Here we present the second part of our interview with Al Wolters in celebration of the thirtieth anniversary of his important little book, Creation Regained. While our first instalment looked at the backstory of this big little book, this segment reflects on how the book has evolved through the years and continues to speak to an increasingly postmodern, and post-Christian West, while influencing the emerging churches throughout the globalizing world in powerful ways. You might be shocked at where this book has turned up and what it still has to say to Christians in public life today.

—The Editors

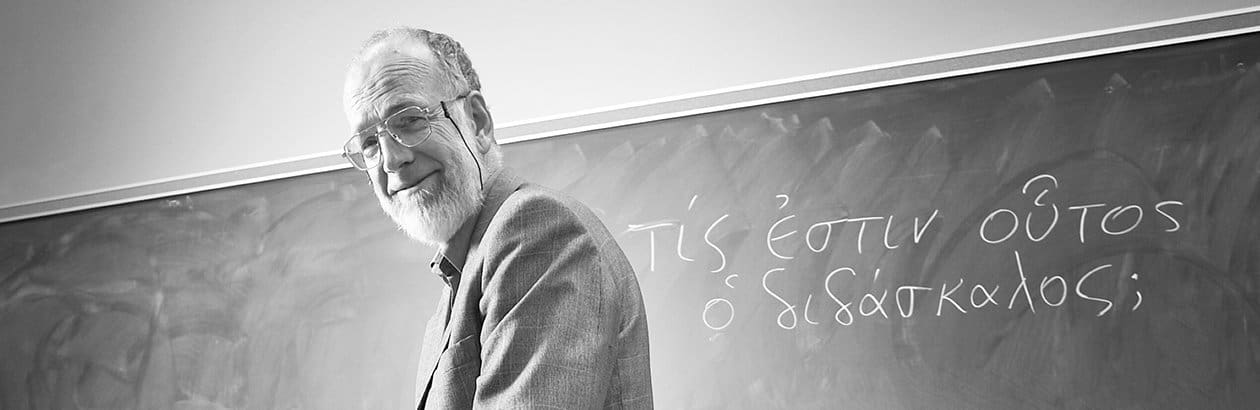

Brian Dijkema: It’s been thirty years since Creation Regained was written. What has changed? How does Creation Regained fit into the realm of ideas these days?

Al Wolters: I would say two factors are especially important. One is that, in the broader evangelical world, or, even broader than that, the orthodox world (taking that to mean every tradition that subscribes to the ecumenical creeds of the early church) there has been a decided shift toward a more comprehensive view of the Christian religion. This is in contrast to the legalism and dualism I mentioned earlier, views that used to be especially marked in the evangelical world.

There’s been an opening toward culture and scholarship among serious Christians and an impatience with the old other-worldly kind of emphasis. So in that sense, Creation Regained has ridden that wave.

But we’ve also seen in the broader culture the rise of postmodernism. One of the characteristics of postmodernism is that it stresses very much the situated nature of human knowledge. It’s against modernism; it’s against the Enlightenment project and the idea of autonomous rationality. And that’s precisely what the neo-Calvinist tradition was saying all along!

So in a certain sense you could say that the Kuyperian tradition was close to postmodernism of that thread, with the big exception that postmodernism doesn’t believe in some ultimate truth. It emphasizes that every perspective is rooted in some individual, some historical, some sociological context; and this is an important development. It stresses that all knowledge and all culture making is not neutral. They come out of some fundamental stance or some fundamental orientation which is not rational in its nature. So in that sense, to the degree that in the broader culture it has become more acceptable to stress that autonomous rationality is a myth, the perspective inherent in Creation Regained also has a greater opportunity to flourish.

Now mind you, there is also a difference between the postmodern trend in that Christianity does say there is an ultimate truth and that for all the subjectivity there is to knowledge and to culture, there is a steady Creational order. There is a God who is the same through the centuries and so on. But nonetheless, postmodernism has offered an opportunity which wasn’t there before when I was first writing. I mean, nowadays to criticize positivism is to kick open an open door. This is not new!

BD: I’ve often thought that too: that in some sense the postmodern project was simply catching up with what you were saying.

But the audience of Creation Regained has also changed. Can you tell us one or two stories about where you’ve been surprised by the places Creation Regained has travelled since it was written in 1985?

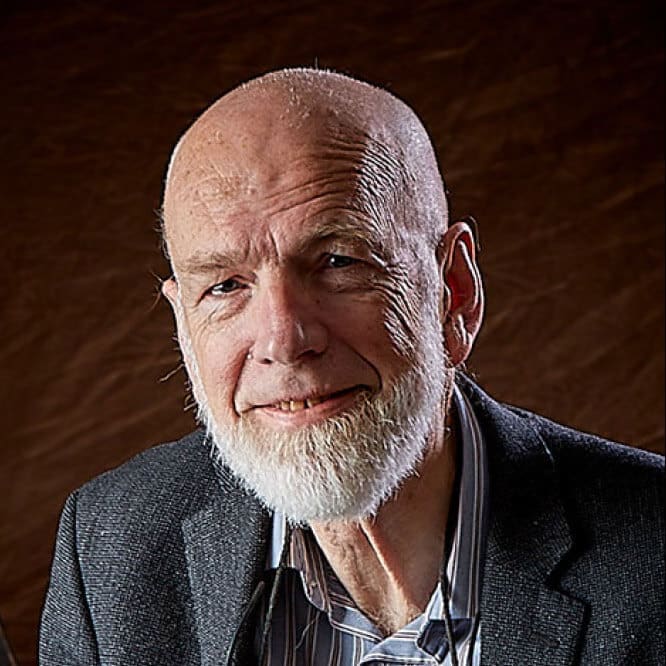

AW: Well, let me tell you an anecdote of something that happened just a year ago at Redeemer College. It was the Annual Synod of the Christian Reformed Church, which is the church that I belong to. The person being interviewed for the position of president of Calvin College, Michael Le Roy, was giving an account of his intellectual journey and how he came to a Reformed perspective. One of the things he mentioned was Creation Regained. In fact, he spotted me in the audience and waved to me. And at the same time, there was a person sitting next to me who leaned over to me and said, “I’m a missionary in Latin America and I use the Spanish version of Creation Regained for my teaching in my church.”

It was an extraordinary example for me of how both a fellow with a PhD who is now president of a college and someone who is doing very basic pioneering work in spreading the gospel in another part of the world could both use Creation Regained. Both of these connections were utterly surprising to me. And I find it utterly astonishing that Creation Regained has been translated into, I think, eleven languages now. It’s widely used in South Korea and I’m amazed that it’s had such a success in completely different cultures like Japan.

And from an evangelical perspective, I had a woman who spoke to me some years ago who told me that her brother had become a Christian through reading Creation Regained. Well, this blew me away. Especially given the fact that I wrote the book reluctantly. I was pushed to do it and if all kinds of people hadn’t ganged up on me I wouldn’t have written it.

In fact there was a time, when I had a weekly appointment with an editor who would force me to write because I was just getting my fees and not getting anything done. I didn’t even send it to a publisher myself; someone did it on my behalf. So, the whole thing has been one ongoing surprise.

Let me tell you just one more story that means a great deal to me. I have a friend who spent some years in jail and in the process became Christian. I’m still in touch with him from time to time. Well, he was watching a sermon by a South African pastor who he regularly listened to when, lo and behold, he starts talking about Creation Regained. I’m astonished by how people have adopted this kind of a broad perspective of the Gospel and by how my little book has played a part in that.

BD: To some extent it seems that the traveling of your book mirrors the traveling of the Christian religion. The changing audience of your book seems to mirror the changing face of Christianity.

While Christianity has grown in places like Africa and in Asia, Latin America and North America, the context in which the book was originally written has largely retreated from Christianity. Increasingly it seems that many here don’t so much dislike Christianity as know nothing about it.

In that context, what does Creation Regained, have to say to those facing a post-Christian cultural context? What challenges or hope does it present to us here? And how does this look like, or different than, the challenges and hopes of those reading it in a place where Christianity is suddenly becoming a majority religion?

AW: Well, that is a pretty tall order! I think the idea of pluralism is an example of something that is of great importance both in the secularizing West and in the increasingly Christianized developing countries. And I mean pluralism both in the structural and in a religious sense. In other words, both that society has a pluri-form architecture (the church is one of a number of social institutions and so on) and that religion is something that pervades all of this. And, because of this, we must respect religious differences and accommodate religious differences throughout the warp and woof of society.

I think that’s a cardinal insight that can be of use and of help to Christians in the changed circumstances of today.

And another very basic idea which I believe is part of the genius of this perspective is that life is religion. The full range of human activities are done before the face of God and that God calls us to be faithful in all these circumstances.

One other emphasis is the importance of institutions and expanded time horizons. In the West, we tend to be rather individualistic. But the idea that working institutionally over the long haul, being a salting salt in things like the banking system, or in economics, or in writing fiction requires a “long obedience in the same direction,” as Eugene Peterson says. It’s not unique to the Reformed faith, but the idea of being a salting salt institutionally over the long haul and not expecting instant solutions is, I think, another contribution of this perspective in both the old and new centers of Christian faith.

BD: Let me switch gears a bit and return to one the earlier threads of our discussion, particularly about structure and direction. Is it appropriate to say that some structures can never be directed properly? Does the framework you set up in Creation Regained make one vulnerable to any particular dangers of thought or action?

AW: I think like every other Christian tradition, [Reformed thought] has its own strengths and weaknesses. One of the weaknesses or potential dangers that has been pointed out by David VanDrunen is that this school of thought can lead to secularization. If you open up the whole world, and the kingdom of God is in all these different areas, and you get involved in all these different cultural pursuits—film making, politics, and so on—is there not the danger that you are going to simply be secularized? And, frankly, that is a danger and that needs to be acknowledged.

It is possible when you are on the rebound from a kind of dualistic perspective which emphasizes the antithesis and religious directionality to become intoxicated with the breadth of the vision of the totality of the kingdom of God and the notion that Christians have a role to play in every aspect of society. You can become so intoxicated with the idea of creation and all the goodness of creation that you lose sight of the battle between Christ and Satan, the directional antithesis between sin and salvation. You begin to minimize that.

But a danger doesn’t imply a necessity. I take it to be one of the distinctive strengths of the tradition in which I represent that it more or less equally emphasizes both the creational side and, therefore, the universal accessibility of everything in the name of Jesus Christ; but at the same time, it emphasizes the pervasive influence and the destructive effects of sin and the necessity for salvation.

But when you come from an emphasis of one side to the other, it’s very easy to lose sight of what was your strength before.

So yes, it has its dangers, but it is not unique in this regard. There is the danger to a dualistic view of the Christian life, or a “me and Jesus” personalist understanding; so there is also a danger to the idea that all of life is religion. Christians have a calling in every area of culture. We should seek to redeem—actually, I don’t like that word, redeem—we should seek to profess the claims of Christ in every area of life . We should be aware of those dangers.

But it is this way in fighting any battle. A battle is, by definition, a dangerous place! That doesn’t mean that you’re not called to fight.

BD: Can you give us some examples?

AW: Take the area of film making. I believe that there’s a Christian calling in the area of film making, but there is a very strong culture in Hollywood that makes it difficult for a Christian to retain their Christian integrity—there are enormous pressures to fit the mold that Hollywood has cast to be considered successful.

But that is not to say that, therefore, film making or the film arts are not part of God’s good grace and something that Christians ought not to be getting involved in; nor does it mean that Hollywood can’t produce films of great depth or insight. But if you want to get involved, you have to do it in a strategic way and, perhaps, in small ways, trying to be a signpost of the kingdom. It certainly means that in any of these cultural endeavors, not just in the film industry, but any others, economics as well, you can’t do things alone. You have to do it as part of a group of like-minded Christians, as part of a Christian community.

I think there are lots of examples. But the fact that there are dangers doesn’t mean that you avoid them. You simply have to approach them strategically.

BD: That ties in, to some extent, with some of the work that our editor, Jamie Smith, notes. That character is formed in community, and that communities enact certain liturgies which shape the way we act.

AW: Yes, that’s right. And it highlights the importance of the institutional church and the worship community. And that reveals another possible danger that arises out of the movement embodied in Creation Regained. If you, out of reaction to an overly ecclesial-centric perspective, begin to marginalize the role of the Christian church and say, well it’s just one sociological institution among others and on par with a chess club, or the State, or something like that, then you’re losing something central. There is something pivotal and strategically normative about the central place of the institutional church and the family.

If you lose sight of those sorts of considerations, you’re in real spiritual danger.

BD: So is there room for a variety of strategic approaches to public life which might be held within the neo-Calvinist tradition? For instance, the Benedict Option that people like Alisdair MacIntyre talk about? Might there be a time even within the neo-Calvinist tradition to say “Look, it’s time to retreat to strengthen smaller communities which can in turn strengthen the public at large”? Is that a fair reading of what you’re saying?

AW: Yes, I think so. It depends a lot on the historical situation and also what kind of differentiation of institutions has taken place. I used to say to my students that it’s not accidental that when the gospel spreads, the very first institution that gets established is the church. Very soon thereafter hospitals and schools get created, and then you end up having a Christian political presence and so on. But if there is a resurgence of Paganism, or some other religion, and Christianity again has its back to the wall, then gradually, the first things that go are things like the schools, which get taken over by the government, or the hospitals, and so on. And the last thing to go is the small place where Christians meet together for their worship service.

If you’re living in Stalinist Russia, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to start talking about the task of Christians in politics apart from praying and protesting. In a differentiated society, in a democracy, this situation is quite different. And that’s where it’s important to press hard the claims of Christ in areas like education and politics as well.

There are places where the only thing you can do is pray. Right? You may have an individual locked up in North Korea. If you’re lucky, you’re not killed and you end up in a labour camp. All you can do is pray and hope. All these grandiose visions of cultural transformation are, if you like, pie in the sky in that context. But that doesn’t mean that in the grand scheme of things this isn’t part of Christ’s plan.

Increasingly the process of secularization in North America and Europe is accelerating. I’m now 70 years old, but there has been a huge difference just in the last number of decades in Canada alone. There is a huge shift. Fortunately, there is a countervailing shift in other parts of the world, in Asia and Africa, where Christianity is spreading. But again, Islam is spreading as well.

The idea of religion somehow not being a significant factor in culture is certainly not the case in other parts of the world. To some degree, unless things change—and there are indications of change and who knows what the future may bring—there are trends which would suggest that our backs are being pushed against a wall, even while others are increasingly open to the Christian message.

BD: In some sense, it’s a requirement to be faithful and in the context in which you find yourself.

AW: Regardless of its cultural fallout, impact or effect, ultimately, success is obedience.

BD: That’s a great note on which to end. Thank you, Professor Wolters. And again, congratulations on the anniversary of this fine book. Here’s to another thirty years!