G

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) and, more specifically, large language models (LLMs) have been the subject of an enormous amount of critical and ethical reflection ever since OpenAI released ChatGPT into the wilds of the internet. Most of those reflections, however, have been about data privacy, the ethics (or feasibility) of replacing human workers with AI bots, or questions concerning what AIs are capable of achieving: Will an LLM attain “general intelligence” or simply plateau, becoming nothing more than a bloated, online ouroboros? Indeed, some thoughtful people have noted the discrepancy between the measurable improvements resulting from AI on the one hand and the hype of what their progenitors promise to investors on the other.

Others have considered the very real possibility of potential degenerative effects on our writing skills if we offload that work to a machine. Of course, defenders of LLMs have a ready rejoinder to these concerns: Socrates worried that we would lose the art of memorization with the advent of writing. Do the virtues of being able to orate entire sections of the Odyssey, they might ask, really outweigh our making it universally accessible to all literate people? Surely our common gains outweigh those particular losses—indeed, technology in this case appears to universalize and democratize the gains, while the losses are only to particularly talented individuals.

But what if the creation of language and its communication are fundamentally different from what LLMs are doing? What if language use is not just one more skill among many? What if LLMs are subtly altering how we communicate with one another and approach reality more generally? What if the dazzle of what LLMs produce is masking from us the ways in which these changes may be beginning to occur? And what if the purported gains and losses will in fact be the reverse of what developers and investors are forecasting—that is, what if the downsides are universalized and democratized while only a select handful of highly talented people will be able to resist them?

Three lines of psychology research from the latter half of the twentieth century suggest that an uncritical adoption of LLMs might set us on track to lose something unique in our humanity.

In the middle of the last century, Burrhus Frederic Skinner (known more widely by his initials, B.F.) was the public face of “behaviourism.” In its founding, behaviourism, a subfield of psychology, argued that all truly scientific variables must be externally observable, and therefore any analyses of internal mental “dynamics” (such as those proposed by Sigmund Freud) are mere superstitions masquerading as science.

More specifically, Skinner and others argued that all discernable patterns of behaviour are the result of reinforcement dynamics. All animals are interested in maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain. Therefore, if you want an animal to do something, create a pleasurable association with that behaviour using a reward. Televised examples of behaviourist successes in training rats, pigeons, and even human children demonstrated the utility of this model for shaping behaviour. Therapeutic institutions, parenting, corrections—all began to apply “scientific” behaviourist principles. Physical science had just defeated the ideologies of the past, and now psychological science would shape the future—behaviourism was riding high.

Given the success of applying behaviourist principles to more and more kinds of behaviour, Skinner made an ambitious turn to explaining human language and thought. In 1957, he published one of his most comprehensive works, Verbal Behavior. In this book, he argued that language acquisition among children is the result of a conditioning process: children randomly emit sounds in the form of words and sentences, and parents reinforce certain sounds and discourage or correct others. To anyone who has interacted with children during their period of language acquisition, this may sound like a plausible account of the process, but it contained a fatal flaw.

A linguist named Noam Chomsky publicly took issue with Skinner’s view. Chomsky argued that children acquire language far too rapidly for the process to take place according to this incremental, word-and-reinforcement exchange built on behaviourist principles. Arguing from a position that he came to refer to in 1980 as the “poverty of the stimulus,” Chomsky pointed out that children say far more than they directly hear during childhood, and they frequently use different combinations of words and phrases to construct entirely novel sentences without the need for reinforcement. Indeed, children produce speech that they’ve never heard before, and which has certainly never been reinforced—“I hate you, Mommy,” for instance. If the behaviourists were right, such sentences would almost never be uttered.

There are still many mysteries around the human acquisition and use of language. However, almost fifty years ago now, it was demonstrated that human children do not simply imitate words and sentences that they hear, gradually building vocabularies and internalizing grammars following correction and reinforcement from adults. In short, it is not possible to account for human language acquisition using behaviourist principles alone.

Fast-forward forty-two years, and OpenAI releases ChatGPT. Human children don’t learn language through a fully behaviourist process, but Silicon Valley bet that a machine could. Unlike the fairly limited amount of language human children are exposed to during their acquisition period, LLMs are programmed to apply behaviourist principles to a massive amount of verbal behaviour thanks to the internet. As a result, we see a convincing facsimile of human language acquisition among LLMs, but it is important to understand—given Chomsky’s observation—that it is a facsimile: the way LLMs “learn” and “speak” is fundamentally different from the way humans do.

This may seem like a distinction without a difference since LLMs appear to learn and use language correctly. Don’t they pass the Turing test, after all? However, OpenAI doesn’t represent the first time in history that someone has tried to “teach” language to non-humans using behaviourist principles.

Following Chomsky’s takedown of Skinner’s theory of language acquisition, some psychologists were determined to nevertheless show that Chomsky was wrong about one implication of his argument: that language is fundamentally unique to humans. This led to a wave of researchers attempting to teach language to non-human primates in the 1960s and 1970s.

These simian language enthusiasts argued that the only reason non-human animals didn’t acquire language like ours was due to an underdeveloped vocal apparatus, and that American Sign Language would offer the opportunity for non-human primates to acquire and use language on par with humans. Perhaps the most prominent example of an attempt to do exactly this was Koko the gorilla, who ultimately appeared in a charming episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood in the 1990s, signing effectively to its eponymous host.

These apparent successes, however, hit a qualitative plateau. While the primates were able to acquire hand gestures and use those signs to effectively represent relevant objects in their environment, their non-verbal signs seemed to be entirely instrumental in character. For example, the primates would sign “banana” if they wanted a banana—a very real achievement, to be sure—but they would never sign “banana” to just talk about bananas or get a shared sense of what bananas really are. In fact, there was no systematic evidence that they talked about anything for the sake of sharing an experience about that thing with someone else—something that human children (and adults!) do almost constantly. Relatedly, they never seemed to recombine learned symbols to produce novel sentences or words, with the aim of using language to make sense of discoveries about reality.

There was some anecdotal evidence that they could do this. Some trainers who worked with gorillas and chimpanzees claimed that they had observed non-human primates engaging in just such creative combinations in order to share an inner experience about something with a human conversationalist. One reported example involved a chimpanzee named Washoe, who, on a lovely canoe ride with one of his trainers, saw a swan. His trainer claimed that upon seeing the swan, Washoe made the sign for “water” and the sign for “bird” in order to designate what he saw as a “water bird” and share that experience with his trainer. If true, this was evidence that non-humans could, at least in theory, use language the way humans do.

LLMs are trained to produce language using behaviourist principles—just like the non-human primates who attained an impressive level of nonverbal linguistic ability—in order to imitate human language use in “conversation” with their users.

But these were just random reports and anecdotes; no systematic proof of these abilities existed. The weight of that proof fell on the shoulders of a chimpanzee named Nim Chimpsky (a not-so-subtle dig). “Project Nim”—as this chimpanzee’s language-acquisition project eventually became called—was aimed at producing the systematic evidence of simian language use that others had not. And indeed, the project’s researchers thought they were succeeding: Nim seemed to use language in a way that humans did, combining signs in order to share an experience about things with no instrumental goals in sight. Put another way, Nim appeared to be having “water bird” moments like Washoe all the time, and these human-like interactions were recorded as proof.

However, in preparing the results of this work for publication, Herbert Terrace (a psychologist involved with the project) reviewed the video tapes of the experiments and noticed something that no one had before. In those “water bird” interactions, the trainer who was acting as a conversation partner was subtly (and probably unconsciously) signing the desired sign just a split-second before Nim. It turns out Nim wasn’t initiating a signed conversation about an object to share with his trainers; he was imitating signs that his trainers had unconsciously initiated. The reason Nim made those signs was that he had been trained to do it—during his training, according to behaviourist principles, he had learned that imitating human signs correctly would result in a reward. Nim, it turned out, wasn’t using language in a declarative, human way; he was merely imitating it to get rewarded.

It was concluded on this evidence that Koko, Washoe, Nim, and other non-human primates like them were responding to instrumental demands of their conversation partners—not engaging in communication per se. Their imitations made it seem to the conversation partner that they were having a signed conversation about something. But in reality they were merely producing the results of their conditioning. It turns out there were no water birds; there were only bananas.

LLMs are trained to produce language using behaviourist principles—just like the non-human primates who attained an impressive level of nonverbal linguistic ability—in order to imitate human language use in “conversation” with their users. I could simply end here, noting that no matter how impressive these LLMs become, since they acquire language through imitation and reinforcement, they will, in principle, only ever use language in response to invisible reinforcement mechanisms that have been employed in the design or training of the LLMs. What’s more, any appearance of “general intelligence” in LLMs is exactly that—an appearance, one might even call it an illusion—just as the supposed human-like language use among non-human primates was nothing but simian simulacra.

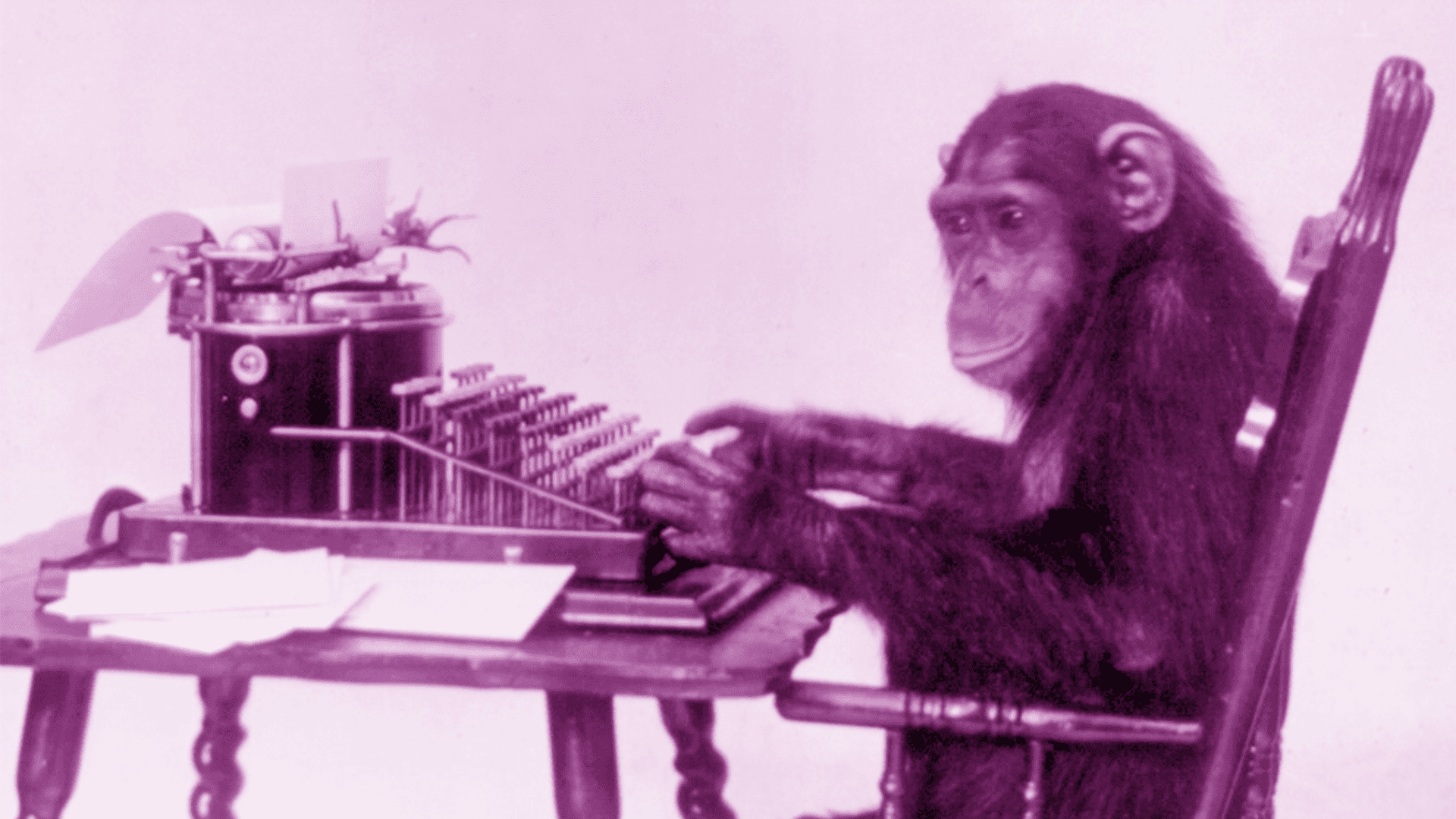

Yet there is a substantial difference between non-human machines and non-human animals. While a chimpanzee typing at random with an infinite amount of time may happen to produce the complete works of Shakespeare, no one is tempted to use a chimpanzee as a means of generating an email to a friend, or the text for a presentation, or the content of an HR memo for employees; but many people have used LLMs to produce those things. How might such widespread use affect us in the long run? To find out, we first need to understand communication’s role in establishing reality and building trust in relationships, and to do that we must return once more to the twentieth century.

In a study first conducted in the 1970s, E. Tory Higgins and William Rholes demonstrated what they called the “saying-is-believing effect.” In this study, participants were given neutral information about a person—in the most recent versions of this study, the person’s name is Michael—and then they were asked to play a game with a communication partner. In this game, they were told they needed to write a short description of Michael for their conversation partner to see whether that partner could correctly identify Michael. They were told that the conversation partner knows Michael—and also told that this person doesn’t particularly like him. (Half were told that the person did like Michael, but since the effects were the same, let’s just focus on the negative for simplicity’s sake.) Participants then wrote a short description of Michael using the information they were given about him, except they tended to shift that information to make it negative, so that their conversation partner would know whom they were talking about.

For example, maybe the participant was told, “Once Michael makes up his mind to do something, it’s as good as done, regardless of how difficult it is. Only rarely does Michael change his mind even when it might well be better if he did.” The material is evaluatively ambiguous—is Michael persistent or stubborn? In this study, participants generally tuned their description to the audience, so if told that their communication partner doesn’t like Michael, the communication emphasized how stubborn he is.

After writing this communication, participants gave it to the experimenters, who claimed to pass it to their partner. After some time passed, the experimenter came back to tell them that their communication partner (who, as the reader is likely suspecting, didn’t really exist) correctly identified Michael as the target of the description. Then the experimenter asked the participants to recall the information they were given about Michael. Intriguingly, they didn’t recall the original, ambiguous information; they recalled instead the negative information they produced in their communication—Michael is stubborn, full stop. Perhaps even more intriguingly, if they were told by the experimenter that the communication partner failed to identify Michael, the reverse happened: they recalled the original, ambiguous behavioural information, not the negative version from their communication. Participants, in other words, recalled the information about Michael that they judged most likely to be true: If their negative communication was confirmed as accurate through recognition by someone who supposedly knew Michael, then it must be the truth. If not, then the best information they had about Michael was the ambiguous information they got at the outset of the experiment.

Or maybe this result was just another behaviourist artifact, where the social verification acted as a reinforcement for the communication, rather than being about truth per se. Maybe the positive or negative feedback is just telling participants which version of a communication is preferred, regardless of where the truth lies (like feedback given to an LLM). One way to test this is to alter why the participants were communicating. If the saying-is-believing effect is just a matter of reinforcement, then the audience’s social verification should reinforce the communication regardless of the motivation behind that communication. If humans are just like LLMs, then positive verification following communication should influence memory regardless of the intent of that communication.

To test this, in a series of experiments in the early twenty-first century, researchers tried versions of the saying-is-believing paradigm where the reason for communicating was instrumentalized. In one version, rather than trying to get the audience to correctly guess that the person they’re talking about is Michael, participants were told that if they wrote a message congruent with the audience’s perception of Michael, they would get a monetary reward. In another version, they were asked to create a version of the communication in which Michael’s traits were wildly and hilariously exaggerated in a manner congruent with the audience’s point of view in order to entertain themselves. In other words, in these alternative versions of the experiment, participants were asked to subordinate their motivation for accuracy to something else. Instead of using language to communicate, they were asked to use it to entertain themselves or to obtain a material reward.

In both cases, the effect failed. Was this because there was inadequate behavioural reinforcement? Quite the opposite. Participants received social verification, just like in the original version, and in these versions they also got money or entertainment to boot. Instead, the reason participants didn’t recall their communication was that they knew it wasn’t true. Working to create language that bears the burden of truth is a unique and indispensable component of human social life.

The results from these experiments led the researchers to propose the theory of shared reality. Building on all of the work surrounding how linguistic communication works in humans, they proposed that we use language intersubjectively in order to understand the way the world actually is: what we believe is bound up with how we relate to one another, and language is a major force linking the two in human psychology. A child might call a swan a “water bird” and then look at her mother for confirmation—not for any instrumental reward like bananas, but because she really wants to know the right word to use to refer to the swan. We are sharing animals, and we most prominently share through language—this is why humans are so positively weird when it comes to acquiring language, why this particular use of it is so unique to us, and, ultimately, why we so desperately need to jealously guard this aspect of our social lives from being replaced by machines.

LLMs, since they are designed and trained using behaviourist principles that rely on reinforcement, have an almost invisible instrumental component to their communication. They are aiming at what they have been trained to produce, and they produce it very well: language compiled in a way that is satisfying to the user. The text is completely empty of any attempt to approximate reality, and it certainly is devoid of any motivation to communicate.

All use of text produced by LLMs will necessarily carry with it this instrumental limitation, because the very act of using LLMs recasts language from its uniquely human purpose of discovering the truth about things and instead subordinates it to the purposes underlying LLMs. The most obvious case is the college student who chooses not to do the class readings and provides a ChatGPT-generated paper summarizing those readings to get a passable grade. The student doesn’t care about the readings or whether the paper reflects his knowledge—in short, the student doesn’t care about how language can describe something true; he only cares about how language can be useful. His words become specious—outwardly pleasing but having no relation to reality.

Now imagine some future iteration of LLMs that writes emails, designs presentations, constructs text messages, perhaps even imitates our voice and makes phone calls on our behalf. Perhaps in each of these instances we really want to communicate with our partner, friend, or audience. But the LLM pops up in the corner as we begin to write and promises to make it “better”—write the email in a manner that is more influential, make the text message more entertaining, improve the presentation to land the promotion—and do so while increasing efficiency, letting us use the time for some other purpose. Instead of communicating—using language to deliver our best approximation of reality as we understand it in order to share it and to learn from our communication partners—our text or presentation or email will now carry with it an instrumental purpose to please or entertain or obtain some material end. As LLMs integrate with more text-generating applications and their use becomes more and more frequent, our textual exchange will become less and less human, and more and more like a non-human animal (or, worse, a non-human machine) shaped by behaviourist principles. After over sixty-five years, Skinner will have the last laugh.

What we believe is bound up with how we relate to one another, and language is a major force linking the two in human psychology.

What would becoming less human in our textual exchange mean? The research highlighted above suggests that we would become more detached from reality and from one another; shared–reality theory argues that our motive to establish what is real is bound up with our motive to relate well with others. Trust would decrease. After all, everyone would be speaking in text with an ulterior instrumental motive—a motive perhaps invisible even to the speakers themselves. As a result, we would become both worse at discerning truth from falsehood and more socially isolated. Further, in the words of Charles Taylor, “Without any articulation at all, we would lose all contact with the good. . . . We would cease to be human.”

It should not be surprising to the religious among us—particularly Christians—that this would be the case. The heart of our liturgical worship and preaching is based on the written Word of God. Furthermore, the authority of these Scriptures is derived from the authority of the Son—God as he has chosen to reveal himself to us in his Word. And it was precisely that person of the Trinity who took human nature into himself to carry it back into eternal communion with the Father and the Holy Spirit. There is something fundamental and essential to our humanity that is bound up with our use of language as a form of communication with one another. Its loss may therefore not only degrade our ability to speak the truth but even cripple our capacity to speak the truth in love.

Despite these concerns about LLMs, there are clearly ways in which AI can act (and has acted already) as a supplement to human ingenuity and curiosity and our shared pursuit of the truth. AI has made several medical advances possible, and personally I no longer intend to write all my R or Python scripts from scratch. (Even so, the aspirational predictions of AI’s professional boosters are almost certainly overstated.) We must resist the temptation to replace actual, effortful communication with easily generated text designed to manipulate, dominate, and titillate our audiences. We must resist the behaviourist encroachment into this uniquely human aspect of our social life.

It is not obvious how best to enact such resistance. In many ways, it wouldn’t be so problematic if we weren’t already so psychologically crippled by smartphones and social media—a problem that will get far worse if we widely adopt LLMs to replace our personally generated communications. There may not be a legislative solution on hand in the short term. Silicon Valley appears to be the only constituency that has substantial pull with both political parties. Instead, resistance might have to become a rule of personal, familial, and ecclesiastical life, a new digital monasticism.

What might digital monasticism look like? I’ve suggested above that the widespread use of LLMs will lead us to become less human; it should come as no surprise that the historic church has resources that can accomplish the reverse. The traditional monastic vows mirror the church’s evangelical counsels of perfection: poverty, chastity, and obedience. The practice of each of these principles with respect to our digital lives may be the only way to reliably stave off the worst effects of LLMs and smart devices more generally.

Some may dismiss such recommendations as unrealistic or extreme, but these principles are already being put into practice by the next generation. With respect to poverty, in spite of the way that Silicon Valley has convinced many of us that we “need” our smartphones (and will no doubt convince many that we “need” our LLM “companions”), some young people are ditching their smartphones in favour of “dumb” or “flip” phones. Similarly, with respect to chastity, there are pockets of resistance to the ways that the ubiquitous use of smartphones (and, importantly, social media) have changed our psychology for the worse. Both stand as worthwhile advances that will make human flourishing a goal easier to grasp.

Perhaps the most important principle, however, will be obedience. Obedience is sometimes misunderstood as the acquiescence of the powerless to the force of will exerted by the powerful, but this construal misses the etymological root of obedience—the Latin oboedire—which literally means “listen to.” When we “listen to”—when we are obedient to—LLMs, we are ultimately listening to ourselves (a point Shannon Vallor makes in The AI Mirror). A world flattened by LLMs will be a world in which everyone believes what is right in their own eyes. A world shaped by digital monasticism will be one in which we listen to one another in order that we ultimately believe what is true. “The natural habitat of truth is found in interpersonal communication,” as Josef Pieper wrote.

This is the final inversion of what the boosters of LLMs promise. Their future is one in which we are equipped to instrumentalize communication in order to get what we want. However, according to the witness to these principles of perfection that we find in the life of Jesus, the path to living as true human beings will be a path of obedience—one in which we give and receive our words, gently and lovingly coming to one mind with respect to what is true. Each of us stands at a crossroads between these two paths, and the shape of our lives, our families, and our churches may very well be determined by which path we choose to tread.