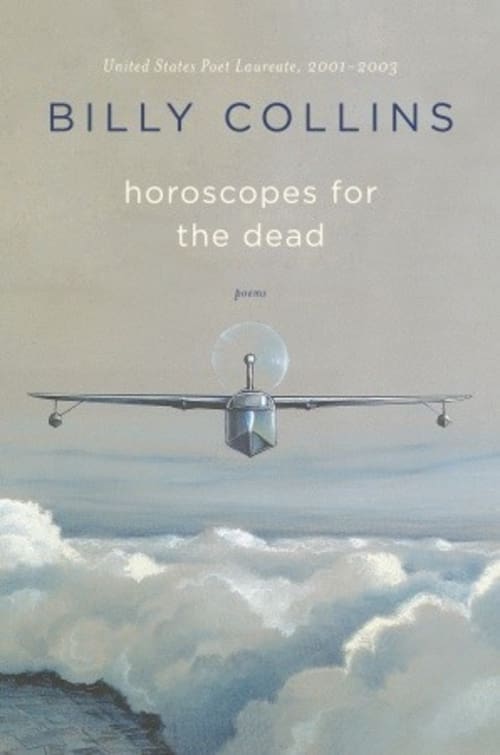

Horoscopes for the Dead: Poems by Billy Collins. Random House, 2011. 128pp.

He considers the boulevards ideal for thinking,

so he takes the air on a weekday evening

to best appreciate the crisis of modern life.I thought I would try this for a while,

but instead of being in Paris, I was in Florida,

so the time-honored sights were not available to me

despite my regimen of aimless strolling—

(“The Flâneur”)

There’s something charming about a man who calmly describes an absurd thing he has done or seen and then, as he continues to talk, gently lifts his listeners into a sense of larger purpose—a moral, a lesson. The speaker’s premise may seem artificial, as may his transition and conclusion, but the appearance of artifice is part of his speech’s delight. And theatrical comedy has always been an effective foil for the tragic, the more meaningful.

Billy Collins is such a man. He sashays into Big Ideas with apparent ease, poem after poem—death, love, the self, the death of love, love of the self. Beginning with the impossible or the mundane he transforms the conversation, like a witty party guest, into larger questions: Who am I? Why am I here? What is history? What will happen after I die? Collins, for all his critical disparagement (“very bad . . . working in a quasi-high culture mode,” wrote Paul Stephens in Drunken Boat ten years ago) and popular acceptance (he’s sold over 200,000 books), is a poet of worldviews. The lightly absurdist, neo-metaphysical approach he has mastered suits this purpose well.

Collins’s subject matter is always a bit outlandish. In Horoscopes for the Dead‘s first poem, “Grave,” he speaks to his parents in their graves; only his mother replies. In “The Snag” he pictures himself going back in time to murder his maternal grandfather, the source of his own baldness. Realizing that that might interfere with his own existence (“not to mention the possible existence of my mother”), he decides that, if he really could go back in time, he would drink whiskey with the old man and then request to sit in his lap. Within an impossible hypothetical, Collins posits a plausible choice. Sometimes he reverses the effect, positing an impossible hypothetical in a realistic context. “Hell,” in which he draws out an analogy between The Inferno and “shopping for a mattress at a mall,” concludes with an image of Dante himself trying out one of the mattresses.

His conceits are also extended, sometimes for pages, no matter how apparently insane. Collins’s hand forming “the head of a duck” occupies centre stage in “Silhouette.” Not even casting a shadow, this duck is outdoors, “a wrist for a neck / and fingers for a beak that never stops flapping, / jabbering about some duck topic” until the poet turns it to face him: “Then he stops his quacking / and listens to what I have to say, / even cocking his head like a dog / that listens all day to his master speaking.” After three pages and 52 lines of conjecture on this fanciful topic, Collins puts the hand-duck in his pocket where it “continues its agitated talk.” The first two lines of this poem recognize a larger context: “There is a kind of sweet pointlessness / that can visit at any time.” And at the end of the poem, it’s Collins’s birthday. The duck becomes a metaphor for the brief silliness of human existence—in this case, the poet’s own.

I’ve always liked Billy Collins. I’ve wanted to tell the world that he’s a metaphysical poet, a child of the 17th century. I’ve wanted to say to his critics: Stop judging him according to modernist standards; he’s not doing the modernist thing. He’s not even really a postmodernist, as I’ve heard him called, but rather a son of John Donne and Andrew Marvell: witty, socially hyper-aware, and given to extended analogy. He constantly discusses love, time, and death in terms of the commonplace. The famous metaphysical conceit, as defined by my trusty reference volume, J. A. Cuddon’s Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory, 3rd Ed. (Basil Blackwell, 1991), is marked by a “preoccupation with analogies between macrocosm and microcosm . . . [marked by] wit, ingenuity, dexterous use of colloquial speech, considerable flexibility of rhythm and meter . . . a liking for paradox and dialectical argument, a direct manner, a caustic humour, a keenly felt awareness of mortality, and a distinguished capacity for elliptical thought and tersely compact expression.” Doesn’t that definition perfectly fit Billy Collins?

If there’s a difference, it’s that his expression is not “tersely compact,” but rather breezy and prosaic. The Metaphysicals were rigorous about form, foot by foot, line by chiseled line. Collins goes about verse more like a casual shopper, browsing from item to item, turning each over in his hand to inspect it. His logic doesn’t miss a twist, nor is it ever unclear what he’s saying in his poetry, but his music is not intense. If it were, though, there’s a good chance he wouldn’t be as widely read in the age of fiction. Important to note, fiction as we know it didn’t exist in the 17th century. Literary historians consider Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740) to have been the first novel. So the knock against Collins that his music is weak sauce, its lines replaced by sentences, might be countered by an explanation that he has adapted appropriately to his era. Critics also carped about Walt Whitman’s prosody as grass grown too long and, as they saw it, in desperate need of mowing. An unsigned review in the January, 1882, Atlantic lamented Whitman’s “frequent feebleness of form and style which reduce large portions of [Leaves of Grass] to tedious and helpless prose.” But almost all of Whitman’s contemporary critics regarded their subject as immoral and humourless, too, which I’ve never heard anyone say about Collins (at least not about his poetry).

Enough of “aimless strolling”: what about Collins’s “regimen,” that which makes his poems rigorous enough to stand the test of time? In my opinion it’s his rhetorical turning. The turn, as high school students ought to know, is another established element in poetry. It happens most famously near the end of a sonnet, usually in the ninth line, and is often signalled by a conjunction such as “but” or “and.” It’s also called the volta, which is Italian for “time.” The ninth line of Shakespeare’s “Sonnet XXIX” begins, “Yet in these thoughts.” But turns don’t necessarily happen only once per poem. The penultimate line of that same sonnet begins, “For thy sweet love remembered.” In Collins, as in most thinky poets, turns happen frequently and aren’t always detected upon first reading. Stephen Dunn, another contemporary American poet, says that “drift and counterdrift seem central to the way many of my poems behave. It’s also the way my mind works. I can hardly make a statement without immediately thinking of its opposite.” (Read more of Dunn’s and other poets’ self-analysis in the book Contemporary American Poetry: Behind the Scenes, edited by Ryan Van Cleave; Longman, 2003.)

Collins’s quiet “drift and counterdrift” movement becomes more noticeable when the reader knows about it. It’s one of his poems’ qualities that makes them so (perish the thought) funny and entertaining. Take the poem “Thieves,” for instance, which begins with a stanza of simple observation:

I considered myself lucky to notice

on my walk a mouse ducking like a culprit

into an opening in a stone wall,

a bit of fern draped over his disappearance,

Even in its simplicity this stanza is already doing some work; the opening words introduce the poet’s meditative mood, and the high diction of “a bit of fern draped over his disappearance” provides a platform of irony for what will follow. In these lines, Collins makes no attempt to hide a gesture toward the Romantics, who often walked around in nature noticing things (see Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely As a Cloud”). A conjunction indicates a turn at the beginning of the second stanza:

for I was a fellow thief

having stolen for myself this hour,

lifting the wedge of it from my daily clock

so I could walk up a wooded hillside

and sit for awhile on a rock the size of a car.

Bit of a stretch to figure himself for a “thief” when all he’s stolen is time from his own schedule, but it’s a stretch the reader might be willing to entertain because of the utter appropriateness of the mouse-themed “wedge” (of cheese) and “clock” (as in, “hickory dickory”). But then, jettisoning all tidiness, he compares the boulder he’s sitting on to an automobile. This is the first definite move away from the Romantic language in which the poem is couched. This car symbolizes the “crisis of modern life” he had identified in “The Flâneur.” He amplifies the crisis in the third stanza, which also begins with a turn, this time tonal:

Give us this day our daily clock

I started to chant

as I sat on the hood of this Volkswagen of stone,

and give us our daily blood

and our daily patience and some extra patience

until we cannot stand to live any longer.

In the rhetoric of the Lord’s Prayer, Collins situates a “Volkswagen” and a bit of ennui worthy of Woody Allen: “our daily patience and some extra patience / until we cannot stand to live any longer.” We are far, it feels, from the initial mouse, and the next five lines lift our view to something even larger and more distant, both physically and historically:

And there on that granite automobile,

which once moved along

in the monstrous glacial traffic of the ice age

then came to a halt at last on this very spot,I felt the motion of thought run out to its edges

Which prepares us for another turn, and we will get a sharp and obvious one: “then the counter motion of its / tightening on a thing small as a mouse / caught darting into a wall of fieldstones . . . ” So we return, by counterdrift, to the poem’s central conceit, its overarching metaphor. For what is the mouse a metaphor? Ultimately, through comically dialectical movement, it becomes a metaphor for the poet himself, whose “wee, timorous mind” follows the mouse into the tiny hole and into this very poem: a “shadowy cave” of his own mental making—not (eh-hem) unlike Plato’s cave, it’s one that allows him to see material things in their dynamic relationship to our ideas about things and our words for things.

And “Thieves” is not even my favourite poem in the collection. That honour goes to “Roses,” which, in addition to being sweet, funny, and surprising, contains pitch-perfect lines such as “the ones at the edges turning brown / or fallen already, down on their girlish backs / in the rough beds of turned-over soil,” then goes on to explore the mixed feelings roses must feel about being observed in their final, less-attractive days. Collins makes a cameo in this one as a “stranger staring over the wall, / his hair disheveled, a scarf loose around his neck, / writing in a notebook”—like a mouse, peering.

I suppose it’s just as easy to get caught up in Billy Collins’s poems as it is to dismiss them. That’s high praise for Collins, considering that Whitman had the same divisive effect, and so has the composer Philip Glass (“alluring to some, but as aggravating as a broken record to others,” said The Economist last November). In fact, Collins reminds me a lot of Glass, an expert in cultivated simplicity whose wide popularity flushes out critical prejudice almost immediately. In Horoscopes for the Dead Collins works with the most time-honoured themes of death, love, the self, nature, history, and culture—precisely as the Metaphysical poets 350 years ago did—and, I would say, just as importantly. He is, indeed, a poet of worldviews. Most poets nowadays can’t get away with being so thematic. Collins’s self-deprecating humour and rich understanding of literary history sells it.