B

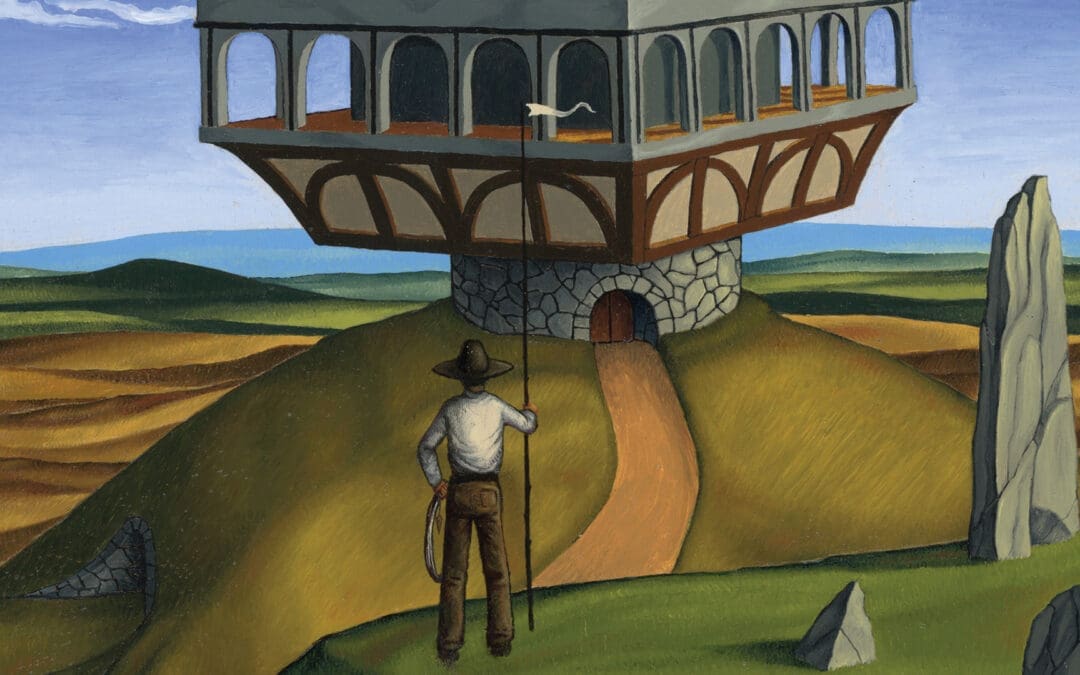

Books were once written on expensive animal skins. This meant that even before the words were written, a “book” had a material value. If the words of a particular book were deemed too common, a scribe might erase the parchment in order to copy a second or even third book on the same skin. These books, called palimpsests, became legible accounts of the progression of a culture’s values. As older texts were erased to make room for newer editions, what was retained was not only the text but also the imprint of what had been written before and deemed redundant.

Images of Christ serve as a palimpsest of sorts. They reveal what a culture values in its attempt to represent Christ. Does he look like a first-century Jew? Does he look like a European? Does he look like us, whoever we are? As cultural values shift, so too do religious expectations—and images follow along.

The earliest depictions of Christ are symbolic more than representational, seeking to communicate his role, not his features. From these symbolic images came a flood of similar representations that sought to communicate his power, his regency, and his rule over the natural world. Neither Christ’s eyes nor the shape of his brow contained any particular significance. The goal of these artistic representations of Christ was to communicate who he was, not what he looked like.

Images of Christ serve as a palimpsest of sorts. They reveal what a culture values in its attempt to represent Christ.

Later images of Christ, especially those from the modern era, reveal quite a different set of concerns. Because the modern concerns of individual identity closely nest who a person is with how they appear—whether in terms of their gender expression, racial identity, or performance of beauty or social status according to dress and presentation—what the image of Christ looks like has taken on a heightened significance. Depicting Christ’s physical features explicitly or implicitly makes a judgment about his ethnicity and how his features may reflect his family of origin. Such representation has a political import insofar as it may allow members of a particular group to identify Christ as a member of their own group, as “one of us.” If Christ shares a closer kinship or identification with them than with others, they can claim a solidarity between Christ’s cause, too, and their own.

But because images are thought to depict identity, and because identities are numerous, there is a tension at the heart of any depiction of Christ. Who, or what, does he resemble? And is he therefore more like some than others? Whose side, after all, is he on?

How Should Jesus Be Drawn?

Once images of Christ became common, they proliferated. Some argue that the sheer preponderance of images is in fact a shield against their idolatrous use. If there are so many images, then no one image will be considered exclusive. Pseudo-Dionysius makes a similar argument relative to speech about God. You might call God everything, thereby realizing that God is no one thing. So too with images—you might depict God as like all of us in order to avoid making an idol of any one depiction.

So the Chinese artist He Qi depicts Christ calming the waters with facial features that borrow from Asian art. John August Swanson’s Last Supper depicts Christ and his disciples as bearded and dark-skinned. So, too, Paul Harvey and Edward J. Blum note in their book The Color of Christ that images of a light-skinned Christ were often used to reinforce “white” identity, even as Jesus’s phenotype likely had resulted in a darker skin tone. They write of liberation theologian Virgilio Elizondo, who spoke of a Christ who “was a mestizo. And we dare say that to those of his time, he must have even appeared to be a biological mestizo—the child of a Jewish girl and a Roman father.”

Elizondo (assuming the falsity of the virgin birth) contextualizes Christ’s personal history in order to relate him to the story of his people. In one of the most moving images of Christ from recent years, artist Kelly Latimore does the same. He offers a depiction of George Floyd as a modern Pietà. In this gripping image, Floyd reclines on his mother, his eyes closed in death. His mother—like Mary, the one whose womb brought forth the redemption of all things—holds him close and looks directly at the viewer, as if asking them to share in her sorrow. All the emotion of the Western Pietà type is brought to bear on Latimore’s depiction of Floyd and his mother.

Here, of course, is the place where tension arises. Latimore’s depiction rings true in its communication of the tragedy of Floyd’s death—he an innocent sufferer—and the grief it caused those who loved him. And it truthfully portrays the sorrow of Mary, whose grief over her lost son calls to the deepest part of the soul. But its truthfulness is strained when it makes Floyd in the image of the dead Christ. Is not such a role the wrong one to ask of Floyd? Might it be too heavy a burden to ask him in his death to restore all things? This question remains difficult to write about, as the death of George Floyd was itself so terrible, and so common. But in making an icon of Floyd, are we not making of him also a spectacle—a symbol of suffering that in itself is irredeemable? Are we leaving him and his mother stuck in an embrace that leads the viewer to perpetually gaze at endless sorrow?

Christian images are supposed to move the viewer to contemplate a religious truth—that in Christ, the man for all, death will be undone. For this very reason, the synecdoche does not work both ways: Paul’s statement that one man died for all does not mean that the death of all men is as this one. There is a fundamental dissimilarity between our suffering and Christ’s, for only in his death is death undone.

For Christ, death at the hands of the state becomes instrumental, a means to making him the seed of new life, a means to a new polis and a meaningful affront to empire. But only Christ’s death is such an instrument. All other deaths may participate in his with their own promised resurrection. But no other death bears such a weight.

The depiction of Mary’s sorrow, with which we are to identify, is not only the story of a mother who grieves her dead son. It is also the picture of a mother whose labour pains birthed the new creation. Such a transformation is too much to ask of any other creature. Even if Latimore’s image is seen as a modern Pietà, it certainly matters that Floyd will not be returned to his mother. Mary’s offering of her beloved son was for the redemption of the world. Though this might be imitated, it cannot be replicated.

It may seem unnecessarily unkind or even political to discuss Latimore’s modern icon with such a critical eye, the picayune critique of an academic with an axe to grind. But there is much at stake in making Floyd, or any discrete human, a type of Christ. Throughout history, visual representations of Christ and Mary have been used for political ends. Constantine famously led soldiers into battle with the Chi-Rho (a Christian symbol formed from the first two letters of the word “Christ”) emblazoned on his shield, indicating his alliance with the divine himself. The Crusaders of the Middle Ages also identified themselves as Christ’s warriors by marking themselves with a cross. The Nazis used a thoroughly de-Judaized Jesus to articulate their own vision of Christian history.

Artists also use images of Christ to query assumptions about gender and sexuality. In 1984, Edwina Sandys’s Christa was installed at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine. “Christa,” a female figure with prominent breasts and hips, is displayed on a cross. With her head tilted slightly and her eyes cast down, there is nothing inherently blasphemous about the image—it retains the gesture and posture of the crucifix entirely. One could easily transfer one’s religious devotion to the image of “Christa” to a more traditional Christ. The only wrinkle is that it is a woman, not a man, who is borne on the cross. In a 2023 essay for Comment, Wesley Hill writes of artistic images of an “ambiguously gendered” Christ by the artist Henri Maccheroni—images that seek to provoke viewers to imagine Christ identifying with their bodies, regardless of their own biological sex.

If in looking at Christ crucified we see primarily social change we can believe in, we have made of Jesus a slogan, a tool for our own cause.

Beyond commenting on their abundance, what might we make theologically of such images? I’d like to consider whether the preponderance of such images might bring with them a subtle danger—that of making Christ himself an instrument, to be used for our own social gain. If in looking at Christ crucified we see primarily social change we can believe in, we have made of Jesus a slogan, a tool for our own cause. He then ceases to be a correction of our values or our priorities and serves instead to confirm them. Religion loses its ability to call us outside ourselves and makes even Christ a means.

Christian theology has long struggled with the “scandal” of Jesus’s particularity. The scandal is that Christ became a particular man—this one and not another. In doing so, does he not identify more closely with those who resemble him? Does his embodiment show a preference for men, or Jews, or Galileans?

Ignoring Christ’s particularities, whether his Jewishness or his maleness, comes easily to those who see him primarily as a universal principle. According to this interpretation, what really counts for individual Christians is the way in which life with God is modelled by Christ himself, in whose example they are to follow. Jesus loved the poor and the outcast, so we should as well. Or Jesus showed the way to personal enlightenment by self-sacrifice, and we should do the same.

This interpretation may in itself not be a problem. It is indeed a good thing to love the poor and marginalized, and sacrifice may indeed be the path to personal enlightenment. But reducing Christ to a universal principle—of generosity, sacrifice, or neighbour love, among others—makes him less of a person. Instead of being flesh and blood, he becomes an example or an idea. His features can then be filled in however we’d like, as with a colouring book. And fill them in we do!

Jesus’s Jewishness has been read by some theologians as itself “translatable.” “Jewishness” becomes really a signpost for the “socially vulnerable” or “enemies of the state.” Beyond being oversimplified (and frankly anti-Semitic), this sort of move is an example of the evacuated Christology that treats Christ as a principle to be filled in however we’d like. It makes Jesus a palimpsest as we write over his historical particularity with our current social concerns.

In an essay for the Christian Century, Brad East clarifies what this does and doesn’t mean, drawing on the work of James Cone to argue that Jesus’s blackness is a logical non-step from his Jewishness. East writes that Jesus’s solidarity with the oppressed

is what licenses the iconography of Jesus as Black. It’s not that such visual tokens, rooted in such a confession, conscript Black people in toto into a symbolism not of their choosing, much less reify them into a monolithic victimhood. . . .

And as we have seen, its particularity is the very source of its universality: it does not deny but begins from the fundamental truth that the humanity of the God-man encompasses all people. Yet in our time, in this land, it insists that this comprehensive scope must not render Jesus in generic, unrecognizable skin—much less the pale hues of Warner Sallman. In offering a glimpse of who Jesus was and is for us, it forbids the gaze that would turn away from the wrongs inflicted against his body here and now, each and every day. For Jesus was a Jew; and because Jesus was a Jew, Jesus is black. Each interprets the other.

East is certainly right that God invests himself in righting the wrongs of this world in a preferential way, making the cause of the oppressed his own (Matthew 25:40–45). He is also correct that there is nothing heretical about making images of such a depiction, for indeed such images prove instructive in cultivating our imaginations regarding the sorts of ways God works on creatures. At the most basic level, they affirm that God is for us.

And yet such depictions shout where they might gesture. The risk of depicting Jesus as black, or Christ as George Floyd, is in using Christ’s Jewishness as an instrument. Whether it is on the question of race or gender or other markers of identity, such images inevitably trade Jewishness for a particular identity that Jesus is thought to elevate, making Christ’s incarnation nothing more than a means of social disruption. That Christ came as a particular person to a particular people is part and parcel of God’s work with Israel. Jesus’s Jewishness is written into God’s ways with Israel, the scarlet thread that bound God’s covenant with Abraham to God’s work in Christ. Rendering such a particularity conveniently replaceable makes the stories of our own needs interchangeable with God’s initial covenant, our own social disruptions and sorrows those that God came to bear. Can we see ourselves as beneficiaries of God’s covenant with Israel without attempting such an iconographic colonialism, without making this covenant all about us? For it was to another people in another place that God came. Rendering Jewishness a means to Christians’ own ends risks being the next stage in a long history of Jewish replacement by Christian theology. It makes Jewishness an instrument, and the Son of God a tool.

Moving Beyond Instrumentality

In 1305 a controversy erupted over what was called a Crux horribilis, a terrifying cross, which was installed at the chapel at Conyhope. The crucifix lacked a crossbeam, and so Christ was set on it with his arms in a Y shape. This Gabelkreuz (“plague cross” or “pall cross”) was not unknown in Germany and Italy, but its presence in England generated a giant response. Crowds flocked to venerate the crucifix, causing the local bishop no little worry.

His concern was that while devotion to a true likeness was appropriate, devotion to a false likeness was, in the words of medieval historian Paul Binski, potentially “damaging to men’s souls.” Classically informed images of the crucifixion, he reasoned, assumed an “effortless relation” between the good and the beautiful and depicted the crucifixion in ways that were immediately recognizable. If Christ was easily known in the depiction, then heretical teaching about Christ could be prevented and the piety of the individuals venerating the image would be holy and upright piety.

In the bishop’s estimation, the Conyhope crucifix, by diverging from common and accepted depictions at that time, threatened to generate among the “indiscreet populace” a similarly divergent piety. “For the avoidance of peril to man’s souls,” the crucifix was removed from the chapel. The “peril” would be ascribing honour to a crucifix that caused viewers to focus on the wrong thing.

If indeed the “flesh” that Christ took on is interpreted in each Christian who follows him, there is a Christian permission to interpret Christ widely. In seeing Christ as George Floyd, we can recognize that the grave injustice that has been visited on black Americans is not forgotten by God. And yet, as I’ve argued, in doing so we risk making Christ into an instrument, a means of communicating and achieving our own social ends. In an age when modern technology mediates the human relationship to the world, it can be difficult to conceive of anything apart from its utility. A good thing is a useful one. Religion, too, can fall prey to this mindset, and so the instinct to communicate the good of a faith can depend on our ability to communicate its utility.

But God is not useful. This is not the same thing as saying that he is of no use, for indeed the benefits we receive from Christ are significant. And yet in a technological age there is a particular risk of making images of Christ that function as little more than advertising. If our images of Christ are a palimpsest of sorts, what might be discovered is an accelerating preference for images that not only make Christ look like those who depict him—after all, this has been common throughout most of history; look at any Renaissance painting—but also reduce Christ to our political concerns. Restoring a different view of Christ—moving our thoughts from his works to his person—will be quite an excavation. But without it there is danger ahead—for when God becomes an instrument, humanity becomes merely a means.

For this was the great tragedy of George Floyd—that he was treated by the Minneapolis police not as a particular man but as a general principle, as a threatening presence and not someone with a story of his own. To make his image now an instrument of our ideology repeats how he was tragically treated in his death—as a tool, as a principle, but not as a person. To honour his legacy, we should not make him a means.