. . . So the last will be first, and the first will be last.

In the spring of 2015 I encountered two worlds within twenty-four hours—worlds yoked by creed but divided by demographic and disposition. On a crisp Wednesday evening in May, I was invited to attend a cocktail reception at the New York Yacht Club for a celebration among Jews, Catholics, and evangelicals honouring the legacy of a man named Dietrich von Hildebrand, a philosopher and anti-Nazi hero during World War II. The room was filled with intellectuals, politicos, bankers, and think-tankers, and it was largely male and 100 percent Caucasian. These were true believers, and yet they felt isolated in their faith amid a secular elite, beleaguered as well by a mainstream culture that seemed increasingly hostile to some fundamental principles.

“New York is so secular,” one panelist lamented. “We need the moral courage of von Hildebrand to stand against the corrosive culture of our day.”

It was just weeks before the Supreme Court decision on gay marriage, and there was an air of embattled weariness in the room. The panelists sounded fearful, even defensive, though our surroundings were plush, and many of us, had you asked for a résumé summary, held pedigrees sparkling with brands like Harvard and Yale, the New York Times and Google.

Not twenty-four hours later I was sitting in the front row of Bethel Gospel Assembly Church in Harlem, waiting for graduates of Nyack College’s Alliance Theological Seminary to walk down the aisle and receive their hoods. Nyack is a Christian university whose campus in Battery Park draws from the hundreds of storefront churches that line the boroughs beyond Manhattan. The pews were overflowing with immigrant families, Asians, Latinos, and African Americans hailing from Queens, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and beyond, with the bulk of the international students coming from the majority world.

Joy and expectation filled the air as one by one the masters and doctors of divinity walked, danced, and bowed their way to the stole that would confer the student’s official readiness for ministry. According to the commencement bulletin, most graduates were planning to return to their home neighbourhoods to serve in churches, social agencies, schools, and counselling centres. Instead of expressing fear that a great Christian heritage was losing ground, there was compassion in their testimonies, the scent of hope anchored in humility and fervent faith. There wasn’t a dry eye in the room when one Nyack professor addressed the graduates: “You don’t have to wait in line behind other people who are more important than you to receive God’s love.” Said another, “If the world will not listen to your words, make them listen to your lives.”

I couldn’t help but let my mind wander back to the reception the night before. The contrast was striking. One room had held a concentration of the elite faithful, largely homogenous in educational and racial makeup, nostalgic and worried. Yet not one subway stop away was another room full of Christians of every tribe and tongue, radiating hope and purpose. I found my soul singing, moved by the sight of faith without fear or guile. Where was this world in the Yacht Club’s more foreboding diagnosis? Why the demographic blind spot among the “influencers” anxious for Christendom’s future?

It’s now been four years since that encounter, and we’ve since had an election that has exposed the cultural fences between coast and heartland, the “creative class” and everyone else. Elites are wringing their hands at a country they thought they understood, but don’t. Racial tensions are up. A crisis of solidarity has cracked open, running first along lines of social class, now layered if not eclipsed by race and ideological worldview. Some of the more prominent voices of the church, instead of serving as healing and unifying agents, have capitulated to the pressures of a divided land, baptizing their belligerence in the name of the common good while manifesting few of the virtues this good requires.

I’ve long been an appreciative student of Western civilization: I’ve been shaped by its ideals, I’ve worked for its institutions. But here at Nyack, in all its grittiness and prismatic perspective, the future felt closer, the Christian difference more palpable. Here were souls whose stories were rooted in exile, and yet they were living into it with hope and hospitality. I wondered if the more visible ambassadors of American Christianity, concerned for the future of Western civilization and the freedoms of the faithful, could learn something from their posture and build an alliance.

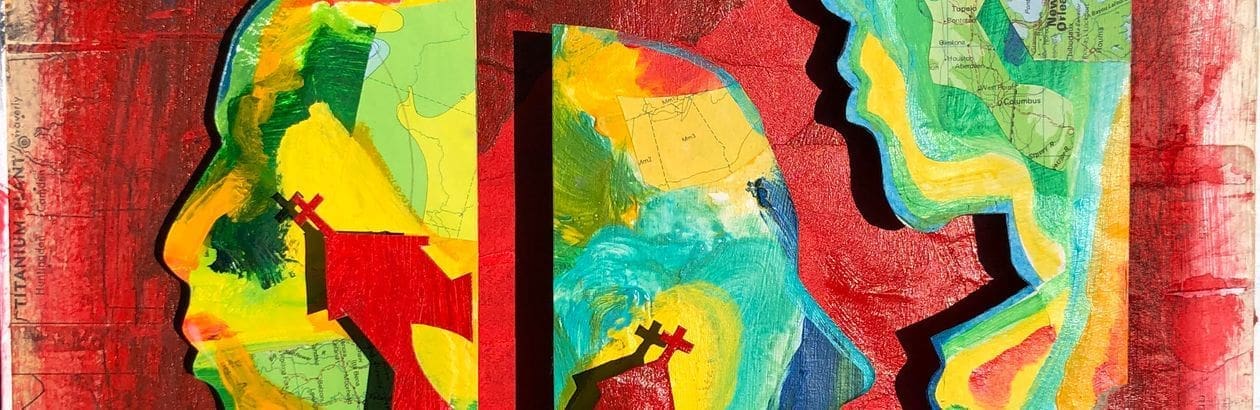

Comment magazine would like to play a role in bridging these worlds and resourcing their brotherhood. As sincere Christians navigate an era that once again scorns and misunderstands them, there is a need to look beyond each of our own cultural and ecclesial comfort zones for instruction, sustenance, and relationship. White believers in particular are expressing crisis-level concern that Christianity is threatened in the West, a fear that has driven them to make certain political choices and appear like an aggrieved minority hungry for lost power. While the freedoms of the faithful are indispensable to a thriving democracy, the rhetoric from today’s conservative spokesmen make them look amazingly ignorant of what Christianity is in their own nation, its growth and vitality among the burgeoning sectors of our society. In short, those who get to speak for “We, the church” are too often found fighting their own oppression while not attending to the struggles, energy, and the wisdom of their brothers and sisters from historically non-dominant worlds.

A subtle yet important question embedded here is one of influence: How are Christians called to influence the larger culture? In more recent years, talk of “witness” and “Christ redeeming culture” has seemed to hinge more on strategies leveraging temporal power than it has about nurturing contexts for demonstrations of God’s power. From messianic hopes placed in the White House to theories of cultural change resting predominantly on the integrity of our elites and their institutions, there seems to be a glaring forgetfulness about who Christ said he was and the Beatitudinal kingdom he came to bring.

Here is the opportunity: At a time when the loudest Christians are operating from a place of defensiveness, fear, and cultural bereavement, there is a growing source of vitality to pivot toward, learn from, and ally with—one that will create a new Christian face, a new message, a new energy, and a more rooted and inspiring faith. A compelling witness in embattled times is not going to come from legal prowess, nor from pedigreed intelligence, nor capitulation to the latest moral consensus or a mass withdrawal from mainstream culture. Instead, a compelling witness will come through humility and porousness in our more dominant faith streams to question our own assumptions and listen to our indigenous, immigrant, Asian, Latin, and African American brothers and sisters, to learn from their respective experiences as peoples of faith in the West, to learn from their cultural and civic responses, their heroes and their theological emphases. We need a Nyackized movement of doers and thinkers, across city, suburb, and agrarian community.

The Demographic Future

The world today is witnessing a non-Western explosion of Christianity. By the end of this century, Christians living in the global South and East will number 2.8 billion, roughly three times more than the 775 million projected for the global North. At the same time, migration patterns from the South to the North are leavening the spiritual tenor of a secularized West. Sixty percent of immigrants that come to the United States today identify as Christians. Latino Protestant congregations are growing while white Protestant (both evangelical and mainline) congregations are shrinking. Seventy percent of Catholic growth since 1960 is due to migration from the Philippines, Vietnam, and Latin America, with over half of this country’s Catholic young people identifying as Hispanic.

These migration patterns yield a combustible set of dynamics that involve as much theological culture clash as they birth new pathways for spiritual renaissance. As institutional Christianity continues to weaken and as the elite corridors double down on their secularist, individualistic preferences (and as the far wings of each political base do the same), newcomers bring expressions of faith that are full of vitality and without domestic baggage. The culture wars that have pitted church against world in a whiter United States don’t carry the same currency for Christians whose heritage lies elsewhere. Instead, the faith’s more experiential dimension are emphasized, as are its civic responsibilities that dwell not just on Supreme Court justice picks but also on serving as agents of compassion and hope within their local communities.

And then there is the African American church. Born in suffering and sustained despite bearing the scars of the country’s most egregious sin, I’d argue that the black church has been the leading agent of grace in American history—and yeast in Christ’s church at large. The Beatitudes certainly feel closer to the surface in black congregations, their paradoxical power embodied in a heritage oppressed but not crushed, persecuted but not abandoned. Along measures of devotion and faith practice, the American Bible Society has found that African Americans are more than twice as likely as other groups to say Bible reading is crucial to their daily routine. And indeed, while black voices were rarely woven into the evangelical unfurling of the mid-twentieth century (e.g. Billy Graham’s crusades, Young Life, InterVarsity, Campus Crusade), it is more often African Americans who draw unapologetically from Christian wells in their public engagement today. It was no aberration that President Obama sang “Amazing Grace” in mourning the massacre in Charleston back in 2015. It was no aberration that the families of the slaughtered chose to forgive the murderer who killed in the name of racial hate.

The gatekeepers of Christian thought have much to gain from expanding their circle. For one thing, many black and immigrant-dominated churches have maintained a respected civic role in a way many white evangelical churches have not. Where the latter may serve its individual members in the ways of encouragement, worship sessions, exegetical preaching, and weekly small groups, today’s black, Hispanic, Korean, and other bodies remain as much a civic pillar for their members as Americans as they are sanctuaries for prayer and worship—many of them doubling as job banks, legal agencies, homeless shelters, information hubs. In short, black and immigrant congregations more often tend to be the field hospitals Pope Francis speaks about—welcoming everyone, regardless of sin or circumstance, and caring for the needs of the whole person, not just the soul. This realism grants these local churches moral authority—not only in their home community, but in the world at large. And they offer an important lesson: If you want entrée to a hurting if skeptical world, care for it, don’t try to rule it.

Lifting Up the Shepherds

Zoom out from the reality of this century’s demographic unfurling, and you see something else. Theories of change are shifting, from top-down to bottom-up, from national to local, from institutions to networks, from structured hierarchies to open ecosystems, from advice by outside expert to praxis by indigenous shepherd. There’s a growing awareness that love can never be abstracted—we’re touched by incarnational living and doing, less prescription from on high. Macro content can paint a context within which we all think and make decisions, but it’s not determinative. It’s proximate people—and the broader moral norms and social fabric shaping how we relate to one another—that shift the terrain on which we live and make decisions.

The New America tends to understand this. In many of the seminaries attracting predominantly immigrant and African American students, the education of the Book is peopled by the education of relationship. The idea is that if you’re going to train people to be healers, you must begin with personalism. “What a wise man teaches is the smallest part of what they give,” said veterinarian Dave Jolly. “The totality of their life, of the way they go about it in the smallest details, is what gets transmitted. The message is the person.” When every faculty member gets up at Nyack’s commencement before the graduating students with a word of exhortation, you see an institution fuelled by relational genius, operating from an understanding that great and consequential human journeys only advance by parking for a spell in the blessing of spiritual mothers and fathers, active service in the community of concern, and the one on one. It’s shepherds we need to lift up, encourage, and equip, and who better than a church founded by one?

Where to From Here?

“The leaders of the future will be those who dare to claim their irrelevance in the contemporary world as a divine vocation that allows them to enter into a deep solidarity with the anguish underlying all the glitter of success, and to bring the light of Jesus there.”

So said Henri Nouwen. It’s a bracing charge for the church today. If it’s true that the top-down model of transformation has failed, how might those of us who’ve assumed that theory of influence—and thus allowed our conception of Christian witness to be infiltrated by a worldly logic of temporal power—get to a more broken place? Reflect the Beatitudes? Have the capacity to build bridges and serve from the bottom up? How do we become more of a church that remains alien to the world, yet reconciling? An alien reconciler. What might that look like?

For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. For it is written:

“I will destroy the wisdom of the wise;

the intelligence of the intelligent I will frustrate.”

Where is the wise person? Where is the teacher of the law? Where is the philosopher of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? For since in the wisdom of God the world through its wisdom did not know him, God was pleased through the foolishness of what was preached to save those who believe. . . . Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God. For the foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom, and the weakness of God is stronger than human strength.

Brothers and sisters, think of what you were when you were called. Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth. But God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly things of this world and the despised things—and the things that are not—to nullify the things that are, so that no one may boast before him. It is because of him that you are in Christ Jesus, who has become for us wisdom from God—that is, our righteousness, holiness, and redemption. Therefore, as it is written: “Let the one who boasts boast in the Lord.” (1 Corinthians 1:18–31 NIV)

The apostle Paul may have given us a roadmap. Visit a wide range of parishes around North America today, and you’ll notice that the congregations most alive are those that tend to have a lack of presumption. They’re not styled according to a particular trend or ideology, nor are they engaged in a PR scheme trying to make Christianity’s brand relevant and uncontroversial. Instead, they live in a simple yet daring expectation that God is present. They express a desire for God’s naked power, grace, and an awareness that it is in dislocation, in felt oppression, in weakness, and in persecution that the Holy Spirit often does his best work. How might those of us historically in the majority cultivate the conditions for this?

Jesus’s prayer before his betrayal in Gethsemane is as potent as it’s ever been: “that all of them may be one.” We as a cracked yet interconnected body of Protestants, Catholics, and Orthodox need the suffering streams of our church, and we need the hope-fuelled streams—not least because in Christ these realities come together. It’s not bowing to demography simply because certain numbers are shrinking and expanding. It’s bowing to demography because in the unique histories of indigenous, immigrant, and black America, the body of Christ is fully rich—and, importantly, more abjectly broken. As his was.

If Christianity is going to reclaim its collective witness in the West, an alliance must be built between elite and commoner, scholar and practitioner, black and white, able-bodied and handicapped, immigrant and indigenous, young and old. If the church is to draw closer to God’s heart and revive her force in history, she will be one of suffering, sacrifice, atonement, and humility. She will love despite fear, count the cost and consider it joy. She will be bridging, Beatitudinal, broken and bottom-up.

This is the future. This has to be the future.