We’re often asked, “Where did the Work Research Foundation come from?” Or, “How did the Work Research Foundation get its start?”

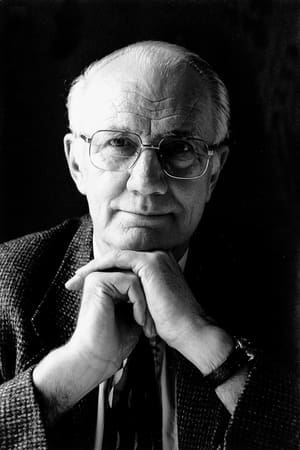

Like so many institutions, the Work Research Foundation started as an idea—the notion of a Christian research organization that would begin its work at the level of worldview. Born in the Netherlands in 1931 and an immigrant to Canada in 1948, Harry Antonides saw Canada’s need for a think tank that would pose critical questions to challenge the modernist-liberal hegemony of thought in this country. His vision didn’t remain a mere dream. Mr. Antonides sought to recognize common intellectual ground, and to elaborate on public life and public policy in the Canadian and North American context. From 1974 to 1997, Harry Antonides took a notion and built it into the Work Research Foundation. We sat down with “Harry” in April 2006.

CM: At the dawn of what is now the Work Research Foundation, what were you thinking?

HA: I became more and more aware that we needed to think more deeply on the basic reason for our existence—the worldview that we’re guided by.

In 1974 we decided that we should establish an organization that specialized in research at the level of worldview: a basic, biblical way of looking at labour relations, but also more broadly at the context and the society in which we lived.

CM: What were your goals and motivations?

HA: Our purpose was to carry on a program of research and education on a Christian view of economics and industrial relations, in which we published papers and promoted Christian insights and attitudes.

Externally, we were motivated by a keen sense of the need for an alternative view of our context—our political and economic lives, but particularly our work lives. The existing approach was governed by a rather materialistic and adversarial approach that was destructive to both workers and employers.

Internally, and particularly with this new research organization, we wanted to work out the implications of a Christian starting point: that we are made in the image of God, created for His service, and to be of service to our neighbours, particularly in the workplace.

CM: Who were your inspirations along the way?

HA: Bernard Zylstra was a close friend of mine, and a professor of political theory at what is now the Institute for Christian Studies. He was a keen articulator of a Christian worldview, and how it plays out—or should play out—in the realm of politics, economics and labour relations. He was a great encourager to me.

One book from the 1950s that was very influential was Hendrik Van Riessen‘s The Society of the Future. It promoted a very helpful insight on a principle that can undergird our culture: sphere sovereignty. Van Riessen spoke much about the two elements of freedom and responsibility, and how most people are so preoccupied with their own gratification that they ignore their responsibilities to God and to fellow humans. Within the notion of sphere sovereignty, we could find a more harmonious relationship between freedom and responsibility. Of course, we tried to particularly work this out in the sphere of labour relations and management.

Another very important inspiration came in the person of Dr. Evan Runner, a professor of philosophy at Calvin College but also a mentor for us. He worked out a very exciting, biblical idea of our being responsible as workers and as managers in an age of a great deal of irresponsibility and conflict. What he said lies behind much of the inspiration for the Work Research Foundation.

CM: What continuity do you see between your vision and what the Work Research Foundation is doing now? What are the discontinuities?

HA: I have to emphasize that I’m extremely pleased to see how the work we began, in all humility and with very limited resources, has expanded in the next generation. When I see the publications that are produced now, the special events organized, and the leadership training, I see the organization blossoming in a way that we couldn’t foresee at the beginning.

It’s not our cleverness, or our effort, that brings about good results. It’s the Lord’s blessing, and his faithfulness in the lives of our organizations, that brings people together for such a task.

CM: Where do you see broader Christian cultural engagement going in our time? What are the biggest opportunities and challenges?

HA: One of the facts of life is the reality of secularization—the notion of human autonomy. That is so prominent now that we can think of it as the attempt by Western culture to cut off its own spiritual foundations and roots. That’s the really big challenge we face.

What do we do about it? Do we despair, and say there’s nothing we can do? Some Christians are willing to just sit and wait for the time of the Lord’s coming. But is it yet possible to raise a Christian voice in this age?

Our advantage is that we still have the freedom of religion, and to a very large extent the freedom of expression and the freedom of organization—the WRF is an example of that. We should never take for granted the space and freedom we now have.

We are cutting off our roots—a form of suicide. But it’s still possible for Christians to be an influence for good. I think it means we have to really think about how we can strengthen the institutions of a wholesome and normative society. One of the indications of a secular society is the breakdown of institutions—the loss of respect for institutions, for the authority of parents, of managers, of trade unions, of teachers, of churches. So what we need to do, and what the WRF is attempting to do, is to think about first things: going back to the norms for institutions.

That’s how I would describe the task of any Christian organization that seeks to be a cultural influence. Seeking renewal of institutions means obedience to the biblical, God-given norms that exist for them all, from families to corporations.

CM: Where do you see gaps in cooperation between institutions?

HA: One problem in the Christian community is that we are so individualistic, we are so focused on keeping our little organizations going, we often lack the big picture. I’m not talking about eliminating the boundaries between various organizations like churches, companies and volunteer organizations. I mean we should be united in our calling to serve the Lord wherever we are, and we also need to find ways to interact with each other—as churches, families, companies, volunteer organizations, labour unions, and organizations like the Work Research Foundation that seek to be facilitators of cooperation among Christians.

CM: What does the present generation need to teach its grandchildren, the way you taught your generation’s grandchildren? How do we build legacy for those after us?

HA: The Bible gives us the message of continuity: listening carefully to the abiding truth of the Scriptures, summarized in Jesus’ command to love God above all, and neighbours as ourselves.

We must remember that each generation must have the freedom and opportunity to respond to the peculiar, new challenges they face. In the past, we thought we had to pass on the rules, the ways that things should be done. That’s the wrong way of doing it.

What we must do in this generation is seek to instill in our children a desire to be faithful to the Lord’s calling, in whatever place and whatever time we are. Don’t tie down the next generation with rules and regulations, but neither tell them that there are no norms and you can do whatever you please. They must do as the Lord pleases, and we must trust that the Lord will provide the guidance of His Spirit, and will be part of that continuity.