I

The type of attention you pay governs what it is you find. (Iain McGilchrist)

I’m a recovering hater of contemporary art; and oh, the fun I had hating it. Like Nicolas Cage piling liquor into a shopping cart in that poignant 1995 chronicle of alcoholism, Leaving Las Vegas, I eagerly amassed examples of the art I hated. The moronics of Martin Creed, the nihilism of Hermann Nitsch, the putridity of Paul McCarthy, the prostitutional antics of Andrea Fraser, the ridiculousness of Richard Prince, and the blasphemies of Matthew Barney, whose aim (one scholar claims) is to “usurp and distort the role of the Creator.” Do yourself a favour and don’t look up any of these artists. I’m still particularly proud of one piece, “The Five Stages of Grieving the Art of Jeff Koons,” in which I lamented, commenting on his 1988 sculpture Michael Jackson and Bubbles, “We get the pietàs we deserve.” Those were my wild days of binge criticism.

I came by my art-hating habit honestly, for it was the hatred of a betrayed lover. I began visiting museums and galleries as a blissfully green art history major at the end of the last century. I learned to adore the way paint could gently pile on canvas and to revel in the jagged dance of sculpture with space, especially in the early evening at an unexpected gallery lining a cobbled street. I had come to believe that materials lovingly conjoined by an artist fuelled by skill and affection ineluctably signalled something more. The space contained by the four walls of a gallery became—if the art within delivered—vastly bigger than the room ever could be on its own. As Jerusalem’s ancient temple signified the meaning of the created world beyond it, so could the surfeit of meaning in a gallery be a key to deciphering beauty in the world as a whole. Galleries were not mere square footage but portals. I trusted that artistic experimentation was a gamble worth taking because the jackpot of beauty—I knew from repeated experience—was a greater payoff than money itself.

I had come to believe that materials lovingly conjoined by an artist fuelled by skill and affection ineluctably signalled something more.

But then I learned that the art-world casino was rigged. One early betrayal was my 2005 visit to the famously exoskeletal Centre Pompidou in Paris. There I saw the “Disfigurement Art” room, the “Violent Procedures Art” room, and the “Pathos/Death” room, all for a steep admission fee. I had come to Paris for beauty, and I found a carefully curated black hole. Another betrayal was the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, a repurposed train station that is something of a Costco of contemporary art. There I encountered Bruce Nauman’s steel temple of despair, an anti–holy of holies with the title Room with My Soul Left Out/Room That Does Not Care. But I wasn’t about to stop caring, so I fired back.

It was easy to hate art, and it was enjoyable. I had been wounded, and I had purpose. “You killed beauty,” I rehearsed to my chosen opponents like Inigo Montoya looking for a six-fingered man; “prepare do die.” This approach to modern and contemporary art is very good for building an audience. Smut sells, especially when it needs to be described in detail to be denounced. If this strategy appeals to you, I recommend titling your debut article something like “Why Elites Hate Beauty,” and you’ll be well on your way. Competing venues—newsletters, X accounts, Substacks—provide such services today, and really, who can blame them? The art world keeps delivering material worth hating, and the bad material is always—like the opening ceremony of the Paris Olympics—the easiest to find.

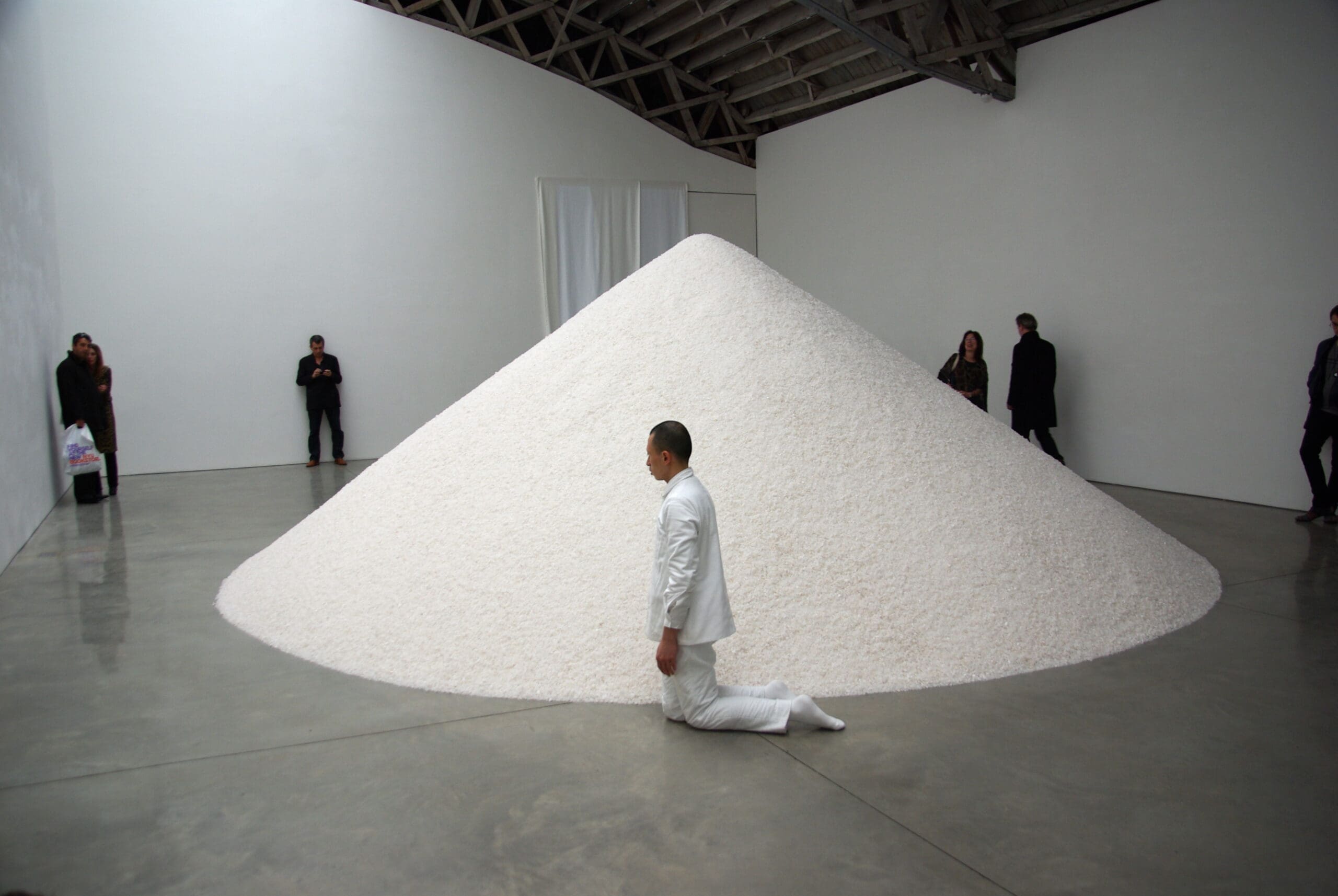

But then something unexpected happened. I kept going to art galleries, mostly out of habit. I suppose I initially hoped to amass more items in my shopping cart of hateable art, which the galleries frequently provided. But in the first decades of the present century, trip after trip to the Chelsea gallery district in Manhattan—an epicentre of what we call “the art world”—wore down my resolve. The posture of criticism grew boring to me. Hate-walking a gallery district, I discovered, wearies the feet. Eventually, I published a piece that explained my change of perspective. In it I described walking in on a performance by artist Terence Koh, who was circumambulating a massive pile of salt on his knees. That afternoon, I reached for my poison pen to denounce such meaningless theatrics, but found it wasn’t there. Instead, with dozens of onlookers, I allowed myself to marvel at this silent protest of a far too noisy world. I think the artist may have even been praying.

That pillar of salt was my turning point, and what an ironic one. Those who continue to hate modern and contemporary art might conclude that, like Lot’s wife, I have become that pillar myself, foolishly looking back at that which is ripe for destruction. Or they might conclude that—unwilling to take a brave countercultural stand—I “sold out to the academy.” Perhaps I had grown gullible. But maybe I was developing discernment. Like Koh penitently circling the salt pile, perhaps I was learning to see differently, choosing (foolishly perhaps) to be salt within the art world rather than raining down critical sulfur. Commenting on Genesis 19, Origen tells us that “salt represents the prudence which she [Lot’s wife] lacked.”

There is no need to arraign artists like Martin Creed, as he does so himself in in formal Thames & Hudson literature. “Art galleries are toilets. Curators are toilet attendants,” he tells us.

It’s not that I gave up my Christian faith and became a believer in the religion of art; still less do I find myself endorsing the art world’s idiotic lockstep politics. Instead, I simply noticed that Martin Laird’s claim that “God does not know how to be absent” applies even to museums and art galleries. Many of the churches of the Chelsea neighbourhood, it turns out, have not yet been gentrified away. Visiting them, I married my experience of beauty in those spaces to the furtive beauty I had witnessed in the galleries. Eventually, the difference between these disparate beauties evaporated, as both pointed to their not-so-secret, ultimate Source. In his medieval German sermons, Meister Eckhart describes the eruption of divine presence as a durchbrechen, a “breaking through.” This can happen anywhere, but the chances of it happening in a carefully curated, mostly silent art gallery, I finally realized, almost double.

While I did not give up the need to be critical, the art world already does much of my job for me. As Pierre d’Alancaisez accurately reports, it is already eating itself. Must I therefore stab at it with my fork as well? Why denounce the Paris Olympics if the Dionysian retinue—as discerning readers already know—eventually rips itself apart? There is no need to arraign artists like Martin Creed, as he does so himself in formal Thames & Hudson literature. “Art galleries are toilets. Curators are toilet attendants,” he tells us. One could take Creed at his word, I suppose. Or one could show how his work—in one instance at least—accidentally preaches a life-giving creed instead.

After my disarmament, I saw things I would never have seen otherwise. Recently, social media was abuzz about a sculpture by David Altmejd titled The Eye (2011), placed outside the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Is it Michelangelo’s David for our time, or does the hole in the torso illustrates C.S. Lewis’s brilliant diagnosis of modern malaise, “Men Without Chests”? I would once have found that a very easy question to answer. But I first witnessed the complaints about the sculpture from a curious vantage point. I had just spent a few hours inside the museum itself. There my wife pointed out to me one of the most stunning annunciations I had ever beheld, painted in 1895 by the Canadian artist Mary Eastlake. In her painting, every summer flower seemed to sing, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord,” while the shade of every tree proclaimed, “The power of the Most High shall overshadow you.”

With this, the annunciation within the Montreal museum, like Aaron’s serpentine rod consuming those of Pharaoh’s magicians, absorbs the ostensibly nihilistic art outside it.

I could conclude from this juxtaposition how far our society has devolved in just over a century. Or I could take the surplus of Eastlake’s account and apply it to the perceived deficit of Altmejd’s. This caused me to look again at The Eye, where most of the chest is actually intact. One might just as well see the sculpture as an image of the collapsed ego. Visage clouded by the futile efforts of weary hands, wings of ambition failed and flightless, all the will has left to do is to open itself to the infinite—that is, to God. Meister Eckhart again: “It is necessary to be a virgin by whom Jesus is received. Virgin designates a human being who is devoid of all foreign images and who is as void as he was when he was not yet.” Those two hands at the base of the fissure might be doing the clearing work that we Christians call contemplative prayer.

“You must know,” continues Eckhart, elucidating Altmejd’s art seven hundred years ago, “that to be empty of all things is to be full of God, and to be full of created things is to be empty of God.” With this, the annunciation within the Montreal museum, like Aaron’s serpentine rod consuming those of Pharaoh’s magicians, absorbs the ostensibly nihilistic art outside it. Altmejd’s sculpture, moreover, even has a liturgical analog. It reminds me of a very similar one on view at Marcel Breuer’s famous St. Francis de Sales Church in Michigan. What seems at first like the empty womb of Mary becomes a stage for the ultimate fullness when—from the proper angle—it frames the eucharistic elevation at every Mass. Did Altmejd intend or expect such sacred connections? I suppose not. But the Montreal museum’s director encourages each viewer to find their own meaning in the work, and so we can respectfully oblige.

Since my Chelsea conversion now more than ten years ago, I have had more than a few bad run-ins with contemporary art, enough to fill a fleet of shopping carts. One afternoon in Chicago, I accidentally stumbled into a show that celebrated abortion—featuring the performance of a woman actively “de-wombing” herself. It was so revolting that I had to excuse myself to weep in the hall. On another occasion at a professional art conference, two lesbian activists disrupted a panel I was attending on art and motherhood. Their performance was so deliberately vile, so calculated to offend, that I won’t do them the honour of transferring the offence to you by describing what they did.

Perhaps Augustine, faced with the Olympics opening ceremony, would have rolled his eyes and kindly sent Piche (the bearded drag queen) a fresh can of Barbasol.

As some would have it, refusing to call out such atrocities (which, please note, I just did) is a form of complicity. If only the decent people of the world would blow the whistle on such things, the corridors of high culture would be cleansed. But as absurd as it would be to endorse or admire such inanities, art-world idiocy deserves no more attention than it has already received; such folly is galvanized by widescale outrage. Augustine was once called on to endorse the efforts of his fellow Christians to destroy a statue of the pagan god Hercules, whose beard had already been chipped off. Here was his reply: “I think it was a much greater humiliation for Hercules to have his beard shaved off than to have his head cut off.” Perhaps Augustine, faced with the Olympics opening ceremony, would have rolled his eyes and kindly sent Piche (the bearded drag queen) a fresh can of Barbasol.

Offence is the most normal and natural response to deliberate provocations, just like it would be natural for most of us, on seeing an open wound or streaming blood, to grow queasy. But a physician overcomes those instincts to impart healing, and perhaps the same service is required for some of us who are called to engage contemporary art. As T.S. Eliot put it nearly a century ago in After Strange Gods,

[Blasphemy] is a very different thing in the modern world from what it would be in an “age of faith.” . . . Where blasphemy might once have been a sign of spiritual corruption, it might now be taken rather as a symptom that the soul is still alive, or even that it is recovering animation: for the perception of Good and Evil—whatever choice we may make—is the first requisite of spiritual life.

In the same lectures, Eliot rightly points out that mere “spirituality,” or the flirtations with it that reworking of religious imagery might represent, is obviously inadequate. But it is a start.

Much more than a start, in fact. In my art-hating days, I never stopped to consider that the Christian cataloguing of art crimes might actually reinforce a lingering secularization that has long since expired. Bumbling attempts at blasphemy may steal fleeting global attention, but meanwhile, the de-secularization of the art world has been happily performed by high-profile defectors within the comfortable confines of the art world itself. It turns out God didn’t need a crack team of intrepid Christian critics and art historians to get the job done, even if we still have our own little part to play. Like Gideon up against the Midianites, all we believers had to do was blow some trumpets and smash a few jars.

One summer in Berlin, a city that claims to be the “atheist capital of Europe,” I witnessed all such secular pretensions collapse. I was there for a conference that brought theology and art into conversation, and each of the artists who participated—major, not minor, figures in the Berlin cultural pantheon—quickly found themselves asking downright theological questions about their pursuits. As my friend Jonathan Anderson put it, it was a delicate matter of transposing what they called the “accidental” into what theologians call the apophatic. When the missing religious vocabulary was provided, what these artists were up to—by their own admission—was more adequately revealed.

A show’s presumed meaninglessness, I learned, was not a sentence to be issued but a bluff to be called.

Consequently, when our group returned to Costco—that is, when we visited the Hamburger Bahnhof, where I had encountered Nauman’s anti-temple years before—the venue was transfigured. A show’s presumed meaninglessness, I learned, was not a sentence to be issued but a bluff to be called, because the Author of meaning is as present within the walls of a gallery as anywhere else. How I wish Nauman’s room was still on exhibit, as I could have slipped into it defiantly to pray. But we found something even better.

Once I would have dismissed Anselm Kiefer’s Shekinah, a bridal dress pierced by shattered glass, as trendy drivel. But now I can see what is actually there: the ten sefirot of the Kabbalah, signifying divine presence, confidently rising from the shards. The sculpture reveals the glory of God far better than any flatfooted biblical illustration. “There is nothing that is not pervaded by the power of divinity,” wrote the sixteenth-century Kabbalist Moses Cordovero: “If there were, Ein Sof [the first sefirot] would be limited, subject to duality, God forbid!” God’s glory emerges in Kiefer’s sculpture the way we see it in life, and the way Jewish mystical wisdom teaches that it does—from the last sefirot, Malkuth, the Shekinah, the earthly bride in God’s cosmic wedding. This is not a terrible but a tender emergence from within the damage of our deeply wounded world.

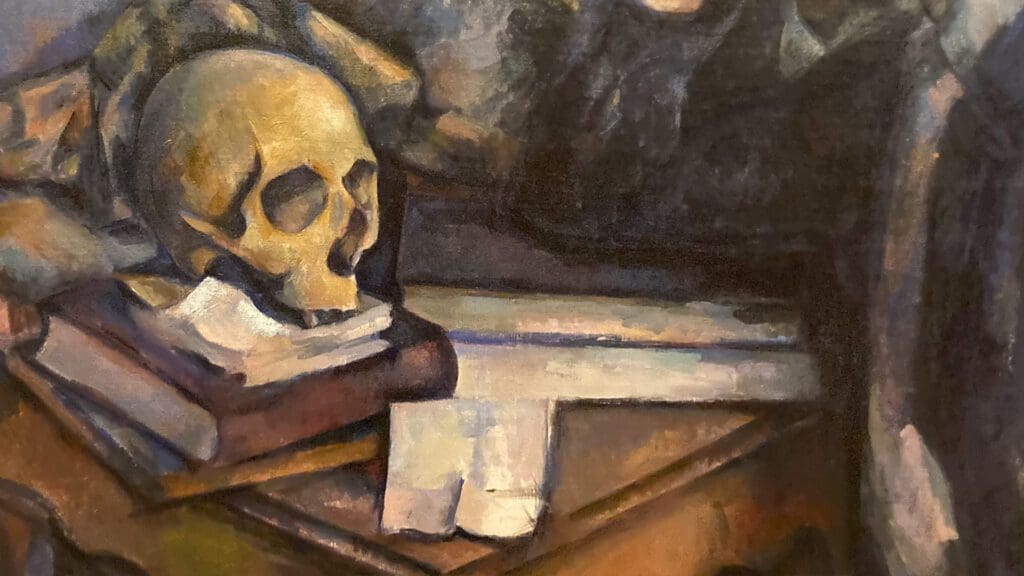

Looking back on my addiction, I think that one of the reasons I began to hate contemporary art is that I could not stomach those wounds. I had learned to love and expect beauty, as I should have, but I was not prepared for the fact that art exhibitions might also expose and lament. To borrow from Martin Luther, I was—when it came to viewing art—an art critic of glory, not an art critic of the cross. In other worlds, while visiting galleries, one should be prepared not just to celebrate but also to grieve. I had already learned this posture thanks to my habit of churchgoing. The liturgy mingles doxology with penitence, so the transfer of these sensibilities to culture at large was thankfully possible. When we are equipped with such sorrow, the imprisoned holy is far more detectable. As Pierre Teilhard de Chardin put it in The Divine Milieu,

Nothing here is profane for those who know how to see it. . . . The world, this palpable world, which we were wont to treat with the boredom and disrespect with which we habitually regard places with no sacred association for us, is in truth a holy place, and we did not know it.

That summer, Europe’s presumably most secular city, as filled with prominent churches as is the neighbourhood of Chelsea, became as sacred as Jerusalem itself.

To borrow from Martin Luther, I was—when it came to viewing art—an art critic of glory, not an art critic of the cross.

True enough, Berlin’s art culture today—Jason Farago explains—is paralyzed by political demands. But it was too late for this to be my sole conclusion. The city had already imparted its lessons, giving me enough confidence to take the attitude back home. Returning to my native collection at the Art Institute of Chicago, as I walked through the galleries of the modern wing, I realized for the first time that Renzo Piano, its architect, helped design the inside-out Centre Pompidou that so offended me twenty years ago in Paris. But the mature Piano had learned discipline and restraint, which is what makes the modern wing such a successful venue for exhibition.

Piano’s wing was a fitting stage for one last confrontation with my old art-hating habit. I entered the venue’s notorious second floor and braved the Jeff Koons room. Yes, I knew that Koons deliberately mangled Leonardo da Vinci’s great painting of John the Baptist with a dumb, derivative sculpture. But that is not all Koons did. It seems the artist had tired of blasphemies just as I had tired of exposing them. Some of his reworkings could even be construed as reverent.

I walked up to one of his mirrors, deliberately patterned after da Vinci’s The Virgin and Child and St. Anne at the Louvre. I had known of it for years and had mocked it as New Age “everyone is God” twaddle. But I had never dared to use it. In Leonardo’s painting, Jesus looks back to his mother and grandmother, as if to say with delight after a tussle with his prize, “Look what I found.” Cognizant of the original, I angled myself so that I saw my own reflection not as Jesus (delicately placed flecks of gold over the eyes actually prevent that association) but instead as the lamb that Christ was rescuing.

It seems the artist had tired of blasphemies just as I had tired of exposing them.

Art-world chicanery is real, and the political groupthink of most of the creative class is amusingly banal. Truth be told, the local art culture of smaller towns is frequently preferable to the established gallery scenes in the world’s major cities. But let me wax pious anyway: What if Christ had looked on me the way I had once looked on the art world? Fortunately, he saw someone worth saving instead. That, I suppose, is the job of a good critic. To see the entire art world in Koons’s mirror of the lamb, to see it as worth saving, even if the rescue involves a tussle. To say “Look what I found!” to those who don’t expect much from the art world. May God forgive the parts of my heart that wish it would stay in hell.