In the eleventh century, nearly 150 years before the Florentines built the cathedral the city is known for, they built a mosaic-lined baptistery outside the old church. Only baptized Christians were allowed inside; catechumens listened to preaching in courtyards outside. When Lorenzo Ghiberti designed his famous Gates of Paradise reliefs in 1452, they were so named because the newly baptized, dressed in the white robes of the redeemed, would walk in joyous procession through those gates into the courtyard, called the Paradiso, between the baptistery and sanctuary, and then into the church.

That was then. This is now. Not only is baptism no longer required to enter the Duomo, but also in the twenty-first-century West, we have lost that architectural memory and the theology and visual vocabulary that built it. Lisa J. DeBoer’s book, reflecting a new trend, is an effort to recover that vocabulary. Many evangelical churches still dismiss the importance of architecture and artworks, but a recent study may change their minds. Commissioned by the Christian youth organization Hope Revolution Partnership in the United Kingdom, the study shows not only that 21 percent of young people in Britain between the ages of eleven and eighteen describe themselves as practicing Christians but also that 13 percent say that visiting a church or a cathedral was one of their top three reasons for becoming a Christian. An important part of our witness to the gospel might be architectural. In that case, we might read DeBoer’s book as a missional opportunity in our secularized world.

A Brief History of Reform and Rebuilding

DeBoer launches her account of the role of the arts in worship with the group that has lost the least of its historic memory— the Orthodox Church. Here she focuses on two important facts. First, for the Orthodox, to enter the church is to enter the new Jerusalem, the city of their true citizenship, as Augustine put it and the Florentines understood. Every part of the setting and worship is rooted in that understanding. Second, the Orthodox have a long-standing covenant with icons, images of the Savior, the Virgin Mary, and the saints. Icons are what art historian Alexei Lidov calls “mediating images,” through which the saints across time are present, just as they are in the Heavenly City. Worship is experiencing that reality.

The Roman Catholic understanding of the role of the arts is tied up with its first thousand years of unity with the Orthodox East. Many Catholic churches had and still have cherished icons. When the Eastern Byzantine Empire twice condemned icons in the eighth and ninth centuries, Rome never went along. In each case, iconoclasm was overturned by the arguments of monks, first John of Damascus and then Theodore Studite. John, who was writing from a city controlled by thoroughly iconoclastic Muslims, argued that because Christ took on a face and a body, Christians could and should make images not only of him but also of his mother and the saints. His argument for icons grows from the incarnation.

Five hundred years after the split of East and West in 1054, Martin Luther launched the Protestant Reformation, which again split the Western church. One of the issues that compelled Luther was that images— justified on the rightful basis of incarnation— had become idols in the hearts of many faithful. The combination of this alongside the hierarchy’s trading indulgences to get out of purgatory for the money to build St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome placed art and architecture back into hot debate within the church. The response was not just a development of a new stream of Protestant approach to the arts, but a reformed Catholic Church. The Council of Trent, 1545–1563, responded with many reforms, among them specific instructions for what kind of art was acceptable in the church and how it was to be used. Art, particularly painting, was to focus on Christ’s entering into daily life and on believers’ experiencing new life in him. The works of Caravaggio and Guido Reni are prime examples. Think of Caravaggio’s work in St. Agostino in Rome, where the Virgin holding Jesus is in the doorway and a beggar with bare, dirty feet is kneeling to see the Christ child. Or, The Calling of St. Matthew, where the apostle is called from sitting at a table counting money in what looks very much like a Renaissance bar.

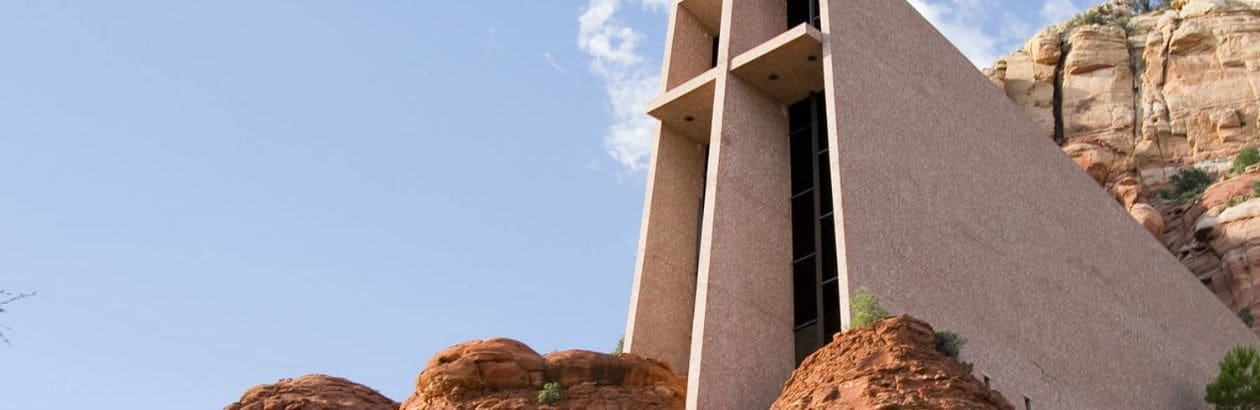

After 1945 the postwar generation of Catholics looked in large part to the art world around them both to rebuild after the devastation of World War II and to inspire new churches for a new age. In Europe there are the Eglise Notre Dame de Toute Grace at Plateau D’Assy (1937– 1946), designed by Maurice Novarina, with works by such artists as Rouault, Braque, Bonnard, Chagall, Leger, Lipchitz, and more, and the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, where Matisse designed the interior, the stained glass, and the vestments. In Rome there are multiple examples of 1950s modern churches ringing the historic city centre. In the United States, we have the Chapel of the Holy Cross (1956), designed by Anshen and Allen as a Catholic church in Sedona, Arizona, and the Parish of St. Frances de Sales in Muskegon, Michigan, by Marcel Breuer.

Cross-pressured Congregations

While some evangelicals turn to historic examples of the role of the arts in worship as do the Orthodox and Catholics, DeBoer argues that most draw inspiration from the contemporary art world or from popular culture. But in many cases, this places them in competition with museums as places people go to worship and experience the divine. For many Westerners, especially in the United States, art museums have replaced churches and synagogues as places of worship.

As architect David Gruesel notes, wealthy New Yorkers such as John D. Rockefeller Jr. displayed their wealth by building churches such as the neo-Gothic Riverside Church in New York or the chapel at the University of Chicago. No more. Today their counterparts build art museums. By mid-century the shift was in full swing and has only picked up speed in the new millennium. At the fiftieth gala anniversary of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 2015, one of the patrons interviewed for a film tribute said: “We don’t go to church—we go to LACMA!”

This development, of course, puts pressure on congregations in two ways. First, the West is now drenched in art and images— be it popular culture from television, social media, computer games, advertising, or the ever-growing number of art museums and cultural centres. How can a congregation ignore that and connect to the daily experience of its members? Second, as I’ve said, evangelical congregations in particular have no background from which to draw a theology of images and their place in worship. For some that means simply dismissal and withdrawal, if not condemnation, of the arts tout court. For others that means embracing art in some way but with little or no knowledge or understanding of the art world, let alone the history of images in the church.

DeBoer traces the effect of this situation through the arts practices of six congregations around Grand Rapids, Michigan. Two come from the historic Protestant mainline, two from the Reformed tradition, one Covenant church, and one post-seeker congregation started within the last thirty years. The role of the arts in these congregations varies. They sponsor concerts and art shows, provide summer camps and after-school programs and classes in the arts. incorporate the arts in the design of their worship spaces, create exhibitions to enhance their sermons, and use digital media in worship and in representing their congregations online. While her descriptive work here is helpful, analysis of the purpose and effects of these practices provides some enterprising scholars an opportunity for further work.

The Important Questions

In part 2 of her book, titled “Discernment,” DeBoer analyzes how each tradition approaches ecclesiology and the Western art system through the lens of its own history and theology. She asks how the arts “express a congregation’s theology of itself as a church.” Do they see themselves primarily as part of the universal church or as a local body? Does their worship focus more on communal or individual expression? How do the arts express the congregation’s understanding of its place in the story of salvation as well as its experience of the presence of God in their lives?

The Orthodox and Catholics in DeBoer’s analysis emphasize the universal nature of the church expressed in communal worship. Private devotion is valuable but secondary. For the Orthodox, the distinction is less sharp because most have home icon corners where they pray with the saints. In each case the arts both reflect and enhance theology. Protestants, too, celebrate the universal church, but for them individual experience has always “superseded corporate identity.” The focus is local—seeing the Word, faith, and witness working in the immediate community. The arts must support the individual in his or her personal walk with God, which may be one reason few Protestants, particularly evangelicals, see a serious role for them in worship.

Certainly since the middle of the twentieth century, the North American art world has taken little interest in the church. It is here that DeBoer raises questions few churches have faced. For example, do artists serve the institution of the church, or do they adhere first and foremost to the professional standards of their training? Where loyalty to church teaching predominates for Catholics and Orthodox, the professional ethos of the art world exerts a much stronger pull for Protestants. Then there is the question of naturalistic and abstract art styles in art works made for churches. This one has a long history in both Catholic and Orthodox experience, often fraught. Vatican II favoured the abstract as more spiritual; Orthodox icons incorporate both.

DeBoer’s final question is the most important: inculturation versus enculturation. Does the art world shape the church, or does the gospel shape the arts? The Orthodox, of course, manifest the longest experience of theologically rooted art and architecture in their worship. As pointed out earlier, for them the church building is what Lidov describes as a three-dimensional icon of the heavenly city, a sacred space mediating between earth and heaven. There everything works together as a whole—icons, incense, music, procession, all the decoration. To separate out any one part is to miss the meaning. Catholics, too, have a long tradition of art, some of the greatest in Western history, inspiring worship and leading congregants to a deeper understanding of their faith. Perhaps in an age when church planters emphasize the need for gathering people around a hard doctrinal core with flexible edges, we need to reconsider the ancient practice of separate spaces for the seeker and a sanctuary with ceremonial induction for the believer. Once again, it is Protestants who face the greatest pull toward enculturation because they are more influenced by the art world than by theology when it comes to the arts in worship.

Reading DeBoer, I was impressed once again by the compelling need for all Christians, but especially Protestants, to study the theology that brought the arts into the church in the first place. For example, the idea that the church itself is a three dimensional icon of the new Jerusalem need not be limited to the Orthodox. Augustine’s City of God shaped the design of Western European cities for eight hundred years, according to urban historian Lewis Mumford. The church, the beautiful embassy of our true home, was at the center, open to everyone—rich and poor alike. Next door were almshouses for the poor, hospitals for the sick, and schools to educate the young. A marketplace was seldom far away. New Jerusalem principles informed the very structure of these cities. I have pictures from Toulouse, France, which, of all places, is a great example. Who knew?

We have to ask: How would we worship and how would we live and design our cities if we understood ourselves to be standing in the new Jerusalem surrounded by saints living and dead every time we entered the church?