The quality of the sunlight in the small town of Tabaka, amid the steep hills of the Kisii region of Kenya, is difficult to convey. The tree-covered hilltops ensure at least a bit of rain every day in the afternoon, and so the trees and the tea plantations vibrate with the luscious green that comes only from frequent downpours followed by intense sunlight. After several weeks of living on one of those hilltops with my wife and children, I have encountered countless rainbows, and I still gape everyday at the dazzling sunsets.

We have no running water, but a trek down the hill to a community source provides us with what we need. Strolling along footpaths with my plastic jug, I greet men walking together, their handmade knives in one hand and half-finished stone carvings in the other. Fingers whitened by stone dust, they scrape away almost without thinking as they walk and chat. Looking down at my feet, I find broken, discarded, and half-finished stone carvings embedded in the path—misshapen hearts, animals, shattered chess pieces randomly amassed like fragmented stories.

In Tabaka, the main business is stone carving, and most of the inhabitants are involved in this trade in one way or another. In those light-bathed hills, you see, there is an almost magical carving stone. Kisii stone, they call it. Multi-coloured like a Tabaka sunset, this stone has stirred awake a dream that had been sleeping in me for nearly seven years.

***

I moved to Africa to work in collaboration with Ten Thousand Villages, a pioneer in the fair-trade industry. My job is to facilitate purchases of carvings for the North American market, and also to see what can be done to foster the skills and improve the lives of these artisans and their families. The work is going well; the goals are being met; my family is enjoying our time here. We have made many friends. But hidden in all of this is also my secret plan, a secret plan for this stone.

I want to carve it. I want to make Holy Icons.

A decade before I had studied to be an artist. A contemporary artist, mind you. I had steeped myself in postmodern theory, Heidegger, Baudrillard, Derrida. I had rented that post-industrial artist studio with friends in a seedy part of Montreal. I had worked to develop my artistic “approach,” my “statement,” my “vision.” I had done the young starving artist bit, though ultimately it had left me in crisis.

As a Christian trying to integrate my faith and my worldview in a postmodern world, and as an evangelical Christian artist hoping to connect my faith with what I was making and why I was making it, I had failed miserably. In trying to create art objects that referred to Christian imagery without irony, I discovered that the art world had no room for what I wanted to explore. Contemporary art was steeped in irony and cynicism, mixed with elitism and a fetishization of the art object. It seemed impossible to make something that was true: not only true in its vision, not only true in its embodiment, but also true in its very purpose. When I finished my bachelor’s of fine art in painting and drawing, I had the highest grades in my class, yet my professor still took me aside on my last evaluation to tell me that I “didn’t belong here” and should go to seminary instead.

So I fled the world of contemporary art, abandoning the studio and destroying my paintings, telling myself and my new wife that I was done with art. I would just be a normal guy with a job and that was fine with me.

She laughed off my grandiose decision, saying I would inevitably return to art. I was annoyed by her dismissal. But of course, in the end, she was right.

***

The Kisii stone immediately seduced me. Cool and resistant like any stone, but velvet soft to the touch—not hard like marble or granite, not gritty like limestone or sandstone. It is a kind of soapstone, I was told: steatite. Its strong concentration of talc makes it different from the dark, speckled soapstone carved by Indigenous peoples in Canada. In Kisii stone, liquid colours ranging from yellow to pink to purple run over a mostly creamy, greenish-white backdrop, sometimes subtle, sometimes with bold flashes or streaks.

By the time I arrived in Kisii, I had already been working with African artisans for six years. I had met and accompanied many carvers: Sitting among young men hacking away at a piece of mango tree with an adze in the sweltering heat of Kinshasa; discovering on the island of Lamu those ancient Islamic carvers who engraved mysterious patterns into mahogany door lintels; wandering though the large Kamba cooperatives on the coast of Kenya, where hundreds of woodcarvers sat together in mountains of woodchips making the giraffes and elephants bought by tourists. This stone though, these carvers, arriving as they did on my horizon in the last year of my African sojourn, were different. This Kisii stone was calling me.

***

In my days as a contemporary artist, I almost disdained materials. In school I had avoided sculpture, and I found even oil painting too complicated and demanding. My vision, my ideas about image making—those were what drove my art production, and I had to make sure materials did not get in the way too much.

This mental approach to art, just like to religion, crippled me. I entered into a crisis of both art and faith. Just as there had been for me a profound rift between the possibilities of contemporary art and an embodied faith, so too my very faith now seemed like a veneer of arbitrary belief over a materialist world.

A search for connection led me into a desert of strange and forbidden texts. I found myself rubbing elbows with heretics and pagans, occultists and secret societies who promised esoteric knowledge, all in a desire to connect with a deeper, more integrated spiritual reality.

Thanks be to God, in my groping and searching I also discovered the church fathers—those great mystics like St. Gregory of Nyssa and St. Maximus the Confessor. They offered an alternative to the strange alienation I experienced: an integrated vision of the cosmos, where things exist as particular identities and these particulars are united to the infinite through the incarnate Christ. This metaphysical pattern was in Scripture all along, but had been veiled from me until then. The powerful cosmic image of Christ presented by these luminaries opened up a world of divine immanence and theosis.

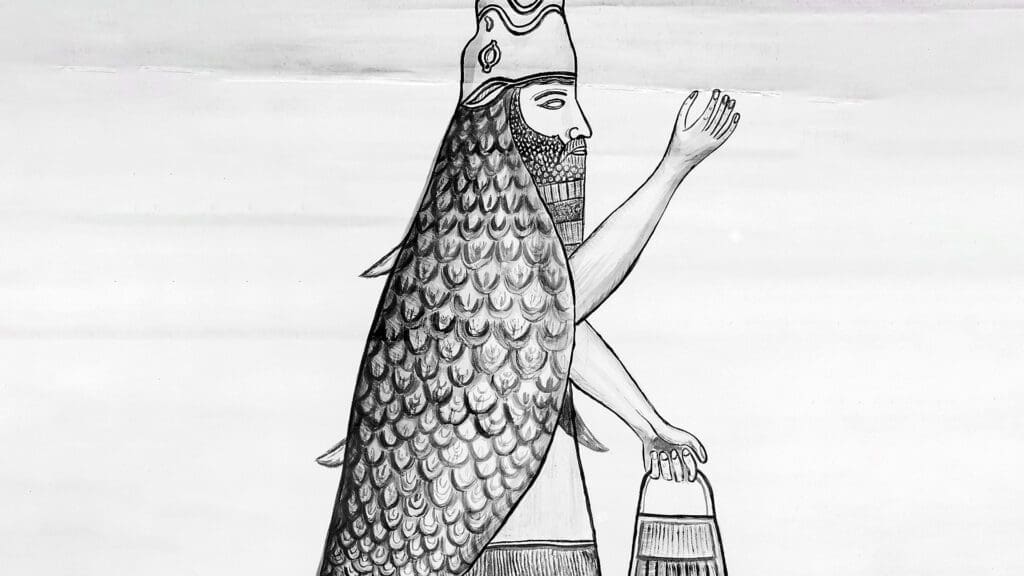

It also opened up for me the wonders of ancient Christian art, which embodied, visually and spatially, the cosmic pattern of Christ. A universal algebra of sacred images had developed, references and codes that brought together space and time, past and future, not only in images but also in architecture, and not only in space but also in the rhythms of liturgical celebration. I had found a grand sacred language, a cosmic dance culminating with Christ as Lord, the head of this great body.

Like my Kisii stone would call me many years later, this language beckoned. Or rather, it commanded that I join the dance. Here, in this great art synthesis, I had found a proposition that was true.

As an Orthodox catechumen, I spent endless days in university libraries, poring over piles of books on ancient iconography, frescoes, mosaics, and illumined manuscripts. I photocopied, tagged, and classified hundreds of pages by theme, before going online in the burgeoning days of the internet to do more of the same. I wanted to cleanse my mind, to reshape my web of references.

It was working. But it was still a very mental exercise, one that, though necessary, also needed to be wed to matter. I found within myself a growing desire to participate in the arts of the church.

***

I had said I was done with art, yet now, in this new discovery of tradition, I desperately wanted to paint icons. But in those days it was almost impossible to find a teacher, and it did not seem reasonable to improvise.

One day my parents asked me if I wanted some pieces of a linden tree they had cut down in their yard. They had seen somewhere that this wood was good for carving. “I could make a cross,” I thought to myself. “Yes, I could carve a crucifix.” With no tools except a few X-Acto knives, I proceeded to carve a cross somewhat frenetically, sitting on the kitchen floor.

It was painful, and awkward, and frustrating. But love, it seems, covers a multitude of sins. The reality of the body and how it relates to art was made clearer to me in that experience. I discovered a different world of making, one where mastery requires discipline. Art is not only about ideas and desire; matter must be understood and encountered appropriately, or else it will resist you. Clarity of purpose, clarity of pattern, and a proper disposition are necessary. But so too are the proper tools, space, and materials. All of these must be united in order to experience the joining of heaven and earth that constitutes any successful artistic endeavour.

***

My next carved icon was much better, but it would not go any further. In all this swirling of activity and crisis, my wife and I accepted volunteer positions to work with artisans in Africa. Off we went, first to live in Congo for four years and then in Kenya for three more. I thought it would be wonderful, an opportunity to access exotic African woods. I would carve icons in my spare time. It would be great.

It was great, but I did not carve a single thing, not for six years. I kept my little woodcarving tool kit with me while in Congo. I thought about carving. But I did not carve.

I worked with dozens of woodcarvers. I designed new products with them. I studied Congolese tribal art, categorized ancient geometric patterns, and even curated an art show of masks and musical objects with the National Museum of Congo. I met some of the most engaged and dedicated artisans you can imagine. But I did not carve.

I can explain it: too busy, too wide-eyed from culture shock, too exhausted by the tension of postwar Kinshasa. We also had two of our children, went through civil wars, survived fraught elections.

The meeting of heaven and earth requires the proper place and the proper disposition, and the kairos moment—that joining of opportunity, intention, and will—simply did not manifest itself.

I can explain it, but I also know that there was something else going on. In jumping into the difficult and gritty life of African artisans, I was being cured forever of my elitist art mentality. I was being plunged into and pulled through a world of true struggle, of embodied making, a world of splinters and sandpaper, a world of poverty, of strange and surprising joy, a world of life-or-death stakes. Six years into our experience, when I moved my family to the Tabaka hills where the Kisii stone was hiding, all my illusions of art had finally been chipped away. Like a long-protracted baptism, I was at the bottom of the waters and ready for a new beginning. It was a virginal state already prefigured in the stone itself.

***

Steatite carving had a long, robust tradition in the Byzantine Empire. In the Anatolian peninsula, one could find spotless green samples of soapstone for carving. The Byzantines called this stone amianthus lithos, unspotted or immaculate stone. For some of the medieval poets, it became a symbol of materiality itself and of the Blessed Virgin, whose immaculate body became the place and matter of the incarnation.

Blessings upon you, sculptor’s hand,

on the stone from the mountain uncut by hands

him you delineate on unspotted stone

who came forth from the unspotted Virgin.

The paradoxical capacity of matter to contain the God-Man became, for these poets, an image of our encounter with and participation in art. The highest truth and purpose of art, like the tabernacle of the Old Testament, is to become a place of theophany.

I honor you, o stone, although you are small to look at,

nevertheless you contain within you the uncontainable.

But you are truly unspotted,

because you represent the unspotted mother.

There had not been convincing steatite carving in Orthodoxy since the fall of Constantinople. It was an art almost forgotten by anyone but scholars.

***

In Tabaka, looking at raw Kisii stone tiles with excitement, I neither knew nor cared about this absence. I simply wanted to find one that was the right colour and thickness and shape for what I wanted to do.

I befriended several wonderful carvers, including one in particular named Joseph Rachami, whom I asked to teach me. Joseph was known to be one of the master carvers in Tabaka, and he also happened to be a devout Catholic. He had made several statues of the Holy Virgin for churches and institutions around the Kisii area. He took me around the hand-hewn open mines, taught me the different consistencies of the varied stones. I saw the process of mining, of preparing and cutting the stones into boards, all done by hand with two-person bucksaws.

The actual carving lessons mostly meant trying various techniques and then watching Joseph make the carving nicer, cleaner, finished. He used a mallet and a chisel, but also a carving knife—the main tool of Kisii stone carvers, improvised based on whatever material they could find. Joseph made a knife for me as well: grinded from a recycled steel file, sharpened and polished, with a handle comprising two pieces of wood held together by the inner tube of a bicycle tire. He would sometimes come and sit in the grass in front of the house where I was staying, at the end of the day as the sky was becoming pink and yellow, holding the stone boards between his feet and hacking away with a mallet and chisel—a practice that I never dared imitate for love of my ankles.

When I look at the icons I made in Kenya, I am almost embarrassed. Despite the goodwill and help from my friend Joseph, there are many mistakes that now seem glaring to me. But I can also see how much I progressed. I have kept many of those images, and today I can consider those last few pieces I made in Kenya with warm nostalgia.

***

Those moments in Tabaka brought my family’s time in Africa to an end. We returned to Canada to start a new life. I brought with me a small shipment of Kisii stone and a dream that I dared not utter too loudly. Was it possible to reawaken soapstone icon carving after more than five hundred years? Was it possible to live as an Orthodox icon carver in North America, returning from a seven-year stint in Africa with two young children and a pregnant wife?

I dared not think any of that out loud, but a secret prayer turned in me, a desire to participate fully in the life of the church as an artist, finally—integrating my faith with my art-making, making objects that were true not only in message and form but also in purpose.

Seven years as volunteers in Africa taught us to be poor, and so we lived a simple life upon our return. Various job opportunities emerged and then fell through. Despite the madness, my wife and I were calm. We prayed, and miracles happened. In the few years after we returned from Africa we were gifted three cars—one by a woman my wife had met only a week before. We received cheques in the mail from people we did not know. We found bags of children’s clothing on our porch. Once, when we needed several thousands of dollars and had no idea where to get the money, a good friend called us. Without knowing our problem, she told us she had been convinced in prayer to send us an amount that almost exactly matched what we needed.

Through the almost two years we held our breaths, and I decided to do what my hand found to do: I carved. I set up a makeshift workspace in the basement. I made a little website. I showed my bishop what I was doing, and he asked me to make a pendant for him, my first commission. I carved that first icon, then a second, then a third.

That was ten years ago now, and I have not run out of commissions since.

Now after my morning prayers, I walk behind my house to a small workshop we built there. If I am early enough, the streaming sunrise pierces through the leaves of the wooded area there. The sun reflects directly on a small canal that reaches back into the trees. On my workbench next to the window is a steel mallet and a series of handmade carving tools: files, punch tools, wood chisels, all ground to various needed shapes and reminiscent of the improvised knife I was given in Tabaka. That particular knife is also still there among the others. Clamped down on the carving table is usually the half-finished icon of Christ or of a saint. Sometimes in wood—I use that too. But most often the icon is made of Kisii stone. As I carve something, I thank God for all the opportunities I have been given to participate in the beauty of the Christian tradition, a beauty made possible and full in the incarnation of the divine Logos, light of the world who shines in the darkness.