I

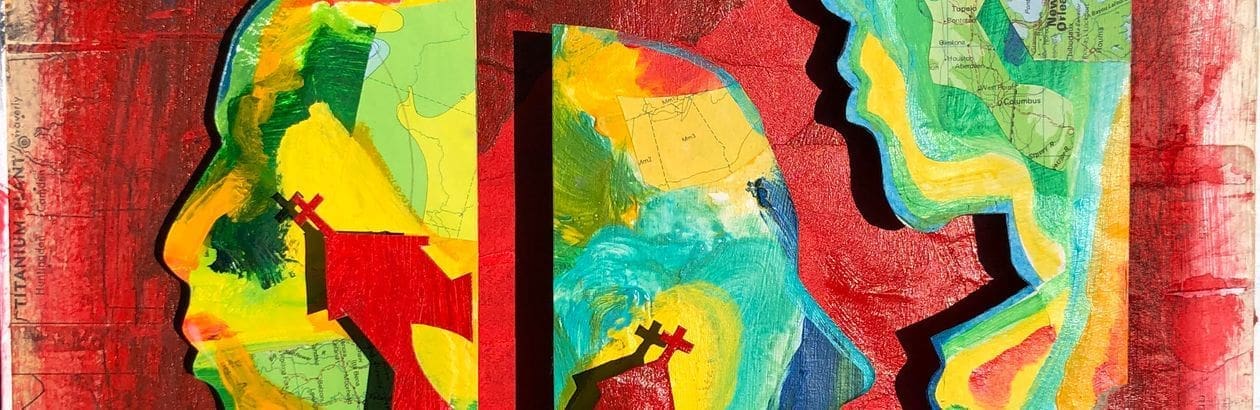

Immigrants are nonentities, residing in a purgatorial state between existence and non-existence in the American psyche. Everyone knows that immigrants exist—the stock image of them coming over borders, a faceless mass—but few seem to wonder about the individual souls attached to the hands that mow American lawns, take American blood pressure, clean American homes, deliver steaming-hot Styrofoam containers of cheap eats to American doorsteps. What happens when the business day ends and these hands come to a halt?

Religious forecasters predict that the future of American Christianity will be powered by these souls. Fifteen percent of those in the US are foreign born, and their children are increasingly making up more and more of the native-born population. The Pew Research Center has found that 68 percent of immigrants to the US are Christians, 12 percent profess other faiths, and 20 percent are “nones.” Walk into a service represented by any one of these trend lines and chances are you will see the same hands, this time in a state of uplift, singing hallelujah.

But these congregations feel like ghosts when it comes to conversations about the state and health of American religion. In the grand debates going on about nones and the “negative world,” pluralism and Christian nationalism, immigrant churches don’t conform easily to the categories. Some of this is a data-collection challenge: online maps tend not to show their locations as many immigrants worship in repurposed spaces—a congregant’s home, a local business. Some of this is because immigrant churches are uniquely multivariate; there is no such institution as “the immigrant church.”

These churches instead have to rely on parallel immigrant networks to inform others of their existence. And while American Protestantism has been defined for decades by the tripart taxonomy of mainline, evangelical, and black, the way immigrant churches interact with this pie chart exists in a constant state of flux. For example, there has been much coverage on how Latinos are the fastest-growing group of evangelicals in the United States, shattering assumptions of their loyalty to Catholicism. Yet the public imagination has not yet disentangled “evangelical” from its cultural stereotype of white Republicans in flyover states. The term “evangelical” itself is going through a reckoning. Will it be restored as an adjective describing a distinctive flavour of faith, encompassing all who identify as born-again Christians? Or will it splinter into separate categories based on various ethnic-inflected theological folkways—white evangelicalism, Latino evangelicalism, Asian evangelicalism, and other subdivisions?

The public imagination has not yet disentangled “evangelical” from its cultural stereotype of white Republicans in flyover states.

What I’d like to do here is focus less on the temporal hope for dying congregations from new “immigrant fuel,” itself a sociological reduction, but rather zoom in on one particular immigrant context—my own—so as to illuminate the complex dynamics of generational faith inheritance and the push-pull of spiritual, political, and cultural forces in the contemporary American experience.

I am the son of two immigrant pastors. The church my parents lead and that I grew up in is called Tian Fu United Methodist Church. “Tian” means sky and “Fu” means blessing; Tian Fu refers to a heavenly blessing. The first two words, being Chinese, signify the ethnic nature of the church, while the last three words are in English, signifying its affiliation with the largest mainline denomination in America. Taken as a whole, the name captures the approach the church takes to bridging the cultural divide.

Services are solely in Mandarin, which makes the task of evangelizing to non-Mandarin speakers impossible. But because of the language limitation, the church is also able to retain a distinct cultural flavour while creating a pathway for congregants to immerse themselves in American culture. So while the language barrier limits opportunities for proselytizing to America at large, it has the paradoxical effect of being able to attract even more congregants from within the barrier, as services end up feeling tailored to a specific audience rather than staking out a one-size-fits-all approach.

In a conversation my parents had with a prominent figure in the United Methodist Church, he noted that the only churches growing at a rapid clip were those that did not offer services in English, especially Chinese and Ghanaian churches. Meanwhile, the Korean churches have stagnated in growth due to reduced immigration. While the language barrier seems like it could limit the number of congregants, it has actually helped churches flourish, as new immigrants are drawn to an institution that fits their specific needs.

English-speaking pastors from other Methodist congregations are often invited to preach, where their sermons are translated into Mandarin sentence by sentence. Very few in the congregation actually know English well enough to listen to a whole sermon, so the purpose of inviting English-speaking pastors is to make the congregants feel like they are getting a taste of what being a “real American” encapsulates.

There are, of course, thorny questions as to what exactly constitutes the “real American” that immigrants are expected to become. For example, same-sex marriage is legal in America, yet many immigrant pastors come from cultures opposed to same-sex marriage and retain that opposition here. Would effective assimilation into American society include adopting the cultural libertarianism of America’s civil religion? Or can an immigrant assimilate while still holding on to certain views that may be considered traditional? And will the second generation still hold on to those beliefs?

At Tian Fu, the second generation grapples with what it means to be a “real American” all the time. Asian Americans have long been typecast as the Orientalized other, whose existence does not map neatly onto the American racial discourse. In various Sunday school discussions I have led, the group—composed entirely of second-generation Chinese Americans—inevitably becomes a safe space for discussing personal questions of identity. Many discuss the feeling of in-betweenness that comes from being raised by immigrant parents while attending American schools, as well as the tensions of growing up in a religious household while socializing within a secular culture.

The only churches growing at a rapid clip are those that do not offer services in English.

During a group exegesis of Galatians 3:28, one student pointed out that Paul’s proclamation that there is “neither Jew nor Greek” was framing and breaking an ethnic binary in a way that resembled the Asian American in-betweenness of being neither white nor black, or neither foreign nor fully American. There were also comparisons made to concepts learned in history class, like that of W.E.B. Du Bois’s notion of double consciousness, which Du Bois framed in terms of the “spiritual strivings” of the “American Negro” in contrast to the “religion of whiteness.” The parable of the good Samaritan was held up as another example—when the beaten man was ignored by both the Jewish priest and the Levite, it was a member of a third group, a despised stranger from the foreign land of Samaria, who appeared out of nowhere and showed him who his real neighbour was.

Because the Sunday school class served as the only place where second-generation Chinese Americans were able to gather independently from other groups, the class allowed discussions of identity unencumbered by the watching eyes of one’s parents or the categories of society writ large. The need for translation, so constant in a second generation’s experience, was, at least for a moment, gone. There is huge value in creating spaces for specific diasporas living through a kind of metaphysical transition.

The order of priority when it comes to identity by faith versus ethnicity tends to shift depending on where one falls in the generational line. For instance, Korean immigrants will identify with their ethnicity first and their Christianity second, whereas second-generation Korean Americans will identify as Christian first and Korean second. The same goes for Chinese Americans, although, because the Chinese American story is so much older, there are far fewer second-generation Chinese Americans to be able to have many churches oriented around serving the specific needs of a second-generation population. As a result, many second-generation Chinese Americans either stop going to church or find a mainstream English-language church. At Tian Fu, the second generation, after heading to college, will follow one of these two paths as they find the immigrant church too antiquated and out of touch with their own spiritual and communal needs.

One second-generation college student has told me that she no longer goes to church because she does not have any time to take out of her strenuous college routine. Another student says that he does try to attend meetings at his college’s Christian club when he has the time to do so, and that Christian clubs, especially at more liberal universities, are overrepresented by international students and the children of immigrants. I am not able to fully discern if their stated reasons are their true spiritual pathways, as they may not be willing to say things to me that could paint them in a negative light to their parents. While most of the second generation speak Mandarin just fine, albeit not as well as a native speaker, they have no desire to attend services at a Mandarin-only church, as they assume that such churches not only cater to people facing a language barrier but also exist to maintain unique cultural folkways for immigrants—a path at odds with smooth assimilation.

The irony of American assimilation is real: While the idea of assimilation is associated with political conservatism, the actual process tends to make the children of immigrants more liberal, not conservative. Indeed, it is America that is secularizing while the Global South experiences regular religious revivals, and thus to assimilate into American culture is to internalize a “live and let live” ethos incompatible with the communitarianism of the old cultures that immigrant parents likely maintain.

Assimilated children often come to see their parents’ views of the world as a retrograde reminder of the “old country.” For non-immigrants, a child steeped in secular culture may merely see their conservative Christian parents’ social views as being out of touch with the ever-changing times. But the children of immigrants see the social views of their conservative Christian parents not only as anachronistic but also as an embarrassing sign of having not assimilated. After all, if America has legalized same-sex marriage, and immigrant parents still refuse to accept same-sex marriage, then for the second-generation immigrant, this means that their parents still have not adopted the values needed to fit in. A double standard emerges: native-born Americans who hold traditional or conservative views are not seen as less American for doing so, but immigrant Americans are.

Assimilation has always been the defining theme of the immigrant experience: How much of one’s ethnic culture should be preserved and passed on to the next generation, and how much should one lower oneself into the melting pot? Some immigrants bemoan that their children have completely assimilated into American culture, whereas other immigrants actively encourage their children to shed the old culture’s baggage. One Chinese mother of two American-born children told me in Mandarin that “it is good that my children won’t be like us, because it shows that they are now Americans. I came to America and worked hard so my son and my daughter can have a better life here. So why make my children conform to Chinese culture when I myself came to America? This is a free country.”

Other immigrants are more reluctant. Income plays a role: The more economically successful an immigrant is, the more the immigrant wants to assimilate to American ideals. In a sense, holding on to a non-American identity can be seen as a way for the economically unsuccessful to feel a sense of control over their lives when they cannot control their finances. Another explanation can be found in the fact that wealthier immigrants simply have more access to American culture, while poorer immigrants are stuck squatting in ethnic enclaves.

The children’s feelings toward assimilation are even more complicated, as they have no choice but to straddle the two worlds of the immigrant home and the multicultural-yet-American school every weekday. Some pooh-pooh their parents’ “backwardness” as a sign that their parents aren’t assimilating “properly,” while others feel a strange reticence that their parents not assimilate too much, as many of the children see their parents as a living, breathing connection with a culture that they are supposed to consider their “heritage.” In an era when prestigious institutions prize diversity and inclusion, entry and assimilation into such spaces often entail playing up differences in ethnic and cultural background. And as seen in previous generations of Irish and Italian Catholics and Eastern European Jews, a religion can be viewed as a part of one’s ethnic background rather than as a system of beliefs. Immigrant churches are thus sometimes seen not as religious spaces but rather as places of cultural preservation. When children of immigrants attend an immigrant church, the children may feel that attending services is like being transported to a homeland they never had.

Whereas previous generations of immigrants may have Anglicized their last names on Ellis Island, converted to Protestant Christianity, and encouraged their children to be as “American” as possible, today’s generation is learning that developing a secular cosmopolitan outlook is how one becomes an assimilated American. One second-generation member of Tian Fu summed it up: “It’s kind of funny that my parents tell me that being a Christian is needed to be seen as a real American, but I only see immigrants being Christians. My white classmates are either not religious or they are Jewish, and even then they’re not [observant Jews]. My black classmates will say they’re Christian but don’t act like it, except if they’re Nigerian. It’s mostly immigrants who I actually see being religious, not just Christian but Buddhist, Muslim, Hindu.”

It becomes crucial for immigrant Christians to ensure that Christianity does not only exist within an immigrant context. Many immigrants live in liberal cities where the native-born population is quite secular while the most religious people tend to be immigrants. In order for their children to not see Christianity as a relic of immigration and failure to assimilate, there need to be churches that are free from specific cultural or ethnic ties—churches that include non-immigrants.

You can see this immigrant-versus-second-generation dynamic playing itself out in Indian American churches. These churches tend to be filled with immigrants from Kerala (a state where Christians make up about a fifth of the population) and are part of the Eastern Reformed Mar Thoma denomination. As Prema Kurien, a professor of sociology at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs of Syracuse University, points out,

We are seeing a pattern in fault lines. The first generation, even if assimilationist in practice, will still retain those ethnic elements that distinguish it from Christianity at large via ethnic-specific styles of worship that sometimes fuse folk religions with Christianity, creating a syncretic religion that many of the second generation do not consider to be authentic Christianity. To assimilate well into American society, the second generation needs Christian practices to be decoupled from traditional Indian practices. But because the immigrants’ perceptions of Christianity are intimately tied to their ethnic identity, such a demand from the second generation proves impossible, which causes the second generation to leave the immigrant church for a church free of the cultural baggage that comes with being in a “closed” church. To become a “real American,” the second generation must find a nondenominational, cosmopolitan, and multiethnic church.

Because Indian and Chinese American Christians are not sizable enough in number to form second-generation churches, they end up finding churches with no distinct cultural heritage. Only for heavily Christian ethnic groups with a burgeoning second-generation population, like Korean Americans, can there exist independent Korean American churches specifically for those who are not immigrants.

Back at Tian Fu, the situation looks sunny. As more immigrants come to America, especially to New York City, the church’s ranks have swelled to the point where new services are needed to accommodate them all. As more Chinese Americans either immigrate as Christians or convert in America, the more likely it will be that the second generation can carry on a unique Christian tradition.

As of this moment, the situation for immigrant churches in America remains dynamic. There are too many variables, whether linguistic, cultural, geographical, theological, or otherwise, to ever paint a full picture of a prototypical immigrant church. The lack of immigrant representation at the highest echelons of American Christian discourse does not help. The most prominent immigrant contributing there, Sohrab Ahmari, has a background and conversion story that does not resemble the vast majority of immigrant Christians. Many immigrant clergy do not bother participating in mainstream discourse about the future of religion in America due to language and cultural barriers, fear of xenophobia, or simply because of a lack of knowledge or care. The immigrant, in between existence and non-existence, simply wants to survive in a new land, and figures it is not worth it to rock the boat.

Still, one thing is clear: the future of Christianity in America—and in the Western world in general—will be powered by the ever-dynamic complexity of immigrant churches, and, crucially, the willingness of the second generation to invest, organize, and reimagine these churches’ shape for a people in-between. When the Romans crucified Jesus, they thought it was over for the rabble-rousing upstart people were calling the Messiah. But just like Jesus miraculously rising from the dead, Christianity is set to defy all predictions and not only avoid death but be given new life. In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus tells his disciples to go and make disciples of all nations. In the United States, Jesus’s Great Commission is a rousing success—and it has managed to succeed in this one nation, under God.