E

阅读这篇文章的自动翻译。

辩证法汉语课

在压力下向教会学习。

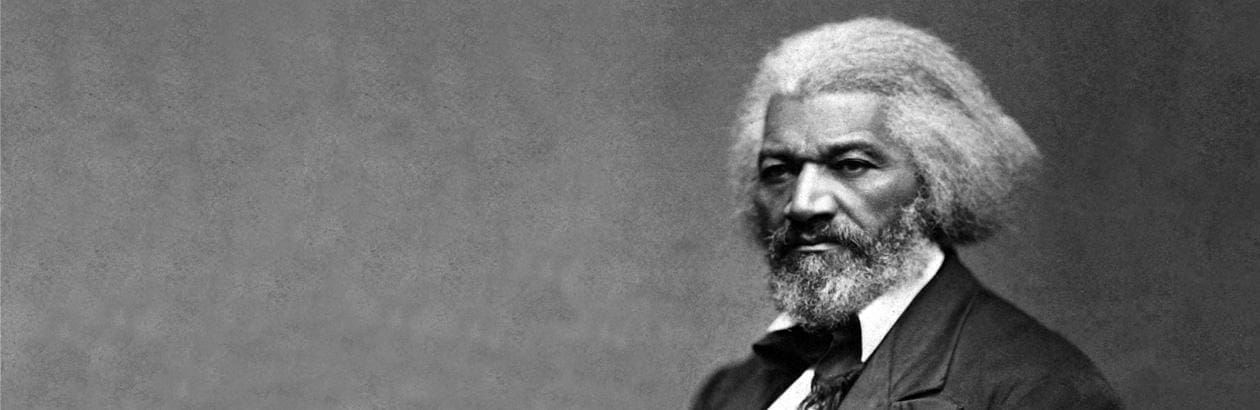

八十年前的今年,迪特里希·邦霍弗在纳粹德国被盖世太保逮捕。他最初被关押在战时监狱,后来被转移到集中营。他在战争结束前不久被处决。在世界的另一端,在邦霍弗被捕七十五年后,另一位牧师在中国西南部被捕并被判处九年徒刑,这是近几十年来对家庭教会牧师判处的最长刑期。五年来,王毅一直在自己的监狱集中营里睡觉、醒来、吃饭和挣扎,其苦难与来自前一个世纪和不同国家的兄弟一样,颠覆了一个寻求人民最终忠诚的国家。

当我意识到2023年是政治异议、宗教自由和辩证法历史上的这两个周年纪念日时,我决定重新审视邦霍弗在生命尽头提出的关于教会本质的一些问题,并考虑一位华人牧师给出的答案,他比当今西方世界任何人都能够宣称的更真实地延续自己的遗产。

基督教世界的持续解体以及传统基督教在西方文化储备的流失,使许多领导人争先恐后地想出教会的公开见证人应该是什么样子,尤其是在美国。尽管邦霍弗生活在一百年前,但他对这个难题并不陌生。他在德国的知识环境中生活和接受过教育,德国知识界预测并帮助创造了我们现在所处的世界。

当他写监狱信并面临二十世纪初极权主义背景下的最终死亡时,邦霍弗用德国哲学和神学的精华得出结论,人类已经发生了变化。男人和女人不再觉得需要上帝,也不再需要他回答他们无法回答的问题。他写道:“人类现在可以自主运作,无需提及神圣的恩典或神圣的真理。在世界成熟的时代,无论是在科学领域,还是在一般的人类事务中,甚至越来越多的宗教领域,人们都不再需要将上帝作为工作假设。”人类已经长大,Bonhoeffer 有一个问题:在成熟的世界中,教会的意义何在?

这是一个有争议的问题,来自福音派人士喜欢尊敬的烈士。许多人将邦霍弗的监狱著作描述为巨大胁迫的结果,几乎认为他认为世界已经成熟是劳改营引发的心理崩溃的结果。无论从历史学角度看待邦霍弗的心理健康及其对他著作的影响如何,据其自身的估计,在二十一世纪,世界已经成熟的观念对我来说似乎是理所当然的。

人们不必相信现实世界已经走向成熟,我们所有的科学和技术实际上已经缩小了人类需求的差距,无论是精神、情感、心理还是身体需求的差距,人类就认为这是真实的观念所驱使。自Bonhoeffer提出主张以来,世俗发展已接近一个世纪,我觉得这是对现代世界如何理解自己的恰当描述。作为对世俗世界的心理描述,邦霍弗的观察使我深信不疑。

那么,在这样的世界里,教会的意义何在?

今天,在美国福音派教会中,我们发现了在世界走向成熟时对我们的文化边缘化的各种回应。一方面,我们发现人们对基督教民族主义的兴趣和承诺令人震惊地重新抬头,这是教会的最佳姿态。另一方面,我们发现我们社会的思想领袖和文化创造者对意义和身份的定义有所屈服。在中间,我们发现一大堆混乱的尖锐声音,他们说,如果我们能更清晰地论证,提高数字化水平,更频繁地发表文章,更精明地施加影响,我们就能以某种方式扭转几十年后才发现的局面,更不用说解决问题了。

但是在这个世界的其他地方,人们给出了不同的答案。

像他的德国前任一样,王毅生活在先进的世俗背景下,寻求在不允许公共领域或公开言论的极权主义社会中为教会开拓空间。邦霍弗在二十世纪初对人类现代自给自足以及不需要教会提供答案的看法,中国人(占世界人口的近20%)作为权威的现实生活和教学。这并不是说二十世纪的德国世俗主义等同于二十一世纪的中国。但是,作为近一个世纪以来世界上最正式的无神论社会之一,中国是一个认为自己已经走向成熟的世界的重要组成部分。中国共产党(CCP)放弃了帝国邪教、民间宗教和较早的儒家思想形式,转而追求科学技术,最终追求资本,以此作为所有人类和社会问题的答案,长期以来一直教导其人民,与以往所有历史相比,中国社会已经 “成长”。自20世纪20年代以来,消灭继承的意义和宗旨一直是中共的明确目标。

但是,尽管邦霍弗得出结论,教会有义务进行调整,以见证上帝以及男女与他建立关系的方式,但王毅却试图宣布,在成熟的世界中,教会的目的是与世界对自己的理解相矛盾。他用一个精湛的芭蕾舞演员的比喻,他必须在垃圾填埋场中间的舞台上表演。表演和舞台之间的对比旨在激发观众理解改造垃圾填埋场的必要性。王毅写道:

关键是信心,信仰需要一个舞台。Faith 就像一位芭蕾舞大师在破旧的舞台上优雅地跳舞。一方面,只要舞蹈很漂亮,舞台破败又有什么关系?或者,想象一下这位舞蹈大师在宏伟的舞台上表演的那一天会多么光彩夺目。但是,就目前而言,上帝说,舞蹈的价值必须在破旧的舞台上表达。

他还说,

让我再次提醒大家,我们的政府雄心勃勃。他们的目标不仅是获得社会秩序,还要垄断垃圾填埋场和地铁站的意义。因此,当我们在垃圾填埋场跳芭蕾舞时,政府很担心。当我们在地铁里拉小提琴时,我们会发现警察把我们钉在地上。但是,这是垃圾填埋场的部分含义,因为上帝允许他们雄心勃勃,因为他想放大信仰的价值。总的来说,表演环境越糟糕,教堂节目的 “末世论意义” 就越大。

与Bonhoeffer不同,王毅和他在家庭教会的许多同龄人认为,揭示真正人性的过程必然是一个对比和对立的过程。

世界真正的时代到来并不取决于人类对自己的看法。说人类实际上可以在这个世界上成年,这让人想起了C.S. Lewis描绘的儿童时代人性,当他被邀请去海边旅行时,他满足于在街上玩泥馅饼。对于王毅及其神学运动中的人来说,在末世论到来之前,当真正的人性终于成熟,神的国度圆满完成之前,教会的存在恰恰证明了这样一个事实,即我们尚未成年,人类无论身处何时代,仍然对自己的泥馅饼感到满意。

根据包括王毅在内的许多中国家庭教会的说法,揭示人类状态的最重要的道歉时刻发生在教会愿意 “走十字架之路” 的时候。为上帝国度的真实作见证,必然涉及呼召人们与基督一起受苦。教会跳的芭蕾舞不是胜利和权力的舞蹈;它是集体苦难和牺牲的舞蹈,邦霍弗本人对这种舞蹈了如指掌,尽管可能无法理解中国家庭教会使用的术语。

王毅说,

我们如何证明我们的动机是信仰,而不是政治目标?我们必须愿意走十字架之路,为我们的信仰而受苦。。

这就是传福音和辩证法的方式。教会有机会在社会及其统治者面前抗争、坚持不懈,并为我们的信仰付出代价。如果说这是过去二十年来首次在全国范围内对家庭教会的迫害,那也是该教会在过去二十年中首次获得福音和道歉的机会。

你必须相信什么才能说当教会遇到困难时,它的苦难是最伟大的道歉和传福音的时刻?甚至比在舒适、力量和名人方面所做的努力还要大?展望本世纪的剩余时光,无论它最终是否会被证明是中国世纪,这些问题一直困扰着我。

中国家庭教会在苦难和隐秘中诞生。因此,在当代辩证法中,它并不被认为值得注意。但是我们应该重新考虑并给予应有的考虑。尽管我们经常将中国家庭教会置之不理,使其现实与我们的现实保持距离,但他们的遗产与其说是竹林中的奇迹,不如说是让人想起邦霍弗的遗产:面对国有化势力,对普世教会的顽固承诺,不愿效忠声称代表世界走向成熟的大国。

与常见的误解相反,当中国共产党于1949年上台时,它并没有废除宗教活动。相反,它只要求所有宗教表现出对新政府的爱国支持,并接受政府当局的监督和监管。最终,这项努力在一座名为三自爱国运动(TSMP)的州教会中得到了巩固。除了文化大革命最激烈的几十年外,中共从未试图阻止宗教活动在中国的存在;它只是要求基督徒服从其权威。该党希望得到人民的爱与忠诚。

你可以同时爱上帝和国家,对吧?在20世纪50年代初,中国大约有一半的基督徒认为,是的,这是可能的。在西方和日本帝国军队席卷中国一个世纪之后,基督徒被共产党恢复国家主权的能力所驱使。成千上万的中国基督徒签署了一份名为《基督教宣言》的文件,承诺他们热爱中国,效忠政府。

但是中国另一半的基督徒说不。长期以来以拒绝对中国新成立的本土教会的传教监督而闻名的王明道等人物坚持认为,只有基督才是教会的领袖。国家不可能对教会的内心生活拥有任何权力,第一代家庭教会牧师为了维持教会的这种定义而选择了失去政治保护和权利。这就是我们现在所说的中国 “家庭教会”。家庭教会不是根据他们在哪里聚会或如何聚会来定义的;他们的定义是他们不愿进入国家教会。

在20世纪80年代中国重新开始开放之后,它似乎越来越倾向于不受宗教管制。从20世纪90年代到21世纪初再到2010年代,随着基督教在中国城市中心的蓬勃发展,人们对家庭教会的容忍度越来越高,尤其是在中国沿海最富有、最稳定的城市。“家庭教会” 一词实际上不能局限于在家中秘密举行的教会会议。毕竟,由五百人组成的会众在周日早上在租用的商业空间里聚会,他们自称为家庭教会(嘉亭教会)或 “家庭教会”。它们在很大程度上仍然是非法的,但如果不破坏和平,它们或多或少会被容忍。

2018年,当中共实施一套新的宗教法规时,情况发生了变化。重点一直是将所有宗教集会限制在TSPM范围内,在中国,对家庭教会以及许多其他形式的宗教表达的骚扰和迫害明显增加。2018年12月,王毅被捕,他的教会——早雨圣约教会成员遭到暴力袭击,这是当年习近平领导下迫害将加剧的几个信号之一。在Covid-19大流行期间,当习近平对家庭教会严厉使用Covid-Zero政策时,情况更是如此。尽管目前的情况与二十世纪的迫害相去甚远,但这通常被认为是自中国家庭教会成立之初以来最严厉的镇压。

我的一个朋友是中国一个主要城市的中国教会种植者。在Covid-19爆发几周后,也就是武汉封锁之后,他的小教堂就成立了。短短一年后,他们的教会已从十几人发展到一百人,在他们的第一次洗礼星期天,他们为六名成人和九名儿童施洗。现在,在他们成立的第二年,他们已经在着手建造一座全新的教堂。这是在完全服从政府的压迫性Covid Zero政策,以及生活在世界上城市化、数字化、世俗化和竞争最激烈的城市之一所面临的所有更为平凡的压力的背景下发生的。他们作为教会所面临的压力超过了我们在北美所经历的任何压力。

《世界基督教百科全书》指出,在1970年,中国自称是基督徒的人不到一百万,占人口的0.1%。它今天列出的数字为1.12亿,几乎占人口的8%。即使考虑到二十世纪末中国人口的大幅增长,这也是中国自称基督徒的六十倍增长。自中国家庭教会诞生以来,它一直在发展——没有政治保护、公共平台或公认的机构。如果我们想为预计的二十一世纪西方教会将面临的压力学会道歉,我们就应该考虑一个在七十五年的压迫下不仅幸存下来而且呈指数级增长的教会可以教给我们什么。

在中国建立立足点时,中共宣布现代中国社会是已经成熟世界的一部分。为了否认对现实的这种描述,家庭教会已经遭受了七十年的苦难。

他们告诉我们,教会的公共生活必须是十字形的。上帝的恩典使教会与基督团结在一起,在这种结合中,教会必然参与基督的苦难。我认识的一位家庭教会领袖指着马太福音 10:24 来解释。她提醒我们,仆人不能凌驾于主人之上,学生也不凌驾于老师之上;因此,如果我们的主人和老师在这个世界上的生活以苦难为标志,那么教会也应该预见到同样的情况。

王毅用以下方式描述了教会公开见证的十字形性质:

因为罪,现在的世界是上帝创造的世界的颠覆。十字架使这个世界向后翻转。福音具有强烈的末世论性质。福音不是关于今生如何改变的好消息。尽管今生是其中的一部分,但福音的重点延伸到了永生。在这个被罪颠倒的当今生活中,永生的好消息是通过反向手段——耶稣拯救我们的手段来表现出来。十字架是我们所相信的,也是我们信仰的手段。十字架不仅是内容,也是形式,这种形式告诉我们世界尚未完成——上帝的创造尚未完成。当我80岁时离开这个世界时,我的生活也并不完整。

那我该如何表现一个看不见的世界呢?我如何展示我今生的真正财富?我通过贫困来证明这一点。我如何显示复活力?经历痛苦。我有受苦的能力。我可以付出,因为我有。我给的东西证明了我所拥有的一切。。

因此,基督徒通过十字架的颠覆手段在这个世界上为基督作证。我的生活、上帝的创造以及整个世界历史都未完成。十字架意味着你对未来抱有希望,而不是在当下实现希望。

在这份声明中,王毅为教会呼吁与基督一起受苦提供了宇宙的、末世论的维度。走十字架的意愿和意愿是教会公开见证的必要特征。他甚至争辩说,如果教会缺乏被认识和认同痛苦的意愿,他就无法参与基督的生活,也否认他的领主地位。

王毅想起邦霍弗关于 “廉价的恩典” 和诱惑许多基督徒的宗教安慰的警告的某些方面,他认为,走十字架之路对于教会使命的纯洁性是必要的。当你听到人们谈论他们对教会被边缘化的担忧时,你最常听到他们讨论的是什么?当然,我们面临着各种各样的问题,其中许多问题集中在圣经人类学(人类性行为、堕胎、安乐死等)和良心权问题上。但是,许多人一直担心教会的免税地位和财产权。许多人很快将有形资产与教会的自由联系起来。

王毅认为教会应该战斗,但他不相信要为许多美国人渴望保护的事物而战。

教会必须愿意为死而战,不是为了看得见的公民权利和法律地位,而是为了天国的钥匙和看不见的福音的力量。教会永远不应该放弃她最重要的资产。它们不是教堂财产或金融存款,而是上帝赐给我们的东西—— “奥秘”,即我们的主赋予我们的神圣教义、神圣职务和圣餐。

王毅在这里并不是说基督徒没有被要求为更好的制度和政治保护而努力;他只是争辩说,教会应该非常清楚上帝赋予教会在紧急情况下保护什么。尽管某些权利可以被准确地理解为一个理解和重视宗教,特别是基督教会的作用的社会的产物,但它们并不是教会的定义。王毅认为,当有人反对时,教会应该愿意放弃他们的公民权利、法律地位、物质财产和金钱。但是,教会决不能放弃的是其教义、圣餐和教会的办公室。

有多种方法可以为教会提供政治保护,包括宪政民主,但王毅坚持认为,基督教民族主义不是解决方案。此外,我能想到的每一个 “基督教国家” 的历史例子本身都是在某个时候以某种方式迫害教会的。如果我们不是基督教民族主义者,那么我们必须以一种使我们的教会做好准备来计算上帝实际要求我们保护的代价,而不是我们可能认为教会成功所必需的许多保护措施。

在困难时期,教会必须愿意放弃其公民权利,以维护其使命的纯洁性。为了让公众见证,教会必须为真正的定义而战。王毅提醒我们,免税和教堂建筑不是教堂。为了证明其真实本质,教会必须像主人耶稣一样愿意放弃其所有权利。我怀疑,一些美国教会害怕失去的所有东西都是邦霍弗所指的隐藏廉价恩典背后的装饰。王毅指出,为了提炼和净化我们的忠诚和爱心,并确保教会理解门徒训练的代价高昂,必须留下一些东西。

王毅认为,十字架之路是证明福音真理的必要条件。如前所述,十字架之路就是辩证法。教会受到的迫害越多,它就越能向世界证明基督的王权。根据王毅的说法,这就是教会在胁迫下成长的原因。王毅在被捕前几个月的主要希望是他能够在自己的审判中发言并公开宣布自己的信仰。他想在法庭上向法官、律师和官员宣讲福音。

但这不仅仅是王毅的真理。无数中国牧师讲述了面对法庭审判和官员质疑是向世界证明真相的道歉时刻。他们将迫害理解为让那些不经常与之交往的人——即中国社会阶层中的最高和最低层——知道福音的好时机。当他们被判处有期徒刑时,他们明白这是一个向通常最难接触到的监狱外的人——毒贩、妓女、赌博成瘾者和盗贼——宣讲福音的机会,这些人通常充斥着中国的监狱系统。中国牧师经常开玩笑说,他们的逮捕为中国监狱系统提供了牧师。当教会不把自己看作凌驾于主人之上,当它愿意走十字架之路时,它的辩证法就会开始看起来很像基督在世上的事工,向这个世界的统治者和最卑微的人证明了我们的信念。

但是,面对激烈的敌意,走上十字架的路不仅仅是教会的公开见证。十字架之路不仅是迫害中的公开见证。中国家庭教会宣称,即使在和平与繁荣的时代,这也是教会的道歉。即使在保护权利、遵守和平、中产阶级的美国,教会仍然与救主团结一致,救主许诺他的门徒将分担他在这个世界上的苦难。这一承诺应该成为我们公开见证的基础。

尽管他们一开始对世界有不同的理解,但王毅和邦霍弗最终都得出结论,教会的公开见证是公众遭受各种形式的痛苦所必需的。斯坦利·格伦兹和罗杰·奥尔森描述了邦霍弗对此事的看法,他们说:“他宣称,我们必须’把尘世上的杯子喝下来’,因为只有这样,被钉在十字架上复活的主才能和我们同在。”他们继续,

作为基督徒的这种参与意味着在世界生活中分享上帝的苦难。这个概念。。构成了 Bonhoeffer 思想的高潮。他认为,生活在世界上的基督徒成年后必须为世界历史承担全部责任。最重要的是,分享上帝的苦难意味着以真正的门徒的身份生活,在为世界服务时变得脆弱,遵循 “人为他人” 的步伐。因为 “只有当教会为人类而存在时,教会才是她的真实自我。”

同样,王毅认为,在成熟的世界中,教会的目的在某种程度上是作为一种分担负担的行为来分担痛苦。目标不仅仅是揭露人类的泥馅饼并让它陷入困境。教会参与世界的苦难,为世界的利益而努力。

王毅和早雨深受2008年四川地震的影响,不仅受到自然灾害的影响,还受到地震暴露的腐败和贫困的影响。2018年5月,也就是他被监禁前七个月,王毅被拘留了二十四小时。这恰好阻止了 Early Rain 在地震十周年之际举行追悼会。王毅于周六晚上获释,周日上午他宣讲了一篇非常激动人心的布道,题目是 “十字架之路,烈士的生平”。在这篇布道中,他解开了教会对苦难的呼吁,宣称:

整个国家,特别是我们这些生活在四川的人,都同感这次地震的苦难。当我们来到这里时,我们会分享痛苦,并在苦难持续的同时祈祷。苦难不是过去;苦难是一种持续的情况。为了纪念苦难,我们必须承担苦难的负担,因为我们要按照上帝的指示来分担负担。

Early Rain呼吁受苦受难的部分原因是呼吁他们认同他们的城市成都的具体负担。救赎并不能使上帝的子民脱离当地环境;相反,它要求他们与当地环境一起受苦。

王毅在其他地方说:“教会是当今世界的守望者。如果教会不指出世界的邪恶,那么教会将与世界一起受到谴责。教会是当今世界的代祷者。”对于王毅来说,走十字架之路使教会能够像基督本人一样看到和分担邻居的重担。

王毅并不是唯一一个这样思考的家庭教会领袖。在一篇关于这个话题的典范布道中,西蒙·刘用圣餐意象来强调基督徒与基督的结合以及对基督苦难的参与。他用耶稣的话描述了这种与基督的结合,即吃掉他的身体和喝他的血。通过以基督为食,基督徒会摄取和吸收主的DNA,从而与他合而为一。然后,基督徒与基督结合,成为献给世界的祭品。当基督允许他的子民以他为食时,他们反过来又允许世界以他们为食。因此,对于一个认为自己已经成熟的世界,教会的主要道歉是它愿意把自己当作圣体礼物来供世界赖以生存。

刘写道,

当你喝基督的宝血时,你自己里面就有基督的DNA。你的 DNA 承载着十字架的 DNA,你变成了这个世界的盐和光。。他首先让我们以他为食,品尝主恩典的甜蜜,然后他通过被吞噬,使我们做好准备,成为世界的祝福。

这里并不是用私有化、个性化的语言来理解痛苦。教会在世界上的公开见证并不是自私地注重自我保护。相反,正是上帝的子民为一个世界服务的企业经验,他们认为世界已经成熟,但实际上处于衰落状态。因为在国王回归之前,世界不会走向成熟。目前,世界只是一个坐在泥馅饼中的孩子,渴望吞噬下一个漂亮的东西。当我们等待上帝的国度成就时,当我们等待真正人性的启示时,教会要参与主的苦难,当它成为世界赖以生存的东西时,教会将尽最大的歉意。

我今天要问你:这种视角 —— 教会自称被吞噬时最好的公开证人 —— 是否标志着我们今天在北美的公开见证?当我们面对教会现在和将来在美国社会中的边缘化时,我们是否正准备好与主人一起走上十字架之路,以获得食物?还是我们在努力巩固我们的权力、文化声望和政治保护?

纵观教会的历史,我坚信最重要的道歉时刻,即改变文明结构的时刻,都发生在教会采取这种姿势时。从罗马斗兽场的第一批烈士,到圣帕特里克回到奴隶身边,再到路德的《我站在这里》,再到在中国各地献出生命的传教士,再到抵御伯明翰消防水带的黑人基督徒——所有这些例子告诉我们,如果不首先将教会的生活理解为牺牲的生活,你就无法为更伟大的现实作证。

历史上最强烈的道歉时刻到来了,教会为了证明现实而集体遭受苦难,这要么是因为世界已经把它压到那个地步,要么是因为教会主动地代表世界自首。正如当今中国的家庭教会提醒我们的那样,教会公开见证的最重要组成部分是一群信徒,他们愿意献出生命来见证上帝在他的儿子里向我们启示的一切。

Eighty years ago this year, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was arrested in Nazi Germany by the Gestapo. He was first held in a wartime prison and later transferred to a concentration camp. He was executed shortly before the end of the war. Halfway around the world and seventy-five years after Bonhoeffer’s arrest, another pastor was arrested in southwestern China and sentenced to nine years in jail, the longest sentence given to a house church pastor in recent decades. For five years now, Wang Yi has slept, awoken, eaten, and struggled through the day in his own prison camp, suffering for the same reasons given his brother from a former century and different nation—subversion of a state seeking the ultimate allegiance of its people.

When I realized that 2023 marks these two anniversaries in the history of political dissent, religious freedom, and apologetics, I decided to revisit some of the questions Bonhoeffer asked at the end of his life about the nature of the church, and to consider the answers being given by a Chinese pastor who is more truly continuing his legacy than anyone in the Western world can claim today.

The ongoing dismantling of Christendom as well as the loss of traditional Christianity’s cultural cache in the West has many leaders scrambling to figure out what the public witness of the church should look like, particularly in the United States. Though he lived one hundred years ago, Bonhoeffer was not unfamiliar with this conundrum. He lived and was educated in the German intellectual milieu that predicted and helped create the world in which we now find ourselves.

As he wrote prison letters and faced his eventual demise in the context of early twentieth-century totalitarianism, Bonhoeffer concluded, with the best of German philosophy and theology, that humanity had changed. Men and women no longer feel any need for God and no longer need him to answer their unanswerable questions. He wrote, “Humans now operate autonomously, without sensing a need to refer to either divine grace or divine truth. In the world come of age, people no longer require God as a working hypothesis, whether in science, in human affairs in general or increasingly even in religion.” Humanity had grown up, and Bonhoeffer was left with a question: What is the point of the church in a world come of age?

This is a controversial question coming from a martyr whom evangelicals love to honour. Many describe Bonhoeffer’s prison writings as the result of great duress, almost deeming his belief that the world has come of age the result of a labor camp–induced psychological breakdown. Regardless of where one lands historiographically on Bonhoeffer’s mental well-being and its impact on his writings, the idea that the world has come of age, in its own estimation, seems a given to me in the twenty-first century.

One doesn’t need to believe that the world in actuality has come of age and that all of our science and technology has actually closed the gaps in human need, whether spiritual, emotional, mental, or physical, to be compelled by the idea that humanity believes this to be true. As we approach a century of secular development since Bonhoeffer’s claim, I find it an apt description of how the modern world understands itself. As a psychological description of the secular world, Bonhoeffer’s observation has me convinced.

So, then, what is the point of the church in such a world?

Today in the American evangelical church we find a variety of responses to our cultural marginalization at the hands of a world come of age. On one end of the spectrum we find an alarming resurgence of interest in and commitment to Christian nationalism as the church’s best posture. On the other end we find a capitulation to the definitions of meaning and identity given to us by our society’s thought leaders and culture makers. And in the middle we find a confused cacophony of voices who say that if we just argue more clearly, advance more digitally, publish more frequently, and influence more savvily, we can somehow turn a tide that we were decades late in identifying, let alone addressing.

But elsewhere in this world, different answers are being offered.

Like his German predecessor, Wang Yi lives and ministers in an advanced secular context, seeking to carve out space for the church in a totalitarian society that allows for no public sphere or open speech. What Bonhoeffer believed in the early twentieth century about humanity’s modern self-sufficiency and lack of need for the church to provide answers, the Chinese (almost 20 percent of the world’s population) live and teach as authoritative reality. This is not to suggest twentieth-century German secularism is equivalent to that of twenty-first-century China. But as one of the world’s most officially atheistic societies for almost a century, China is an important part of a world that believes it has come of age. Abandoning the imperial cult, folk religion, and older forms of Confucianism to pursue science and technology, and eventually capital, as the answers to all human and social problems, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long taught its people that Chinese society has “grown up” compared to all preceding history. Since the 1920s, the eradication of inherited meaning and purpose has been the CCP’s expressed goal.

But whereas Bonhoeffer concluded that the church was obligated to adapt in order to testify of God and the way for men and women to enter relationship with him, Wang Yi seeks to proclaim that in a world come of age the purpose of the church is to contradict the world’s understanding of itself. He uses the metaphor of a masterful ballet dancer who must perform on a stage in the middle of a landfill. The contrast between the performance and the stage is intended to provoke the audience to understand the need for the landfill to be made new. Wang Yi writes,

The key is faith, and faith needs a stage. Faith is like a master ballet dancer dancing gracefully on a dilapidated stage. On the one hand, as long as the dance is beautiful, what does it matter if the stage is in tatters? Alternatively, imagine how glorious and resplendent it will be the day this master dancer performs on a magnificent stage. For now, however, God says that the value of the dance must be expressed on a dilapidated stage.

He says also,

Let me remind all of you once again that our government is ambitious. Their goal is not only to obtain order in society, but to monopolize the meaning of landfills and subway stations. As such, the government is concerned when we dance ballet at landfills. We will find police officers pinning us to the ground when we play the violin in the subway. However, this is part of the meaning of the landfill, for God has allowed them to be ambitious because he wants to magnify the value of faith. In general, the more terrible the performance environment, the greater the “eschatological meaning” of the church’s show.

Unlike Bonhoeffer, Wang Yi and many of his peers in the house churches view the process by which the true humanity is revealed as necessarily a process of contrast and antithesis.

The world’s true coming of age is not dependent on humanity’s perception of itself. To say that humanity can actually come of age in this world brings to mind C.S. Lewis’s illustration of humanity as a child content to play with mud pies in the street when he has been offered a trip to the seaside. For Wang Yi and those in his theological movement, until the arrival of the eschaton, when the true humanity does come of age and the kingdom of God is consummated, the church exists as a resplendent show to testify precisely to the fact that we have not come of age, that humanity is still content with its mud pies in whatever era it finds itself.

According to many in the Chinese house churches, including Wang Yi, the most significant apologetic moments revealing humanity’s state to itself take place when the church is willing to “walk the way of the cross.” To testify to the reality of the kingdom of God necessarily involves the call to suffer with Christ. The ballet that the church dances is not one of triumph and power; it is a dance of collective suffering and sacrifice, a dance that Bonhoeffer himself knew well, though perhaps was unable to understand in the terms the Chinese house churches have come to use.

Wang Yi says,

How do we show that we are motivated by faith, not by political goals? We must be willing to take the way of the cross and suffer for our faith. . . .

This is the way of evangelism and apologetics. The church has an opportunity to contend, persevere, and pay the price for our faith in front of society and its rulers. If this is the first nation-wide persecution of house churches in the last twenty years, it is also the church’s first evangelistic and apologetic opportunity in the last twenty years.

What do you have to believe to say that when hardship comes to the church, its suffering is its greatest apologetic and evangelistic moment? Greater even than efforts made in comfort, power, and celebrity? These are the questions that fill my mind as I look ahead to the rest of this century, whether or not it does prove in the end to be the Chinese century.

The Chinese house church was born in suffering and hiddenness. Accordingly, it has not been considered noteworthy for contemporary apologetics. But we ought to reconsider and give it its due. Though we have often othered the Chinese house churches and distanced their reality from ours, their legacy is less one of miracles among bamboo forests and more one that recalls the legacy of Bonhoeffer: stubborn commitment to the universal church in the face of nationalizing forces and an unwillingness to give allegiance to a power that claims to represent the world come of age.

Contrary to common misconception, when the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949, it did not abolish religious practice. Instead, it simply required that all religions demonstrate their patriotic support for the new government and submit to the oversight and regulation of the governing authorities. Eventually, this effort was consolidated in a state church called the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSMP). Apart from the most intense decades of the Cultural Revolution, the CCP has never attempted to stop religious practice from existing in China; it simply requests that Christians submit to its authority. The party wants the love and allegiance of its people.

You can love both God and country, right? In the early 1950s roughly half of the Christian population of China decided that, yes, this was possible. After a century of Western and Japanese imperial forces walking all over China, Christians were compelled by the Communists’ ability to restore the sovereignty of their country. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese Christians signed a document called “The Christian Manifesto,” pledging their love for China and allegiance to the government.

But the other half of China’s Christian population said no. Figures such as Wang Mingdao, long known for his rejection of missionary oversight for China’s newly forming indigenous churches, maintained that only Christ is the head of the church. There cannot be any state authority over the inner life of the church, and the first generation of house church pastors chose to lose their political protections and rights in order to maintain this definition of the church. This is what became what we now call the Chinese “house church.” House churches are not defined by where they meet or how they meet; what defines them is their unwillingness to enter the state church.

After China began opening again in the 1980s, it seemed like it was trending more and more toward non-regulation of religion. As Christianity exploded across China’s urban centres from the 1990s through the early 2000s and into the 2010s, there was increasing toleration of the house churches, especially in the wealthiest, most stable cities along China’s coast. The term “house church” really couldn’t be limited to a church meeting secretly in a home. After all, congregations of five hundred people meeting on Sunday morning in rented commercial space called themselves 家庭教会 (jiating jiaohui), or “house churches.” They were still very much illegal, but they were more or less tolerated if they didn’t disturb the peace.

According to Wang Yi, when there is opposition, churches ought to be willing to give up their civil rights, legal stature, physical property, and money. But what the church must never give up is its doctrine, the sacraments, and the offices of the church.

In 2018 this changed when the CCP implemented a new set of religious regulations. The emphasis has been on limiting all religious gathering to the TSPM, and there has been a noticeable increase in harassment and persecution of house churches, along with many other forms of religious expression across China. The arrest of Wang Yi in December 2018 and the violent attack on members of his congregation, Early Rain Covenant Church, was one of several signals that year that persecution would increase under Xi Jinping. This was made doubly true during the Covid-19 pandemic when Xi’s Covid Zero policy was used harshly against house churches. Though the current situation is nowhere near the persecutions of the twentieth century, this is generally considered the harshest crackdown since the earliest days of the house church in China.

A friend of mine is a Chinese church planter in a major Chinese city. His baby church launched a few weeks into the breakout of Covid-19, right after the Wuhan lockdown. One short year later, their church had grown from a dozen people to one hundred, and on their first baptism Sunday they baptized six adults and nine children. Now, in their second year of existence, they are already moving ahead with planting a whole new church. And this has been against the backdrop of submitting fully to the government’s oppressive Covid Zero policy, and all of the much more mundane pressures of living in one of the world’s most urbanized, digitized, secularized, and competitive cities. The pressures they face as the church outweigh anything we experience here in North America.

The World Christian Encyclopedia states that in 1970 there were fewer than one million professing Christians in China, or 0.1 percent of the population. The number it lists for today is 112 million, almost 8 percent of the population. Even allowing for the massive growth of China’s population at the end of the twentieth century, that is a sixtyfold growth of professing Christians in China. Since the birth of the house church in China, it has grown—without political protections, public platform, or recognized institutions. If we want to learn an apologetic for the predicted pressures that will be put on the twenty-first-century Western church, we should consider what a church that has not only survived but exponentially grown under seventy-five years of oppression can teach us.

In establishing its foothold in China, the CCP declared modern Chinese society to be part of a world that had come of age. The house churches have suffered for seven decades in order to deny that description of reality.

They teach us that the public life of the church must be a cruciform one. God’s grace unites the church with Christ, and in this union the church necessarily participates in the suffering of Christ. One house church leader I know points to Matthew 10:24 to explain. She reminds us that the servant is not above the master, nor the student above the teacher; therefore, if our master and teacher’s life in this world was marked by suffering, the church ought to anticipate the same.

Wang Yi describes the cruciform nature of the church’s public witness in the following way:

How then do I manifest an invisible world? How do I show my true wealth in this life? I show it through poverty. How do I display resurrection power? Through suffering. I have the ability to suffer. I can give because I have. What I give testifies to what I have. . . .

So Christians witness for Christ in this world through the subversive means of the cross. My life, God’s creation, and the entirety of world history are all unfinished. The cross means you build your hope on the future instead of realizing it in the present.

In this statement, Wang Yi gives a cosmic, eschatological dimension to the church’s call to suffer with Christ. The willingness and readiness to walk the way of the cross is a necessary distinctive of the church’s public witness. He goes so far as to argue that the church fails to participate in the life of Christ and denies his lordship if it lacks the willingness to be known by and identified with suffering.

Calling to mind some aspects of Bonhoeffer’s warnings regarding “cheap grace” and the religious comfort that tempts many Christians, Wang Yi believes that walking the way of the cross is necessary for the purity of the church’s mission. When you hear people talk about their fears regarding the marginalization of the church, what do you most frequently hear them discuss? Certainly, we’re confronted with a wide variety of issues, many of which centre on issues of biblical anthropology (human sexuality, abortion, euthanasia, etc.) and the rights of conscience. But there is a persistent fear among many regarding the church’s tax exemption status and property rights. Many are quick to associate physical assets with the freedom of the church.

Wang Yi argues that the church ought to fight, but he does not believe in fighting for the things many Americans are keen to protect.

Wang Yi is not saying here that Christians are not called to work for better systems and political protections; he is simply arguing that the church ought to be crystal clear about what God has tasked the church with protecting when push comes to shove. And while certain rights can be accurately understood as products of a society that understands and values the role of religion in general, and Christian churches in particular, they are not what defines the church. According to Wang Yi, when there is opposition, churches ought to be willing to give up their civil rights, legal stature, physical property, and money. But what the church must never give up is its doctrine, the sacraments, and the offices of the church.

There are multiple ways to provide political protection for the church, including constitutional democracy, but Wang Yi maintains that Christian nationalism is not the solution. Besides, every historical example of a “Christian nation” that I can think of has itself ended up persecuting the church in some manner at some time. If we are not Christian nationalists, then we must disciple in a way that prepares our churches for counting the cost for what God has actually told us to protect, instead of the many protections we might believe necessary for the success of the church.

In times of duress, the church must be willing to give up its civil rights to maintain the purity of its mission. To have a public witness, the church must fight for what truly defines it. Wang Yi reminds us that tax exemptions and church buildings are not the church. To testify to its true nature, the church must be willing to give up all its rights as its master, Jesus, did. I suspect that all the things some American churches are afraid to lose are the things Bonhoeffer would point to as the trappings behind which cheap grace hides. Wang Yi points to that which is necessary to leave behind in order to refine and purify our allegiances and loves, and to ensure the church understands the costly nature of discipleship.

Wang Yi argues that the way of the cross is necessary for testifying to the truth of the gospel. As already stated, according to Wang Yi, this is why the church grows under duress. Wang Yi’s primary hope in the months before his arrest was that he would be able to speak at his own trial and publicly declare his beliefs. He wanted to proclaim the gospel to the judges, lawyers, and officials in the courtroom.

Wang Yi argues that the way of the cross is necessary for testifying to the truth of the gospel. As already stated, the way of the cross is the way of apologetics. The more the church is persecuted, the more it testifies to the world about the kingship of Christ.

But this isn’t true only of Wang Yi. Countless Chinese pastors have recounted facing courtroom trials and questioning by officials as apologetic moments to testify to the truth before the world. They understand persecution as an opportune time to make the gospel known to those they would not frequently engage with—the highest and lowest among Chinese social strata. When they are sentenced to time in jail, they understand it to be an opportunity to preach the gospel to those often most difficult to reach outside jail—the drug dealers, prostitutes, gambling addicts, and thieves that generally fill the Chinese jail system. It’s a common joke among Chinese pastors that their arrests provide the Chinese prison system with its chaplains. When the church does not view itself above its master, when it is willing to walk the way of the cross, its apologetics begin to look a lot like Christ’s ministry on earth, testifying to what we believe to both the rulers of this world and the lowliest.

But walking the way of the cross is not just about the church’s public witness in the face of active hostility. The way of the cross is not only a public testimony in the midst of persecution. The Chinese house churches proclaim that this is to be the church’s apologetic even in times of peace and prosperity. Even in rights-protecting, peace-abiding, middle-class America, the church remains united to a Saviour who promised that his disciples will share in his sufferings in this world. This promise ought to form the foundation of our public witness.

Though they start with different understandings of the world, both Wang Yi and Bonhoeffer ultimately conclude that the church’s public witness necessitates forms of public suffering. Stanley Grenz and Roger Olsen describe Bonhoeffer’s views on the matter, saying, “We must ‘drink the earthly cup to the lees,’ he declared, for only in so doing is the crucified and risen Lord with us.” They continue,

Similarly, Wang Yi argues that the point of the church in a world come of age is in part to partake in its suffering as an act of burden sharing. The goal is not simply to reveal humanity’s mud pies and leave it in its misery. The church participates in the world’s misery and offers itself up for its good.

Wang Yi and Early Rain were deeply affected by the Sichuan earthquake of 2008—not only by the natural disaster but by the corruption and poverty that the earthquake exposed. In May 2018, seven months before his incarceration, Wang Yi was detained for twenty-four hours. This happened to deter Early Rain from holding a memorial service on the tenth anniversary of the earthquake. Wang Yi was released on Saturday night, and on Sunday morning he preached a highly emotional sermon titled “The Way of the Cross, the Life of the Martyrs.” In this sermon he unpacked the church’s call to suffer, declaring,

Part of Early Rain’s calling to suffer is a calling to identify with the specific burdens of their city, Chengdu. Salvation does not remove God’s people from their local contexts; rather, it calls them to suffer alongside their local context.

Elsewhere Wang Yi stated, “The church is the watchman for today’s world. If the church does not point out the evil of the world, the church will be condemned along with the world. The church is the intercessor for today’s world.” For Wang Yi, walking the way of the cross enables the church to see and share in the burdens of its neighbours, as Christ himself did.

Wang Yi isn’t the only house church leader thinking along these lines. In one exemplary sermon on the topic, Simon Liu uses eucharistic imagery to highlight the Christians’ union with Christ and participation in his suffering. He describes this union with Christ with Jesus’s words to eat his body and drink his blood. By feeding on Christ, the Christian ingests and imbibes the Lord’s DNA, thus becoming one with him. Then, in union with Christ, the Christian becomes an offering to the world. As Christ allows his people to feed on him, they in turn allow the world to feed on them. Thus, the church’s primary apologetic to a world that believes it has come of age is its willingness to offer itself as a eucharistic gift on which the world may feed.

Liu writes,

Suffering is not here understood according to privatized, individualized language. The church’s public witness in the world is not a selfish focus on protecting itself. Instead, it is the corporate experience of God’s people in service of a world that believes it has come of age but in fact is in a state of decay. For the world will not come of age before the return of its King. For now the world is simply a child sitting among its mud pies, hungry for the next pretty thing to devour. As we await the fulfillment of the kingdom of God, as we await the revelation of the true humanity, the church is to participate in the Lord’s suffering, providing its best apologetic when it becomes that which the world feeds on.

I ask you today: Does this perspective—that the church’s best public witness is when it offers itself to be devoured—mark our public witness in North America today? As we face the present and future marginalization of the church in American society, are we gearing up to be fed on, walking the way of the cross with our master? Or are we striving to shore up our power, cultural prestige, and political protections?

Scanning the history of the church, I’m convinced that the most important apologetic moments, the ones that altered the fabric of civilization, all took place when the church adopted this posture. From the first martyrs in the Colosseum, to St. Patrick returning to his enslavers, to Luther’s “here I stand,” to the missionaries who laid down their lives across China itself, to the black Christians who withstood the fire hoses in Birmingham—all these examples teach us that you cannot testify to a greater reality without first understanding the life of the church as a life of sacrifice.

The strongest apologetic moments in history arrive when the church collectively suffers in order to testify to reality, either because the world has pressed it to that point or because the church has proactively given itself up on behalf of the world. As the house churches in China today remind us, the most important ingredient of the church’s public witness is a body of believers who willingly lay down their lives to testify to what God has revealed to us in his Son.