A

“And the master said to the servant, ‘Go out to the highways and hedges and compel people to come in, that my house may be filled.’”

The Gospel of Luke

A Table Set with Stories

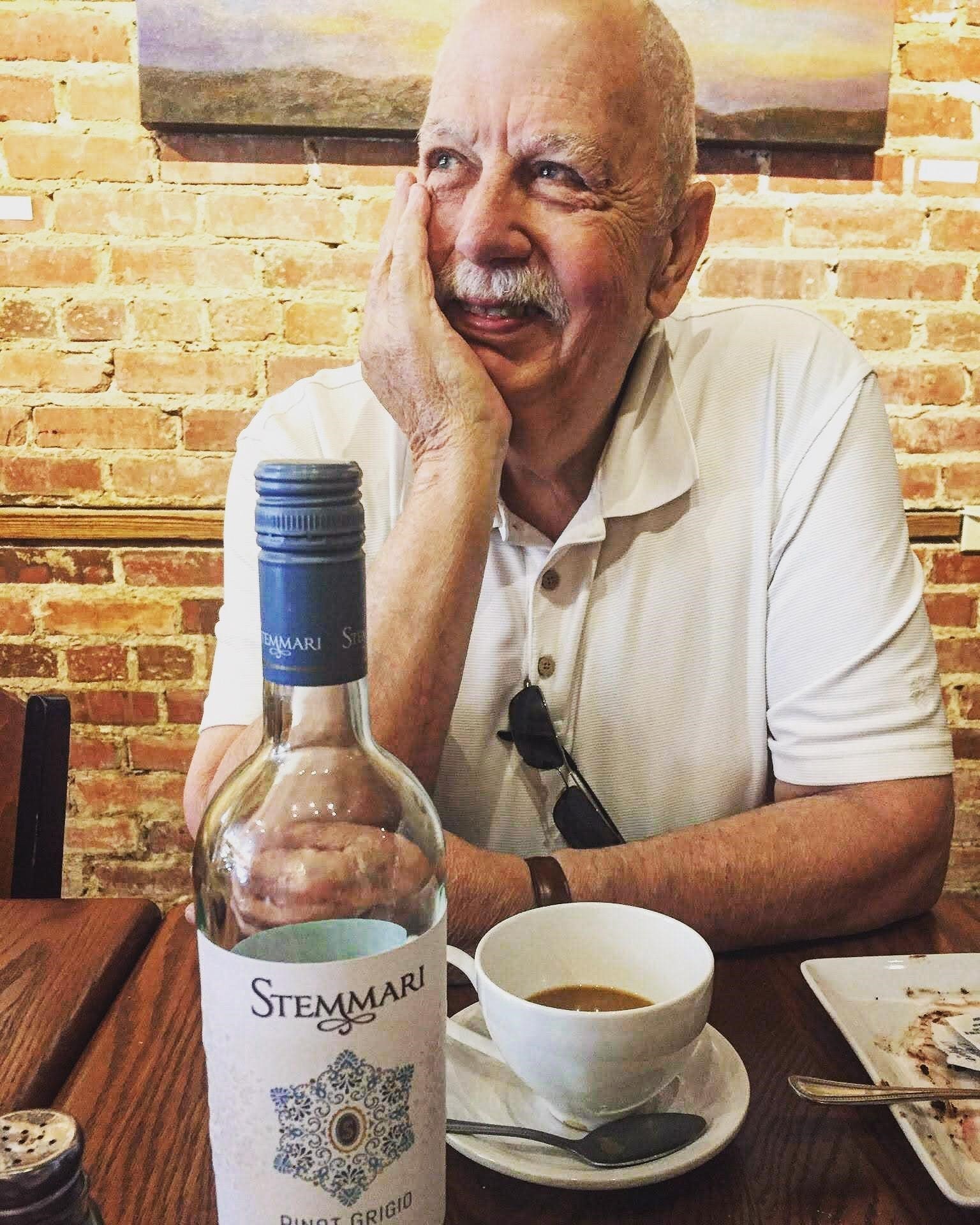

Just over two years ago I lost my father. His name was Bruce, and for reasons I never fully understood, that is the only thing I ever called him. The sobbing summons to his bedside came in the morning, and after a harried six-hour drive, I arrived that afternoon with just enough time to tell Bruce that I loved him before he drifted into a morphined mist. Several hours later, as night fell, I watched his face begin to change colour and held his hands as his heavy smoker’s lungs slowed and, in time, came to a silent stop. When I realized that he was gone, I knelt beside him and, in a lingering instinct from my years as a pastor, placed my hand on his head and managed a broken benediction: The Lord bless you and keep you.

Sometime after midnight, when the saintly hospice nurse arrived, my stepbrother and I lifted Bruce’s naked, sweaty, and now rigid body so that she could clothe him. Around 3:00 a.m., I stood silently as two gentle, if formal, men in suits placed him in a bag on a gurney. I strained for a last look as they closed the zipper over his face, loaded him into their car, and drove into the night. And then, in another lingering instinct—this time from childhood—I did the only thing I knew to do: I swiped a pack of his cigarettes, stepped into the moonless night, lit one up, inhaled his scent, and began to walk.

I am not naive about death. In my life as a pastor, I sat in silence and watched as it entered homes and hospitals and took those for whom it came. I closed the eyes of old men as their grown children stood around them. I kissed the silent curls of cooling children as their young mothers wept on the floor. I stood beside open graves and noted how, in spite of our attempts to cover it with green carpet, the undeterred soil nonetheless peeks out to remind us of its presence, of our future. And, in my life as a cook, there is a real sense in which death is the precondition of the trade: my time is spent breaking down chickens, trimming bellies from tuna, and opening walk-ins to retrieve the curing bodies of whole lambs. I was, in other words, prepared for death.

What I was not prepared for was loss. The gravelled drawl of Bruce’s voice. The smell of smoke on his hands. The appraising blue of his eyes. The comically straining knot of his apron. The victorious hint of his smile as he removed a wooden spoon from the pot and offered me a taste. All of these are lost to me now, lost to all who knew him. And, in the perverse mathematics of grief, with each day that adds to my distance from these things, the permanent surreality of their loss multiplies.

Of all the things I miss, one that I miss most is watching Bruce in action as a storyteller. It would go something like this: as he stood in the kitchen with a towel slung over his shoulder, or slid his chair back from the table and lighting a cigarette with a flick of his brushed-chrome zippo, the glint of mischief would inevitably flame up in his eyes and the stories would begin.

Some were about his life. Like the time when, as a six-year-old, he saw two larger boys gang up on his older brother. Terrified, he ran home, only to be spanked for abandoning his brother and sent back out into the fight. Or the time when, during a particularly brutal high school football game, he proudly announced in the huddle that during the previous play he had bitten the calf of an opponent’s leg to the point of drawing blood. It was at this point that he realized that the bloody calf in question belonged to his own quarterback, who proceeded to punch him in the face. Still another was the time when, as a teenager, he accidentally revealed his new smoking habit to his parents by absentmindedly lighting up at the dining room table and being subsequently knocked to the floor by his decidedly Presbyterian father. There appears to have been a lot of punching back in the old days.

Most of his stories, however, were about the lives of others. Not just any others, though. No celebrities, politicians, or people otherwise derided by my father as “big-time Charlies” ever played more than a supporting role. Invariably, the stars of his stories were the ordinary people—to my teenage mind forgettable—whom he knew. The young cowboy-welder with whom he shared a trailer during a Wyoming winter. The travelling rodeo cooks with whom he worked in Oklahoma. The young and miraculously powerful African American man, known simply as Moon, with whom he spent a legendary summer loading trucks, drinking beer, and performing feats of strength. These were Bruce’s standard set. He loved these kinds of stories, and he loved them because he loved these kinds of people.

It is true, of course, that his stories were plainly overfull with what the old-timers generously called “yarn.” The cowboy who could weld gloveless all day in a blizzard that would fell a buffalo. The tractor-trailer-sized griddle that could cook five thousand burgers at a time. The ease with which Moon could carry a full refrigerator under each arm. It was Bruce’s own personal form of magical realism. I have been told that some even considered him the García Márquez of northern Greenville County.

But even with their yarn, they were our stories—rimmed in smoke, delivered with style, and punctuated with laughter. Bruce set a table with these stories, and in retrospect I see that they nourished us every bit as much as his food. So much so that now that he is gone, I rummage through the barren cupboards of my mind to find them so that I can bring them into my own kitchen and serve them at my own table.

A Place at the Table

Unsurprisingly, I was late in coming to understand the purpose of these stories. Part of their purpose was simply personal pleasure. Bruce told them because he enjoyed them; they made him laugh and made those around him laugh. This is no small thing. In this life even the meanest pleasure is a gift, and knowing that my father not only sought pleasure but found it gives me, all these years later, a pleasure of my own.

But there was a larger purpose as well, not just personal pleasure but something like public memory. He would not have used this phrase, of course. In fact, I can say with a high degree of certainty that upon hearing it, he would have rolled his eyes in melodramatic mockery. I suspect that he is doing so now. But since he has now so thoughtlessly abandoned me, let’s go with it.

To speak of public memory is to speak of the stories that we as a people choose to remember and those that we choose to forget. Those we choose to remember become statues in our squares, names on our schools, ciphers in our speeches, and lodestars in our moral imaginations. Those we choose to forget don’t simply go away, however. They—like the blood of so many Abels—remain buried beneath us, crying out from the ground. And while we may not often think consciously of these stories—either the remembered or the forgotten—they are nonetheless foundational to our collective identity, to our common sense of who we have been, who we are now, and who we may yet become. The shape of our memory determines the shape of our lives.

To speak of public memory is to speak of the stories that we as a people choose to remember and those that we choose to forget.

In reflecting on my father’s storytelling, both the particular stories he told and the fact that he told them to me, I came to understand that he was trying, gently, to amend what he sensed was an erring instinct in my own memory—a tendency to retain the trivial and forget the important. After all, I was his weird son, the child serially obsessed with things like ninja stars, Duran Duran, parachute pants, and perestroika. He rightly suspected that if left to my own inclinations, I—along with my equally weird friends—would remember just about anything but the ordinary. He knew that I would likely fill my mind with the novel and the frivolous, becoming in time both personally insufferable and socially useless. He knew, in other words, that who I would become would, in large measure, be determined by the stories I remembered. He wanted me to remember the right ones.

I see now that his stories, viewed in this light, were an attempt to tip the scales of my memory toward those whom I might not otherwise see—or, worse, might see but refuse to regard. And so night after night, in spite of my groans (as likely as not because of them), Bruce gathered the stories of those hidden in the margins, brought them into our kitchen, and set them before us. Why? Because he understood, in a way that I could not, that the health of a table is largely determined by the stories that are welcomed there.

The Table of Our Common Life

This conflict between father and son over the stories that shape us is presently taking place not simply at our private tables but also at the table of our common life. Indeed, across the United States, the question of whose stories will or will not be told has become of central concern to our public culture and to our political debate.

There is a sense in which this question was inevitable. Over the past several years, renewed and insistent calls to confront racial injustice have emerged with force in communities across North America. In response, many people in these communities have given themselves to the work of reform across a broad array of institutions: policing, education, health care, wealth creation, voting legislation, and more. Given this, it was simply a matter of time before this national reckoning would turn its attention to the domain of public memory. Why? Because, as my old man understood, the substance of our public memory determines the shape of our public life.

But what is the substance of our public memory? What story does it tell? In reflecting on this question in the American context, the University of Pennsylvania’s Monument Lab revealed the following in its 2021 audit of over 50,000 American monuments: 94 percent tell the stories of men, and 6 percent tell the stories of women; 90 percent tell the stories of white people, and 10 percent represent people of color of any kind; 33 percent tell stories of war and conquest (hundreds of which honour the Confederate Army of the American Civil War and are sustained by over $40 million in public funds), while only half of 1 percent tell the stories of enslaved people and those who worked beside them for their liberation. Viewed simply from the perspective of the monuments we have constructed, the story of American public memory is largely one of whiteness, maleness, and conquest.

It is important to understand that this story did not emerge by accident. After the American Civil War, the broken nation faced two fundamental challenges: first, determining the political status of newly emancipated African Americans, and second, establishing a basis on which the South and North could reintegrate into one nation. From 1865 to 1877 the official answer to both of these questions was to reconstruct the American South into the shape of a racially inclusive reading of the Constitution—to create a society in which African Americans and white Americans might in some way share in the rights of democracy. In this vision, the aspirational basis of unity—however fragile—was constitutional.

This basis, however, did not endure. Because of constant resistance to Reconstruction in the South and a shift of priorities in the North, Reconstruction came to an end in 1877. As it did so, the vision of an American identity anchored in the Constitution receded from public memory. In its place emerged a new basis of American unity, a cultural basis, a shared self-concept of who “we the people” really are. And who, in this account, are we? We are white. We are male. We are Christian. And we are conquerors. That the “we” became so defined can be seen in the fact that between 1875 and 1930, in an attempt to make this cultural vision both explicit and enduring, the American people engaged in a historically unprecedented program of memorialization, erecting nearly six thousand memorials in that period alone.

When considering these memorials, it is critical to understand that they are much more than statues. They are instantiations of a cultural self-concept, features not simply of a new public landscape but of a new public memory. Indeed, the invention, legitimation, and perpetuation of that public memory—that story—is their purpose. And what story do these memorials tell? Simply put, they tell the story of white male domination, a domination that is at once evangelistic in spirit and global in scope. This is the story we have inherited, the story that occupies so much space at the table of our common life.

A Table of Exclusion

As important as this inherited story is, however, of equal importance are the stories that have been excluded. After all, others, too, lived in America. Others, too, contributed to its life. But their stories have not been given a place at our table. Consider, as one example, African Americans. They were also a part of this nation at this time. And as a part of this nation they contributed to its economy, contended for its political integrity, bore arms in its wars, and definitively shaped its intellectual, institutional, culinary, and artistic culture.

And yet, in this new postwar American re-narration, critical truths about African Americans were simply excluded from the story. The dignity of their humanity. The beauty of their cultures. The crime of their abduction. The violence of their subjugation. The darkness of their captivity. The significance of their labour. The sale of their children. The courage of their resistance. The desperation of their flight. The resilience of their communities. The shrewdness of their institutions. The brilliance of their art. The power of their religion. The legitimacy of their demands. The triumphant gorgeousness of their mere survival. Where, one asks, are the monuments to these? In the white nationalist mythology of post–Civil War America, the answer was nowhere.

And not only were these stories not told; they were actively erased. After all, this period of explosive memorialization to the postwar American self-concept is the very same period as the rise of Jim Crow laws in the American South. It is the same period in which anti-black race riots took place in nearly forty cities across the nation. It is the same period in which over four thousand African Americans were lynched. Put most succinctly, at the very moment in which memorials to white conquerors went up, African American communities were torn down.

This violent erasure, this “willed forgetting,” reveals something deeply important about the nature of the postwar American public memory: its aim was not simply to elevate a particular version of the American story; its aim was also to exclude any stories that challenged it, to erase them from public memory.

Resetting the Table

Understanding this context is critical for understanding the conflicts taking place in our communities today. Consider my own city of Charlottesville, Virginia. In August 2017, people around the world watched as torch-bearing white nationalists paraded through our streets, gathered around our memorials, and fought with our residents. And though this was, perhaps, the most violent and notorious expression of this conflict in recent memory, it was by no means the only one.

Indeed, in communities across the nation, the painful struggle over which stories are to be told and how they are to be told endures. It is critical to understand that these conflicts are not fundamentally conflicts over the fate of statues. They are conflicts over public memory; manifestations of a deep and serious struggle over which stories deserve places of honour at our common table and which stories do not. And it is, as it always has been, a struggle that has profound consequences for the shape of our life together.

That this is so gives rise to important questions: How are we, in our own communities, to enter into a conflict weighted with such enormous personal and social consequence? How ought we go about resetting the table of our public memory?

In asking these questions, I am aware of a certain danger—namely, the temptation to control. This danger is hardly abstract. One of the most fraught dimensions of our public life is the way in which, historically speaking, conversations about public ethics, especially with respect to race, are often demonstrably deployed as a form of social control. That is to say, normative conversations about how “we” “ought” to do this or that can—and often do—contain barely concealed intentions to discredit dissent and sanctify the status quo. One thinks, for example, of the ways in which appeals to “order” were consistently deployed as moral pretexts for demonizing the nonviolent protests of the civil rights movement and sustaining the segregated social order of Jim Crow. In like manner, it is more than tempting for conversations regarding how “we” “ought” to carry out the work of public memory to be perniciously used—across the cultural spectrum—as little more than a discursive grasp for preemptive control of both the process and the outcome of our public memory.

Image: March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Public domain.

Image: March on Washington banner. Public domain.

Even so, the ethical questions remain, and we must face them: How ought we go about resetting the table of our public memory? What will this work require of us who seek not simply the telling of stories but—through them—the healing of communities? Is there a way to take up the painful work of recreating our public memory that also nurtures the conditions of public peace?

Is there a way to take up the painful work of recreating our public memory that also nurtures the conditions of public peace?

Though it may seem counterintuitive to the work of social healing, it is—not least in the interest of that healing—critical to acknowledge that there is an inescapably deconstructive dimension to this work. This is because part of the task of nurturing anything approximating a truthful public memory will require both the exposure and the extraction of lies. And while extraction has peace as its aim, it is also inevitably conflictual. Indeed, more and more of our communities have become embroiled in deep conflict over the way this deconstructive work is shaping corporate practices, school curricula, and public landscapes.

This deconstructive impulse is perhaps most prominently seen in the work of those who seek to remove Confederate memorials from public places of honour in order to create space for an alternative public memory. Charlottesville, for example, took this path in removing four prominent memorials in the summer of 2021. And cities such as Richmond, Memphis, and New Orleans have done the same. But deconstruction is also unquestionably at play in those who, in the name of patriotism, seek to discredit and dispense with any alternative forms of public memory in hopes of re-inscribing the carefully curated fables of postwar America on the memories of generations to come.

For my part (Confederate descendant though I am), given the racially polemical context of the emergence of these memorials, the harrowingly deceptive character of their substance, and the malignant consequences of their endurance, I am in unambiguous agreement with those who believe that the memorials ought to be removed from public places of honour. Some, of course, see this as the revision of history. I do not. I see it as waking from an evil dream.

But more important than this deconstruction is the work of construction, work focused not simply on challenging the stories that have been given but on recovering the stories that have been withheld. This, in the end, is what the healing of our public memory will require: not simply the forsaking of falsehood but the deliberate embrace of truth. It will require resetting the table with different stories. But what are these stories, and what will be required of us as we seek to tell them?

In reflecting on this twofold question in the context of my own professional work in public memory, I have come to believe that it is best answered not by constructing a complex theory of memorialization but by embracing the very simple lesson taught nightly at my father’s table. That lesson, simply put, was this: If we are to heal our memories—private or public—we must prioritize the stories of the forsaken.

I realize that the simplicity of this answer, at least on its surface, allows room for the emergence of a certain concern—namely, that this approach, in its deliberate centring of particular stories, simply repeats the imbalanced patterns of the past and, as a result, runs the risk of inflicting the unjust harm of erasure on those who are white. And while, as a white man, I understand both the substance and the spirit of this concern, it nonetheless seems to me to misunderstand the problem we are seeking to address.

When considering the alleged imbalance of the approach, it is critical to remember that, culturally and historically speaking, we are not starting from a neutral place seeking balance. We are, to the contrary, starting from a wounded place and seeking healing. The simple fact of the matter is that the historic practices of public memory in the United States were undertaken with the explicit intent of enshrining a vision of white, male, Christian conquest as a national self-concept, and correlatively erasing the stories of those who called that self-concept into question. And the impact of these practices has been, and indeed remains, the valorization of ignorance and the violent erasure of dissent. Seen from this perspective, the call to centre the stories of the marginal is not a call to retribution. It is, rather, a call to redress.

But what of the concern that the call to centre the marginal inevitably harms those who are white? This is a long-standing concern in historically white communities in times of racial struggle, one that has returned with apocalyptic vigour in our present moment. And while many things could be said in this regard, two things seem to be particularly necessary.

First, it is critical to remember that what is in view here is not the erasure of white stories but the deliberate and active work of telling the stories of others, stories that have not been told. It is true, as I noted above, that there must be the deconstruction of lies. But the deconstruction of white stories is neither the primary work nor the ultimate goal. The goal, rather, is contextualization: situating those stories in relationship to the equally important stories of others. This is what America has never quite been able to do. And it is what must be done.

There are those who will describe this as a new and pernicious form of marginalizing white stories. But it is not. It is, rather, the work of de-centring white stories. And being de-centred and being marginalized are not the same thing.

Second, I believe that a strong case can be made that such de-centring, rather than harming white Americans, is actually the sine qua non for our healing. After all, it was the wilful centring of ourselves through the suppression of the stories of others that poisoned our public memory and that continues to do so to this day. And it will therefore only be through the collective work of seeking these stories out, gathering them in, and seating them at the table of our common life that we will be healed. From this perspective, the call to centre the stories of the forsaken is not in any way punitive. It is, rather, pedagogical.

For these reasons, I unreservedly believe that the work of healing our public memory must begin with the deliberate work of centring the stories of the forsaken. Indeed, I believe that this work—as it is initiated locally, conceived collaboratively, pursued charitably, and expressed creatively—is one of the most important horizons of the labour toward racial justice in our time, one that holds singular promise for the transformation not only of our own lives but also of the lives of generations to come. Though it would pain my teenage self to admit it, Bruce was even more right than he knew.

A Table of Welcome

And yet, in spite of this promise, the work of pursuing a just public memory remains largely underdeveloped conceptually and under-coordinated practically. What might it look like for each of us—especially those of us who are committed to creating a table of welcome in our communities—to take up this work of healing our public memory through the recovery of forsaken stories? Happily, there are currently a number of important initiatives devoted to answering this question—initiatives that embody, in an exemplary way, what it means to centre the stories of the forsaken in ways that nurture the possibility of healing.

As national examples, one could look to institutions such as the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC (2016), the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund (2017), the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama (2018), the Emmett Till Memory Project (2019), the Andrew Mellon Foundation’s $250 million Monuments Project (2020) and the International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina (2022), as illustrations of the possibilities of this work. In like manner, though on a more modest scale, my own work with Voices Underground to build the National Memorial to the Underground Railroad outside Philadelphia is itself inspired by and built on these initiatives.

There are more local, perhaps more accessible, examples too. In communities across the nation, local artists, educators, activists, curators, politicians, and philanthropists are collaborating in the work of more truly narrating their own communities. In this respect, one could think of the work of Brandan “BMike” Odums and his extraordinary work through Studio BE in New Orleans. Or one could think of Anasa Troutman and her work to promote both the story and the legacy of the 1968 sanitation workers through Historic Clayborn Temple in Memphis. Or, to come full circle to Charlottesville, one could think of the work of Dr. Andrea Douglas and her team at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center. In early December of 2021, it was announced that the statue of Robert E. Lee that stood at the centre of the violence of August 2017 will be turned over to her organization. Her plan, in a project called Swords into Plowshares, is to melt the statue down and, after a period of community engagement, to use the metal in the creation of new—more truthful—works of public art. These are just a few examples of what it might mean for us, in our local communities, to take up this work.

But, perhaps more accessible still, one could look—as I do—to a small table in South Carolina. To a delightfully ornery man with a towel on his shoulder, a cigarette in his hand, and a glint in his eye. A man who had the wisdom to set that table with the stories of the forgotten. And who, through his own story, invited me, and now invites us all, to do the same. Why? Because it is here, in the willed cultivation of a welcoming table in our homes and in our cities, that we will heal not only our memories but also our futures.