Y

Young writers often hear the advice “Think about your audience.” And publishers often urge their authors to consider the “reach” their books will have. In our time of “content creation,” globalized communication, and social media networks, it can be difficult for an aspiring artist to figure out who exactly their audience is; and it can be tempting to try to create a piece of art with the intent of maximizing its reach. Implicit in this advice is the idea that the artist is offering something to a particular group of souls but that this group of souls should be as large and as diverse as possible.

I do not like to claim that we are living in “unprecedented times,” because a brief glance at history shows us that very little is unprecedented. That said, our globalized culture presents a particular challenge for artists in identifying the scope of their audience and the purposes involved in making their imaginative offerings.

Alongside an imaginative vision, the artist offers a moral vision, a vision that affects our decisions and shapes our conscience. The idea of art as a profoundly moral action is perhaps unintuitive in our day, but it has a rich history. From as far back as Plato, philosophers have seen that artists in general (and poets in particular) have a significant moral impact on society—for good or, as Plato feared, often for evil. Today we do still conceive of art as having a moral role in society, but we do not use those words. Instead we say a piece of art is “necessary,” “urgent,” “vital”—and what we mean is that it is important for others to witness this art and modify their lives in accordance with what they see.

Art is a moral endeavour, whether we acknowledge it or not. The problem is not that art is too morally minded, but that it is not morally minded enough. Great art, by putting us face to face with some truth, calls us to live differently. Art should touch our wills; it should move us to live and act differently. But in a curious inversion, the best art pushes this change down to the lowest possible level; the best art, for example, does not move us to change our Facebook banner but to treat our friend or spouse or children better. The best art, in other words, draws our attention to our own little circle, our own homes, our own communities—our own province, if you will.

The problem is not that art is too morally minded, but that it is not morally minded enough.

When it comes to art, “provincial” is usually an insult meaning “small,” “backward,” or “dull.” I contend, however, that provincialism can be a powerful tool for an artist, especially in a pluralist society like ours in twenty-first-century North America. Provincialism, a true love of our particular time and place, can give art moral force while avoiding the artistic sins of being prescriptive, domineering, or abstract.

The Imaginative Province

In the second half of the twentieth century, Richard Weaver defined provincialism as “your belief in yourself, in your neighborhood, in your reality. It is patriotism without belligerence.” It is, in effect, love of what makes one’s own place and story distinctive. Each of us inhabits a unique reality (though this does not, of course, mean that there is no Reality beyond our reality). Each of our imaginations is a conglomerate of our particular experiences. I, for example, am a Catholic; a twenty-first-century American who has lived in Colorado, New York City, Phoenix, and Detroit; a woman, a wife, a mother, a poet. That is my imaginative province. It is distinct, in small ways or great, from yours.

Catholicism has a beautiful way of depicting this small-r reality versus big-R Reality. Catholicism says that each person participates uniquely in the image of God. God is infinite; a finite being can reveal only a facet of God’s nature. Each of us reveals a new facet. This is the foundation of the Western teaching that humans have dignity: each human is a unique revelation of the image of God.

This is borne out in the stories of the saints: people who, in the pursuit of God, are willing to give up wealth, power, lands, marriage and sexual fulfillment, children—everything the world says will give you a sense of self. Some, like St. Hildegard of Bingen, spent decades literally bricked into the walls of churches. Some, like St. Francis, wandered the world homeless and impoverished. Yet these saints, each of whom loved and sacrificed for the same thing (God), blaze out with remarkable, even overwhelming individuality. The man St. Francis of Assisi is nothing like the man St. Ignatius of Loyola; St. Hildegard’s life of crafting soaring musical compositions is utterly different from St. Teresa’s of caring for the dying on the streets of Calcutta. But each of them is profoundly self-expressive, because they seek to express not themselves but something far beyond themselves.

These men and women filled and overflowed the borders of themselves, because what they were seeking—God—is beyond any individual imagination. And in giving up their selves, they became truly remarkable selves.

Here is my point: we each inhabit a unique reality in that each of us lives in a slightly different relation to truth and beauty, but the truth and the beauty we are seeking are the same. Weaver added, “Convincing cases have been made to show that all great art is provincial,” because all art reflects “a place, a time, and a Zeitgeist.” All art, in other words, is steeped in the particular experiences of its maker.

Provincialism Under Fire

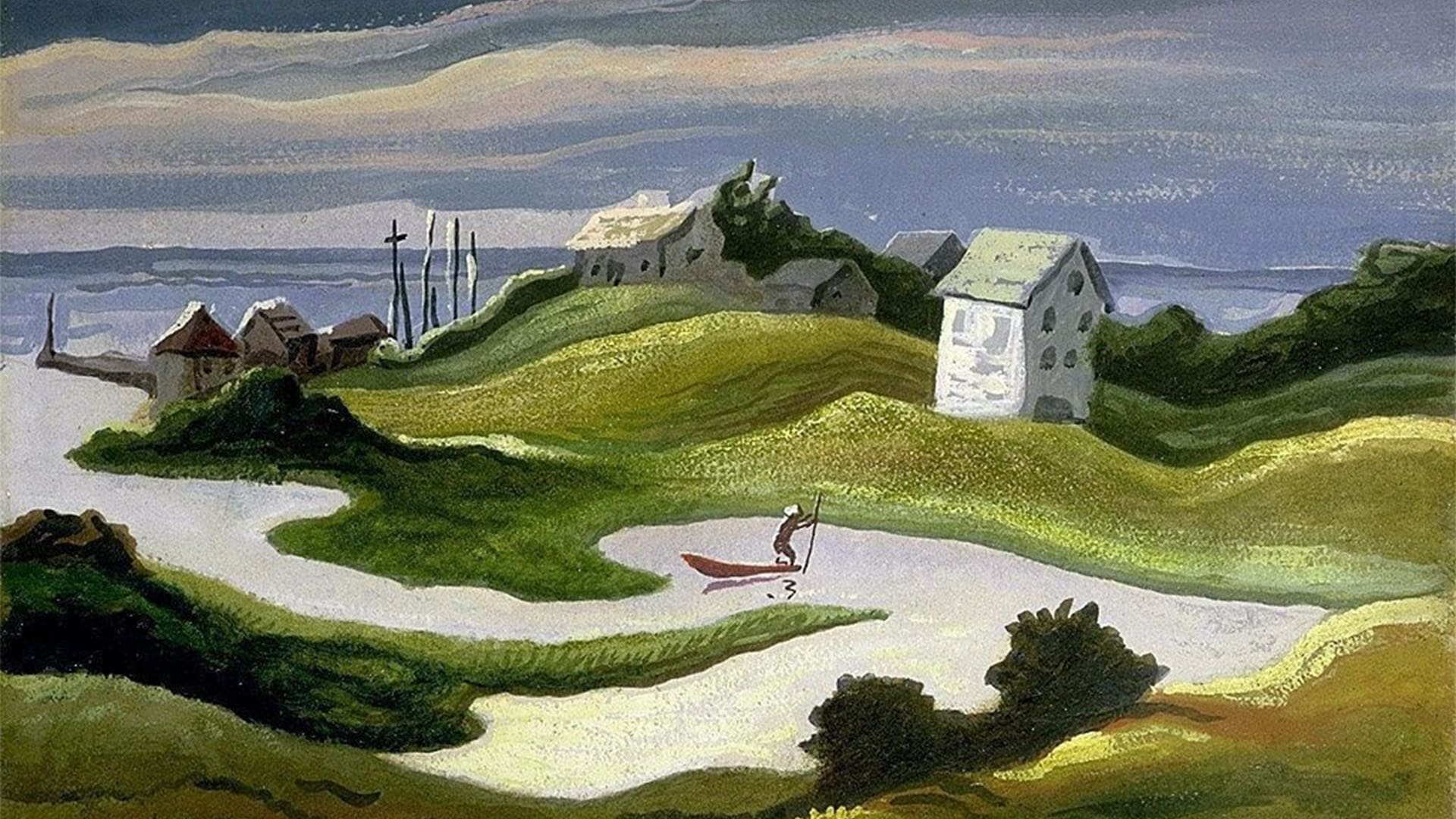

This might seem commonsensical. But it is not. Artists who demonstrate a sincere love of their own place often come under fire. One example is Andrew Wyeth, who created such famous works as Christina’s World and my favorite of his, Tenant House. Wyeth was fascinated by rural America, he was skeptical of the sweeping promises of progressivism, and he believed that the past has much to offer us. Critics excoriated his work and derided him as small-minded, reactionary, trite, uninspired . . . and provincial.

In this derogatory usage, “provincial” occupies the same space as “Luddite,” referring to someone who is entrenched in the ways of his or her place, someone who is somewhat baffled by what Martin Buber calls “the Other.” But if we are honest, who among us is not baffled by the Other? Who is not disturbed, in the same way water is disturbed by the wind, by that which is beyond our ken? Who among us does not look with wonder and confusion at ways we have not walked, signs that we do not yet understand?

There is nothing inherently wrong with being provincial, with drawing our strength from the ground our roots are sunk in. In fact, done rightly, it is a virtue. To be properly provincial—to be struck by the Otherness of a way of thinking—is to say that you have your own way of thinking. To be provincial is simply to say that you love something deeply, that you believe in the loveliness, or the potential loveliness, of a particular place and its particular ways.

In an essay called “The Dangers of Internationalism,” Roger Scruton contrasts what I am calling provincialism with what he calls “internationalism.” Internationalism despises difference. The first impulse of internationalism, when presented with something it does not understand, is to bring the unfamiliar into alignment with itself.

The internationalist, Scruton writes, “sees the world as one vast system in which everyone is equally a customer, a consumer, a creature of wants and needs.” This person, says Scruton, “does not feel at home in any city because he is an alien in all—including his own.”

In art, this means that there are only a very few imaginative signs—and those of the least power—available to the artist. Internationalism tolerates only the most watered-down, insipid sentiments. This is not strictly a contemporary notion; critics as far back as Ben Jonson have associated artistic success with universality, with transcendence of a particular time and place. By this standard, however, some of the finest art in history fails. Think of Milton’s Paradise Lost, crowded with seventeenth-century notions of economics (a ban on usury, for example) and political authority (hierarchy as representative of God), or of Dante’s Divine Comedy, mired as it is in fourteenth-century Florentine politics. Both of these poems require immense legwork for the audience to enter the artist’s province—but once we are there, we behold wonders.

Imagine a particular piece of art, and all the various signs it employs, as a musical note sounded in the open air. On its own, it will dissipate into the expanse of the air. It is the cliffs and hillsides and valleys of our provinces that transform that sound into echoes, echoes that repeat and repeat until meaning adheres to the sound, meaning it did not have before, like in Tennyson’s “The Splendor Falls”:

The splendor falls on castle walls

And snowy summits old in story;

The long light shakes across the lakes,

And the wild cataract leaps in glory.

Blow, bugle, blow, set the wild echoes flying!

Blow, bugle; answer, echoes, dying, dying, dying.

On the vast levelled plains of the internationalist, there is nothing for the signs, for the sound, to play against. There are no echoes, and the art is diminished.

The critics who denounced Wyeth were internationalists. They sensed something real about his work, something grounded, a sense of homeliness that they could not abide. Wyeth painted from a very particular place: Pennsylvania in the mid-twentieth century. He wrestled with life, death, good, evil, salvation, and damnation using the signs of that place. Under Wyeth’s brush, the world shifts and turns; what seems safe and optimistic is revealed to be fearsome, what seems cozy shares a seat with terror, and reality is fine-grained good and evil pressed together inseparably, crushed into very narrow limits.

Critics condemned his choice to work within those limits. But Wyeth’s work has the profound depth and surety that comes of having solid ground under one’s feet. His internationalist critics couldn’t understand that. They had nothing under their feet. But Wyeth knew where he was: he was at home, in his own province, and he had much work to do.

Love Is Always Particular

In The Screwtape Letters, C.S. Lewis touches on the truth that true love is always particular. The devil Screwtape urges his nephew to encourage humans to think well of generalities—humanity or nature or society—but never to attach their love to particular things. “You must keep on shoving all the virtues outward till they are finally located in the circle of fantasy,” the devil urges. “The malice thus becomes wholly real and the benevolence largely imaginary.”

Now, one need not be a regionalist, or an artist whose work focuses on a particular geographic area, like Wyeth, to dwell securely in an imaginative province. Scruton, in the same essay, distinguishes between “internationalism” and “cosmopolitanism.” He describes a “cosmopolitan” as someone who is “at home in any city,” who is able to “appreciate human life in all its peaceful forms.” This appreciation is possible only for the person who believes in his own city, in his own province. His belief in his own land is what makes other lands beautiful. The man who does not love his own land cannot truly appreciate another.

Love shows itself through our wills, and we can only really use our wills on things within our reach. Love is always particular. Our province is the realm in which we can, through our actions, show true love through a movement of our wills and an action of our bodies and souls.

This brings us to an important note: Provincialism is not colonialist. It has no interest in making all other ways and places mirror its ways and places, just as a happy family does not try to make all families identical to it. It is secure in its own happiness. Provincialism loves its own place for its distinctiveness. In fact, the true provincial would be saddened to see the whole world made like her place—or, rather, she would laugh, for she knows the truth that every place is different, and that to try to make one place just like another is folly.

Our province is the realm in which we can, through our actions, show true love through a movement of our wills and an action of our bodies and souls.

G.K. Chesterton writes about this in Orthodoxy. In the following quote, he takes Pimlico, a declining London neighbourhood of his day, as his example; I will substitute “metro Detroit,” because that is where I live. Chesterton says,

It is not enough for a man to disapprove of metro Detroit; in that case he will merely cut his throat or move to Chicago. Nor, certainly, is it enough for a man to approve of metro Detroit: for then it will remain metro Detroit, which would be awful. The only way out of it seems to be for someone to love metro Detroit: to love it with a transcendental tie and without any earthly reason.

That love of place, which Chesterton describes as “the mystic and arbitrary,” is transformative. As T.S. Eliot says in “East Coker,”

Home is where one starts from.

As we grow older

The world becomes stranger, the pattern more complicated

Of dead and living.

Eliot urges us to find a home behind us, a place to “start from,” so that we can begin to follow the intricate play of death and life. That home is our province. Within that province, every person has certain responsibilities—responsibilities to art, yes, but also responsibilities to oneself, responsibilities to one’s own soul and imagination. Each of us has the potential to be a seer of art; this means that we must learn to see. Each of us has the potential to be a hearer of art; this means that we must learn to hear. Each one of us has a province within the realm of imagination, and it is our duty to cultivate it, guard it, and make it beautiful.

Province is a particularly helpful term because it carries a second meaning. For something to fall “within someone’s province” means that it comes under their responsibility. Our responsibility extends only as far as our will; if something is beyond our will (for example, a totalitarian dictator’s action), it is not within our province. It is, however, up to us how we deal with our friends and neighbours, no matter what kind of regime we live under.

Chesterton wrote, “If men love [their city] as mothers love children, arbitrarily, because it is theirs, [their city] in a year or two might be fairer than Florence.” Beauty, and with it art and culture, arises in response to love—love of particular things—not the other way around.

Art is simultaneously an act of love and of responsibility. Accordingly, the insights and signs used by a particular artist are most powerful when those signs come from within that artist’s province—even if that means the signs are unfamiliar to many other people. As we have seen from the staying power of Dante’s Divine Comedy, when an artist loves a particular thing deeply, he draws others into his love. They will learn the signs of his province and take that love with them into their own provinces—both the beauty and the morality of that love.

This essay is adapted from a talk given at the Intercollegiate Studies Institute’s “Art and the Moral Imagination” conference in February 2023.