M

One need only imagine an artistically inclined worker on an assembly line who, smitten by his muse, loses himself in contemplation over the unique and irreproducible features of a particular screw. Such contemplation would clearly be irrelevant to the performance of his job and (certainly if repeated with any degree of regularity) would eventually prevent him from performing his job.

—Peter Berger, The Homeless Mind

Medical students enter the anatomy lab dreaming about “the art of medicine” but graduate residency bewildered because they can’t make sense of themselves as technicians in a profession that once claimed to be a kind of art. As the beloved poet and essayist Wendell Berry might put it, today’s medical trainees struggle to authenticate their wonder. Such disenfranchised expectations are clearly on display in the so-called great resignation, quiet quitting, and burnout phenomenon that continue to plague the medical profession. Many treatment plans have been proposed to counter this, including a renewed focus on the arts. This is hardly new.

The father of modern medicine, William Osler, was still making calls for the humanities in his last public speech in 1919. When Abraham Flexner reformed medical education in his infamous 1910 “Flexner Report,” he neglected to mention the health humanities because he assumed medical students would have already been exposed to such formative work. Like St. Anselm’s description of the theological task, fides quaerens intellectum—“faith seeking understanding”—medicine has long looked to art to seek understanding. But as Berry writes in The Art of Loading Brush, rather than seeking a vague “understanding,” good art seeks “a something.” For when medicine looks to the arts, it often seeks a vague understanding rather than a something that manifests itself in the real work of healing.

I know and believe that the arts change what the doctor does on the ground, in the room with the suffering other. Sitting before art has taught me to sit in silence before the patient, to resist filling dead space with dead words. I literally hold my body differently after meditating on Marie-Michèle Poncet’s sketches made during her time as a patient. Cody Fry’s orchestral cover of the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” has changed how I look out for lonely people. Raymond Carver’s poem “What the Doctor Said” has changed what I say in the room with patients—what questions I’m willing to ask. The artwork of Darian Goldin Stahl, featuring the MRI scans of her sister, theologian and bioethicist Devan Stahl, has moved me to invite my patients to read their scans with me. The list goes on. These artists have remade my medicine; they have remade me.

The arts have cultivated “something” in me just as they do in the moral work of health care, and I want to clarify that “something.” Because, as historian Clark Carlton has cautioned, if all the arts do is baptize medicine with “a series of metaphors, points of view, and attitudes,” then it would seem the arts will do little to inspire a profession desperate for new life and wonder.

There has long been concern that engagement with the arts in health care perpetuates a kind of self-fulfilling feel-good-ism among doctors, galvanizing those who were already reading poetry and looking at art before entering medicine, perpetuating what physician and medical educator Arno Kumagai memorably calls the problem of artistic “entombment, elitism, and entertainment”—clinking wine glasses in private galleries, bowdlerizing the arts as mere entertainment to escape from the work and wounds at hand. As the philosopher Charles Taylor puts it, we “give ourselves frissons [aesthetic goose bumps] while still holding the reality at bay.”

On the other hand, the arts can be a threat to a dehumanized and depersonalized industry because they humanize and personalize. They risk perpetuating daydreaming or distraction in a technocratic system that requires workers to keep their fingers on the scalpel (or on the keyboard).

Systematic reviews of humanities interventions in medical education over the last few years make plain a skepticism over the “contextual significance” of the arts in medicine. “Scattered insights” and “easy generalizations” seem to plague the arts-and-medicine literature. To take just one representative example, in a 2021 comprehensive review in Academic Medicine of 769 arts-and-humanities interventions, only half appeared to have an evaluative component, and the ones that did tended to evaluate only learner satisfaction. The bulk of interventions focused on “making the case” for the arts—a case that, it seems to me, has been made many times without apparent change in “the moral development of physicians.” As philosopher and physician Jeffrey Bishop puts it, medicine has been dutifully taking a “humanities pill” for so long, without obvious benefit, that it suggests misdiagnosis—maybe even mistreatment.

The health humanities may perpetuate the very industrial gaze they propose to heal. To continue drawing on Bishop, artistic representations of patients and their illnesses, regardless of the good purposes for which they were imagined, often function in practice as “interpretive overlays” for the body reduced to a machine. Art interventions that aim to cultivate attention through tours of the art museum, for example, may only further specialize and constrain the medical trainee’s sight, in which students who get better at “dissecting the canvas” become more efficient at dissecting the suffering person. Narrative-medicine interventions, aimed at deep listening, may in the end simply train clinicians to skillfully interrupt their patients, gleaning the information most necessary for efficient billing or quote-mining patients for interesting cases or stories to submit later for potential publication.

Philosopher William Desmond calls this the problem of “serviceable disposability.” The arts are instrumentalized to serve medicine’s ends, and like a used syringe, they become disposable once injected. The current literature on the arts and medicine is dominated by episodic installments that prioritize medical application. The Rhode Island Arts in Health Advisory Group is one example. In 2016, artists, clinicians, community members, patients, and researchers partnered together to complete a comprehensive review of arts-based interventions in health care. After screening over 6,000 studies, they found only 418 met criteria for rigorous medical research. The remaining 93 percent were dismissed as “research waste.” The artists, however, had a different perspective:

Artists on our team prioritized community needs over all other aspects of our work, even over rigor. They pushed hard to have less rigorous studies included, such as work that . . . aligned with artists’ notions of individual and community health. In the end, these were excluded because they didn’t fit strict definitions from public health and medicine. As a result, we discounted meaningful directions for arts in health inquiry. We ignored the artists and the artistic methods to the detriment of our research.

Artistic methods held value outside the constraints of “strict definitions from public health and medicine,” which the authors could only recognize in hindsight. This raises important questions: What is it about such methods that are so readily discounted by medical researchers? Why are artists particularly sensitive to the needs of individuals and the community? What does that mean for the artist’s relationship with public health, clinical ethics, and the art of medicine itself?

I think of the Gospel story in Matthew 26 of the woman with the alabaster jar, who breaks her precious vial to anoint Jesus’s feet with an expensive perfume that could have been sold for more immediate and utilitarian purposes. The disciples complain, “Why this waste?” Yet Christ claims, “She has done a beautiful thing to me.” The effective altruists would not like it.

The health humanities struggle with specifying and making space for “the something” that the arts bring about in the moral work of medicine, while respecting the artist’s work as such—work that surely bears no debt to explain or constrain itself on medicine’s terms. It can be a challenge to proclaim beauty where the industrialist sees waste. Philosopher James K.A. Smith puts it this way:

I crave less explanation and more of the epiphanic insight that comes from being transported by art—a knowledge that doesn’t require ratification in a lab. . . . To recognize flashes of illumination as knowledge, and as a sort of knowledge that eludes empirical measurement.

Or as Giorgio Bordin and Laura Polo D’Ambrosio write in their splendid collection Medicine in Art, “to overcome the restrictions of chronic illness, one must explore dimensions that are inaccessible to rational verification.”

Medicine wants to specify “the something” that the arts bring to healing, but that something can’t be fully named. Art is allusive—symbolic, figurative, indirect, abounding. It helps make what philosopher Calvin Seerveld calls “a billion, semi-fleeting connections” we never could have seen otherwise. For a moment everything feels enmeshed by thick poetry and deep magic, as if promising a grand theory of everything. Beauty will save the world.

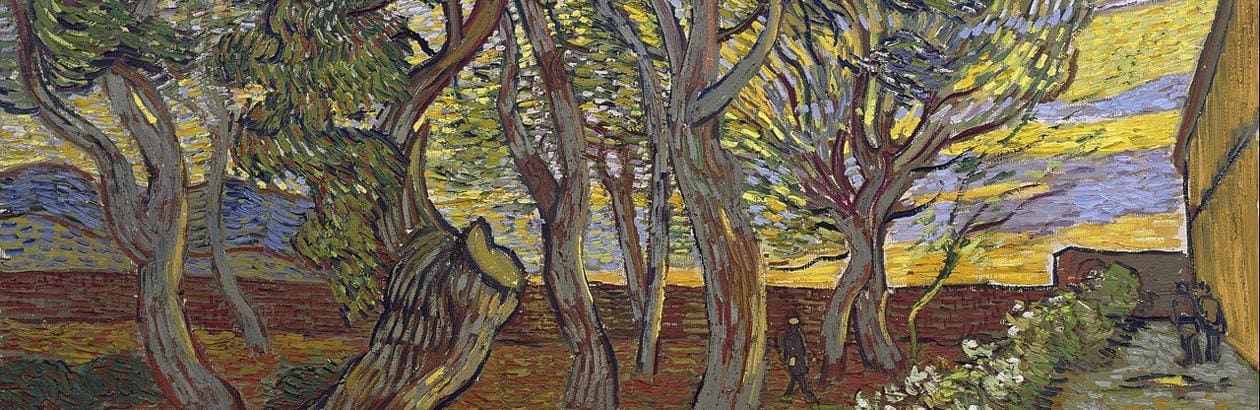

But then art quickly reminds us it is also elusive—mysterious, resisting “strict definitions,” refusing full comprehension. We are dealing with escape artists, difficult to capture, hesitant to reveal what is hidden—like rood screens in a parish church simulating the sun setting behind a thick wood. Or like incense filling a cathedral, stinging the eyes as if intentionally obscuring a clear vision of the Eucharist. The connections that are made cannot be too clear. There is an ineffability at work.

Perhaps the first “something” we can name is the way the arts disrupt and subvert the clinician’s very methods of understanding. Where else can uncertainty become a form of knowing? Where else can silence become a form of deep communication? In a profession that trains its practitioners to seek mastery and clear communication, this can be a strange call.

Consider “Aesthetic Reflection Time,” or “ART,” at Dalhousie University—a reimagining of the standard medical school OSCE (which stands for “objective structured clinical exam”). In a classic OSCE, medical students interact with medical actors portraying future patients to assess their basic interviewing and physical exam skills. But in “ART”—students were asked to interact with works of art. Medical students voiced “curiosity and skepticism” but also “expressed discomfort at sitting alone in silence with visual art.” One student’s response is particularly striking: although “composing yourself is very valuable,” sitting in silence would be “a waste of time in a real [clinical exam].”

It happens to me every week it seems, a patient will share something with me—something painful, something it takes a long time to say—and we will sit together, carefully attentive to the silence, and immediately a new connection will open despite few words being exchanged. Something has become known in the uncertainty. The possibility of solidarity rises out of silence.

That ability to sit quietly—to linger in front of a work of art, waiting for what the poet Sylvia Plath calls “that rare, random descent”—seems to be another one of the specific “somethings” the arts bring to the moral work of doctoring (especially given the average physician interrupts the patient within eleven seconds of an encounter). The artistic posture commands the clinician to look, listen, receive, and surrender—as C.S. Lewis famously put it—standing before the ground of being that is the patient, waiting to receive understanding in a posture of wonder rather than grasp for it in a posture of control.

I think of Hegel, “The owl of Minerva begins its flight only with the onset of dusk.” The fog of indecision between doctor and patient often lifts only after a period of long-suffering attention. Reason watches, collecting data in the daylight. But the wings of wisdom wait for sundown—when the path is dimming yet somehow easier to discern. It is the little way of love that becomes clear in the silver hour.

The wings of wisdom wait for sundown—when the path is dimming yet somehow easier to discern. It is the little way of love that becomes clear in the silver hour.

What of sitting with uncertainty? The typical sense in which medical educators describe the value of the arts to improve a doctor’s perceptive ability is an increased precision to find what one is trained to look for—red flags, pertinent positives, diagnostic clues. Some of this skill becomes automatic and is in fact crucial for developing the “sick or not sick” triage distinctions that all physicians must master. There is a pattern-recognition process that is usually good, perhaps most obviously in emergency medicine. At the same time, some of this automaticity perpetuates the hurried, “cog-in-a-machine” imagination that marks the burnout and cynicism of modern medicine.

The arts can both strengthen the kind of keen vision necessary for a more efficient diagnostic process while also generatively disrupting what has grown rote. This is why philosopher of perception Alva Noë describes art as a “strange tool.” If a scalpel is a tool that extends the abilities of the hand, art is a tool that extends the ability of the eyes by purposely “disrupt[ing] plain looking.”

Here is an example of how this might work in medical education. Physician and medical educator Arno Kumagai directs his students to the short film In My Language by Amanda Baggs, a woman with severe autism. The first half of this film shows Baggs in a series of uncomfortable acts: humming, rocking, rubbing her face with a magazine—all without any narration. What the students see seems to reinforce their assumptions about autism. The art is elusive.

In the second half of the film, these seemingly bizarre and disjointed acts are accompanied by Baggs’s own commentary, in which she makes connections toward a more whole and intelligible story, revealing that Baggs is “not locked within the confines of the self.” The art is allusive. Kumagai prompts his medical students who watch this with questions about communication, translation, privilege, disability, voyeurism—joining a long line of medical educators who train their students not only to look again but to “look beyond the visible.” As Devan Stahl writes in “The Prophetic Challenge of Disability Art,”

Whereas physicians often turn medical images into idols by foisting their own truths upon the image, disability artists help to transform medical images into icons that embody the authentic subject, open up space for sacramental possibility, and invite ontological transformation of the subject and viewer. Unlike idols, icons interrupt the gaze of the viewer.

Icons don’t only interrupt but bring the viewer into the life of the icon. They invite participation and transformation, not mere usefulness toward a clinical end. Instead of seeking “interpretive overlays” for the body reduced to a machine, this disruptive perspective suggests iconic underpinnings—the masonry that supports the patient’s visibility and experience.

To riff on the work of philosopher Natalie Carnes in Beauty: A Theological Engagement with Gregory of Nyssa, an ancient Christian account of the beautiful moves beyond classical aesthetic categories like “disinterestedness,” “fittingness,” and “functionality,” toward a vision of gratuity and fragility. In their humanity, the patient holds gratuitously more than we could ever imagine at first glance. And in their suffering, the patient is more fragile than we may ever know.

I once met an artist who had been admitted for a psychotic episode. The artist shared with me that once his clinical team learned he was an artist, his physician brought him a cup of crayons—a gesture this artist found infantilizing and confounding. He told me, “Art was what I needed to heal, but not then, and not in that way.” When this artist was made patient and powerless, he bristled against his craft being instrumentalized in such a way that made him feel brittle and further displaced. In hindsight he was able to look back with gratitude—even humour—but in the moment it felt like an attack.

Doctors aim to “first, do no harm.” Hippocrates said that the best medicine is often to do nothing. That said, medicine is a practical profession. Phronesis—practical wisdom—is medicine’s “indispensable virtue.” The work of the beautiful and the work of goodness have long been paired in classical thought, raising well-trod questions about the connections between aesthetics and ethics. It is unlikely that the artist’s psychiatrist meant to do harm when offering crayons. But it presses a critical question: How might the beautiful permeate the practical work of medicine with goodness?

The philosopher Jonathan Lear asks a version of this in Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation, his reflection on the fate of the Crow Nation and the possibility of virtue when one’s very understanding of what is virtuous has been devastated. According to Lear, what would be required is a new kind of Crow poet, “a creative maker of meaningful space” who can take up the past and “rather than use it for nostalgia or ersatz mimesis—project it into vibrant new ways . . . to live and to be.”

I take modern medicine—both for patients and physicians—to be a kind of devastated cultural space, in which a radical work of creativity is needed. Radical not because it is new but because it is “rooted,” radicus. Literally in the soil and therefore also “humble,” hummus—in and of the soil.

Whatever art doctors engage, and however they engage it, must increase the capacity for “imaginative excellence” at the ground level of medicine’s enduring challenges of healing—compassion, accuracy, accompaniment, fortitude, precision, presence—what art and film theorist Rudolf Arnheim calls an “intelligent vision” for vulnerability, fragility, finitude, and hope.

What changes in the health humanities in medical education would be required to inspire this kind of imaginative excellence? In Rainbows for the Fallen World, Seerveld explores the makings of an “obedient aesthetic life”—arguing that the formation of such a life cannot be satisfied by adding a course or two in “art appreciation” or starting up a humanities club after-hours.

As one who has experimented with starting both after-hours humanities clubs and underground art appreciation groups in medical school and residency, I can confirm this is true. It isn’t clear to me, after years of both training as an amateur artist and designing health humanities interventions, whether those students and residents who participate in aesthetic exercises practice a medicine that is somehow more just or beautiful than colleagues who “don’t do art.”

But this is clear to me: when group engagement with a work of art or a poem rises above pretense and feel-good-ism and brings hands back to the rough ground of patient care, such exercises have a way of gathering co-labourers to a sacred place, clearing the ground for something to happen. A space is made for arrival and revival. Experiences in the arts and medicine must be anchored in such root work, tailored to the actual embodied experiences of practitioners and their patients in community rather than in generic self-care or arts-reflection skills—valuable as they may be for individualized physician wellness.

Art cannot seek good doctoring by merely assembling a storehouse of private aesthetic experiences. Rather, this work can be an act of taking care and making care in and of itself, especially when intentionally seeking participatory engagement by artists and patients. Darian Stahl’s work in medical book-making, again in partnership with her sister Devan Stahl, is just one remarkable example. Her project “Embodied Books: Binding Together Illness, Art, and Learning” explores the potential of merging text, image, and sensory experience to communicate the lived experience of patients “with the aim of sensitizing healthcare practitioners to the life of their patients beyond the clinic doors.”

The Healthy Housing Omaha LEAD Stories Collaboration is another example—a portraiture, narrative, and print-making collaboration with clinicians, artists, and patients published monthly in the local newspaper of Omaha, Nebraska, to shed light on lead-contaminated superfund sites and substandard housing that poses significant risks for childhood lead exposure. Middle-class black children are three times more likely than middle-class white children to have elevated blood lead levels in this area. As the authors point out, it is literally a black-and-white issue, reflected in the black-and-white woodcut prints published in their newspaper. Here is art that is enmeshed, longitudinal, experimental, and rooted within the very work yet to be done.

I grew up training in art before training in medicine. I love them both, practice them both, and see the two worlds as deeply intertwined. But I’ve learned in my admittedly brief years as a physician that there is a difficult dance between how art seeks understanding and how medicine seeks understanding, between the allusive and the elusive, between strengthening perception and disrupting it, between fostering wonder and tempering control, between practical application and resisting commodification, between entering ambiguity while still offering some assemblance of certainty for patients who, frankly, want to know what the hell is going on.

I think of the twenty-fourth canto of Paradiso, when St. Peter tests Dante on faith and wryly accuses him of circular reasoning: “You call to witness what you seek to prove.” In a lot of ways I am calling to the stand the very thing I hope to catechize and acquit. But it is only under the witness of patients that a doctor can know whether she has cared for her patients well. We might ask patients whether the art-seeking of their physicians has made any difference in their healing.

One of my patients is a gifted visual artist. When we first met, I began asking her questions about her art, rambling about the work and conversations I’m thankful to be involved with between artists, theologians, philosophers, and ethicists, wondering if it would open up some kind of “meaningful space”—and I’ll never forget her gently interrupting me, saying, “That’s very interesting, but you know I’m here because I’m in pain.” She didn’t want to talk art. She wanted a physician. I wasn’t leading an obedient aesthetic life in that moment by shoehorning aesthetics into the room.

Another one of my patients is not an artist. But she came in one day struggling to articulate her loneliness. I was struggling to find the right words to comfort her myself. At one point in our conversation, I paused and pulled up The Prophet Fed by a Raven by Clive Hicks-Jenkins. I asked her, “Do you feel like this?” She immediately became tearful. She felt seen. A work of art made it possible for us to connect and to discuss next steps—what unexpected emissaries might God be using to bring his manna to her in a time of weariness and longing.

I opened this essay thinking about the loss of wonder in medical training—the possibility of growing smitten over a screw. For Berry, wonder is authenticated by “intimate knowledge” and “a sense of the miraculousness of . . . existence.” What beauty must one encounter to foster this kind of intimate knowledge and sense of the miraculous? What forms of medical practice make that intimacy possible? What faith? What love? “Go with your love to the fields,” Berry commands. “Every theory, calculation, graph, diagram, idea, study, model, method, scheme, plan, and hope must be caught firmly by the ear and led out into the weather, onto the ground.” That includes the ideal and the hope of “the art of medicine.” The love of the art of medicine—as well as a love of the arts in medicine—must always lead back to the patient at hand and to the rough ground of their healing.

Perhaps there, the physician can be artistically inclined without being smitten by her muse. She can recognize her patients are not screws and she is not standing on an assembly line. She can contemplate the unique and irreproducible features of a particular patient without losing herself. Such contemplation would clearly be relevant to the performance of her job and (certainly if repeated with any degree of regularity) will help her find understanding.

This essay was originally presented as “Art Seeking (Just) Doctoring” at the 2022 Baylor Symposium on Faith and Culture, “Art Seeking Understanding,” October 27, 2022, Waco, Texas.