world in which—without direct and deliberate support—these wounded children continue to live on, trapped in aging bodies until at last, to one degree or another, their wounds finally consume them. And it is, to a degree that many of us would scarcely believe, the world of many, many of those around us.

This point bears elaboration. The formal study of “trauma” as a category for interpreting human behaviour emerged in the years following World War I. Hundreds of returning soldiers, with no evident physical injuries, nonetheless exhibited a host of debilitating physical symptoms: headaches, memory loss, tinnitus, blindness, muteness, dissociation, uncontrollable bodily tics. Physicians, while initially nonplussed by—indeed, suspicious of—these symptoms, eventually (thanks in no small part to the recent work of Sigmund Freud) understood that what they were witnessing was the result of some form of psychological injury. And while they had limited understanding of both the causes and the effects of this injury, a new field of inquiry was born.

We are, I see now, simply so many little boys and girls with suitcases in search of home.

Over the next fifty years, the study of trauma was almost exclusively focused on veterans of combat, eventually culminating in the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a critical diagnostic framework. Over time, however, researchers working in non-military contexts began to observe these same symptoms in their client populations. Judith Herman, for example, saw strong evidence of PTSD in her work with survivors of rape, incest, and domestic abuse. After years of interviews with both war veterans and sexual assault survivors, she published her groundbreaking book, Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Her work demonstrated that trauma was not merely the result of war but of violence broadly conceived. That trauma was, in fact, the result of any situation in which an individual—in the face of overwhelming power—loses a sense of personal autonomy or bodily safety. And while, as a matter of course, both the sources and the symptoms of trauma vary in their intensity, the underlying dynamics of trauma remain in place.

As van der Kolk puts it in his bestselling book, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, “One does not have to be a combat soldier or to visit a refugee camp in Syria or the Congo to encounter trauma. Trauma happens to us, our friends, our families, and our neighbors.” What the history of trauma research shows, in other words, is that trauma is not best understood as the tragic experience of a limited and extraordinary few, but as a fundamental aspect of countless ordinary lives. We live, as the Canadian physician Gabor Mate once put it in his work on trauma and addiction, “in the realm of hungry ghosts.”

I once saw a photograph that depicts this world perfectly. It shows a group of English schoolchildren during World War II, fleeing the bombing of their homes. As they emerge from the train station, they carry suitcases in their hands and wear tags around their necks. They are looking for a home. And they do so in the hope that somewhere, someone is also looking for them. This is the picture of the world painted by trauma theorists. Theirs is a critical corrective to the reductively pathologizing paradigms—long regnant in theology and psychology alike—for interpreting our collective homelessness. Because of this, it is my earnest hope that all of us—as people, as neighbours, and as practitioners—will devote ourselves to the work of understanding our emotional homelessness, and to squarely facing the traumas from which it comes.

Come Be with Us

As I have given myself to the work of understanding the trauma in my life and in the lives of those around me, I have found a surprising capacity to view both myself and others through new eyes of clarity and compassion. We are, I see now, simply so many little boys and girls with suitcases in search of home. And I have come to see something of the deliberate and ongoing work that it takes to heal from that trauma. A willed habitation of one’s body. Awareness of one’s emotions. Familiarity with one’s wounds. Honesty about one’s defences. Daily, hourly, re-anchoring in the real world, the world outside our fears.

The practices that sustain this work are many: breathing, meditation, prayer, pausing, walking; grounding through sight, smell, and touch; and ongoing therapeutic exploration of the fragments of trauma lodged in the mind. But one of the most powerful and surprising (to me) practices for the healing of trauma is the practice of hospitality. I’m not sure why this surprised me. After all, if the wound of trauma is the wound of exile, it makes sense that its healing comes through embrace. The slamming of doors undone by their opening. The angry silence broken by the gentle sound of one’s own name. The placeless architecture of a fearful mind replaced by familiar spaces in which we can find assurance and rest.

If the wound of trauma is the wound of exile, it makes sense that its healing comes through embrace.

But it did surprise me. After years of hiding my wounds behind solitude and secrecy, the prospect of bringing the fullness of my pain into the bright presence of a welcoming other was one I wished desperately to avoid. But it was also a prospect I wished desperately to embrace. Because somewhere in there, in spite of my endless evasions, this is exactly what I longed for. It is what we all long for.

This was one of the original insights of psychotherapy: that the invitation to be present with another and to unearth pain in their presence was itself constitutive of healing. As Herman shows in her work with sexual assault survivors and war veterans, it was the innovative practice of group-based therapy that saw—and continues to see—some of the most powerful and sustained examples of healing. In Trauma and Recovery, she puts it this way:

Traumatic events destroy the sustaining bonds between individual and community. Those who have survived learn that their sense of self, of worth, of humanity, depends upon a feeling of connection with others. The solidarity of a group provides the strongest protection against terror and despair, and the strongest antidote to traumatic experience. Trauma isolates; the group re-creates a sense of belonging. Trauma shames and stigmatizes; the group bears witness and affirms. Trauma degrades the victim; the group exalts her. Trauma dehumanizes the victim; the group restores her humanity. Repeatedly in the testimony of survivors there comes a moment when a sense of connection is restored by another person’s unaffected display of generosity. Something in herself that the victim believes to be irretrievably destroyed—faith, decency, courage—is reawakened by an example of common altruism. Mirrored in the actions of others, the survivor recognizes and reclaims a lost part of herself. At that moment, the survivor begins to rejoin the human commonality.

To centre hospitality in this way is not to diminish the importance of other forms of trauma healing. Hospitality is the context for—not a replacement of—these things. Hospitality provides the one thing that nothing else can: the presence of the welcoming other as the essential context for becoming whole.

One of the most extraordinary expressions of this insight can be found on a farm about an hour outside Nashville, Tennessee. This is one of two locations for Onsite, a globally recognized centre focused on trauma, healing, and emotional wellness. They offer individual therapy, group therapy, equine therapy, outdoor experiences, and varieties of classes taught by expert clinicians who have themselves walked the path of healing. And they offer these things in programs that range in length from a long weekend to months on end. But at the heart of it all is a foundational commitment to the role of hospitality in the healing of the human heart. In an interview from August 2020, Miles Adcox, the CEO of Onsite, put it this way:

There is often just as much healing in the hospitality effort as there is in any therapeutic modality. So, we really lean heavy on what we call healing hospitality. I’m grateful to get to work with some of the world’s best therapists. But often it’s the cook or the culinary professional that changes somebody’s world, just by how they treat them, how they connect with them. That’s intentional. Often, our drivers, for example, are a big part of our therapeutic effort because they know how to hold space for people when they’re coming into that ambiguity and they’re a little bit fearful and they know how to be a good presence for them. I think it was a love of hospitality that made me want to be a part of making the door wider for people to walk into painful parts of their story, and be intentional about setting up other places that would help people do that.

I have, in my own life, experienced the truthfulness of Miles’s words. During one of the worst times in my life, a friend and Onsite alumnus recommended that I go there and connected me with Miles so that I might explore that possibility. Miles called me one winter night, and I walked through the darkened streets of our neighbourhood as we talked. After telling him some of my past story and my current circumstance, he said very simply, “I hope you will come and be with us. We have a place for you here where you can rest.”

A week later, I walked out of the Nashville airport and was greeted by David, one of the drivers. As I slid into the back seat, I wondered what I had just done and dreaded what I was about to do. But David, having been down this road before, simply offered me some water, told me it was going to be okay, and gave me permission to rest. And that is exactly what I did. My days at Onsite were full: medical exams, meetings with individual therapists, sessions of group therapy, lectures on trauma and its effect, and late-night conversations with new friends. But every moment was rooted in the ethos and habits of hospitality, a commitment to the practices of belonging and to their transforming effect. This commitment could be seen in the room where I slept: quiet, well-lit, sanctuaried. It could be seen in the spaces where I met with therapists: warm, spacious, humane in scale. It could be seen in the beauty of the grounds: trails to wander, benches to rest, porches to linger. And it could be seen in the dining hall, a beautiful Scandinavian-style barn structure with wells of light, long tables, and nourishing food. My new friends and I spent hours at those tables, processing our sessions, refilling one another’s glasses, and sharing desserts. When the weather was nice we would sit under the peaked roof of the porch, enjoying precious moments of safe silence in the afternoon light. Miles had told the truth. There was a place for me there. And, for the first time in years, perhaps in my life, I began to heal.

A Stool in the Kitchen

One of the benefits of my time at Onsite is that it enabled me to view my life through a lens of hospitality rather than just homelessness. In ways that I never could have imagined, the welcome I received there unlocked an awareness that, as much as my life has been marked by exclusion, it has been just as truly marked by the reality of embrace.

One of my earliest and most enduring experiences of welcome came during those weekends away with my dad. Every Saturday, without fail, Bruce—as I always called him—took me to my grandmother’s house. As we made our way through town and into the old mill-community where she lived, my heart would begin to open. I knew that, within minutes, I would be embraced by love and nourished by something warm. And I was. As we pulled in the driveway, I could see her peering through the kitchen window, past the bird feeder, looking for us. Hearing our car doors close, she would wipe her hands on her apron and open the door of her small porch. She would put her hands on my face, feign astonishment at my growth, and then bury me in her arms. We sat on the porch, the three of us, talking about school, about relatives, and about the garden—her hand gently patting my own. At some point my dad would leave to “run errands” (read: take a nap) and she and I would be alone. This was my favourite moment. As he drove away, she would say with a smile, “Well, let’s go inside and see if we can find something good to eat.” She led me by the hand, into the kitchen, and onto a small stool—my stool, as I thought of it—beside the counter where the day’s ingredients lay arranged in neat little piles. These were hours of quiet bliss. Sitting there with my legs dangling over the stool’s edge, watching her work, hearing her stories, being offered some glistening spoon, setting plates on the table, and folding napkins by hand. And then we would sit, the two of us, at a small round table surrounded by windows framed by dogwoods and chorused with birdsong. After a prayer, we handed the bowls to one another: creamed corn, garden tomatoes, Vidalia onions, salmon cakes. I remember her laughter as the juice of a cantaloupe ran down her chin, and her words, “This is so good to me.” It was good to me too, all of it. A rare moment when I felt seen, safe, and satisfied. A moment when the Wanderer found the shore.

As I described these moments to my therapists at Onsite, they helped me begin not only to isolate those feelings but also to trace them and follow the thread of welcome throughout my life. To my delighted surprise, I found that they were not as rare as I, in my pain, imagined them to be. Though I had for so long believed in the inevitability of my exile, I had also known the grace of faithful embrace. I knew it from my father, who traced the lines of my face with his smoke-scented hands as I fell asleep in his bed. I knew it from my sisters who held my hands and spoke their love (and still do). I knew it from my extended family members, who, with a wink, put an extra helping of dessert on my plate and folded dollar bills into my small hands. I knew it from my boyhood friends, who invited me to their lunch tables and to their parties, and who willingly shared with me the idle joys of childhood summers. I knew it from their parents, who welcomed me into their homes, fed me in their kitchens, gave me water when I was thirsty, and Band-Aids when I was hurt. I knew it from my church youth group leaders who took me to breakfast, took me on trips, and—perhaps most importantly—took me seriously. I knew it from mentors who saw my unsteady hopes and showed me the way to go.

And I know it now. I know it from my friends, people of extraordinary beauty and grace who—time and again—have made room for me. I know it from my wife, a woman who has—beyond all others—devoted herself to creating a space of love and grace for me. And I know it from my children, who—even now—continue to make their way into our bed and lay their heads on my astonished heart.

For my entire life I craved these moments with desperation and, when they came, experienced them wistfully as mere fleeting reprieves from the howling loneliness I believed to be the inescapable core of my life. But what I could not see—not until I was invited to see it—is that these were not, in fact, transient aberrations in a life of homelessness, but were, to the contrary, fixed and constant invitations to the reality of home. They were reliable witnesses to what I most longed for but least believed: that the story of my life is not a story of unwelcome, but of welcome. And that this welcome will be found not simply in one, but in a thousand shining doorways. As long as I can remember, my secret question was, Where do I belong? What my time at Onsite helped me begin to see is that throughout my life—in every open door, every kind embrace, every fragrant kitchen, every warm plate, and every quiet guest room with towels folded on the bed—that question has been faithfully and repeatedly answered. You belong here.

On my best days, I believe this. But there are many days when I do not. I am not yet at rest, and I am not yet whole. Though I left my first home nearly forty years ago, I remain, in some remote and frightened place, the boy with the suitcase. And part of my work each day is to go to that boy, to coax the suitcase from his hand, and to help him unpack his things and find rest in the life that is now his. The work takes many forms, as noted above. But one of the most recent and experimental channels is learning how to do woodworking. Bruce had an enviable woodshop, and when he died several years ago, its contents became mine. He told me once that woodworking quieted his mind and pulled him into the world outside his head. And so, as a way to connect with him and with that world, I decided to learn the craft. On the first night of my class, the instructor, a wood wizard named Rob, asked me what I’d like to learn to make. “Something for the kitchen,” I said. “Great,” he said. “What do you have in mind?” After thinking for a moment, I said, “How about a stool?”