Silence is God’s first language; everything else is a poor translation. In order to hear that language, we must learn to be still and to rest in God.

—Thomas Keating

I

I recently stumbled on a Christian movie website that might easily be mistaken for Netflix, Hulu, or any number of other mainstream platforms in both its design and its content. Among other things, the website Faith Film Fans lists a wide variety of upcoming theatrical releases. Since most of them don’t immediately scream “Christian film,” it’s easy to forget you’re browsing faith-based content. This is just one sign of how far the Christian film industry has come into the mainstream while, ironically, church attendance has declined across the United States.

The appetite for Christian-themed entertainment shows no signs of letting up, with several major releases last year. These include Average Joe, which follows the true story of a high school football coach who fought for religious freedom after being fired for praying publicly; White Bird, about a grandmother who reveals how she was sheltered from danger in Nazi-occupied France by a boy whose mother risked everything to protect her; and Brandon Lake and Phil Wickham Present: For the One, documenting the worship leaders as they take audiences behind the scenes of their Summer Worship Nights tour.

Soon to begin its fifth season, The Chosen, which has become a global phenomenon, recently enjoyed its very own convention in Orlando, Florida. For ChosenCon, fans gathered much like they do at major pop-culture events like Comic-Con. The immersive experience, which included interactive exhibits and insider discussions with cast members, demonstrates just how closely Christian media has aligned with and adopted mainstream industry practices.

But Christian cinema’s convergence with Hollywood conventions is a double-edged sword: while it has allowed faith-based media to reach wider audiences, the focus on messaging and the favouring of commercially viable content overlook the deeper, non-verbal dimensions of faith. Some filmmakers choose a different path. They use silence or near silence not just as a space between sounds but as a tool to heighten awareness and create opportunities for personal insight, mining the riches found in moments of quiet, mystery, and spiritual stillness that transcend words. These aspects of filmmaking are vital, and they challenge reductive stereotypes of what it means to be a Christian.

In an era when noise fills every corner of our lives, the gift of silence often goes unnoticed. We thrive on stimulation, and amid the buzz of notifications, the hum of traffic, and the barrage of images on screens, silence, with its offer to pause for introspection, can feel like a fleeting refuge. Our movies mirror this frenzy. The lion’s share of ticket sales usually goes to blockbusters filled with explosive soundtracks, rapid-fire dialogue, and nonstop action. Even the genres that are quieter than action-adventure, like romantic comedy and drama, still depend on sound to steer our emotions.

As with meditation or prayer, silence in film can lead to a heightened consciousness as our attention is drawn inward and we become anchored in our embodied existence.

Yet, in this sea of noise, silence is a vital element of film grammar, and its effective use prompts us to slow down and ground ourselves in the here and now. This awakening of present-moment awareness in the context of what’s unfolding onscreen resonates in a spiritual dimension. As with meditation or prayer, silence in film can lead to a heightened consciousness as our attention is drawn inward and we become anchored in our embodied existence.

Many of the cinema’s most renowned filmmakers have made use of silence or near silence to create tension, heighten emotional impact, emphasize isolation, or underscore moments of existential significance. I’m readily reminded of great moments in the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, Stanley Kubrick, Jean-Luc Godard, and Robert Bresson. In the popular movies of today, silence typically serves to amplify drama. And in recent years the widely popular A Quiet Place film series has raised the bar on how silence can be used to generate suspense and terror, pushing the technique to its fullest potential.

My own experiences with silence, solitude, and simplicity on the contemplative path, alongside the influence of meaningful films that use silence to deepen their impact, has fuelled my interest in the spiritual potential of filmic silence. I’ve often wondered whether this silence can do more than provoke existential reflection. Can it awaken spirituality?

Two films from recent decades exemplify how it can. In each, silence serves as the vehicle for both the experience of heightened awareness and insight into the riches of Christian tradition. In Philip Grӧning’s Into Great Silence (2005) and Paweł Pawlikowski’s Ida (2013), silence functions as both cinematic device and thematic core in the exploration of the interior dimension of Christian ascetic life. And significantly, both films create meditative experiences through a thoughtful approach to aesthetics. They transform cinema into a mirror that reflects the stillness of spiritual contemplation.

Into Great Silence is a documentary that offers a rare glimpse into the secluded life of Carthusian monks living in the Grand Chartreuse, or “mother house” of the order, hidden away in the French Alps near Grenoble, France. Filmed over Grӧning’s six-month stay in the monastery without a crew or artificial lighting, it captures the monks’ daily prayers, rituals, everyday tasks, and occasional outdoor excursions. The Carthusian order, founded by Saint Bruno of Cologne in 1084, combines hermitic and communal monastic traditions. The monks live in near-constant silence and solitude, gathering only to chant the Divine Office and share a silent meal on Sundays. The film’s minimalist style replicates their austere existence, portraying moments of quiet labour that include tending gardens, chopping wood, and meditating on Scripture.

In addition to its unusual subject, what sets Into Great Silence apart is its refusal to rely on conventional documentary techniques—there is no narration, score, or archival footage. Instead, the bare essentials of filmmaking are employed to immerse viewers in the daily and seasonal rhythms of monastic life, collapsing the divide between observer and observed and creating an experiential shift as the film transforms from a documentary into a sacred journey. Silence—the true heart of the film—goes beyond the simple absence of sound; it becomes a reflection of the monks’ spiritual practice, embodying a profound stillness that speaks to the essence of their religious life. Through an economy of form and concentrated attention on the particulars of monastic life, Grӧning invites the viewer into the monks’ mystical depths.

Ida (2013), set in 1960s Poland, follows a young novice, Anna, who is about to take her final vows to become a nun. Before doing so, she is instructed by her convent’s mother superior to visit her only living relative, her Aunt Wanda, a former Communist prosecutor. When they meet, she learns from Wanda that her real name is not Anna. She was born Ida, she’s Jewish, and her parents were murdered during the Nazi occupation. Together the two women embark on a journey to uncover the fate of Ida’s family, confronting painful truths from the past. Shot in stark black and white and framed in 4:3 aspect ratio, the film recalls the style and atmosphere of 1960s European cinema and delves into themes of faith, identity, and historical trauma. As Ida grapples with her newfound heritage, she must also confront her commitment to her religious calling, which leads to a deeply personal spiritual journey. All this is set against the tragic backdrop of a nation’s collective suffering.

Ida, like Into Great Silence, is grounded in silence, stillness, and solitude. The film’s austere approach, marked by slow pacing and long pauses, limited dialogue, static shots, and extended silences, draws viewers into a state of stillness. Pawlikowski achieves a minimal naturalism that hearkens back to Italian neorealism by stripping away cinematic excess and heightening the impact of subtle sounds, such as the clinking of spoons at a convent dinner or the gentle murmur of the countryside. The restrained camera movement and long takes focus our attention on crucial details so that we have no choice but to dwell on each moment. This deceleration of time mirrors contemplative practices, where silence is a constant presence. The minimal soundscape amplifies the film’s quietude, allowing the absence of noise to become palpable, paralleling Ida’s internal journey of faith and self-discovery.

As with Into Great Silence, Ida’s use of silence and near silence operates on a sensory and experiential level, distinct from the symbolic function of silence within the narrative. While the filmic silence symbolizes Poland’s unspoken traumas, as well as the spiritual void Ida confronts as she wrestles with her identity and calling, the viewer’s experience of the film’s silence is immersive and immediate. The film engages us sensorially through its pacing, stillness, and atmospheric sounds, inducing a meditative state rather than exclusively prompting symbolic interpretation.

Thus, in both films, silence does more than represent thematic elements—it actively invites the viewer into an encounter with stillness. This experiential use of silence transcends documentary and narrative meaning and draws the audience into a shared space of presence, involving the body and senses in a way that suggests contemplative prayer. The viewer’s encounter with silence is one that is lived and embodied, distinct from its formal role in the film’s language.

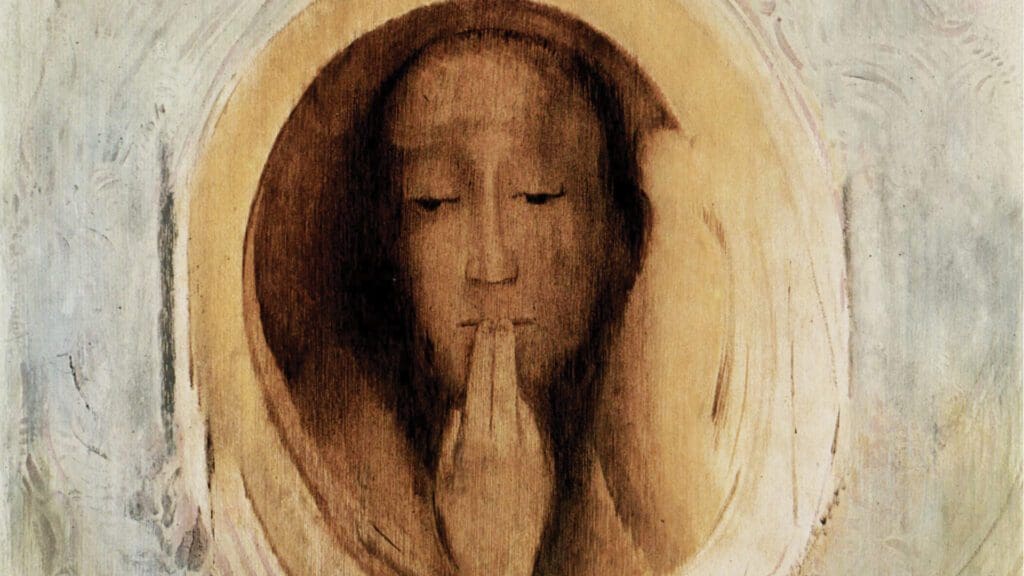

Silence has deep roots in Christianity, tracing its origins from Jesus’s own experiences of solitude to the desert mothers and fathers in the early third century to later monastic traditions where it has served as a pathway to deeper communion with God. It has been embraced by Eastern Christianity from its beginnings, and in Western Christianity it has become a hallmark of the great mystics. Contemplative prayer in its various forms emphasizes inner stillness and the quieting of the mind to enter into the presence of God. Words and images are transcended in the search for the divine. This kind of prayer is rooted in apophatic theology, which focuses on negation, seeking to encounter God beyond all human concepts or forms. Sacred stillness allows for a deeper attunement to the unfolding of God’s presence, and silence becomes a space where divine and human meet.

Yet, in many contemporary Christian spaces, this tradition of silence has been overshadowed by the fast pace and constant stimulation of modern life. While megachurches are the most visible examples, many churches, regardless of size or denomination, emulate the model of crowd-pleasing simplicity, easy messaging, and charismatic leadership. They aim to stimulate their congregations with multimedia presentations; pop-style, energetic worship music; and dynamic preaching that mirrors the entertainment-driven culture of the secular world. Services are characterized by a brisk tempo, with quick transitions that leave little room for contemplation or stillness, the noise and activity crowding out opportunities for the quiet prayer that has always been important to spiritual life.

Through Into Great Silence’s stark realism and Ida’s introspective narrative, Christianity’s forgotten spiritual heritage is revived and brought into the cultural conversation in fresh and unexpected ways. By immersing viewers in extended moments of quiet, these films provide cinematic and spiritual nourishment in equal parts. Their integration of silence augments their formal artistry, rendering them innovative in terms of cinematic language, but their interplay of sound and silence is also a manifestation of Christian tradition. It’s this groundbreaking synergy that makes them both great art and spiritually rewarding experiences that nurture a contemplative disposition.

Both films have been awarded multiple honours, with Ida even winning the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 2015. The critical success and popular attention these films have garnered signals a desire to reclaim silence as a vital component of personal and communal spiritual practice and suggests that modern society is becoming increasingly aware of its absence and the need to reintegrate it into daily life.

What we get from today’s Christian movies is altogether different. Like the services and programming many churches have adopted to fit a consumer-driven model, these films are filled with noise and activity, offering little space for stillness.

But is this any surprise? Although faith-based films encompass a broad spectrum—from the inspirational drama to the biblical epic to the politically driven documentary—most of them rely on Hollywood’s conventions in terms of storytelling, emotional appeal, and production values. They adopt familiar narrative formulas to reach a broad audience. To illustrate, let’s consider a few examples.

Angel Studios’ controversial Sound of Freedom (2023) is replete with all the ingredients required for a solid action thriller, including suspenseful pacing, emotionally charged storytelling, dramatic sequences, chase scenes, and a clear-cut, good-versus-evil narrative. One reason it resonated so strongly with faith-based communities—becoming the highest-grossing indie film since 2019—was its success in presenting intense subject matter from a Christian perspective within the framework of a popular film genre. The movie shares many characteristics with other major films: a determined, relentless hero fighting against human trafficking (e.g., Taken), exploitation of vulnerable populations in conflict zones (e.g., Blood Diamond), complex moral choices in a corrupt system (e.g., The Mule), and a vigilante justice theme that focuses on moral responsibility (e.g., The Equalizer).

Like many Hollywood films, Sound of Freedom builds tension around a heroic protagonist, in this case a US federal agent (Jim Caviezel of The Passion of the Christ fame) who embarks on a rogue mission to rescue children from human traffickers in Latin America. Its satisfying moral resolution is the stuff of most mainstream thrillers. The use of well-known actors (including Mira Sorvino and Bill Camp), high production values, polished cinematography, and clever marketing strategies further solidified its appeal for a mass audience.

Or take 2018’s I Can Only Imagine, another hugely successful Christian movie. In many ways a typical inspirational biopic, it centres on a personal transformation story—Bart Millard’s journey from trauma to triumph—told in a way that is both emotionally stirring and relatable to a broad audience. Character development and a predictable narrative trajectory are driven by uplifting music, dramatic confrontations, and feel-good storytelling that ends with a clear resolution. Like another, better-known hit of that year—A Star Is Born—it concerns a musician facing personal and professional struggles while underscoring the importance of relationships and the experience of redemption in the context of the creative life. As a heartfelt story about overcoming adversity and chasing dreams, it also echoes The Pursuit of Happyness and other popular movies centred on the theme of perseverance and the value of family.

As we mature spiritually, we need films that can continually challenge, inspire, and awaken us. Such films help ensure our souls are fed.

And of course we have The Chosen, which, like any miniseries, is heavy on dialogue and action. This, despite Jesus’s inclination for silence during pivotal moments of his ministry, such as in the wilderness (Luke 4:1–13), before his accusers (Matthew 27:14), and on the cross (Matthew 27:32–46). The serialized storytelling format comes complete with episodic arcs, cliffhangers, and character-driven plots—all aimed to keep viewers engaged over multiple seasons. A unique feature of this Gospel retelling is the expanded backstories of many of the disciples, such as Matthew, Mary Magdalene, and Simon Peter. Following on this premise, fictionalized dialogue becomes central to the progression of each episode, while non-biblical characters provide narrative conflict and help depict the world in which Jesus lived. Events told in the Gospels are dramatized in ways that fit the episodic structure of the show, and its pacing balances intense moments with more intimate scenes, mimicking the approach of other popular series that highlight the human dimension behind historical events.

I don’t wish to suggest there’s no place for films such as these. There is, just as there’s a place for lessons geared to those who are young in their faith. But as we mature spiritually, we need films that can continually challenge, inspire, and awaken us. Such films help ensure our souls are fed.

Notably, in a couple of recent films with religious themes, silence has been used in ways that subvert Hollywood’s usual formulas. In John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary, themes of guilt and redemption surround the personal struggles of a man trying to maintain his faith in the face of overwhelming cynicism and violence. Silence manifests itself in the quiet dignity of Brendan Gleeson’s character, Father James, as he confronts a death threat and wrestles with the weight of sin and forgiveness. Sarah Polley’s Women Talking centres on the moral and ethical dilemmas of confronting abuse, justice, and autonomy in a tight-knit but oppressive religious community. For the Mennonite women at the heart of the film, silence becomes a form of resistance, allowing them to challenge the forces that seek to suppress them.

So, silence is important in these films, each of which is a powerful exploration of religious life. Yet Calvary and Women Talking both revolve around human interaction and societal issues, not spiritual experience.

A cinema rooted in silence amplifies the medium’s power to transport us beyond ordinary time and space. The rhythmic interplay of image, sound, and silence allows us to explore reality from shifting perspectives as a film’s mechanics and our bodily senses synchronize. Rather than passive absorption, our attention is directed inward. The creative use of silence or near silence intensifies our focus on presence, and in this sacred, framed space, time is suspended. Heightened awareness arises from both the structure of the moving image and our own active yet unintentional involvement with it.

In contrast to conventional, mainstream formulas with predictable arcs and dialogue-heavy scripts, the use of silence or near silence provides creative opportunities for formal and stylistic innovation. This can lead to more interesting and original films.

Such an approach subverts the mainstream current of both cinema and Christianity, reshaping both landscapes. Christian films of quietude and stillness have the potential to bring to the forefront an essential dimension of Christian faith that is being rediscovered and revitalized. For mainstream Christians, this new contemplative focus offers a way to cultivate a more intimate, transformative relationship with God. For non-Christians, filmic silence can produce an experience that helps overcome stereotypes of religious life. Films structured in a contemplative way offer mainstream audiences a glimpse into the rarely acknowledged spiritual treasures within the tradition.

Today’s fast-paced, noisy world—and the movies that contribute to it—makes the appeal of silence powerful. We are bombarded by external noise and the internal chatter of our thoughts, which cloud our ability to see and experience what’s right here and now. Silence, as an aesthetic and a spiritual choice, offers clarity in the fog of distractions. Its creative and skillful use in film allows space for viewers to listen attentively to themselves, to the world, and to God, reflecting the experience of the prophet Elijah, who found God not in the wind or fire but in a gentle whisper. When Christian filmmakers embrace silence as a vital part of their religious tradition, they can use it with intention to communicate more than words ever could, perhaps inspiring audiences to seek out quiet moments where they, too, might encounter the divine.