D

Dissident—it’s the word most associated with Czech philosopher Jan Patočka, who, for most of his life, was banned from teaching and publishing in his native country. Yet despite finding himself at odds with the government, and despite his animating role within a community of dissidents, Patočka chose a different word to describe his position: heretic. Both attitudes, dissidence and heresy, bend from the signposted path. “Dissident” is a political word. “Heretic” is a religious one. Why did Patočka, not a religious man or philosopher of religion in any obvious sense, think this the more fitting term, when disident was a word in free circulation, used both by the Czechoslovak secret police to identify troublemakers and by those same troublemakers as a badge of honour? I imagine Patočka disliked being defined in opposition to something, rather than by what fired him from within. And he no doubt felt philosophical affinity with hairesis, “a taking or choosing for oneself.”

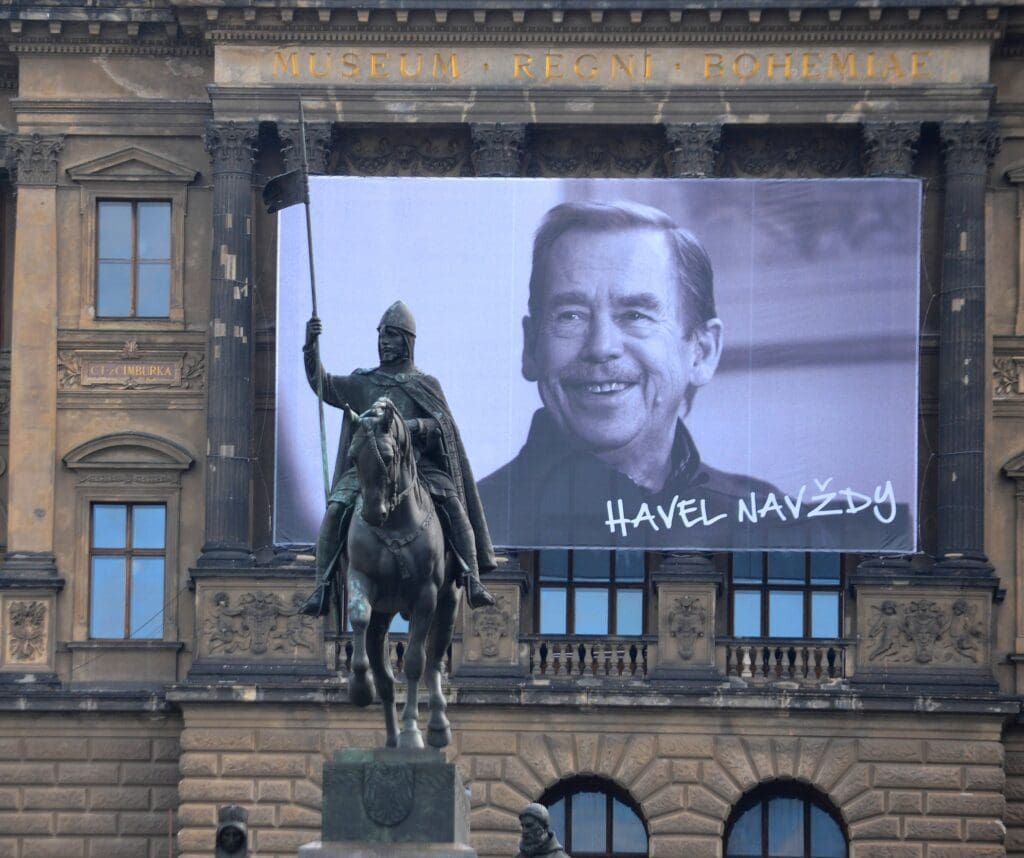

Patočka, with his difficult-to-pronounce name, PAH-totch-ka, is not widely known outside his native context. Living through a period darker than our own—two world wars, Nazi occupation of his country, a repressive Soviet regime—he spoke of the forces of the night that philosophers often ignore and returned often to the fragment of Heraclitus: “All things come to be through strife.” His witness and insight, which meant so much to Václav Havel and other dissidents, still speak to those living through times of crisis. The first English anthology of his works came in 1989, with the fall of the Berlin Wall. The second, which I edited along with one of Patočka’s students, was published in 2022 on the heels of Brexit, Trump’s first term, the global pandemic, and widespread economic upheaval. Patočka might have smiled at this. For him all things are born through strife: solidarity, community, and especially truth.

Patočka is known as the Socrates of Prague, a reference both to his commitment to philosophical questioning and to his death, like that of Socrates, in the service of a truth the state did not recognize. But I’ll resist the temptation to skip to the end. Cultured and scholarly, Patočka was not “political” in any overt sense, despite being labelled a dissident. He had no public life to speak of. He dedicated himself to thinking, writing, and teaching. For years, unable to earn money as a lecturer, he worked in the archive of seventeenth-century Christian philosopher Comenius, doing the meticulous, quiet work of an archivist. He wrote long studies of Plato, Aristotle, and Edmund Husserl. He exchanged ideas with friends, like the Protestant theologian Josef Bohumil Souček, with whom he discussed matters of faith, myth, and the meaning of Christianity. He taught seminars on Plato from his living room when he was banned from university teaching. It might come as a surprise to learn that these were quite popular. Toward the end, they were even attended by the secret police, known in Czechoslovakia as the StB, who were keeping an eye out for the corruption of public morals. It was a running joke among Patočka’s students that the informants could have become excellent philosophers, had they bothered listening to all those lectures.

It has never been easy to resist lies, when they are so pervasive and ready off the shelf for immediate use.

The themes that dominated the seminars were truth, the polis, meaning, care for the soul. One of the most difficult demands of Patočka’s philosophy, adopted by Havel as the guiding principle for the type of life he and other dissidents were fighting for, was life in truth. It is hardly a radical idea that life should serve truth, that the absence of truth leaves us less than fully alive. Yet it has never been easy to resist lies, when they are so pervasive and ready off the shelf for immediate use. The “hypnotic charm” of ideology, as Havel has it in The Power of the Powerless, is that it removes the responsibility of finding my way in the absence of existential certainty:

It seems that those who orient themselves by conscience are bound to be without a fixed address, since living in truth does not mean the possession of truth, whether confessional or creedal. It is, rather, a matter of heresy, of choosing the path for oneself. This emphasis on decisive responsibility without security also warns us that truth does not mean slavishly following the factual—idolum facti: in my case, obsessively reading and listening to the news to track the latest affronts to human dignity. As Hannah Arendt writes in her essay “Truth and Politics,” “The chances of factual truth surviving the onslaught of power are very slim indeed; it is always in danger of being manoeuvred out of the world not only for a time but, potentially, forever.” It is important to fight the manipulation of reality that untruthful societies of all kinds rely on. But factual truth can become its own idol, as if knowledge were an end in itself, or as if simply knowing a fact necessitated some conclusion. Where one stands in relation to facts depends on a higher-order question of what life is for, which neither ideology nor factual truth can answer.

Patočka offers two basic ways in which we find purpose: one mythical, relying on a predetermined meaning and so oriented toward the past, and one problematic and open to the future. While “problematic” is a word we use to talk about YouTube comments and opinions on X, for Patočka it was the marker of a life lived in truth. “Problematicity” points to the potential of human freedom to break open established structures of understanding and to work toward a truth that is glimpsed only as possibility, but longed for. Truth is an attitude of committed seeking, of risking without knowing, as in Socrates’s willingness to die for a good he could not see around him and that was not recognized by the society in which he lived.

Patočka was a devoted reader of Plato, with a love of ancient Greek learned from his schoolmaster father. He recounts how, in Plato’s dialogue Gorgias, Callicles admonishes Socrates to “let go of impractical philosophy and its paradoxical doctrines—such as that legality and truthfulness are under any circumstances better than their opposites, or that a harmonious life is happier than a wicked one” because “if he will occupy himself with or even conduct himself by his unrealistic philosophical thoughts, he will be disgraced in the city and die.”

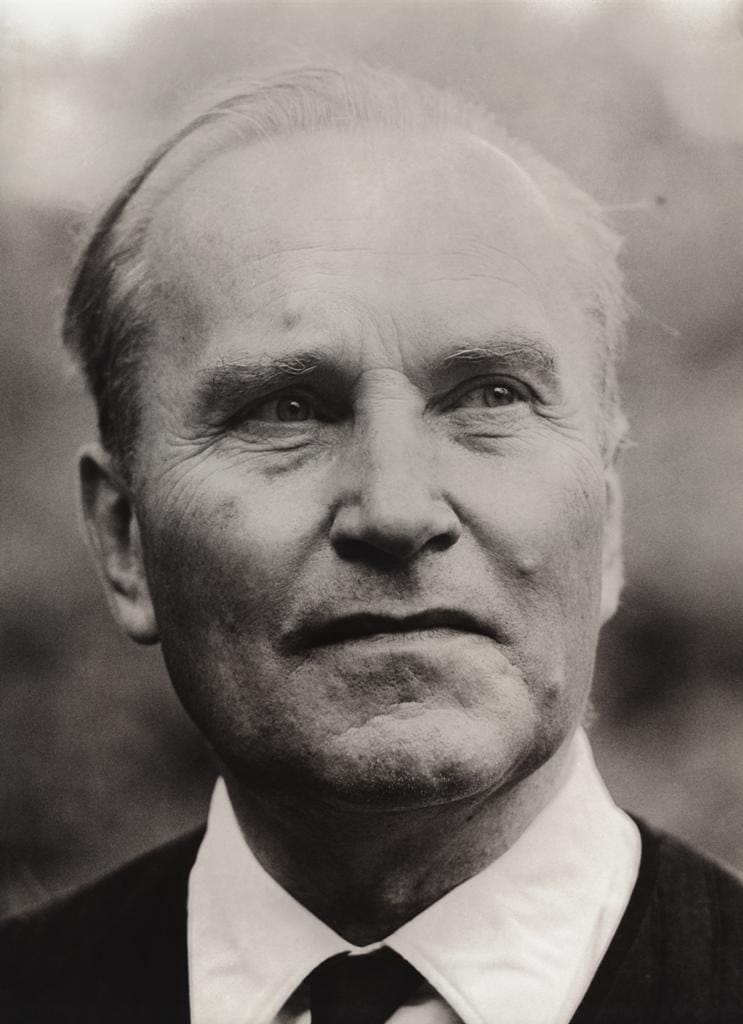

Jan Patočka, 1971. Photo: Jindřich Přibík

What does truth matter, Callicles asks—what’s the point? It won’t win you influence; even those close to you will be frustrated that you can’t simply see things like everyone else, speak like others do. Disgraced, killed—for what? Callicles wasn’t wrong. More often than not, the “perfectly just and truthful man” is not recognized as such. At best he is impractical and naive, at worst a “loser,” a “sucker.” Meanwhile “the perfectly unjust hypocrite and fraudster,” Patočka tells us, commenting on Plato’s Republic, appears as the embodiment of justice and truth, dealing out retribution, telling it like it is. “The former ends up on the cross, while the latter becomes the king and ruler of this world.” Or at least president of the United States. Why align oneself with the cross? Why take the difficult road? “Dost thou still retain thine integrity?” Job’s despairing wife asks him. “Curse God and die.” Yet we’re told Job kept asking questions. And Socrates, when the time came, preferred to die a truthful man.

When members of the experimental Prague rock band the Plastic People of the Universe were thrown in jail in 1969, Patočka wrote an essay on their behalf. Patočka, in his cardigan and tie, looking like someone’s grandfather, was not “down with the kids,” for all that the StB followed his underground philosophy seminars. Yet his essay argued for the importance of creativity, art, and freedom of expression, even when noisy and not to his taste, as means of feeding the soul. The Plastic People of the Universe are, in his telling, an example of refusing to live a lie, by refusing the forms of representation—heavily censored as they were—that were on offer. Patočka’s essay offers a veiled but clear indictment of his own society, and a hope that, however settled and closed matters seem, new ways of seeing and of living are possible.

The act of rejection, of not participating (“I prefer not to”), is impractical and naive, just as Callicles claims—but this refusal of the practical, of what everyone else knows and accepts, creates friction, unsettles. The naïveté that American scholar of Czech history Jonathan Bolton ascribes to the Plastic People of the Universe and to the Czech dissident movement more broadly is an iteration of something older, a Socratic irony that is perfectly earnest in its claims not to know what the rest of the world thinks it knows. To certainty, to the way things are, it restores a large, ungainly question mark. Is that right? It’s a question my nine-year-old has started appending lately to all my statements.

“It’s time to go to bed.”

“Is that right?”

“You know you’ve got to take a shower.”

“Is that right?”

Yes, it’s just as annoying as it sounds. Yet how beautiful, Patočka says, is that power to overturn settled matters by simply missing the point of them. Patočka’s mention of grace in this context is noteworthy—after childhood has ended, it is a gift to discover again the earnestness and openness that says “Is that right?”—and politically significant. Asking questions, refusing to see the point, calmly going about living in ways that are out of step with the times: these activities lay the foundation for a genuine politics that is based on neither low-rent ideology nor cynical pragmatism. They offer an alternative perspective by which the lies of the present can be exposed. For Patočka, “politics in a deeper sense cannot do without their interventions; it would grow coarse and lose itself in demagoguery and utilitarianism.” Such an outlook gives us a framework for thinking about Patočka’s philosophical activity as having political value, even though he mostly avoids direct engagement in politics.

“Political,” in Patočka’s thought, means caring for the polis, tending to the conditions that make life in common possible. These conditions are not political in the ordinary sense of the word but have to do with caring for that part of ourselves (and our neighbours) that cries out for truth, for meaning—in short, care for the soul. This is why, for Patočka, the life in truth is a political life: it is forged in times of uncertainty, when assumptions about the nature of what is and what is possible come undone, so that the question of what we want our lives to be like is raised anew, or perhaps for the first time. One begins wandering. A community is formed within this activity of unsettlement: the “solidarity of the shaken.” In this account, the foundation of political life and solidarity with others is not identity, of whatever kind, not the natural affinity we feel toward people like us, not the securing of rights, nor rational self-interest, but a shared experience of crying out for meaning and refusing easy answers.

For Patočka, the life in truth is a political life.

The ideal social and political form would be one in which the person who has cultivated truth and justice, who has looked after the matters of the soul in themselves and in others, could live happily and unharmed. But we do not live in this world, and neither did Patočka. As he saw it, the solidarity of the shaken can look after matters of the soul only by saying no, like the spirit that guided Socrates. Such a community works by issuing “warnings and prohibitions. It can and must create a spiritual authority, become a spiritual power that could drive the warring world to some restraint, rendering some acts and measures impossible.”

Yet as much as the relationship to power in this picture is limited to saying no, there is a further, existential element that is more positive: if some acts become unthinkable and impossible, it is because, at the same time, other ways of comporting ourselves become possible. This is where the spiritual authority comes from, that vivid sense of an otherwise. It is just where I don’t see justice that my soul demands I commit myself more firmly to it. Truth works for more truth. “The only real help and care for the other comes when I step forward and do what I have to do, whether in hiding or out in the open, whether anyone knows about it or not, and perchance to let my awakened conscience awaken the conscience of others.”

Our responsibility to live our lives, to lead them, in Patočka’s terminology, is “felt increasingly as the external pressure grows stronger.” To lead a life—isn’t that what we’re doing all the time? We exist, by default, in some factual, unasked-for way. But however much of our energy this requires, and these days it’s a lot, some other energy in us surges up, anxious and dissatisfied with this maintenance of life. Patočka calls this movement “soul”: “When the soul, that is, our unobjectified component, our connection to the infinite . . . awakens and demands its rights, then all of a sudden the way we move among things, our reactions to life become unsettled, unpredictable; things happen that never happened before.”

To lead a life, to care for the soul, is for Patočka not simply to exist, however nobly or reluctantly or awkwardly. To act, in the broadest sense, is to value, this and not that. But to lead a life means to take responsibility for this capacity to affirm value, showing through my actions what really matters. Absent that, my actions affirm the value of however things happen to be, the way things ordinarily go. There is no neat line to be drawn between private and public life, since attending to my soul, or not, tells.

In 1976 Patočka made a decision that seems, from our vantage, the natural issue of his philosophical concerns, even though, read in another light, it is uncharacteristic of the man who had for so long dedicated himself to scholarship. He became a spokesperson for what would be known as Charta 77, a modest document defending the human rights of the Czechoslovak people, addressed directly to the government. In choosing this role, Patočka put himself in the public eye for the first time, signing his name to an accompanying essay and meeting, famously, with the Dutch foreign minister to draw attention to the situation in his country. He made himself the target of harassment and surveillance by the StB, whose informants included Patočka’s own doctor. Knowing of his ill health, the StB called Patočka in for questioning repeatedly, and in March 1977 he died of a stroke, a week after a particularly intense eleven-hour interrogation. They raided his home (luckily, not until after two of his students had gathered up all his manuscripts for safekeeping). The state interrupted his funeral by flying helicopters overhead. A year later Havel dedicated The Power of the Powerless to Patočka’s memory. Charta 77 became a widespread civic movement, eventually helping to topple the Soviet government and elect Havel president. Patočka became the Socrates of Prague.

Patočka’s reasons for getting involved with the charter are not the reasons of a political dissident. They are the reasons of someone addressing a much wider set of concerns than how his country is run and by whom. They are the questions of a heretical thinker looking at the whole crisis in European spirituality, the dominance of technoscience (his term) and instrumental rationality, and asking higher-order questions: Does such a framework serve humanity? What are we doing with our common life—can we find solidarity in our unsettlement and seeking, or only in our certainty? These are the same questions we must ask for ourselves.