T

To seem the stranger lies my lot, my life

Among strangers.

—Gerard Manley Hopkins

The first human experience is our exile from the garden. The loss of this home signals the beginning of a discrete self, the blossoming of anxiety, and seems to mark us for life with a longing. A feeling that every home is only an approximation. Christianity makes this explicit with the notion of earthly life as a temporary sojourn on the way to our true spiritual home. Many hymns and spirituals give voice to this feeling of not being at home in the world:

This world is not my home

I’m just a passin’ through . . .

If heaven’s not my home

Then, Lord, what will I do?

The angels beckon me

From heaven’s golden shore

And I can’t feel at home

In this world anymore.

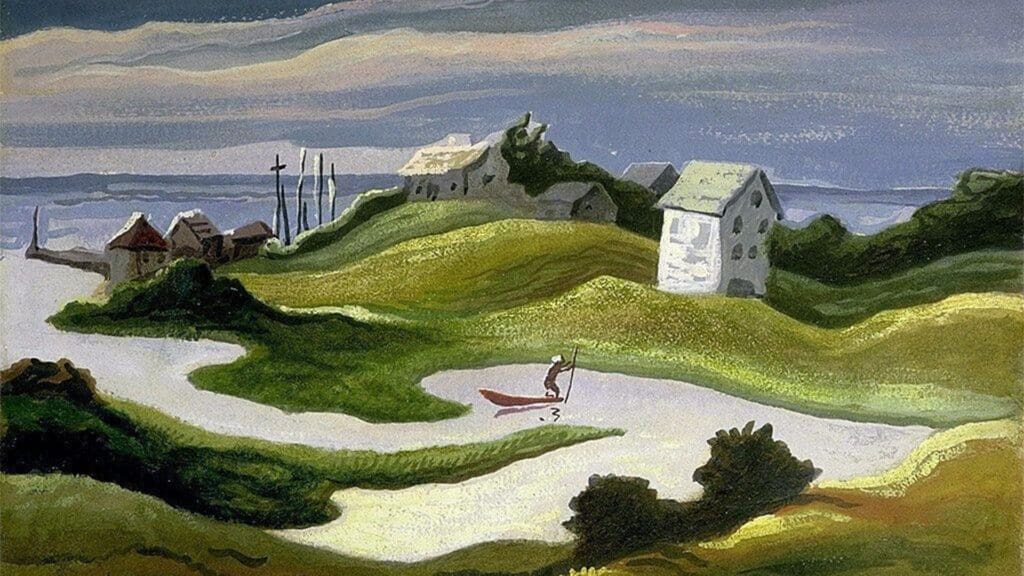

It is a curious feature of being human that we can experience the uncanny in the midst of home. Yet the same restless impulse that drives us away from home also moves us toward something: a distant shore or self that we recognize as our own. It tugs at the edges of memory and imagination. The German Romantic poet Novalis describes our travels as immer nach Hause—always homeward, never reaching home. I am drawn to this understanding of existence as a pilgrimage in which I am always on the way. But then, I would be.

I grew up on an evangelical commune in Indiana. Here I was housed and became unhoused. From here I journeyed. The exoticism of such a history, in the context of my inherited home of London, never fails to have an effect: I become interesting, a bit weird. On occasion I am really seen—by a fellow traveller. But lately I have become testy around my origin story, which has started to feel like well-rehearsed material. This is perhaps the inevitable result of dragging into the light something that was once intensely private. It becomes part of a public self, the list of attributes, anecdotes. “Here is Stephen, who works in publishing, and here is Erin, who grew up on an evangelical commune.” Even the words sound wrong. “Commune.” “Evangelical.” I learned them only after the fact, and they refuse, mulishly, to stick to the place that was home. It is a though acquiring a more precise vocabulary has caused the primary experience to flow outward in all directions, pooling in some other, nameless place. To us, at that time, it was just “the campus.”

The German Romantic poet Novalis describes our travels as immer nach Hause—always homeward, never reaching home. I am drawn to this understanding of existence as a pilgrimage in which I am always on the way.

The campus, a nod to the purported scholarly activities of The Way International™, was a relic of late nineteenth-century institutional architecture, sitting high on a hill in red-brick handsomeness, partially hidden by evergreens. It looked like a large School for Young Ladies and to the passing driver presented a slightly spooky appearance. Perhaps an asylum? The sign out front read: The Way College of Biblical Research, Rome City, Indiana. Families from all over the country joined the two-year Way Corps, as it was called, to draw closer to God and to train for a life of ministry. There were several hundred of us there in the high times, filling the dormitory-style rooms and townhouses. Life for the corps was ascetic, highly structured: four hours of Bible study, four hours of work, and an evening service, with meals taken communally in between. The children were seldom enthusiastic about moving to a Bible college in rural Indiana, though there were many of us, and we had great fun, and we made up a sizable population of the local school. Unlike them, I had no basis for comparison or resentment: I had simply always been there.

My parents joined the Way ministry in the early seventies and moved to the commune in 1983, when I was two. My mom first ran housekeeping, where I learned how to make “courtesy folds” in rolls of toilet paper and vacuum a rug without damaging the fringe, and then the industrial kitchen, where I was always sneaking into the fridge to eat pickles from a five-gallon bucket. My dad was head of the grounds crew and the auto repair shop, permanently red-faced and red-armed from spending what seemed like hours each day on a riding lawnmower, also red. The Way Corps recruits formed the free labour force, rotating through jobs every few months until their two-year stint was up and they were sent out “on the field,” which could be St. Louis, Des Moines, Newark, Boulder, or anywhere in between. Year upon year best friends came and went, sometimes staying in my orbit for a time but ultimately spinning off into a mental void.

I was vaguely aware that the place had continuity over the years as a religious community. For most of its existence it was a health spa, Kneipp Springs, promoting the “water cure” of nineteenth-century Bavarian priest Sebastian Kneipp. Guests were tended to by the Sisters of the Precious Blood, a Catholic order from neighbouring Ohio, who owned and operated the site. The “springs” of the name was a reference to the eggy, metallic spring water we used to dare each other to drink—or, as Kneipp called it, “that pure crystal element which the Creator has so lavishly provided for His creatures.” This was channelled into numerous fountains, ponds, and therapy pools sheltered by yew hedges. The healing waters once cleansed a steady stream of visitors from headaches, blood impurities, catarrh, epilepsy, tinnitus, gas, nervousness, weakness, rheumatism, cramps, gout, asthma, bedwetting, and something called “slime fever.” The pools, long since emptied by the time I lived there, were painted a heavenly light blue, and the thick layers of paint could be peeled away in satisfying chips.

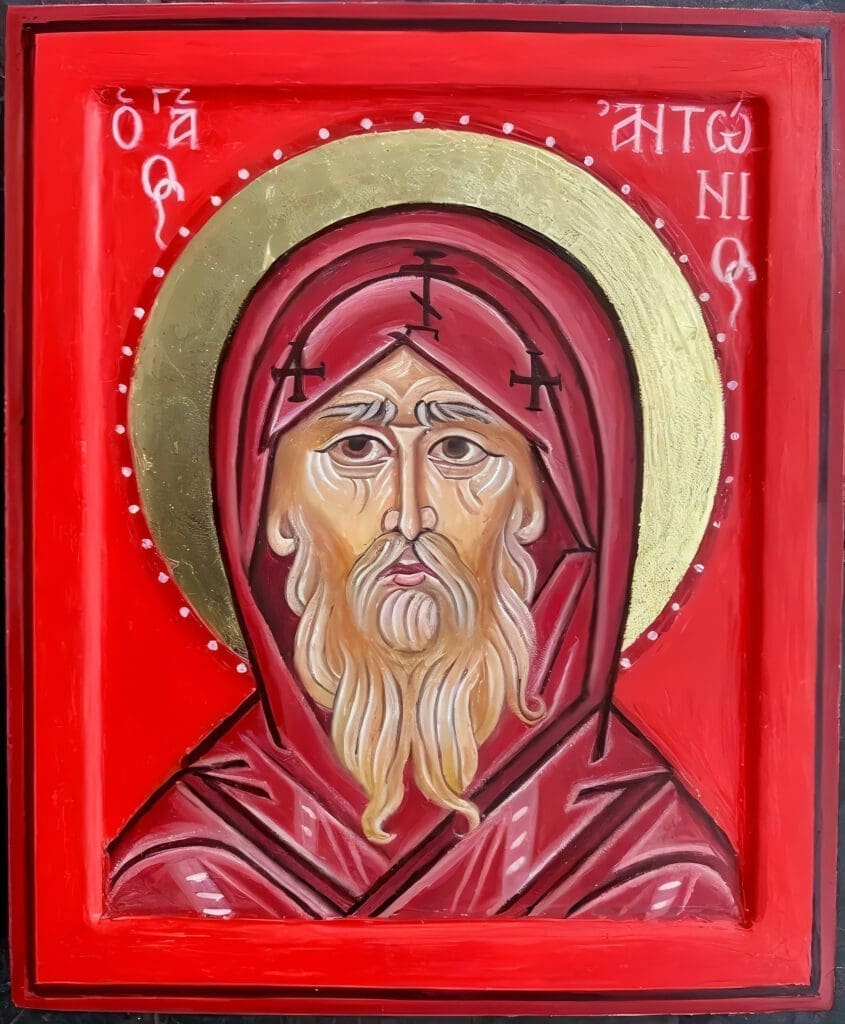

When the Way took over the property and installed central heating and a basketball court, they also removed Our Lady of Lourdes from the rocky grotto, covered the stained-glass windows in the chapel, and otherwise cleansed the property of its Catholic mysticism. Only the shell of the building and the elegant grounds retained the unscrubbable feeling of a Past. There were still weird appendages like a boarded-up blacksmith shop, with its curious blackened tools and anvil and horseshoes still visible through the window; dank tunnels for the sauerkraut barrels; a cemetery just over the hedges from the big blue aluminum swimming pool. In some ways it was a child’s paradise, with endless spaces to roam and play. I remember this most, wandering, alone or with friends, through the grounds, the wood, eating waspy apples, exploring the strange outbuildings, and playing Daniel in the Lion’s Den in the empty grotto. The landscape formed my own inner world. I would not discover until many years later that, on the grounds in 1956, Sister Mary Ephrem Neuzil saw a vision of the Virgin Mary in dazzling white, with a crown of gold: Our Lady of America.

While I have a great memory of physical freedom and space, in truth much of our time was occupied by sitting silently through meetings and mealtimes. I counted myself lucky when I could be in the kitchen during service instead, watching bowls of taco salad disappear into the hall. Our bodies and minds were vessels of Christ, and obedience (Listen, remember, and obey), when not given willingly, could usually be produced by a good spanking. Restless children were always being taken out of the dining room to be “reproved.” My mother preferred a wooden cooking spoon with G-O-D and Proverbs 22:6 written on it in cheerful blue Sharpie. In case I forgot.

I was nestled and contained in my faith. It was a house with room enough for every new idea or stray fear to be tucked safely away. The kids at school sometimes asked me if I was in a cult. When this happened, I would go red-faced and say no. I didn’t know what the word meant—and still don’t. I linked it at that time to news coverage about the siege at Waco, their leader a long-haired sex pervert with aviator glasses. Was that what we were? “I was brainwashed by a cult!” “I escaped a cult!” Some ex-Way followers describe their experience like this, pointing to the rigid hierarchy of the leadership and the constant ideological scrutiny, combined with alienation from their friends and family on the outside. All true. But to my ear, “cult” sounds exotic, lurid, sinister. After all, no one sets out to join a cult, or thinks they are in one.

“Brainwashing,” too, sounds oddly categorical, conjuring up the terrifying image from A Clockwork Orange of a man having his eyelids forcibly opened. But brainwashing, if it means anything, is much more about being encouraged to shut one’s eyes, to fail to see what is not convenient or does not conform. Brainwashing is about making clean and blank the space that once held a relationship, after the people you grew up with or your own dad failed the test of ideological purity. People couldn’t be pure, but it was okay because you got so good at forgetting them. Washed by the healing waters.

In what seems almost too perfect a metaphor, the artesian spring water that had cured all those rheumatic pilgrims was not pure enough for my mother. She passed our tap water through an elaborate distiller with copper tubing until it came out sweet. “Distilled water contains no contaminants or minerals.” My young mind followed a similar process. Be not conformed to this world but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind. Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God. “Renew your mind” was a favourite motherly refrain. But being washed smooth so many times has its effect. The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein speaks of philosophy’s tendency to smooth out difficulties with abstraction. At a certain point, the removal of all the stones and fissures makes the ground so smooth that it becomes impossible to walk, since walking requires friction. He advises, “Back to the rough ground!”

I left in my mid-twenties, gradually, through a series of what-ifs that followed the path of every child’s development. What if I drop the spoon again? What if I don’t answer when Mother calls me? What if I stop reading the Bible, stop speaking in tongues, stop praying? The initial departure, the decision to stop going to my Bible fellowship group, was very much like a child taking her bundle and stick and walking out the front door. Except, unlike the child, I knew (or thought I knew) my family wouldn’t follow behind at a safe distance. The Way had a policy against that sort of thing. The most offensive troublemakers, like my dad, who left when I was fifteen, were labelled “mark and avoid,” and contact was all but forbidden. Others who went quietly were politely shunned or kept at that distance reserved for unbelievers. Be ye not unequally yoked together with unbelievers, for what fellowship hath righteousness with unrighteousness, and what communion hath light with darkness?

I was at university at the time. I told no one about my past, and only a few close friends knew that I attended a Way Bible fellowship. It never occurred to me to speak about it with anyone, in part because they were “unbelievers” and wouldn’t understand, in part because I was straddling two worlds and was desperate to keep them estranged. In one, I was watching New Wave cinema, hanging out at the indie record shop, eagerly devouring existentialism, liberation theology, and queer theory—your typical pretentious undergraduate. In the other, I was speaking in tongues, I wasn’t allowed to drink or be alone with boys, and my tiny dorm room held a twenty-gallon water jug and a huge tub of canned goods because I was prepping for the Y2K crisis. In 2000, after we were declared safe from global catastrophe, the long-time leader of the Way, L. Craig Martindale, abruptly stepped down. I found out on the internet that several women had sued him for sexual abuse and the Way had settled out of court. No one talked about it; people simply stopped speaking his name. I was so used to this kind of vanishing act that I quickly smoothed over the crack it caused. For a time.

They were all good people, I told myself; they all meant well. It was easier to think that. But I had started to spin out, dislocate. They no longer felt like home to me anymore. One morning, heart pounding, I called the nicest one of them to say I needed time away. I had been reading Kierkegaard’s Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing while working the hot dog stand at my university library food court. I searched my heart in earnest, between filling small paper cups with ketchup, and tried to attend to that “still small voice” I had heard about ever since I was a child. I was congenitally prone to self-examination, but there was always a certain fear around finding wrongness there, believing the wrong thing. I did not want to “confess a negative,” to let the devil in. And for a long time that fear dulled another voice. Eventually, the no it uttered wouldn’t be ignored. I started to feel like a phony. I was also, it must be said, a snob, violently sick of the kitsch music and “art” produced by the Way, which was always about “prevailing images of victory” and “living the more than abundant life.” My decision to leave was as much aesthetic as spiritual. I longed for incense, darkness, mystery, some tones that would speak to my soul. I’d convinced myself it was just a break, that I was going away from home for a spell and would return. But the earth opened up; an angel barred the way.

My architecture cracked and crumbled with all the contradictions. Before I knew it, I was no longer a believer. At least, not in anything I recognized. I used to cherish reading the novels of the great American expats, Hemingway, Miller, and James; the exile memoirs of Said and Nabokov. Perhaps because of all those hymns I’d sung, I identified with the feeling of being not at home, of being spiritually elsewhere. It didn’t help that I switched to philosophy. The Greek Cynic Diogenes described himself as at home nowhere, “without a country, poor, a wanderer.” He took to living in a barrel. When I was young, my spiritual restlessness manifested itself as a deep absent-mindedness, a tendency to stand at some remove from my immediate situation. Later, it was tied up with escaping from my received identities: Follower of the Way. American. Eventually it worked to loosen and unbind all the identities I’d found for myself: Nietzschean. Liberal. Existentialist. Academic. Mother. Philosopher. “The perpetual process of becoming is the uncertainty of earthly life, in which everything is uncertain.” Kierkegaard again.

Perhaps leaving home all those years ago was not a straying from faith but an opening toward it.

Can one return home? Lately I’ve started ticking “Christian” on all the forms that come my way. This is somewhat presumptuous, I admit, for someone who does not even believe in the resurrection, or pray, or associate much with Christian community—at least of the living. I have spent the last twenty years asking myself if I might, someday, manage the heedless, uncalculating embrace of uncertainty that Kierkegaard describes as faith. Recently, I started to wonder if caring so much about this question for so long, trying to move closer to this attitude through all my missteps, might be a kind of faith in itself. Perhaps I had been thinking about it all wrong. Perhaps leaving home all those years ago was not a straying from faith but an opening toward it. So that being a Christian now is not so much a return as a claim on a home that I know but have not seen. Perhaps I am walking homeward.

For weeks now, a line has been walking circles in my head: “unhouse and house the Lord.” I thought it was a Bible verse and searched the concordance for “unhouse,” to no avail. In fact, the words come from Hopkins. In “The Habit of Perfection,” the poet asks his senses to withdraw to make space and silence for another reality to be felt. “Be shellèd, eyes, with double dark / And find the uncreated light.” He bids his feet and hands to remember:

But you shall walk the golden street

And you unhouse and house the Lord.

On the golden street in the City of God, the poet himself becomes a tabernacle, a house for the divine, uncreated light. “Unhouse and house the Lord.” Is the Lord, too, then, sometimes homeless, on a journey? I have not dwelt in an house since the day that I brought up Israel unto this day; but have gone from tent to tent, and from one tabernacle to another. I have been unable to find God in America, in the church, unable to see a vision. Yet the Psalms promise that “he shall preserve thy soul. The Lord shall preserve thy going out and thy coming in.” I am out walking the rough ground; I don’t believe in the golden street. Yet perhaps God is out walking too, unsheltered, unshod, into the open.