M

Many are making a case for what the church needs more of—more justice, more doctrinal clarity, more anti-racism, more “non-duality,” more women, more men, more moral rigor, more unmerited grace, more silence and contemplation. What I think we need more of is Evagrius of Pontus (AD 345–399). Evagrius and the tradition associated with him are frequently cast as abstract, ethereal, and imageless. But the story I want to tell of this great early Christian desert master differs from most. The story I want to tell is woven into the material culture of the city he knew, the crags and deserts he dwelled in, and the way his followers painted his teachings. I’ll be looking for fresh ways of visualizing the Evagrian tradition and its indispensable spiritual counsel. The technology of the smartphone is arguably the greatest single visual challenge the church has faced yet. We therefore require not only the counsel of this desert master but fresh ways of seeing that counsel as well.

Why Evagrius?

The reason I urge us to attend to Evagrius is simple enough: Sick people generally consult doctors, and if the church is ill (when has it not been?), we would do well to consult the original classifier of Christian ailments. Evagrius was the first to categorize the eight deadly thoughts, which over time became the seven deadly sins. Because one of his surviving lists of spiritual pitfalls totals to nine, for some this connects Evagrius to the mysterious origins of the Enneagram. But most importantly, Evagrius caught sins before they hatched into action. In short, while many critics of the church and her would-be reformers identify the symptoms (inattention to the poor, heresies, misogyny or misandry, racism, moral laxity, works righteousness, interminable chattiness, etc.), Evagrius identifies the underlying disease: our thoughts.

Evagrius, moreover, is so practical that one of his treatises is simply titled Praktikos. Evagrius’s attention to functions of the brain has led some to call him the “father of cognitive psychology.” His extensive use of Scripture to combat negative thought patterns shares a deep kinship with the more recent emergence of cognitive behavioral therapy. Evagrius has been celebrated for demonstrating Christianity’s potential to match the practical wisdom of Buddhism, but as a great defender of Nicene doctrine, he accomplished this from within Christianity. Evagrius is best known as a father of sorts to the practice of Christian asceticism, but don’t let that word dissuade you. The word “ascesis” simply means training—that is, the practical rigours and discipline of Christian spiritual habit, habit fuelled entirely by grace. Instead of lamenting our spiritual turpitude or wasting energy blaming other Christians for the church’s failures, Evagrius wants to get you (not them) to the gym. We might therefore think of him as our personal spiritual trainer.

Instead of lamenting our spiritual turpitude or wasting energy blaming other Christians for the church’s failures, Evagrius wants to get you (not them) to the gym.

Evagrius’s speculations, including his (presumed) remarks about the pre-existence of souls and his claims about universal redemption, resulted in his censure in 553 by Emperor Justinian at the Fifth Ecumenical Council. But one scholar suggests that a more pressing reason for Evagrius’s censure may have been that his immediate and accessible approach to spiritual reality “conflict[ed] with the ambition of the emperor to achieve the same mode of authority on a far larger [i.e., political] scale.” Perhaps it is no coincidence that the same year of Evagrius’s condemnation, only a few months after the council that decried him, an earthquake caused the first cracks in one of the semi-domes of Justinian’s great church, Hagia Sophia, which ultimately led to the dome’s collapse.

But just as the dome of Hagia Sophia was eventually reconstructed, Evagrius’s reputation was restored as well. Although his speculative teachings in Greek were destroyed, they survived in Syriac translations or under the cover of more trusted authors. His more practical instructions, however, were widely copied and admired in both the Greek East and the Latin West. Still, Evagrius has only been fully lifted from obscurity by scholarly efforts in the past fifty years. The recovery of this buried tradition has all the secretive allure of The Da Vinci Code, with the added benefit that Evagrius’s story of recovery is actually helpful and true.

Evagrius was certainly not a “Gnostic” in the way that accusation is so casually hurled. He constantly counsels meditation on the good physical creation. As one scholar puts it, Evagrius “regarded prayer as transforming all of creation into a ‘cosmic church.’” “None of the mortal bodies,” Evagrius maintains, “should be declared to be evil.” Another of his defenders insists his trinitarian orthodoxy is “perfectly compatible with the Christology that is found in his Kephalaia Gnostika [his most suspect text] and his Letter to Melania.” And if Evagrius’s views on the final restoration are unclear, he did not have a chance to clarify his positions. In sum, Evagrius has been lifted from obscurity just when we need him the most. The real delight of studying him, however, comes not only from his teaching but also from his life. Perhaps one of the reasons Evagrius was so good at classifying destructive mental habits is that he had succumbed to so many himself.

A Brief Biography

Evagrius grew up in the Pontus region of present-day Turkey, near the Black Sea, and obtained an impressive liberal arts education. He came under the influence of some of the greatest minds the Christian tradition has produced—namely, the principal formulators of the Nicene Creed as we know it today. These were Gregory of Nazianzus, “the Theologian” (330–390), Basil of Caesarea (331–379), and Basil’s brother Gregory of Nyssa (334–394), collectively known as the Cappadocian fathers. These three were classmates in the great School of Athens, founded by Plato, before it was shut down by Justinian. Among their influences was someone of far more importance (according to their own testimony): Gregory of Nyssa’s elder sister Macrina.

This community would become the nucleus of monastic life in the East. The jostled terrain of Cappadocia, with its jutting crags that resemble drip sandcastles and secret monastic hideouts within, might have become Evagrius’s permanent schoolhouse of spirituality had he then become a monk. But he was drawn to the bustle of Constantinople instead, where his talents were required. There he joined Gregory of Nazianzus in the turmoil of ecclesial politics. His biographer tells us that he was “loved by everyone and held in honor by all.” Evagrius’s intelligence made him a particularly effective “destroyer of the twaddle of the heretics” (among whom he would later be named).

Life in the big city, however, seems to have dulled Evagrius’s taste for monastic meditation and quiet. He came to prefer pomp instead, including special attention to his appearance and the ministrations of servants. Evagrius became something of a clothes horse, changing outfits twice a day. He was also drawn to a Constantinopolitan woman of distinction. Which is to say, he fell in love and was thrown into emotional turmoil. It is hard to determine from the sources, but the relationship may have constituted an affair. Evagrius dreamt that he had been accused of a crime he had not committed, and to escape he was required to take a vow to leave the imperial city, swearing an oath to “watch after his soul.” Upon waking he was smitten with guilt, and almost immediately thereafter he set sail for Jerusalem—but not before taking a day to gather his beloved clothes!

On arriving in the Holy Land, Evagrius was welcomed by Melania, an aristocratic woman who had herself become an ascetic on the Mount of Olives, ministering to Christian pilgrims. She, Evagrius, and Rufinus, the founder of a nearby monastery, forged a powerful friendship based on their mutual love of the great Christian teacher of Alexandria, Origen. The rich intellectual community Evagrius had once known, sustained by the Cappadocian fathers and Macrina, had been given to him again. Still, even in Jerusalem, Evagrius concluded he was not fulfilling his vow, and he pressed on—encouraged by Melania—to the desert of Egypt itself.

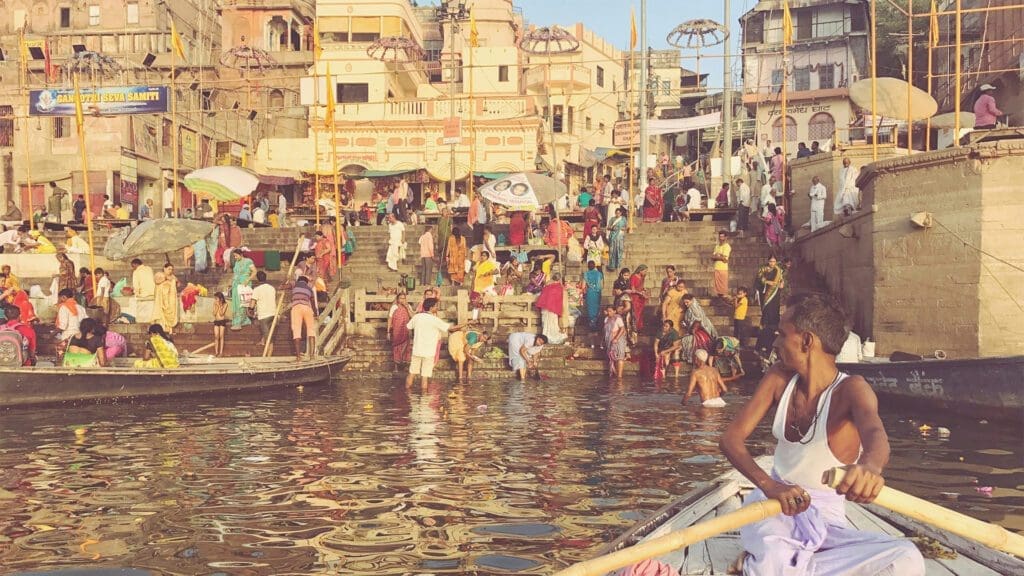

From his monastic post of Nitria in the Egyptian desert, due south of Origen’s Alexandria, Evagrius eventually emerged as the point guard of a troupe of spiritual athletes. As the Reformed philosopher Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung puts it, “We can think of Evagrius’s community as a seasoned group of spiritual directors and counselors of the Christian life. After decades of gleaning and dispensing pastoral care, they had likely seen it all.” In time Evagrius graduated from this community life to become an anchorite (a solitary monk) in a place known as the Cells. Here the refinement of Evagrius’s city training was not honoured but rebuffed. “Indeed, I have read many books and I cannot accept instruction of this kind,” he admitted in conversation with a monk named Macarius. The Coptic African monks, wary of this city slicker, announced their disapproval: “Abba, we know that if you were living in your country, you would probably be a bishop and a great leader; but at present you sit here as a stranger.” As one scholar quips, “While Evagrius accepted Egypt, Egypt did not accept Evagrius.”

Still, Evagrius received such humiliations cheerfully. That is what he had come for. He matured into a person of peace and inner power, earning the reputation as “that man of understanding.” Simply put, Evagrius, though never considering himself holy, seems to have attained apatheia, a state of deep peace and calm. Jacob Needleman, in his classic book Lost Christianity, captures the essence of the word beautifully, arguing that apatheia “is as far from the meaning of our English word [apathy] as diamonds are from broken glass.” Today we might call what Evagrius reached inner freedom. “Now this apatheia,” wrote Evagrius, “has a child called agape who keeps the door to deep knowledge of the created universe.” Agape and apatheia vitalized each other, offering the “positive and negative poles of a single unified field of force.” If the ascetic life can be related to swimming, apatheia is the graceful floating, and agape is the arm and leg strokes through the water: both are required to move. To criticize Evagrius for failing to emphasize grace would be like criticizing a swim coach for failing to constantly emphasize how water keeps swimmers afloat in the pool: it is the premise on which all the counsel depends.

Material Evagrius

A cursory read through Evagrius’s classic text Chapters on Prayer appears to show Evagrius opposed to images in any form. “When you are praying,” he insists, “do not fancy the Divinity like some image formed within yourself. Avoid also allowing your spirit to be impressed with the seal of some particular shape, but rather, free from all matter, draw near to the immaterial Being and you will attain to understanding.” Statements like this remind us that suspicion of images is not just a Protestant penchant but a mystical necessity, a universal Christian inheritance from Judaism that no Christian tradition can do without. Even so, it happens that some visual art from Evagrius’s dwellings survives.

To criticize Evagrius for failing to emphasize grace would be like criticizing a swim coach for failing to constantly emphasize how water keeps swimmers afloat in the pool: it is the premise on which all the counsel depends.

Archaeological discoveries at the Cells, admittedly dating to sometime after Evagrius, show considerable evidence for a “ritual-centered visuality.” These monks beautified their cells with crosses, and one painting even shows a cross with an image of Christ. Some of these are at the Louvre, providing something of a mystical Christian foundation for that great collection of art. Elizabeth Bolman cannot help concluding her study of the visual culture of the Cells by citing Evagrius, who writes, “By true prayer a monk becomes another angel, for he ardently longs to see the face of the Father in heaven.” Evagrius was more visual than we thought.

Similarly, one scholar exonerates Evagrius of “isochristic” accusations (the claim that the mind of Christ is the same as any other mind) by elucidating Evagrius’s rich theology of the iconic nature of the mind, which is completed only with the icon of God’s face—namely, Christ. It is no small thing that the church father once understood as the apostle of imagelessness can now be considered an iconic thinker par excellence. Even John Cassian, Evagrius’s champion in the Latin world, has been shown to have advocated contemplation as “imageless, but not visionless; in prayer, one should seek the vision of Christ in his divinity, which is precisely the vision of the consubstantial Trinity.” But if Evagrius and Cassian permitted the mental vision of Christ without advising physical images, it would not be long before their monastic followers unfurled the entire Evagrian method of prayer in beautiful wall paintings as well.

Catching Demons in the Act

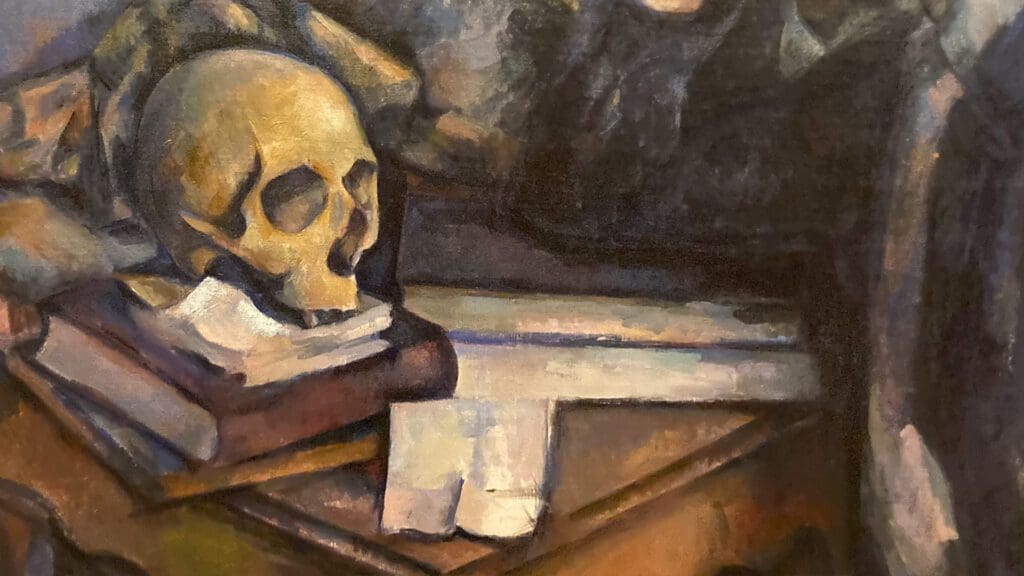

They did this because the more one thinks about it—or, better, the more once practices it—the more Evagrius’s method becomes exceedingly visual. Negative thought patterns must first be seen. Evagrius expressly says, “The demonic thought is an imperfect icon . . . fabricated in one’s thinking.” We need not choose between literal demons—actual fallen angels—and the demonic conceived as destructive thought patterns. Reality is complex enough for Evagrius—and for the most thoughtful Christians today—to require both registers. The more pressing point is that to have a fighting chance against our thoughts and our passions, we have to catch them in the act. As Evagrius counsels, “We must take care to recognize the different types of demons, and take note of the circumstances of their coming.” And elsewhere: “If there are any among you who wish . . . to gain experience in this contemplative craft, keep careful watch over your thoughts.”

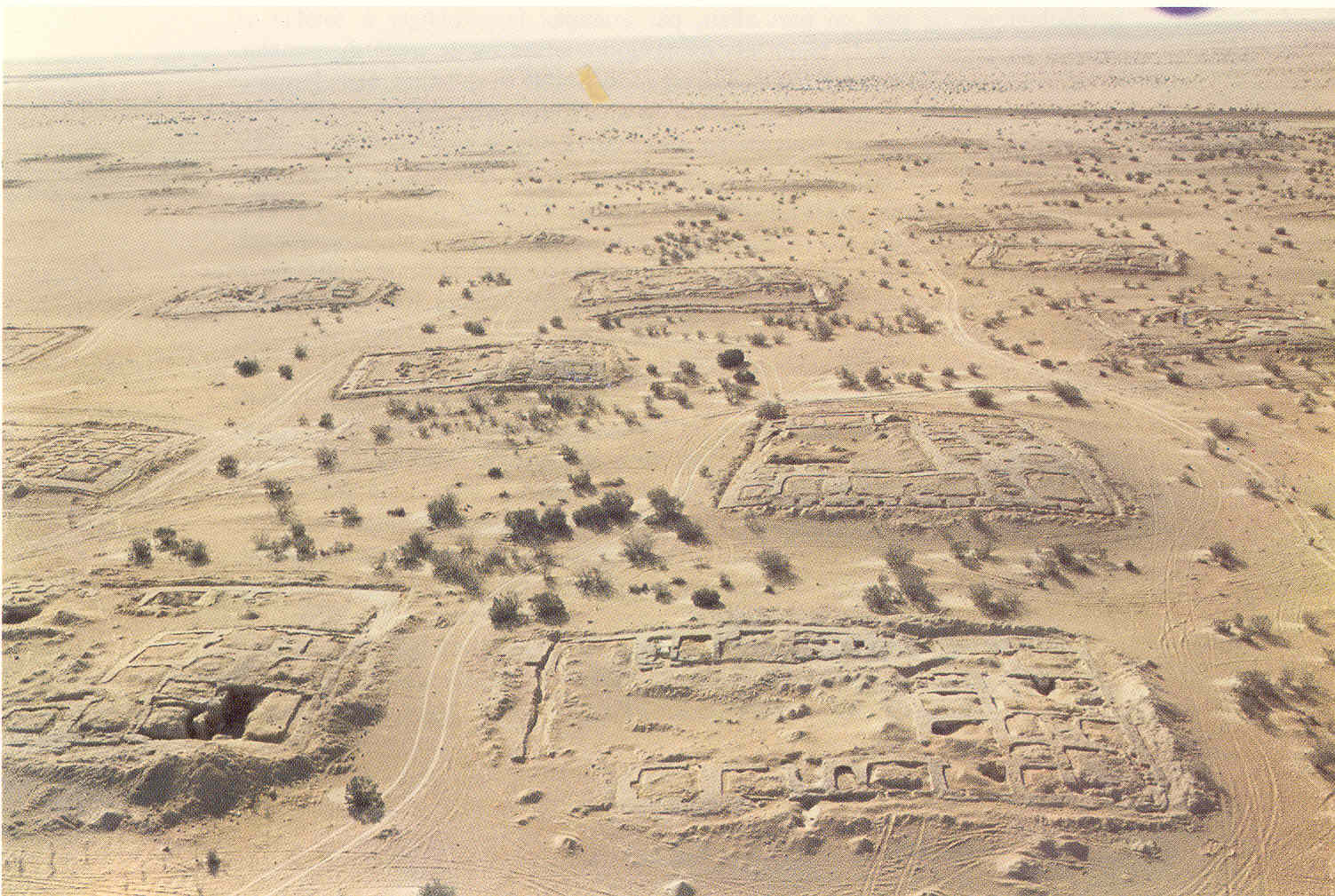

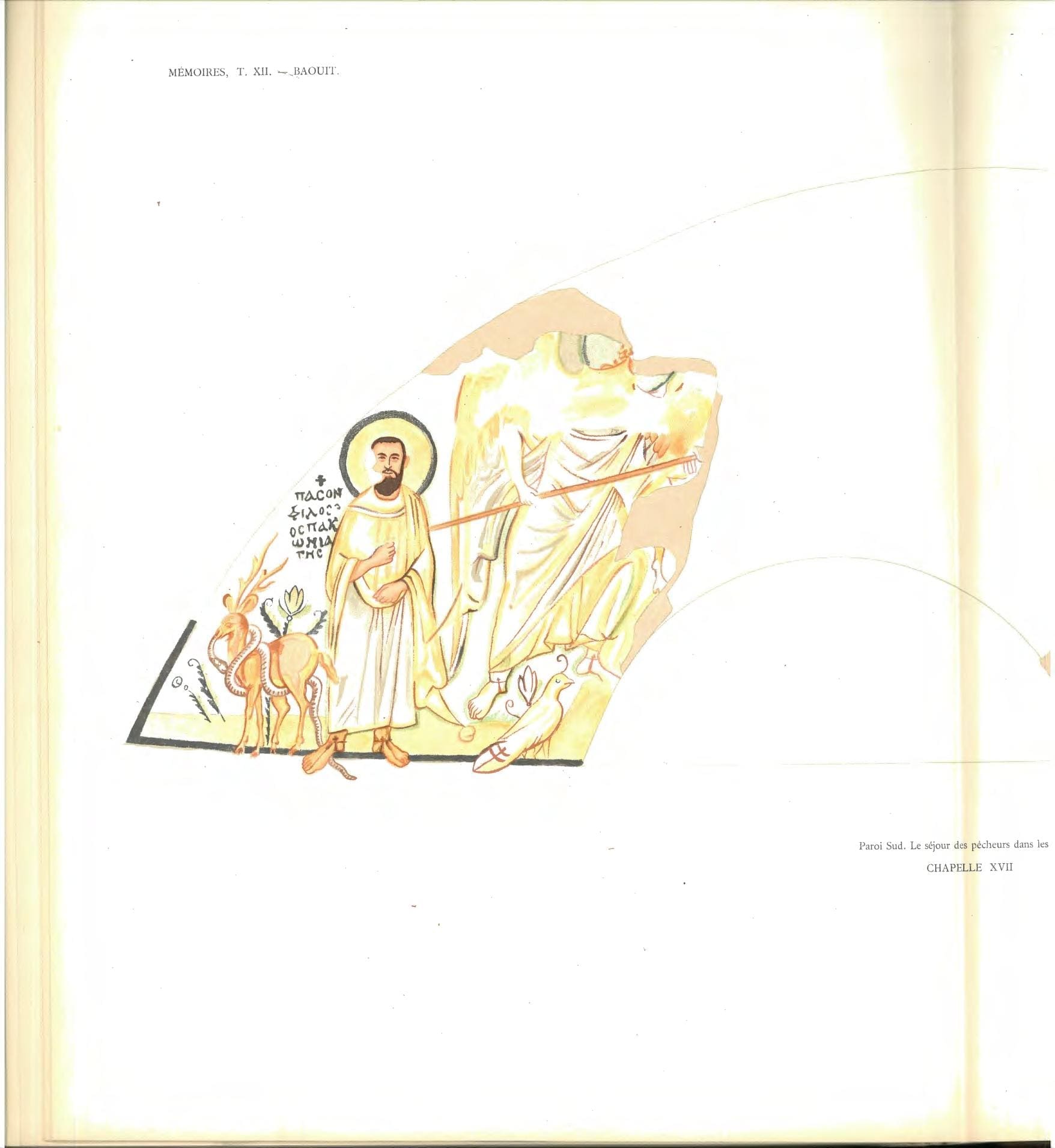

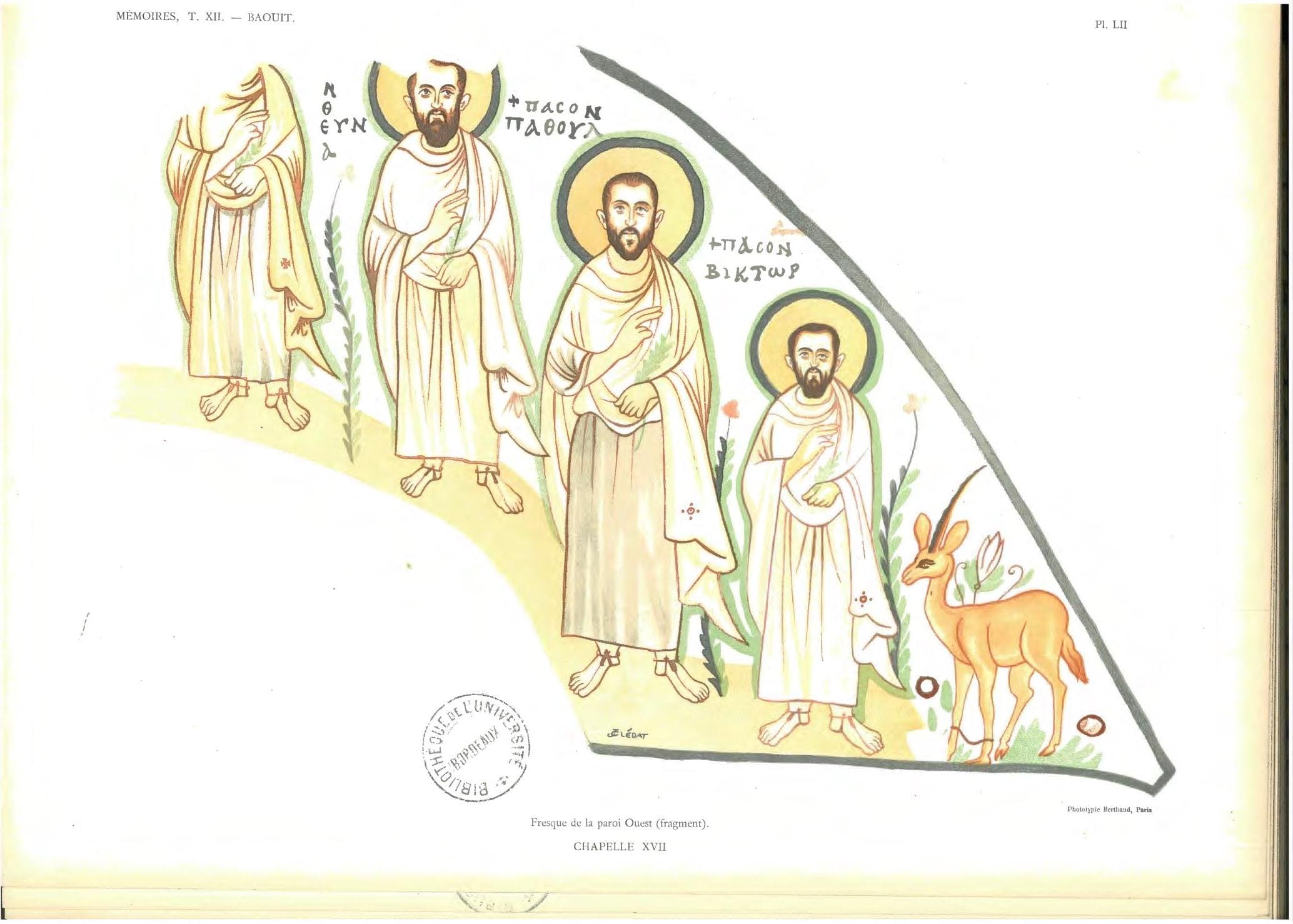

For Evagrius, the danger of the difficult-to-translate demonic entity acedia, for example, “is precisely the fact that it conceals itself from the one who experiences it.” And for Jean-Charles Nault, one of the reasons acedia has done so much damage to the church—he calls it “perhaps the root cause of the greatest crisis in the Church today”—is that it is out of view, no longer seen. As Evagrius puts it, “We ought to consider which of the demons [thoughts] are less frequent in their assaults, which are the more vexatious, which are the ones which yield the field more readily and which are the more resistant.” No wonder, then, at Egyptian monasteries not long after Evagrius, images survive of monks visualizing the temptations that besought them. Take the image below from the Monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit, which was founded when Evagrius was still alive; even if the paintings came a few centuries later, they reflect his thought remarkably well. One scholar suggests the deer is the monk, and the serpent is the thought, whether lust or envy or anger, which has the monk in its grip.

How exactly do these demons entangle us? Like hellish matchmakers, they cleverly combine afflictive thoughts with our obsessive underlying desires, what Evagrius would call pathos. For example, a pathos for acclaim and attention will be agitated by the thought (logismos) of vainglory, which Evagrius names the “pleasure of thinking about being honored by others.” Vainglory’s victims are in turn thrust into pride if they get the acclaim they want, or plunged into sadness if they don’t. These conditions are perfect for advancing the careers of Christian college professors like me, or for generating massive social media platforms, but not so much for deepening spiritual life. Advanced degrees cannot thwart these demons and might actually help them along. Martin Laird explains the demonic strategy exposed by Evagrius using a Velcro analogy:

But by seeing the thought of vainglory and releasing it, I short-circuit the process. If, then, by God’s grace I can manage (sometimes with tumultuous struggle) to regularly still myself, I can enter an inner spaciousness—that is, the “decidedly non-stoic” apatheia that generates agape. The same series of paintings shows the monk—in the form of a blissfully snakeless deer—having overcome this particular thought.

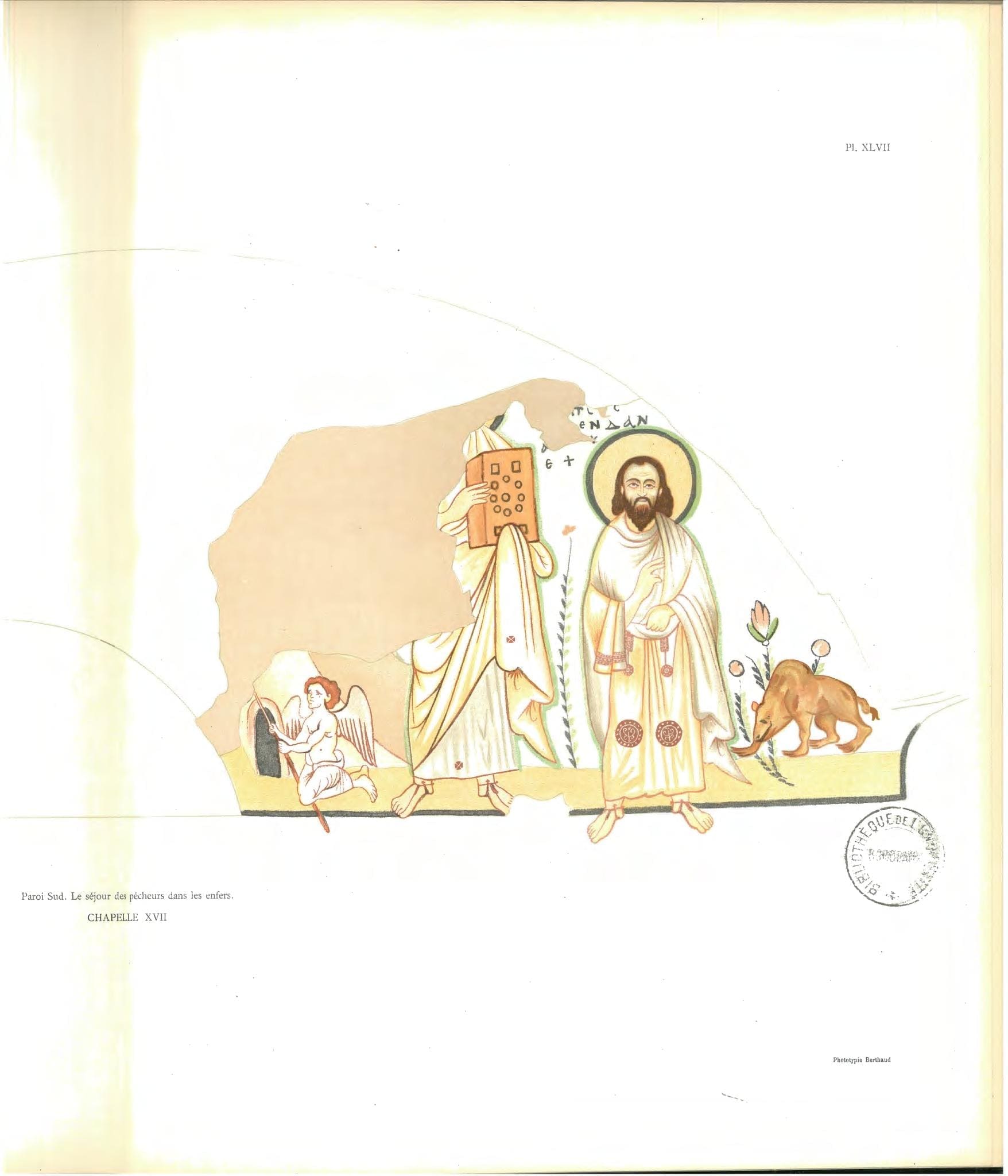

In another instance, the monks at Apa Apollo at Bawit visualized the deadly thought itself as a bear that longs to devour its monastic victim. But the bear in the painting below—whether we understand it to represent lust, anger, or despair—is looking especially downcast because it is no longer being actively engaged. It can no longer hook the passions with thought and thereby generate an accompanying “video.” The serene monk beside the bear has taken Evagrian monastic counsel to heart. As Abba Poemen so confidently declared, “I will pierce the lion and I will slay the bear” (cf. 1 Samuel 17:35).

Evagrius counsels us therefore to summon all our strength not to attack the world, still less our fellow Christians, but to set our sights on destructive thought patterns instead: gluttony, lust, greed, anger, sadness (a.k.a. envy), listlessness, vainglory, and pride. That crusade you may have been planning against “Christian nationalism” or “critical race theory” is a red herring. That book project that will sort us all out might not be the solution either, because better thinking is not necessarily the solution. Evagrius is especially important because while he could think with the best of them, he also taught us how not to think. For those of us who have long been taught the importance of the Christian liberal arts, especially “critical thinking,” this can come as something of a surprise. Evagrius even defines prayer as “the letting go of thoughts.”

That crusade you may have been planning against “Christian nationalism” or “critical race theory” is a red herring. That book project that will sort us all out might not be the solution either.

For some Christians this can be terrifying. The Trappist monk M. Basil Pennington, after years of teaching this form of prayer to laypeople, was repeatedly faced with the question as to whether surrendering thought, and the passive state that comes with it, will open us up the demonic. He loved to hear that question, because as a seasoned contemplative in the tradition of Evagrius, he had a great answer to it.

Two things surprise me about this statement: first, that despite the importance, even urgency, of this Evagrian method of prayer, it took so many years for at least this American Christian to discover it; and second, that when pursuing these depths of Christian contemplation, the material culture of Christianity—its icons, buildings, and wall paintings—might actually help.

For when Evagrius’s style of mysticism is realized, the world does not disappear as in some other forms of spirituality. On the contrary, the material world—which is pervaded by the Godhead while never containing it—can finally become itself. It seems to me that a truly Evagrian spirituality is therefore not complete until it reckons with the physical, the visual, the artistic, the material.

I hope to pursue this further in the columns to come.