T

The Shared Table

The spring of 1865 found Mrs. Abby Porchet in deep distress. Sometime in the previous winter, Mrs. Porchet, along with her family, had fled her hometown of Charleston, South Carolina, as word of the Union Army’s impending arrival reached the city’s elite. For the past many weeks, living a life of exile in the foothills of Greenville (my hometown, as it happens), she, along with many of her neighbours, awaited news of the worst.

The news came in successive waves. First came the news of occupation. In February, Union soldiers entered the city, accepted terms of surrender, took possession of homes and businesses, and established a provisional government. Charleston, the home of Secession, was now the epicenter of occupation. Next came the news of emancipation. Following the occupation, the officials of the newly established provisional government enforced the Emancipation Proclamation and freed Charleston’s nearly ten thousand enslaved African Americans. For Mrs. Porchet, these two events signalled the end of her cherished social order and raised the spectre of her family’s descent into a new life defined by displacement, poverty, and ignominy.

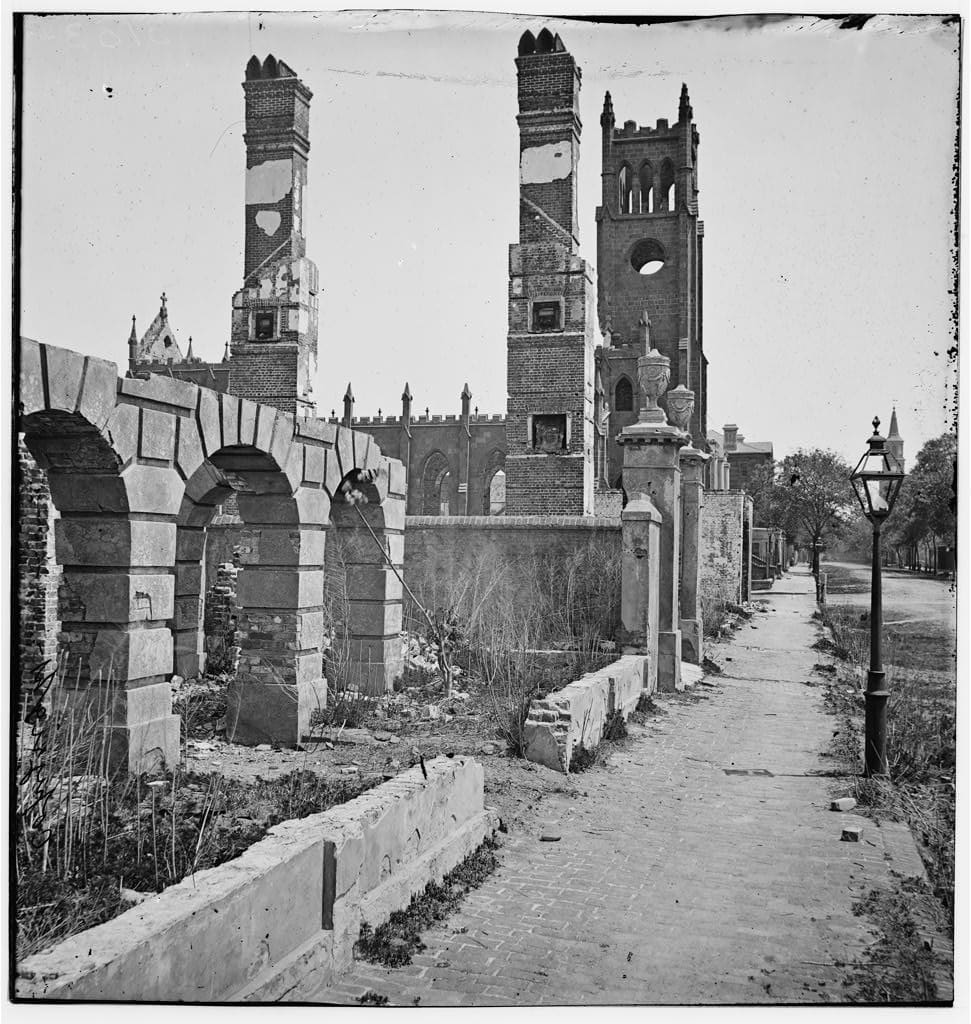

Broad Street, Charleston, 1865

Most distressing of all, however, was the news of celebration—specifically, news of a feast being held in the heart of old Charleston. The feast, rumours had it, was being presided over by Nat Fuller, a formerly enslaved yet highly regarded chef, caterer, and restaurateur who had prepared food that Mrs. Porchet herself had undoubtedly once tasted. To hear that Fuller, an African American man, was hosting a feast while she was in exile was infuriating, and to add insult to injury, there were also reports that the feast was the most sumptuous held in Charleston in recent memory.

For the past several years, the Union army’s blockade of the harbour had slowly starved the city, reducing the once magnificent tables of Charleston’s elite to the sullen shape of rationed survival. To hear that those tables were once again magnificent, but that she herself was kept from them, was galling. But most sickening of all was the news of the feast’s attendees. The banquet, if the rumours were true, was one in which a number of Charleston’s African Americans sat and dined together as equals with white Union soldiers and white members of the provisional government. It was said that together they raised their glasses, toasted Lincoln, and sang songs to freedom. As Mrs. Porchet wrote in a letter, “Nat Fuller, a Negro caterer, provided munificently for a miscegenat dinner, at which blacks and whites sat on an equality and gave toasts and sang songs for Lincoln and Freedom.” For her, it was this news—this news of a shared table—that not only portrayed the end of the life she knew but also presaged the arrival of the future she feared.

For her, it was this news—this news of a shared table—that not only portrayed the end of the life she knew but also presaged the arrival of the future she feared.

Meanwhile Nat Fuller was having the time of his life. Compared with the vast majority of enslaved African Americans, we happily know quite a lot about Chef Fuller. Born in 1812 as the son of an enslaved woman and a white planter, Fuller was himself enslaved. Around age fifteen, he was sent by his owner, one William Gatewood, to apprentice to the famous Charleston pastry chef Eliza Seymour Lee. Lee was a free African American woman who, alongside her husband, John, ran several successful hotels and restaurants in the city and who—not least through Fuller—would make Charleston one of the culinary centers of the nation. After several years under Lee’s careful eye hauling vegetables, preparing stocks, butchering animals, making sauces, and folding pastries, Fuller became a chef.

Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, in addition to preparing meals for his owner’s family, Fuller was often hired out to cater the events of local families and organizations South Carolina Medical Society, the South Carolina Jockey Club, the Saint Cecilia Society, and the Society of the Cincinnati. By the early 1850s, he—in a venture funded by his owner—became one of the most important “game marketers” (i.e., poultry vendors) in the city, eventually acquiring enough capital to launch his own full-service catering company. By the end of that decade, he was the city’s premier caterer and, upon opening his restaurant, The Bachelor’s Retreat, one of its most prominent and popular restaurateurs.

Though his businesses struggled during the war years, through persistent labour and flexible entrepreneurship, Fuller maintained his status as one of the city’s most important chefs. And so it was only natural that the leaders of Charleston’s new government eventually found their way to Fuller’s table, choosing his restaurant as the site for a feast celebrating George Washington’s birthday. It was also in this same restaurant that, as Mrs. Porchet would come to learn in April 1865, Nat Fuller’s “miscegenat dinner” took place.

The Feast of Reconciliation

Most of the details of that original feast have been lost to memory. In truth, that it happened at all was largely unknown until it was discovered in 2012 by David Shields. Shields, who serves as Carolina Distinguished Professor at the University of South Carolina and as chairman of the board at the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation, is a prominent scholar of Southern American foodways and the author of Southern Provisions: The Creation and Revival of a Cuisine. It was while doing research on the foodways of the South Carolina Lowcountry that he came across the above passage from Mrs. Porchet’s letter. And when he read her despondent words about Fuller’s “miscegenat dinner,” and reflected on those words with colleagues, an idea was born: in 2015, for the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, he would re-create Fuller’s feast.

In one respect this idea was driven by a scholar’s desire to correct the public record. As chef and culinary historian Michael W. Twitty, author of The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South, and many others have noted, African American chefs played a foundational role—perhaps the foundational role—in the development of “American cuisine.” And yet these important chefs—Nat Fuller surely among them—remain largely unknown outside the realm of devotees to the history of Southern foodways. For Shields, re-creating the feast and re-centering Fuller’s legacy was an opportunity to reshape public memory.

But in a much more important respect, this idea was driven by a citizen’s desire for social healing. For Shields, the genius of Fuller’s feast was that it represented an alternative vision of America, a vision of the healing of social wounds through table fellowship. As Shields put it, “Charleston is the place that drove secession. That in Charleston, at the end of the war, there was someone looking forward to a future of harmony and civility—reconciliation—there’s a certain appositeness to that. It’s just right. The healing has to start where the hurt was the greatest.”

The healing has to start where the hurt was the greatest.

The months leading up to the anniversary celebration were heavily laden with preparatory detail. Shield’s first step was to recruit an African American chef who could help research and re-create Fuller’s feast. Through a friend, he learned about the work of local chef Kevin Mitchell, chef instructor at the Culinary Institute of Charleston and secretary of the Edna Lewis Foundation. Mitchell eagerly agreed to join the project, and together they stepped into the work. They formed a committee. They established a guest list. They researched the food of nineteenth-century Charleston. They sponsored a local essay contest. They raised money. They secured venues. They rented dinnerware. They hired staff. They recruited local chefs B.J. Dennis, M. Kelly Wilson, and Sean Brock to help Mitchell execute the menu. They gave interviews with the local media and speeches to local organizations. They sent invitations with Nat Fuller’s signature at the top. And, to their surprise and delight, they received messages from other cities who were following their example and planning reconciliation feasts of their own. There was a growing sense of the significance of their work, a sense that they were—that the city was—on the edge of something sacred.

But then, just over two weeks before “Nat Fuller’s Feast” was to take place, Walter Scott, an African American man, was shot to death by a police officer in North Charleston. The video of his shooting, released days later, confirmed the worst: Scott was shot in the back while running away from a routine traffic stop. The response to Scott’s death was swift and polarizing. In a scene that, now six years later, feels tragically familiar, protestors stood on the steps of City Hall and described their experience of senseless violence at the hands of police and decried the chronic degradation of African American humanity. And yet as they did so, others rallied around the police and sought to vilify Scott, insinuating that he deserved what he received. Though the Civil War had officially ended 150 years before, in Charleston the violence and grief at the heart of that war endured.

The Breaking of Bread, the Sharing of Salt

It was against this backdrop that, on April 19, 2015, Nat Fuller’s Feast of Reconciliation was held. The evening began with a cocktail reception at 103 Church Street, one of a few possible locations of Fuller’s restaurant, The Bachelor’s Retreat. The reception was prepared by B.J. Dennis, a brilliant culinary artist of Gullah-Geechee heritage (descendants of formerly enslaved West and Central Africans who have continued to make a home on the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia) who has become one of the most important voices in African American foodways. As the eighty guests, many of whom, though local, did not know one another, exchanged cautious greetings, they shared trays of Fuller-inspired cocktails and hors d’oeuvres. The drinks, mainstays of Fuller’s era, included the mint julep, gin and bitters, and persimmon beer. The hors d’oeuvres, likewise crafted to evoke historic African American Lowcountry and coastal cuisine, included benne tarts (benne is an African variety of sesame) with lobster salad and caviar and warm rice bread (rice being the most prominent crop of the Lowcountry plantations) with smoked beef tongue and chow chow (a pickled relish). It was a taste of what was to come.

As the reception wound down, the guests stepped out into a warm spring rain and began the five-minute walk to the venue for the feast: Sean Brock’s McCrady’s Long Room, located, fittingly, on Unity Alley. As they entered, they were greeted by Chef Mitchell and his staff and seated at two long banquet tables bathed in soft light and set with linen, flowers, china, and champagne. David Shields, dressed in a dark striped suit and red bow tie, greeted guests and watched as his vision came vibrantly to life. As the guests were seated, Chef Mitchell stepped forward and asked for their attention. Gazing slowly around the silent and expectant room, he said, “These have not been hospitable times. Strife and sorrow have for too long had the upper hand. As you know, war is not my work. My study is to make people enjoy the time that they spend together. It is an ancient custom that once people sit at a table and break bread and share salt, they shall do no harm to one another.” And with that, he encouraged his guests to share their lives with one another, offered a prayer for the meal, and began service.

The menu, in classical nineteenth-century style, was a journey through seven magnificent courses, each one making a point. Some highlights: The first course, Potage, offered turtle and oyster soups from the local marshland. The second, Relishes, straightforwardly challenged racial stereotypes by offering pickled watermelon and a “kraut” made of fermented collard greens. For the third course, Poisson (seafood), the guests were served fried whiting and shrimp pie, both staples of African American foodways, each elevated with its own distinctive sauce. For the poultry course (Volaille)—in honour of Fuller’s years as a game marketer—the chefs prepared capon chasseur (rooster with mushrooms, tomato, and white wine), aged duck with Seville oranges, and partridge with truffle sauce—each a gesture toward Fuller’s training in classical French cooking. Likewise, Viande (the meat course) boasted venison with currants, lamb chops, and beef à la mode. The vegetable course (Legumes) combined local garden produce of the kind enslaved workers grew for themselves with the Carolina Gold rice that they grew for their owners. And finally, Desserts featured charlotte russe (a cake reserved for special holidays) and pineapple ice cream. The menu, in other words, told Fuller’s story: an enslaved man who, by combining local ingredients with classical technique, produced a cuisine of both resistance and reconciliation.

Throughout the meal, the guests laughed, talked, and—as Chef Mitchell requested—told each other the stories of their lives. And as Shields looked across the room, he could see the seeds of healing; the faint outlines of that original Feast of Reconciliation appeared.

As the last course was served, Shields stood to offer a toast, saying, “This must have been the first space in Charleston where people of so broad a range of ethnic background and history had the opportunity to speak their mind in so candid a way. Only one of the toasts of that original feast has come down to us. And I’d like to repeat it now.” After noting that the original feast took place just days after Lincoln’s assassination, he raised his glass and offered that toast: “To Lincoln and Liberty.”

Over the next hour, many of the guests made toasts of their own. They praised the chefs. They told stories. They read poems. They honoured one another. And they pledged to go out from this feast and pursue the work of reconciliation at feasts of their own. It was, by all accounts, an extraordinary evening at the table, an evening that seamlessly integrated the convivial, the political, the ecological, and—to some—the theological. As Shields put it, reflecting on Fuller’s original feast, it was “a glimpse of the kingdom of God.”

In the Presence of My Enemies

Two months later, one of the guests at that feast, the Reverend Clementa Pinckney, sat in the basement of his church, Mother Emanuel AME, reading about that same kingdom with a small group of his parishioners. Mother Emanuel, the oldest African American church still standing in the American South, has long been associated with the struggle against white supremacy. Indeed, in 1822, in retaliation for parishioner Denmark Vesey’s planned slave rebellion, the church was burned to the ground. And Pinckney, who, in addition to his role as pastor, served as a South Carolina state senator, carried on this historic legacy of resistance. Perhaps thinking of Nat Fuller’s feast, Pinckney and the others welcomed a stranger, a young white man, into their midst. As they concluded their evening study and began to pray, the young man stood, pulled a gun from his bag, and shot Pinckney and eight others to death.

The facts of this horrific crime are broadly known, and its impact continues to reverberate not only in Charleston but across the world. But one of the more curious elements of this impact is that, in the months following the shooting, Nat Fuller’s Feast of Reconciliation—an event barely known outside South Carolina just weeks before—suddenly became a matter of national interest. Indeed, in the following year, articles about the feast appeared in major newspapers in New York, Atlanta, Charlotte, and New Orleans.

Some of this attention took the form of reappraisal. Professor Ethan Kytle, for example, historian at California State University at Fresno and coauthor of the remarkable Denmark Vesey’s Garden: Slavery and Memory in the Cradle of the Confederacy, began publicly to question whether the original feast was in fact historical at all. Kytle, who was in Charleston doing research during the 2015 feast, was inspired when he learned of the event: “I was fascinated; I loved the story.” But as he began to research the circumstances about the original feast, he began to doubt whether the historical record actually told the story that Shield’s believed, eventually coming to the conclusion that the original “Nat Fuller’s Feast” didn’t happen at all. For their part, Shield and Mitchell disagree with Kytle, asserting that even if they got some of the details wrong, it is nonetheless the case that “a meal where black and white people sat together did take place,” and that their reenactment was faithful to the spirit of “what Fuller was trying to do.”

Importantly, however, Kytle’s reappraisal focused not simply on the historical accuracy of the feast but also on its social consequences. The essence of his concern was that the enchanting narrative of Nat Fuller’s Charleston feast could be used to obscure the terrible reality of Charleston’s—and America’s—racial crisis. After all, Charleston was the epicenter of the nation’s trade in human beings. It was the site of Denmark Vesey’s lynching. It was the prime mover in Confederate Secession. And now it was the site of one of the most horrific acts of racial violence in America in recent history. For Kytle, to suggest that these matters could be resolved simply by a full table bathed in soft light is both to misunderstand the nature of our estrangement and to obstruct the reconciliation to which the feast aspires. As he put it, “Charleston is a place that for too long has ignored its African-American history, ignored its potentially divisive topics. It’s finally starting to do a better job of that. But I don’t want a false story, especially a self-congratulatory story about Charleston during Reconstruction and Charleston today. I don’t want to undercut people having racial reconciliation dinners. The motives are noble. But myths have gotten us in trouble before.”

Yet even as Kytle reappraised Nat Fuller’s table, others called for a return to that table. In the months following the shooting and beyond, articles, blog posts, and podcasts spoke of the feast of Nat Fuller and of the need—somehow—to make our way once again to the table he set. Each of these was in its own way an expression of longing, a witness to the fact that even if Nat Fuller’s feast didn’t happen in the way we thought, we sorely wish that it had. And not only this, we wish that it might happen again. As the historian Kytle himself tellingly put it, “I still want the story to be true.” And in small gatherings in homes, churches, and banquet halls across the American South, people struggled once again to make it true. Indeed, it was while in Charleston for a meal marking the one-year anniversary of the shootings that I first learned of Fuller’s Feast. And it was at that table, while breaking bread and sharing salt with family members of the victims, that I first tasted something of its transformative possibilities.

In spite of the tension between them, each of these instincts—to reappraise the table and to return to it—are deeply important. The instinct toward a deeper understanding of the history of the feast and an honest acknowledgement of its real limitations is critical for guarding truth in our cultural memory and resisting naive sentimentalism in our collective practice. But just as critical—perhaps even more so—is the instinct to return to that table, the instinct, in the midst of unimaginable violence and intractable estrangement, to nonetheless prepare a table in the presence of our enemies. Why? Because together they suggest not only a longing for healing but also the presence of a holy intuition that this healing can, in the end, be found only at the table.

The instinct toward a deeper understanding of the history of the feast and an honest acknowledgement of its real limitations is critical for guarding truth in our cultural memory and resisting naive sentimentalism in our collective practice.

The Welcome Table

The Welcome Table, a new offering of Comment, is born of these two instincts. Although it would have been impossible to imagine such a thing in the summer of 2015, the world that we share now, just six years later, is in virtually every regard more deeply in crisis than it was. Across much of North America, many of the long-standing features of our tragic colonial inheritance endure: racial and ethnic hostility, institutionalized injustices, material inequality, social mistrust. Each of these, of course, is now heightened by an intractable and highly politicized form of identitarian tribalism sustained through the willed cultivation of historical amnesia, set against the backdrop of undeniable symptoms of ecological death. The fruit of all this is evident everywhere around us: anger, confusion, self-protection, a ubiquitous weariness of heart. We are, every bit as much as Nat Fuller was, setting our tables in a time of war.

So part of the work of the Welcome Table is the work of reappraisal: the work of looking anew at the complex reasons for our continued estrangement, and at why our attempts to heal this estrangement—such as they are—seem so anaemic in substance and futile in effect. Our work, in other words, is to seek to understand those things that keep us from the breaking of bread and the sharing of salt. Because of this, the Welcome Table aspires to provide its readers with creative and substantive explorations of the various sources of our estrangement—cultural, racial, ecological, and theological among them—and, in time, to do so out of an increasingly diverse array of voices. We seek, as any good host should seek, to understand—and to help others understand—the obstacles to a shared table.

But this work of reappraisal is always in the service of a much more fundamental work—the work of return. Our basic conviction, the emulsifier that holds the Welcome Table’s ranging explorations and diverse voices together, is this: we are made for communion, for table fellowship with one another. And while the work of hospitality cannot do everything that must be done for our healing, nothing of substance can in the end be done without it. We are all, we believe, bound to the table, and our work—in a fundamentally inhospitable moment whose discourse seems hell-bent on not just deepening but also valorizing our estrangement—is to contend for the convivial imagination, to insist on the moral meaning and social power of the shared table and the raised glass.

While the work of hospitality cannot do everything that must be done for our healing, nothing of substance can in the end be done without it.

So even as we reappraise, we do so in the service of return. We will seek to draw our reader’s attention to those things that both encourage and enable our collective return to the table. Our work will seek to cultivate an imagination for hospitality, to remind our readers that such a return is actually possible. Even in an age of war, there are those in every community who seek to gather up the bounty of the world and offer it to their neighbours in love: seed breeders, farmers, fisherman, foragers, vendors, chefs, food writers, and home cooks. We want to tell their stories and, in so doing, to inspire this fundamentally hospitable and convivial way of being in ourselves and in our readers.

In another respect, we will seek to cultivate the practices of hospitality. Welcome, after all, is not simply a disposition but a practice—an ensemble of practices—that creates a place where people can find one another. Because of this, part of our work is to support these practices: opening the heart, gathering and preparing food, creating and opening spaces, embracing strangers, and blessing them on their way. To this end, our articles will, by turns, find us in fields and markets, kitchens and cookbooks, food deserts and full tables, clamorous cafeterias and hospital bedsides. Each with an eye toward the practices of hospitality, each encouraging the works of welcome.

Ultimately we are doing all this with one very simple hope: that we, together with our community of readers, might embrace the exhausting and exhilarating work of hospitality as central to the life of faith, hope, and love in our time. Why? Because we believe that it is here, in the act of creating our own shared tables, that we most truly offer and fully experience—in both spiritual and sensual form—that which we and our communities most deeply desire: welcome.