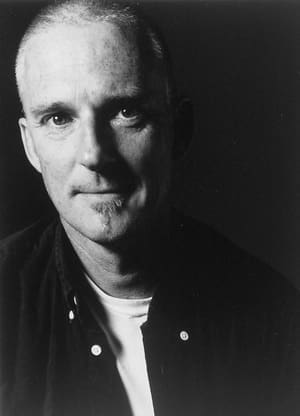

Our interview began and ended in Toronto at a local village pub, not far from where Greg lives and is so easily recognized on the street after twenty years of working in the area.

At The Sanctuary, Greg Paul guides a congregation of Torontonians who have come to trust him as pastor and friend. Our chat happened about ten months before his new book, Close Enough To Hear God Breathe, was published, which has since become winner of the 2012 Non Fiction Christian book award from the Evangelical Christian Publishers’ Association, winner of Best Book for the Word Guild Awards, and an honourable mention for the Grace Irwin Award. Jason Hildebrand and Mike Janzen are working on a full-length dramatic and musical production based on the book that will premiere in Calgary in October and Toronto in January, 2013.

Things began with a conversation about his earlier book, The Twenty Piece Shuffle.

David Peck: What really is the twenty piece shuffle?

Greg Paul: It’s a name we’ve given to a walk that folks do when they’ve got a twenty dollar piece of crack in their hand. They’re so excited it’s as if they’re high already. The actual high is always a disappointment. They smoke it and within minutes they’re down again. They’re looking for another twenty piece. It’s a great metaphor for the way those of us who are wealthier pursue our addictions to stuff or experience or whatever else it might be. We think that the next thing is going to make us happy.

David: So we all have a twenty piece shuffle of a particular sort?

Greg: Yes. Ultimately I would say that it’s about trying to find our way home. People need more than housing. They need homes—all of those things we seek that will actually fulfill us. Another word for it might be joy and in a Christian context what that means is the consummation of our relationship with our creator.

David: So do you believe the twenty piece shuffle is connected to what Pascal called “a God-shaped hole”? That we’re all, though we may not even know it, just trying to get home?

Greg: I think so. All of us are seeking something, even if we don’t know what it is we’re seeking. Somewhere we feel like we truly belong. To me, that’s home.

David: How does being home and poverty connect?

Greg: When you look at it biblically there are something like forty different terms used in the Old Testament that describe poverty. One of those categories would be destitution, which is what we normally think of as poverty—not having stuff. Another would be oppression, which is being held down and being restricted from choice by other forces. Another is affliction, and illness. For our modern world another is depression.

David: So distinctions need to be made.

Greg: People who are widows have been restricted because of loss. It’s very clear that the God of the Old Testament just like Jesus in the New cares deeply about those people. In a first-world economy those people are other. They are peripheral in our society and I think this is one of the peculiarities of first-world poverty. One of the greatest manifestations of it is exclusion from society. One of the struggles for my friends is they sit on the street corner and see thousands of people pass them in the day who belong to society at large and every person who passes them is saying to them “you don’t belong” just by their presence.

David: It’s about Dave and his first leg of the journey, as you call it. It’s about isolation and intimacy. There’s a phrase that really stuck with me from your book, “The weight of their lives, the weight of the other people” around Dave. You say that the weight was down on him, pushing him deeper into the darkness. Is that the exclusion you were referring to? Surrounded at a party and yet still feeling alone?

Greg: Exactly that.

David: You dedicate the book to the prophets of the streets, the stairwells, and the alleyways. Are they people you’ve met along the way or are they people that you have still yet to meet?

Greg: Both. The alleys and the stairwells are the places where they dwell. I call them prophets because they speak a deeper truth.

David: Raiders of the Lost Ark like?

Greg: Yeah, but of course the prophets in the Old Testament were revealing truth that had been forgotten or ignored and they were calling people back to something. I think this has certainly been true in my own life. When I get next to people who have nothing and they begin to speak to me about the realities of their lives, I begin to see a parallel between the things that I have forgotten or dismissed and haven’t wanted to face.

David: We’re back to needing each other?

Greg: Yes. What we need is difference. Difference is tremendously valuable. We say at Sanctuary that one of the markers of a healthy, welcoming community is that it’s diverse. We say this needs to be a community that welcomes everybody. Diversity is a blessing to everybody. We’re really prone to make subdivisions in our own communities. Even with people who are struggling with addictions I’ll hear alcoholics who say, “At least I’m not a crackhead.” And people who are crack addicts saying, “At least I’m not a drunk.”

David: Hierarchy and exclusion are everywhere.

Greg: Yes and it creates division. But the reality is that it’s precisely the difference between my life and the lives of my friends that calls me out of that kind of isolation. I’m a person of Christian faith and when I get close to a friend from the street who struggles with addictions and poverty and he says to me if I don’t give my life to God before I get out of bed in the morning I will die, I know that he means it. It reveals to me how little I rely on faith in my own life. I trust my own competence, my contacts, and my support network.

David: My bank account and my car.

Greg: Exactly. I trust all of this stuff and the more I have the less I am inclined to trust God and the less I am inclined to trust other people in an intimate way. As I discover the depth of my own poverty you might think there would be sadness and depression, but it’s actually joy. It’s a release from a dependence on stuff. It’s a release from that addiction. Jesus taught us that his supreme command was to love one another. What happens is that my buddy who is living under the bridge discovers that his life means something to me. He discovers that he is richer than he thought. He discovers he actually has something to give.

David: It’s a principle of the modern existential movement—Nietzsche, De Beauvoir, and Heidegger. These men and women said that we can’t know ourselves without the other. To be self-aware is to be aware of and include the other. So Levinas, a French philosopher, writes about his ethics beginning in the face. As soon as you see the face of another, it says to you thou shalt not kill. It’s his first principle.

Greg: That’s what we’re trying to do at the Sanctuary. That’s the great experiment. I’ll give you an example from when I first started working in the downtown core. Years ago I discovered quickly that I could not afford to work alone where the upper echelon of working girls were. The dark part of my psyche was saying to me you could “go” with these girls and nobody would ever know. And that was contrary to what I understood and still believe is healthy sexuality. It’s a hundred and eighty degrees from what I have with my wife. The antidote was when I began to know some of those women and was able to put a name to them and talk with them—in other words, to give them a true human face—that the lust dissipated.

David: The desire to use them . . .

Greg: The willingness to use them wasn’t there anymore because now I would be hurting my friend Roxanne.

David: It seems to me this kind of principle applies across the board.

Greg: Sure. I mean how easy would it be for us to walk into a village in India and visit a family where the kids are struggling with malnutrition and pay that person two dollars for a pair of running shoes that we know would be a hundred and fifty dollars here in Canada? I mean there are three billion people in this world who live on less than two bucks a day.

David: Your new book is great, but there’s a sense in which you still need to meet the person to get to the next level.

Greg: A book is not adequate. You need to meet people. I know people who span the political spectrum in Canada who have been changed by their interactions with the homeless and the poor. It hasn’t necessarily, though, changed their political or sense of fiscal policy. I know, for instance, that people who are very conservative financially often are inclined to give more to charity. They give more because they think that’s a better answer than taxation. That’s a political conviction for them and I respect it. I may or may not agree with that—as it happens I don’t necessarily agree—but I think it’s a both/and sort of thing. We need people taking responsibility as individuals and requiring Government to be responsible. I’m not just saying that because I think it’s important to acknowledge that this is not about bashing people who are Conservative, Liberal, NDP, Green Party, Bloc Quebecois, or anything else. It’s about saying, let’s carefully think about what really matters and if we do believe, as polls often suggest, that poverty is an issue of prime importance to Canadians; if as Christians we believe that this is fundamental to the gospel that Jesus taught us, then let’s live that way. Let’s act that way. Let’s not divorce those kinds of convictions from the way that we vote or the way that we do business or the kind of church that we go to or anything else. Let’s start thinking about how we integrate those convictions into the way we live.

David: For me it’s about the conversation. It’s the dialogue and it’s about finding the connections. Last question: Are we going to be able to get away from the twenty piece shuffle? Are we ever going to really solve poverty in Canada and around the world? Is it doable?

Greg: I’m glad you keep referencing philosophers. I think that’s where we have to begin. The real philosophies that we live by are often not the philosophies we espouse, right? For instance, how many Christians do you know who espouse the philosophy that includes grace, but don’t live that way?

David: Seems to me that you just described the Western church.

Greg: So we need to ask ourselves: What are the philosophies that guide us? I think that what we need first in order to have a hope of addressing poverty in a real way is a twenty-first century reformation . . .

David: That’s not just to do with the church?

Greg: No, not just to do with the church, but let’s start there because a philosophical reformation in the 1500’s changed the world. Any kind of significant reformation doesn’t take place in a generation, but what happened there started theologically and it reformed politics, philosophy, and everything else. If you want to start with the church you’d have to say we have forgotten a part of the gospel. The evangelical church in particular believes that the gospel is about the salvation of individuals and we’ve forgotten that it’s also about the salvation of society. And if you want to expand that philosophically and politically, what I’d say is that if we are going to see a significant reduction of poverty around the world we have to reform our sense of what society is about. We have to place people who are poor and excluded at the centre of society. We need to do that in the church. We need to do that in the political structures of our cities, our Provinces, our Country. We need to do that globally.