I

Institutions are floundering. Churches are suffering through a long and disjointed remaking. Families are exiting public schools at record rates. Universities, once critiqued from within by progressives hostile to signs of neo-liberal corporatization, now face sharp attack from without. Even amid an epidemic of loneliness, when no one really enjoys “bowling alone,” institutions seem ever more distrusted across the spectrum: the Right rails against waste, fraud, and abuse, while the Left fears complicity with injustice. It is clear to everyone that we face challenges requiring collective solutions, yet we struggle to build and tend the durable structures capable of meeting them.

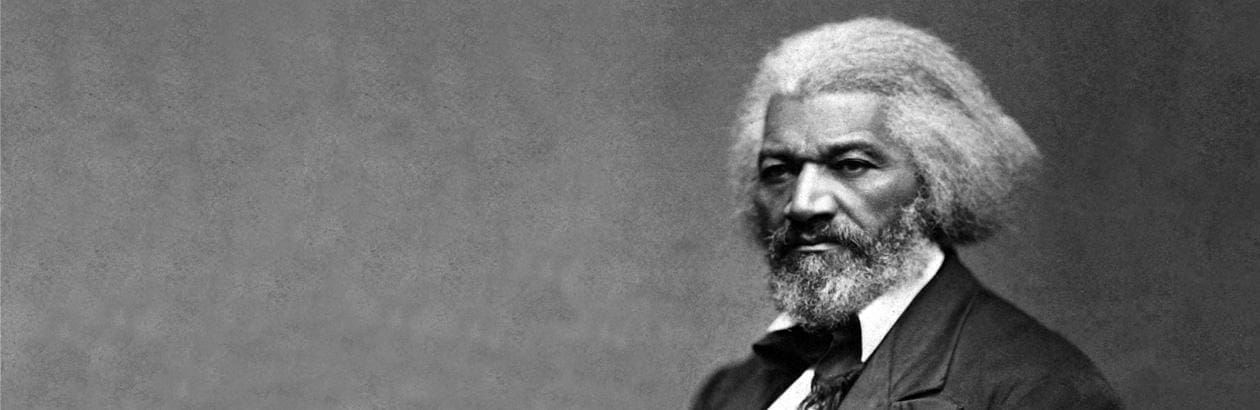

I have become fascinated with the abolitionist James Pennington, especially for the ways he navigated institutions in pursuit of an end to slavery. One of those institutions was my own university, Yale, which begrudgingly gave Pennington a theological education from 1834 to 1837. Though little remembered today, in his time Pennington’s name was spoken alongside that of Frederick Douglass, whose wedding Pennington officiated. His memoir, The Fugitive Blacksmith, sold like hotcakes, and Pennington travelled widely through the British Isles and the Continent, speaking to packed churches. The University of Heidelberg awarded him an honorary doctorate. And yet in 1879 he died in obscurity, his reputation undone by the fraught task of mediating between church institutions and the abolitionist movement. In some respects he was stupendously successful; in others he hardly made a dent. Pennington’s story may help us in our own faltering efforts to find a way forward in our lives with institutions.

Pennington was born into that “peculiar institution” of slavery in Maryland around 1809. His loving parents did their best to hold their family of twelve together even when James and his mother were sent to a plantation on the other side of the state. When he escaped at nineteen, making his way first to Pennsylvania and then to New York, it was with a heavy heart for family members left behind and a burning desire not simply for his own freedom but for the freedom of all still in bondage. He had the good fortune to be taken in by Quakers, who taught him to read and write and introduced him to Christianity. That first taste of education fuelled a passion that carried him to New York City, where slavery had been abolished only one year prior. While working for a carriage maker, Pennington attended Sabbath and evening schools and hired private tutors, advancing with astonishing speed. Logic, rhetoric, Greek, astronomy: in just a few years Pennington leapt from illiteracy to the upper reaches of higher learning. In the same period he embraced the Christian faith unknown to him in childhood. In The Fugitive Blacksmith he wrote that slavery “seemed now as I looked at it, to be more hideous than ever. I saw it now as an evil under the moral government of God—as a sin not only against man, but also against God. The great and engrossing thought with me was, how shall I now employ my time and my talents so as to tell most effectually upon this system of wrong!”

There was, however, no obvious path forward, no vocation neatly labelled “abolitionist,” no anti-slavery societies to join:

Eventually, he resolved to enter the ministry, at the time the only learned profession open to blacks. The path was not easy. The Fugitive Blacksmith breaks off here, forcing us to reconstruct his story from other sources. The Quakers who had shown him such kindness left a lasting impression, but their rejection of ordained clergy and insistence on every person’s direct access to the divine light made them an imperfect fit for the exercise of Pennington’s leadership gifts. In Manhattan he had come under the tutelage of a Presbyterian minister, Samuel Hanson Cox, so Cox’s denomination was a natural choice. He prepared for the ministry at Yale Divinity School.

Founded in 1701 to train Congregationalist ministers, Yale had added a Divinity School in 1822. By the 1830s it was rooted in the New Divinity movement sparked by Jonathan Edwards and closely tied to reform-and-revival-minded currents in Congregational and Presbyterian churches. Pennington arrived at Yale in 1834 and studied for three years. He was prohibited by Connecticut law from registering formally or obtaining a degree. He was even forced to listen to lectures from outside in the hallway. Yet he persisted, and his thought bears the imprint of those years. As the Heidelberg-based religious historian Jan Stievermann has shown, Pennington soaked up the ideas of Samuel Hopkins (1721–1803), who had developed an anti-slavery theology based on the Edwardsean doctrine of benevolence. (Edwards himself never addressed the issue of slavery and had owned at least four slaves.) Pennington also creatively adapted the ideas of one of his Yale teachers, leading theologian Nathaniel William Taylor (1786–1858). While Taylor himself was no friend of the abolitionist cause, he had a great deal to say about human freedom and the “moral government” of God. Pennington found this notion admirably suited to articulating his core convictions concerning the cooperation of human action with divine providence in bringing about an end to slavery.

Despite not having a degree to show for his three years of theological study, Pennington succeeded in obtaining ordination in the Presbyterian church. He spent his subsequent career ministering to Presbyterian and Congregational congregations, mostly in Connecticut and New York. The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, a separate Black Methodist denomination, had been founded in 1816 by several African American Methodist congregations resisting discrimination within the larger Methodist Episcopal Church. The Presbyterian and Congregational churches, by contrast, were overwhelmingly white; black worshippers were typically relegated to balconies and only rarely broke off to form their own congregations. All the more remarkable, then, is that Pennington, ministering to black congregations within these denominations, succeeded in rising to the highest levels of leadership. William Simmons, in his 1887 Men of Mark, noted that Pennington was “twice elected president of the Hartford Central Association of Congregational ministers, composed exclusively of white men.” He was later elected moderator of the Presbytery of New York, another predominantly white body.

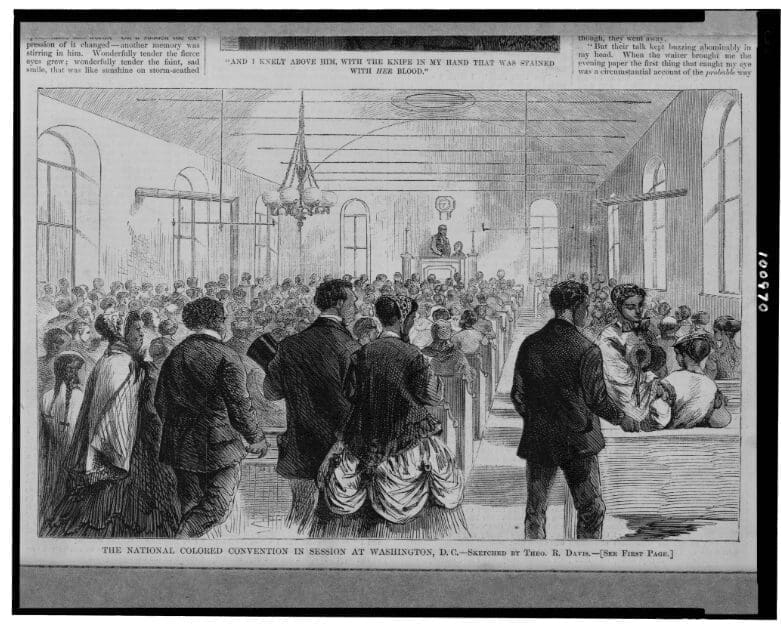

Even as he worked his way into positions of increasing authority within church institutions, Pennington was also helping launch the anti-slavery movement he had earlier sought in vain. In 1830 he attended the very first National Negro Convention in Philadelphia, eventually becoming its presiding officer. The National Negro Convention movement, which gathered momentum and continued until the end of the Civil War, gathered black leaders together in search of lasting ways of improving the condition of blacks in the United States. Meanwhile, in 1833 the American Anti-Slavery Society was founded—an answer to Pennington’s prayers. He soon came to know white abolitionist leaders like William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan, who visited the National Negro Convention in search of black allies. In 1843 Pennington attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, sent by Connecticut as the state’s delegate-at-large.

Pennington’s activities within church institutions were complementary to his activities within the Negro Convention and anti-slavery movements, at least up to a point. While in London for the World Anti-Slavery Convention, Pennington was invited to speak at many area pulpits, advancing his abolitionist theology. Returning home, he impressed on his white colleagues the stark contrast between the warm reception he had received abroad and his treatment at home. Many were spurred into inviting Pennington to preach from their own pulpits. In Scotland on a lecture circuit when the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850, Pennington, as a runaway, remained abroad for several more years to avoid capture. Shiloh Presbyterian Church, to which he had been called in 1850, patiently awaited his return, which took place once friends succeeded in raising funds sufficient to purchase his freedom. Back in New York, Pennington was arrested for riding a whites-only streetcar, launching a movement of civil disobedience that culminated in a successful appeal to the State Supreme Court, which in 1855 ruled racial segregation to be illegal. In this he anticipated tactics of the civil rights movement a century later, drawing—like Martin Luther King Jr. would later do—on the networks opened up by his leadership within church institutions. He was also thinking globally while acting locally: that same year he appealed to the Colored National Convention to launch a “grand fusion Western Continent Anti-slavery Extension Convention” that would bring together “gentlemen of talent from the British, French, Spanish, and Danish Dominions, and also from Mexico and Central America.” His imagination reached beyond the abolition of US slavery to encompass a broader decolonizing vision.

But trouble was brewing. By year’s end Pennington had lost his pulpit at Shiloh Presbyterian Church, undone by rumours of secret alcoholism. In truth he was a casualty of tensions within the abolitionist movement. Arthur and Lewis Tappan, splitting off from the Garrisonian American Anti-Slavery Society, had formed their own rival American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, and a major fault line ran through the churches: the Garrisonians decried them as lukewarm and gradualist, while the Tappans insisted on working within ecclesial structures. Pennington got caught in the crosshairs. In 1853 he attended the Presbyterian General Assembly, which allowed slaveholding Southern pastors to participate. Though Pennington had spoken out against communion with slaveholders and endorsed their excommunication in 1853, his attendance was seized on by the Garrisonians, who moved to destroy his reputation.

In an open letter published in Frederick Douglass’s paper in 1855, Pennington sought to defend himself: “You are aware, perhaps, that statements have been going the rounds for some time past, tending—I will not say designed—to convict me of pro-slavery sentiment and action.” Having sought to avoid controversy, Pennington had long remained silent, but he was persuaded that “there is a point . . . beyond which even forbearance ceases to be a virtue.” That men “belonging to a race which has done so much to oppose, wrong, and outrage my race, should take so special pains to convict me of treachery to my own race, is beyond endurance.” Ardently defending his stance in favour of immediate emancipation and active resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act, Pennington wrote, “When I escaped from slavery in our state of Maryland, there was no vigilance committee in existence—there was no one of the present anti-slavery societies in existence—that no one of the present anti-slavery leaders had appeared upon the platform.” He owed his convictions to no one and felt “indignant at the thought of asking any man or party of men to endorse my abolitionism.” Attacked by erstwhile allies, Pennington’s independence of mind was on full display. Despite his fierce rhetoric, however, Pennington was no match for his powerful white critics. His reputation in shreds, he fell into obscurity. He went on to pastor several other churches but was never again to command large audiences or lead movements. After the Civil War, feeling called to participate in reconstruction efforts, he moved down to Florida to organize an African American congregation there, but he died soon after in 1870, felled by a tropical virus.

It is clear to everyone that we face challenges requiring collective solutions, yet we struggle to build and tend the durable structures capable of meeting them.

What can we learn from Pennington’s efforts to work within institutions and movements to resist oppression and advance justice? Quite a lot, I think. Let me try to articulate four lessons that might guide our own path forward.

First, Pennington did not wait around for a perfect institution, one worthy of his devotion. His driving question was “What can I do for that vast body of suffering brotherhood I have left behind?” In a letter to his family in 1844, he wrote of the “support and comfort” he had found “from that blessed Saviour, who came to preach good tidings unto the meek, to bind up the broken hearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to them that are bound.” But he harboured no illusions about the compromised character of either the Congregational or the Presbyterian denominations. Disrespect and disregard for black congregants and ministers were the order of the day. Pennington knew recognition would be hard-won. Yet he poured his energies into working in and through these flawed institutions to preach a gospel that he found clearly to be as “anti-slavery as it is anti-sin.” He refused to yield that gospel either to the forces defending slavery or to the forces defending gradualism and delay. Today, when purity-seeking and critique so often stymie our capacity for commitment, Pennington embodies a generative alternative.

Second, Pennington refused to choose between working within established social institutions and running with issue-based social movements. He embraced both. His faith found natural expression and support in communal worship and Bible study. Ordination offered a locus for meaningful service to the black community. It also opened doors for significant leadership that crossed racial barriers and that tapped into well-established national and international networks. At the same time, Pennington threw himself into the National Negro Convention movement and the nascent anti-slavery movement. He experimented with new social change tactics from boycotts to acts of civil disobedience. He worked outside established institutions, building new coalitions and working across religious denominations. He did not expect either the Presbyterian or the Congregational Church to be the answer to all prayers, the conduit of all forms of social transformation. Here, too, we find a valuable take-away: invest in institutions and movements. Reject the false either-or; both offer powerful resources and methodologies for advancing the common good.

Third, Pennington played the long game. Encouraged by Britain’s 1834 Slavery Abolition Act, which freed 750,000 enslaved people in the West Indies, he saw in it evidence of God’s “moral government.” He was convinced that the natural law of human equality was “engraven on the more durable parchment of the human mind,” whatever the US Constitution said, and “destined to become the law of the world.” He argued passionately for immediate abolition and, while believing in the possibility of a peaceful end to slavery, defended armed resistance to unjust human laws when war came: “If this be rebellion against the powers of earth, we have only to say that it is loyalty to God.” Yet he never claimed to know the time scale on which divine providence would play out in human history. Assured that history was in the hands of God, he knew his job was simply to persevere.

Last, Pennington drew on deep reservoirs of personal resilience and self-reliance. He worked within institutions but did not derive his worth from them. He knew himself to be loved, knew himself to be, like all persons, a site of infinite worth. He encountered this initially through the love of his parents and siblings, later discovering the love of God as the encompassing ground and source of that unconditional affirmation. He sought respect and recognition from others, pursued power and influence within institutions and movements, because he knew these were ways to act on behalf of “that vast body of suffering brotherhood.” But his own sense of self-worth did not flow from the recognition that he received within these social institutions, and thus could not be taken away by those institutions. Here lies a word of wisdom: invest unstintingly in social institutions, but know that your value transcends them. This can enable you to ride the stormy waves of institutional change with inner calm.

James Pennington is not a household name like Frederick Douglass or Sojourner Truth. Though his reputation was so effectively shredded by the cancel culture of his day, we should be slow to judge him a failure. Today he is being rediscovered. When I arrived on the Yale faculty fifteen years ago, no one there knew of Pennington or of his remarkable story. His portrait now hangs in the Divinity School Common Room, and his name graces a favourite classroom. In 2023 Yale University recognized his work with a posthumous degree. Heidelberg University, proud of the honorary doctorate it conferred in his lifetime, now awards an annual Pennington Prize to scholars who extend his legacy. We are rediscovering Pennington because he made a difference during his lifetime. He changed hearts, minds, laws, and social practices through his speeches, sermons, writings, organizing, acts of civil disobedience, tireless movement work—his life in and beyond institutions. Perhaps we can too.