O

Imagination in the Ruins

On Monday evening of January 30, 1956, Martin Luther King Jr. stepped to the pulpit of Montgomery’s First Baptist Church. He was weary. As he looked out at the overflowing congregation, he knew they were weary too. The strain of the now two-months-old bus boycott—the daily foot travel, the threat of job loss, the petty harassment, the political opposition, and the atmosphere of violence, all with little to show in return—had begun to fray the hope that had marked this community just weeks before.

In the early days of the boycott, his words had lifted the community in a way that seemed almost miraculous, conveying not only the rightness of their cause but also the beauty of it. And nearly every night of the past seven weeks, they had come to listen as he rendered their ordinary sufferings in the elevated language of the kingdom of God.

On this particular night, nearly two thousand of them had come. Word had spread that the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) had decided to take the momentous step of proceeding with a federal lawsuit challenging the constitutional legality of segregation. Up to this point, the MIA’s bus-boycott demands had been framed within the boundaries of segregation: they sought courtesy for African American passengers, more designated seats, and more African American drivers. But even these demands had proved too much for Montgomery’s leaders. In spite of multiple attempts at negotiation, the city remained locked in a stalemate from which neither side would retreat. The MIA’s executive committee believed the time had come for more decisive action: no longer would they simply boycott for equality within the context of segregation; they would now challenge the system of segregation itself. They were crossing a threshold and they knew it.

The task of presenting this decision to the community fell to twenty-seven-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. This was no surprise, of course. Not only was he the president of the MIA; he was also the voice of their cause. And yet as he spoke, King’s words seemed uninspired. His explanation of the rationale and implications of the federal court case lacked his typically soaring rhetoric. To the contrary, his manner was notably professorial, even tedious. But more notable than his manner was his mood. He seemed agitated and discouraged. The burdens on his shoulders—a young family, a suffering congregation, a civic leadership role, a life shadowed by the constant threat of violence, and now a federal court case—were bending him low before their eyes.

As he finished and walked down from the podium, Mother Pollard—a now legendary figure in the boycott—stood and made her way to the front of the church. She called the young pastor to her side. “Come here, son,” she said. “Something is wrong with you. You didn’t talk strong tonight.” King protested, “Oh no, Mother Pollard, nothing is wrong. I am feeling as fine as ever.” Unpersuaded, she replied, “Now, you can’t fool me. I knows something is wrong. Is it that we ain’t doing things to please you? Or is it that the white folks is bothering you?” Before King could respond, she said—loudly enough for the whole congregation to hear—“I done told you that we is with you all the way. But even if we ain’t with you, God’s gonna take care of you.” As she made her way to her seat, with the crowd cheering and King in tears, she had said more than she knew. For in those very moments, just a few blocks away, the young pastor’s home—with his wife and young child inside—had been destroyed by a bomb.

King’s first sense that something was wrong came a few minutes later, during the offering. A young messenger entered the building and hurried to the side of Ralph Abernathy. Abernathy, the pastor of First Baptist Church and King’s friend, hurried out of the room and returned minutes later with a sick look on his face. As more messengers arrived, King, standing at the front of the church, gestured to Abernathy to come and tell him what was happening. Lowering his voice to a whisper, he replied, “Martin, your house has been bombed.” King asked about Coretta and the baby, but Abernathy had no information. King then stepped to the pulpit and asked for the congregation’s attention. With a calm that was to become his trademark, he told them what had happened, asked them to go to their homes in peace, and exited abruptly from the church’s side door.

The crowd did not go home in peace. King left the sanctuary to the shocked cries and angry shouts of his parishioners, and before he had even arrived at his home, a crowd of several hundred—armed with sticks, knives, and guns—had descended on his front lawn. The frustration of the past weeks—the past years—was beginning to boil over.

Outside the home, the angry crowd encountered a barricade of white policemen. This did not improve their mood. Just weeks earlier the Montgomery city commissioner in charge of the police, Clyde Sellers, had publicly joined the White Citizens Council, a move that had, in the words of the Montgomery Advertiser editor Grover Hall, effectively turned the Montgomery police force into an “arm of the White Citizens’ Council.” In the minds of those in the crowd, the policemen behind the barricades were themselves the perpetrators of the crime. Some stared at the barricade in silence, others shouted angrily at the police, and still others began to agitate for violent confrontation.

The small bomb, thrown onto the front porch, destroyed the front of the home. The porch steps and much of the supporting brickwork were gone. The white wood of the ceiling and walls hung down in broken shards, and the black frame of the front door gaped awkwardly. As King made his way through the crowd and inside the home, he found reporters, the fire chief, and Commissioner Sellers gathered in the wreckage of the front room. They gestured toward a back room where he found Coretta and baby Yolanda—shaken but mercifully unhurt—surrounded by members of his own Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. They greeted one another in relief, checked one another over tenderly, and offered a brief prayer of thanks in the midst of the ruins.

The moment would not last. The scene outside grew increasingly volatile as the crowd demanded to know the condition of the King family. As violent racial conflict grew imminent, Sellers asked King if he would speak to the crowd and try to calm things down. King agreed. He stepped out into the night, stood on the shattered porch, and—in view of them all—raised his hands to speak. “Everything is all right,” he said. “Don’t get panicky. Don’t do anything panicky. Don’t get your weapons. If you have weapons, take them home. He who lives by the sword will perish by the sword. Remember that is what Jesus said. We are not advocating violence. We want to love our enemies. I want you to love our enemies. Be good to them. This is what we must live by. We must meet hate with love.”

The Moment of Imagination

What was happening in that moment, when the young black minister stepped out onto the ruins of his white home, faced a volatile crowd, and asked them to love? In one respect, it was an act of pastoral care for his people. As King looked over their aggrieved faces, he knew they were sinking under the weight of their grief and despair and, as their pastor, used this moment to lift them up. In another respect, it was an act of intercession on behalf of his enemies. The Southern social order was, in many ways, predicated on African American compliance with the order of segregation. And though whites and blacks feared one another, direct confrontation between them was relatively rare. But as Sellers and his officers peered out into the growing crowd, they beheld the sight most feared by Southern whites: black humanity, indignant and unafraid. King saw this too, knew instinctively that white Montgomery was in danger, and stepped forward to intercede on behalf of his enemies.

And yet there is another possible rendering of this moment, one that is perhaps more important: When Martin Luther King stepped out onto the porch and began to speak, he did so not simply as an act of pastoral care on behalf of his people, or of intercession on behalf of his enemies, but as an act of moral imagination on behalf of his nation.

Here is what I mean: Democracy is an improvisational polity. It is, of course, rooted in foundational convictions regarding individual liberty, self-governance, and the rule of law. But the moral energies that fund those convictions and the social shape those convictions take have an unavoidably dynamic character. Though democratic convictions endure, democratic constituencies—and the institutions they create and inhabit—do not. Those who participate in a democratic polity must therefore perpetually reimagine both its meaning and its possibilities.

Historically speaking, there are moments when the need for reimagination seems fairly remote—moments of (relative) civic stability, economic fruitfulness, and international peace. And though these moments are never without contest, they nonetheless can give the impression that the work of democratic life is largely that of reform: small adjustments to the shape of the current order. But invariably these moments of democratic stasis do not endure. In time the inherited paradigms for negotiating common life simply break down. When this happens, democratic society enters into crisis, a tumultuous struggle to reinvent and rearticulate the meaning of its own life. And in these moments of crisis, the work of common life is no longer the work of mere reform but that of reimagination—the work of re-envisioning the very meaning of our shared life.

Those who participate in a democratic polity must perpetually reimagine both its meaning and its possibilities.

This was the sort of moment into which Martin Luther King emerged when he stepped out into the dark that January evening: a moment of reimagination. Indeed, it was a small part of a much larger moment of crisis—the civil rights movement of the mid-twentieth century. Since the end of Reconstruction, the racial, economic, and cultural tensions inherent in American life had been largely managed through strategies of private terror, public violence, and political theatre. But in the middle of the twentieth century—owing largely to demographic, economic, and ideological shifts in postwar America—these strategies began to fail. The moment for reimagining American democracy had come.

Because of this, King’s steps are best understood as a movement not simply into the grief of his people or the peril of his enemies but into the crisis of his nation, whose tenuous strategies for peace were in open collapse. His raised hands were not simply a demonstration of personal safety or an indication of a desire to speak but an intervention in his nation’s dissolution. And his words were not simply an act of pious oration offered in the service of the status quo but one of moral imagination offering a new vision of life together.

Our Inherited Imagination

It is critical to remember, however, that as King spoke into the darkness that evening, he did not speak into a cultural vacuum, a space without moral imagination. To the contrary, he stepped into the suffocating thickness of an inherited imagination. It was this imagination that, from the beginning of the American experiment, provided moral sanctuary for a white supremacist social order. It was this imagination that, just ninety years earlier, drove the nation to civil war. It was this imagination that, in the cold darkness of January, brought his home to ruin and his neighbours to the threshold of violence. Perhaps above all things, it was against the backdrop of this inherited moral imagination that he spoke that evening.

In his magisterial work The Christian Imagination, Willie James Jennings explores the character of this imagination by tracing its roots back into the courts and cathedrals of early Christian imperial Europe. This culture, he suggests, was formed not simply out of a history of tribal warfare, the rise of Christianity, the experience of devastating disease, the emergence of economic opportunity, or the expansion of political ambition. It was also formed by the emergence of a distinctive way of conceiving, instantiating, experiencing, and legitimating the shape of common life—that is, by a distinctive moral imagination. This distinctive imagination, he suggests, animated European colonial ambition and shaped—and continues to shape—the cultures that emerged from it.

But what was the character of this inherited imagination? While the answer he gives is as complex as it is lyrical, Jennings suggests that this moral imagination consists of five core elements.

First, it is hierarchical. Our inherited imagination is predicated on putatively fixed theological and biological distinctions between groups of human beings, distinctions that are at once morally meaningful and socially consequential. It was an imagination anchored in the distinction between saint and sinner, strong and weak, master and slave, sophisticate and savage.

Second, it is dominative. Our inherited imagination is instinctively committed to establishing and maintaining that hierarchy through the active subjugation—political, economic, bodily, and spiritual—of those lower in the hierarchy beneath those higher. It is, in this sense, an imagination indivisible from and committed to a comprehensive form of violence.

Third, it is displacive. Our inherited imagination is one in which those at the top of the hierarchy, by means of violence, instinctively seek to remove any obstacle that impedes either personal desire or political ambition. As with the previous characteristics, this displacement takes many forms, displacing people not simply from their land but also from their relationships, their culture, their language, their religion, their identities, and, finally, their very existence.

Fourth, it is extractive. Our inherited imagination is animated not only by the view that the natural world—apart from its other qualities—is finally a resource to be used but also by the will to use it to exhaustion.

And fifth, it is sanctimonious. Our inherited imagination is serene in the conviction that both its account of the world and its various actions within it are expressions of divine will. Following a harrowing inner logic, then, this moral imagination, having reified a hierarchy, proceeds on its basis to dominate others, displace them from their lives, and extract whatever it deems of value from the world, and to do so all in the name of the Triune God.

A brief aside: In a great deal of writing today, including my own, this moral imagination is referred to as a colonial imagination. Jennings, however, with a shrewd and wounded irony, refers to it as the Christian imagination. Not, of course, because he believes it to be biblically Christian in substance, but because he rightly sees it as the imagination that both animated Christian European imperial culture and animates so much of the Western Christian culture to which these empires gave rise. For those of us who consider ourselves part of the Christian church in the West, Jennings’s choice requires—at the very least—sustained and sober self-reflection.

Whatever its name, however, this was the imagination—hierarchical, dominative, displacive, extractive, and sanctimonious—that animated the moral, economic, political, agricultural, and social character of the West. And it was to this imagination—indeed, in defiance of this imagination—that King spoke on that January evening.

Imagining Cultural Change

From the beginning, Christians have understood themselves to be agents of social change. In some cases this change was conceived through small but significant acts of sacrificial love, especially toward those who live without love. In other cases it was conceived as the large—indeed, global—responsibility to remake the very structures of human society. In still others cases it was conceived simply as the work of bearing deliberate witness—liturgical and ethical—to a different and compelling way of life until all things are, at last, made new. Christianity is, in other words, fundamentally devoted to some version of cultural change.

So it should come as no surprise that the same is true of many contemporary expressions of Christianity in the West. In every society one can find both individual Christians and Christian communities who take up this work in each of the forms above. However, in addition to these local commitments toward cultural change, Western Christianity is characterized by a distinctive commitment to reflection on strategies for cultural change—which approaches to cultural change are not only morally appropriate but also discernibly effective. These strategic reflections are by no means uniform. To the contrary, they emerge from different (and often contradictory) theological convictions, are articulated with various degrees of conceptual depth, and aspire to divergent cultural ends. Because of these factors, any attempt to distill them (such as the one I am about to undertake) is fraught with the peril of oversimplification. Even so, I believe that, in spite of their rich diversity, many Christians in the West largely pursue cultural change through one of two strategies.

The first of these is the political strategy. This strategy takes a number of (apparently incongruent) forms. For some, the goal is to elect public officials with certain convictions. For others, the goal is to author, pass, and ultimately adjudicate legislation with certain implications. For still others, the goal is to characterize both themselves and their cultural enemies in terms that are politically consequential. And while Christian political strategies for cultural change express themselves variously—frequently disagreeing over character, legislation, and terminology—what is common to them all is a commitment to bringing about cultural change through the instrumentality of the state.

The second strategy is the institutional strategy. In this strategy, the key to cultural change is not so much the political instruments of the state as the institutional structures of the culture. This approach, too, is varied in form. For some, the goal is simply to live as faithful Christians in the institutions in which we find ourselves—the classroom, the boardroom, the war room—in the hope of orienting the work of those institutions toward light. This impulse can be readily observed in the prayers of virtually any small gathering of Christians in any community, in the recent proliferation of “fellows programs,” and in rapidly growing ministries devoted to the integration of “faith and work.” For others, the goal is more expansive: not simply to inhabit an institution as an individual Christian but to cultivate networks of Christians—both within and across institutions—at every level of society. In this expanded vision, the work is to deliberately catalyze institutionally significant collaboration across every “sector” of culture, in the hope that through such efforts and over time, culture itself will orient toward the light. This impulse, too, can be readily discerned, whether in private conversations between institutional leaders, at public conferences devoted to cultural change, or in the admiring personal regard with which Christian institutional leaders—especially those of great prominence—are beheld. And, again, while these respective local and expansive strategies often differ in conception and in scale, they nonetheless share the commitment to changing the culture by changing the character of its institutions.

Sensing the reader’s alarm, let me hasten to say that my intention here is neither to critique these approaches nor to elevate one over the other. For my own part, I believe that a credible Christian case can be made both for and against certain expressions of each of these, and for others besides. Strategic discernment is not my present concern.

My concern, rather, is that while many Christian communities devote considerable energy to discerning the “best” strategy for cultural change, it is not at all clear that we are equally devoted to discerning the moral imagination that meaningful cultural change requires. Indeed, it is clear to me that we are not. But, as Jennings has shown, moral imagination is the foundation of cultural life. As King understood, apart from meaningful change in moral imagination, significant cultural change is, literally, unimaginable. The implication of this for contemporary Christianity in the West—and this is my true concern—is that no matter how sophisticated our strategies for cultural change may be, if they are not animated by a transformed moral imagination, they are agents not of change but of sameness.

While many Christian communities devote considerable energy to discerning the “best” strategy for cultural change, it is not at all clear that we are equally devoted to discerning the moral imagination that meaningful cultural change requires.

This is precisely what we see in our midst. Consider many current expressions of the political strategy. Even the most cursory glance at our current political culture—much of it enacted and defended by Christians—reveals that for all its breathless promises of newness, it is simply an expression of the old imagination. Indeed, it is its apotheosis: hierarchical in vision, dominative in method, displacive in goal, extractive in fruit, and sanctimonious in rhetoric. Columbus himself would be at home among us.

So too the institutional strategy: many who espouse it eschew the crass rhetoric and naked power hunger of the political sphere, but what—in the end—is the difference between many of our Christian strategies for cultural change and the strategies used by the imperial powers to bring this very culture into existence? Do we not see the same obsessive desire to access elite institutions, attain power within them, deploy this power to create space for like minds, and use these institutions for our own cultural ends? And do we not do it all in the name of God? Is this not the lurking presence of the old imagination? Apart from the transformation of our moral imaginations, the difference is, tragically, virtually nothing.

What this shows us—and what King understood as he stood on the shattered steps of his home—is that apart from a deliberate effort to interrogate and cultivate our own moral imaginations, much of what passes as cultural change in Western Christianity is, in reality, simply the reinforcement of the old culture by new strategic means. Because of this, I believe that if churches are truly concerned about cultural change, it is imperative that we devote ourselves not first to political and institutional strategies that enact that change but to the moral imagination that makes meaningful change possible.

The Convivial Imagination, Again

And with this, we turn once again to the convivial imagination and to a deeper consideration of both its character and its significance. In my articles at The Welcome Table, I have suggested that the deliberate cultivation of this imagination—an imagination anchored in a vision of life together—is one of the most important moral and civic tasks of our time. And in each of the articles I have tried to illustrate its fundamental importance to our social healing, to our public memory, to our embrace of difference, and to our relationship to the earth itself. But it is perhaps here, in our consideration of cultural change, that its fundamental importance becomes most apparent. Why? Because only conviviality can overcome conquest. Because only the convivial imagination is powerful enough to heal the ravages of the colonial one. Because it is the convivial imagination—and this imagination alone—that can invert the old order and lead to the healing of our common life.

Where the colonial reifies hierarchy, the convivial presumes equality, a table at which all are welcome. Where the colonial valorizes domination, the convivial prioritizes service, submitting ourselves to others for their good. Where the colonial craves displacement, the convivial celebrates embrace—the open door, the warm fire, the room made ready. Where the colonial hoards through extraction, the convivial nourishes with care and bestows with generosity—a cultivated field, a laden table, a blessing on the way. Where the colonial bellows with bloviating sanctimony, the convivial enjoys the quiet delight of the sacred. It is here—in the convivial imagination—that we will find the wisdom, strength, and joy necessary to transform both our fearful hearts and our weary communities from places of conflict to spaces of communion.

For this reason I believe the foundational work of cultural change in our time is, in spite of their obvious significance, not that of refining our strategies, promoting our policies, or even reforming our institutions. Rather, it is transforming our moral imaginations. Until we do this, no matter how strategically shrewd, politically dominant, or institutionally effective we are, we will never see the fruit of love in our midst.

Centring the Imagination

Nearly eight years after King stood in the midst of the crowd gathered around him in the darkness of Montgomery, he found himself once again standing in the midst of a gathered community. This time, however, the community consisted not of hundreds but of hundreds of thousands, not simply of his neighbours in Alabama but of his fellow citizens from across the nation. They had travelled by bus, by car, by bicycle, and by foot, and were now gathered in the warm August sunlight to take part in what was, at the time, the largest mass gathering for racial justice in American history—the March for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, DC.

As King, one of a number of important speakers, stepped before them onto the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, he saw a markedly different scene than the one he had beheld all those years ago in Montgomery. Instead of weariness he saw energy. Instead of anger he heard joy. And instead of defeat he sensed a ubiquity of hope. Looking beyond the gathered crowd, he saw the United States Capitol, the place where the denial of his humanity—and the humanity of millions before him—had been codified into a political order. And to his left, in the distance, he saw the White House, where President Kennedy and his advisors anxiously gathered to watch the day unfold. He stood, in other words, before a crowd representing the entire scope of a culture born of the colonial imagination, and did so with the purpose of transforming that culture into something new.

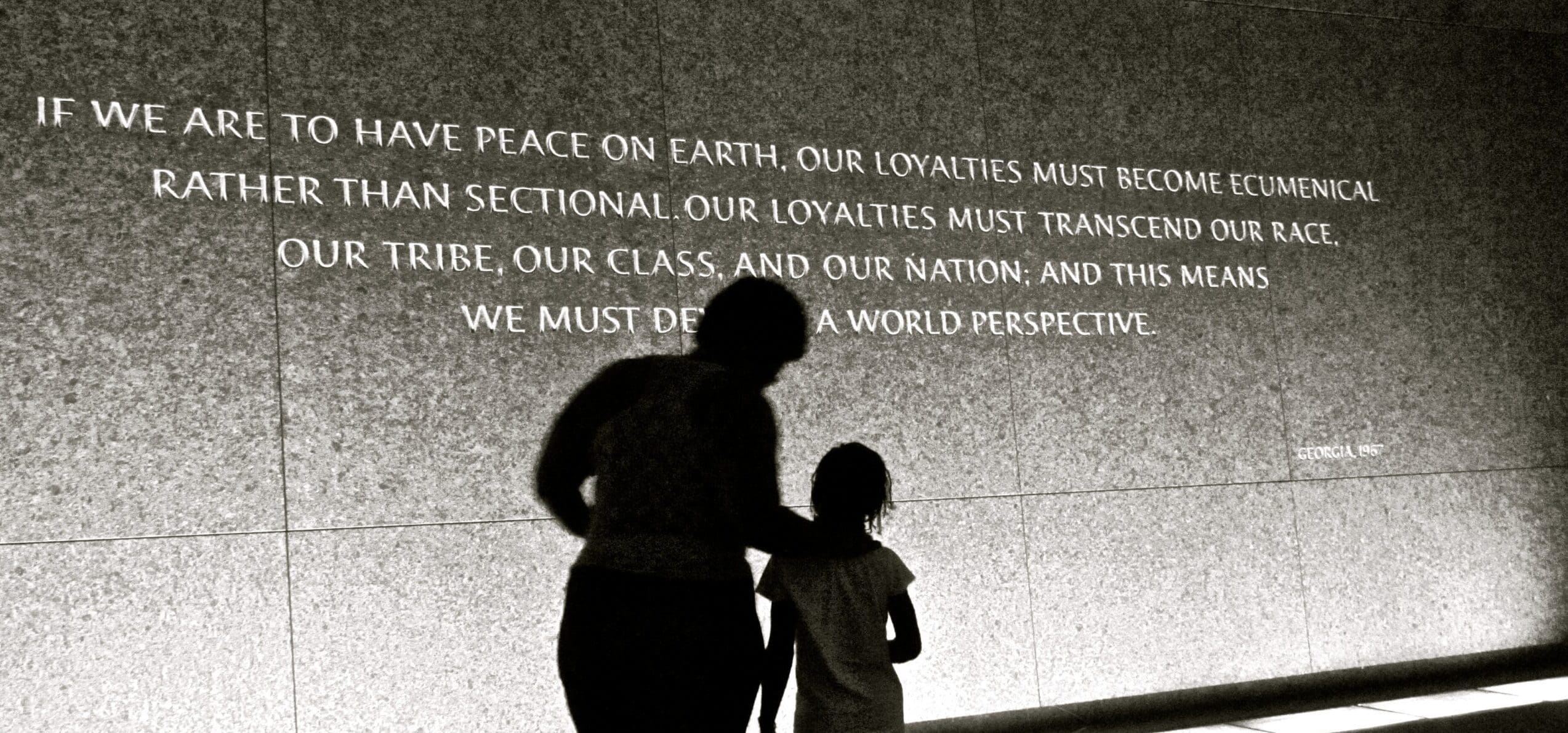

The words he spoke on that day, into that community, and with that transformative purpose are among the most famous in history. They are inscribed in stone, printed on clothing, and lifted in song. Indeed, for many millions of people across the world, they are a touchstone for the possibility of cultural change. Why? Is it because of the depth of their lyricism? Partly, of course, but the truth is that King gave many lyrical speeches—including portions of this one—that are largely forgotten. Perhaps it is because of the sophistication of the strategy they offer? This, too, is unlikely, for apart from a few exhortations to nonviolent peacefulness—these, too, offered in greater depth elsewhere—King offers virtually no strategic direction at all. Perhaps, then, it is the clarity of his policy suggestions. This is the least plausible of all: there is not a single policy mentioned in the entire speech.

We, like King, are in a moment of civic crisis; we are a culture desperate for meaningful change.

Why, then, is this speech so famous? Because it offered Americans, in the midst of a crisis of democracy, the one thing most needful: a dream. By its very existence, King’s speech offered the dream of African American significance in a racial hierarchy predicated on their debasement. Through its exhortations to peace, it offered the dream of a world beyond dominative violence. Through its very setting, it offered the dream of democratic belonging for the displaced. Through its explicit evocation of access to American abundance, it offered the dream that those who had borne the injustice of extraction might one day come into their rightful inheritance. Through its evocation of God’s prophetic word, it exposed the tired hypocrisy of American sanctimony to the sacred light of justice. Through its soaring evocation of a society in which “all God’s children” join hands in song and labour for freedom, it contested the very essence of the society to which the colonial imagination gave birth, and replaced it with an explicitly convivial vision of life together. The reason King’s speech is so foundational to the work of cultural change is that it was, in its essence, a work of moral imagination, a speech that—even as it contested both the logic and the fruit of the colonial imagination—offered the nation an alternative vision of the possibility of its life together.

In my first article for The Welcome Table, I wrote that

across much of North America, many of the long-standing features of our tragic colonial inheritance endure: racial and ethnic hostility, institutionalized injustices, material inequality, social mistrust. Each of these, of course, is now heightened by an intractable and highly politicized form of identitarian tribalism sustained through the willed cultivation of historical amnesia, set against the backdrop of undeniable symptoms of ecological death. The fruit of all this is evident everywhere around us: anger, confusion, self-protection, a ubiquitous weariness of heart.

I am convinced, in others words, that we, like King, are in a moment of civic crisis; we are a culture desperate for meaningful change.

But like King I also am convinced that while strategy, politics, and institutional renewal are deeply important, cultural change can never truly come to be without serious and sustained reflection on our individual and collective moral imaginations. Put more plainly, cultural change cannot happen until the church in the West overcomes its obsession with strategies political and institutional, renounces the colonial imagination that infects so much of our common life, and, as an act of both repentance and love, deliberately centres the work of cultivating a convivial imagination. Put more plainly still, if this broken moment is ever to be healed, it will not be because we became architects of strategy or masters of policy, but because we became what we most need to be: dreamers of dreams.