Sometimes little books have big influence. This month marks thirty years since Al Wolters’ little book Creation Regained was published. It might not look impressive at first glance. It’s not a tome that will catch anyone’s eye on your bookshelf; in fact, it’s so small it reads more like a tract or a manifesto. And yet the book has had a tremendous reach, providing Christians across North America and around the globe with a basis for engaging in public life. For many of us here at Cardus, Creation Regained gave us our first taste for public theology.

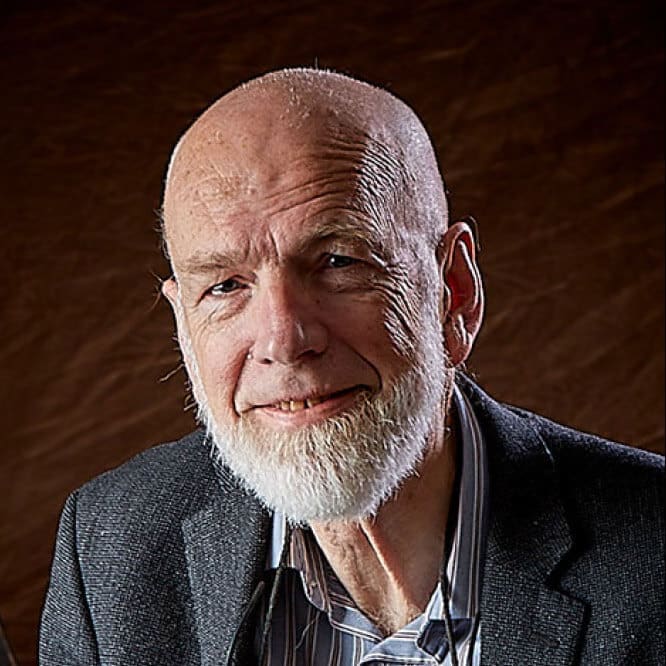

To celebrate this anniversary we sat down for a conversation with Al Wolters, who shared with us some of the story behind this important little book. We’ll feature this interview over the next couple of weeks. Then, later this summer, we’ll hear from leading Christian thinkers and practitioners from around the globe talking about how Creation Regained has shaped their work.

Take and read!

—The Editors

Brian Dijkema: 2015 marks the 30th anniversary of the publication of Creation Regained. It’s been read widely around the world, and many have described it as the best introduction to the Christian worldview. For many, in all kinds of different places around the globe, your book was the little door into a much deeper tradition of Christian thinking about culture and society. But I’m sure there are a dozen or so people who haven’t read it. How would you describe Creation Regained to somebody who’s never heard of it before?

Al Wolters: Well, it’s an introduction to a comprehensive Biblical worldview that stresses the breadth of Creation, the extent of the Fall, and most importantly, the fact that salvation in Jesus Christ really means a reclaiming, a regaining, of the entire length and breadth of Creation with all of its cultural domains.

BD: “Cultural domains” is not the kind of thing that comes up in dinner conversation, at least not in my house. What do you mean by that and what do you mean by Creation being “regained” in all of these places?

AW: Well, Creation is much broader than we tend to think of it. When we say “creation” in our culture we often speak of material things. But it also includes things like the structure of the family, for example, or something like tenderness or justice or the institutional church. Things of this sort are all structured as part of Creation.

Creation refers to those girders, those basic principles that are woven into the very fabric of civilization, of culture, of society. Therefore if you’re going to talk about sin and salvation, seeing Creation as comprehensive as that will affect how you look at the family, how you look at the state, how you look at art, and how you look at advertising. All of these things are affected by the Fall and all are in need of being reclaimed in the power of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

The book is, in a sense, a simple representation of the tradition in which I grew up—the neo-Calvinist tradition. That tradition sees Creation as a very broad and differentiated thing, filled with distinctive structures which are made to move in certain directions. Structure refers to the way things are meant to be—the way God instituted family to be, the way God meant the state to be, the way God has a design for advertising. These are all developments of Creation which are corrupted by sin and all of which need to be redirected, need to be redeemed, reclaimed in order to conform more closely to the way God meant it to be from the beginning.

That distinction between structure and direction is actually not my distinction. I learned it from my teacher Evan Runner. So structure refers to that creational substrate if you like and direction refers to the ways in which all of those different things are either perverted or are reclaimed in Christ.

BD: So for instance, something like wine, drinking wine . . .

AW: Right.

BD: Wine comes from grapes, the material, but it’s also cultural. We speak of French wine and French habits of drinking. Here in the Niagara region for instance, we have a unique climate and soil, with unique grapes. But we also have a viniculture, and certain habits around drinking. Wine can be used properly for enjoyment, for conviviality, or it can be used improperly. Is that what you’re getting at?

AW: Exactly. That’s a good example. We see how the Bible talks about wine in very positive terms: “Wine gladdens the heart of man.” Jesus drank wine on the cross. But it also has the warnings against drunkenness and abuse of alcohol beverages and so on. So that’s a very good example of how some cultural entity or some practice in itself is good and proper and creational, and at the same time can be corrupted and misused because of sinfulness. And it needs to be reclaimed. Therefore an approach with a view of creation and structure will not say one must necessarily abstain from all alcohol, but rather that one can use it discriminatingly and in moderation.

BD: Right. I’ll admit that there was an agenda behind that example. Inquiring minds want to know: does the Wolters’ household have a wine cellar that’s paid for by royalties from the sales of Creation Regained?

AW: Well, there is a cellar, but it’s not what you think. I keep a bottle of Sherry there for Alice, my wife. I’m actually a teetotaler! But Alice enjoys a bit of Sherry every now and then in the evenings. I keep a bottle of sherry there in case she runs out and I’ll say, “Oh, I think I have one downstairs.”

BD: Fantastic. You’re living out what a properly structured marriage should look like!

AW: I hope so!

BD: Let’s return to the book. Where did it come from? What was the particular context that led you to write this little book?

AW: Well, it comes from my teaching duties at the Institute for Christian Studies (ICS) where I taught from 1974 until 1984. I was a senior member in Philosophy there and one of my duties was that I had to teach a course called Prolegomena to Philosophy. It was essentially an introduction to incoming students to the philosophical tradition of neo-Calvinism and the philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd. We had students come in from many different backgrounds. Some came from Reformed backgrounds but quite a few came from non-Reformed backgrounds, generally evangelical. Some were recent converts and so the book was a way for me to introduce them to the philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd.

I had to give the students a fairly intense introduction to the kind of ethos or the general outlook out of which that philosophy grew. The students ended up calling this introduction “boot camp.” It was a concentrated course at the end of August where I would teach the essentials of what’s now in Creation Regained. It was simply an effort to sketch the underlying world-and-life view, basic perspectives which underly the philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd and his associates. The rest of the course dealt very largely with a very technical exposition of Dooyeweerdian philosophy.

Because many of these students have no background in this kind of world view it was necessary as a bridge for them to be able to see the connection between Christian faith, the Bible, and this philosophy. And, as anyone who’s read Dooyeweerd will agree, this is not immediately evident if you open up the pages of his New Critiques of Theoretical Thought!

BD: That’s the truth.

AW: So that’s how the book arose. And, I remember this very distinctly, for many students this represented a paradigm shift. It challenged them at a very deep level. Some of them resisted it very strongly, and some left the Institute because of it. But for others, it was a transformative experience and they became enthused about this whole way of looking at things.

BD: You said some of the students weren’t familiar with this perspective. Could you tell us a little bit more about the context of Christianity at the time? Can you provide some context for where ICS or, more broadly, the Reformed tradition stood in the broader context of North American Christianity at that time?

AW: I think it’s fair to say that at that time Christianity was very much characterized by a split between mainline liberal churches on the one hand, and evangelical churches on the other, some of which were fundamentalist. The liberal wing of Christianity at that time were the ones who were engaged in matters of social justice, concern for the environment and the like, but were weak on things like basic Christian orthodoxy or their view of Scripture. On the other side, evangelicals and fundamentalists tended to be very strong in their view of the inspiration of Scripture and the essentials of the Gospel, but they tended to have a bit of a “world flight” mentality—a kind of dualism between sacred and profane.

In a way, the Reformed tradition was a way to marry a high view of scripture and an orthodox view of the gospel with the realization that it mattered for public life. For the type of students that ended up at ICS—many of them were bright students from evangelical or fundamentalist backgrounds—the tradition represented a kind of liberation where they could connect their very intentional heartfelt commitment to basic Christian faith and the Bible with these broader concerns, especially in scholarship. Many of these students were not equipped to do so by their religious background.

I think if I analyze why it is that, quite contrary to my expectations, Creation Regained became as successful as it has been is that there was a kind of a broad sea change happening in the evangelical world whereby there were all kinds of factors at work to try and undermine that dualism I mentioned earlier, that sacred/secular split.

So there was kind of a vacuum, a need for a perspective which integrated the broad world of culture with basic orthodox Christianity and that’s where Creation Regained came in.

BD: Did it ever work the other way around? Did you have liberal Christians from the liberal churches who would have been very familiar with things like social action and so on, but had lower views of Scripture and orthodoxy or creedal faith?

AW: There probably are some examples of that, but they would be very much in the minority. Generally speaking the students that ICS attracted came from conservative kinds of backgrounds. Of course, I left in ’84 and so in all these years there are probably examples of the opposite direction, but they’re few and far between.

BD: The subtitle for Creation Regained is Biblical Basics for a Reformational World View. You noted that the book brought Scripture to bear on culture. Yet it’s not immediately clear or apparent that Creation Regained is Biblical. How would you describe how Scripture informs and shapes the philosophical framework that you introduce in the book?

AW: Well, that was actually one of the basic motivations in setting up the lectures as I did. And I published the book to make precisely that connection. I wanted to show that this very sophisticated and highly elaborate philosophical system that we were teaching was not just something that dropped out of the sky or that was just elaborated by some unconnected genius. It actually was rooted in a long tradition of Christian reflection and ultimately in the Scriptures themselves. That’s why Creation Regained actually has quite a lot of exegesis in it.

For instance, I deal with particular passages in Proverbs and in Second Peter to answer objections from people who, on the one hand would say, “What’s Biblical about this?” and on the other hand, people who were familiar with ways of reading the Scriptures which were quite unhealthy and which would promote a dualistic kind of reading. For instance, those who would interpret Jesus saying “My kingdom is not of this world” to suggest that politics has nothing to do with Jesus Christ or, you know, the works of the flesh just have to do with things like sex.

So the book very intentionally and deliberately sets out to show that there was a solid Biblical basis for this philosophical tradition. It’s perhaps not accidental that I ended up in pursuing Biblical studies because I was so interested in that connection.

BD: You say that an understanding of Scripture that results in this conceptual or philosophical framework has a long tradition. It’s not something that emerged in the 1950’s in a certain part of Europe, but in fact taps into a much longer tradition.

Can you describe what you mean by that? How does a book like Creation Regained fall into 2,000 years of Christian tradition and social thinking?

AW: Well, there are a few horizons here.

The immediate and direct rooting of this perspective and the work of Creation Regained, and also the work of Cardus, is Dutch neo-Calvinism. This is a particular revival of Calvinism in the nineteenth century in in Holland, in Western Europe. But that itself is a particular manifestation, in a given historical setting, of one of the basic strands that runs right through the history of Christianity. A strand which has tried to discern a proper response to the basic question of the relationship of Creation to Redemption, or nature and grace as theologians tend to talk about it.

There are a number of basic paradigms shaping that response in the Christian tradition. One paradigm emphasizes that salvation is essentially Creation Regained. That the work of redemption is a salvaging of Creation so that it might become as God meant it to be from the beginning. And that is a line that goes right back to, well, Scripture. But it goes right back to the church fathers such as Irenaeus, Augustine, John Chrysostom, and so on; and it runs right down through the centuries in various manifestations. And the Dutch neo-Calvinist tradition is a particular manifestation of this tradition that emerged in the nineteenth century within the historical context of modernism and, particularly, in the post French Revolution context which saw a significant differentiation of society.

So I see myself and the tradition in which I stand as being simply a continuation of that very long tradition going right back to the apostolic days and having all kinds of major representatives. Another one is Tyndale, the English Bible translator in the sixteenth century, and the reformer John Calvin, of course. It’s a steady tradition alongside other traditions including more dualistic ones or more world flight ones. So it’s a Catholic tradition in that sense, not in a necessarily Roman Catholic way, but of the broadly Christendom-oriented sense.

BD: Can we return to your personal development from a philosopher to a biblical scholar? You have a PhD in Philosophy from the Free University in Amsterdam which comes out of the Kuyperian tradition and was in fact started by Abraham Kuyper. But Al Wolters, professor emeritus of Religion and Theology at Redeemer University College, is somebody who taught Hermeneutics and Greek and other subjects dealing with Biblical studies.

Can you describe a little bit more for us how that transition occurred and what were some of the mileposts along the way?

AW: Well, in order to answer that I have to go back a bit. When I was an undergraduate, I was actually a pre-seminary student. I actually applied to Calvin College where I went to school as an agnostic. I wasn’t a believer and I became a believer during my first years at Calvin. So I actually planned to go to seminary, but then my eyes were opened to the importance of philosophy so I pursued philosophy. During all those years I had an interest on the side, an avocation, in Biblical studies.

I learned Hebrew on my own; I got Greek as part of my pre-seminary training. But I pursued this as an avocation, like a hobby. I was very interested in this for my personal Christian development and I was interested in studying the Bible for the sake of it. When I was teaching at ICS two things happened. One was, as I’ve explained, I was very concerned that I would show students how the philosophy or the general perspective they were learning actually had Biblical roots. And, on the other hand, I was studying the Bible out of my personal interest and I began to publish in Biblical Studies even though that wasn’t my proper field.

In fact, I was more successful in publishing in Biblical Studies than I was in philosophy! I mean if you look at my CV, well, there’s not a whole lot of the ten years that I was teaching philosophy to show for it. But my CV shows all kinds of publications in Biblical Studies. It was much more oriented to my gifts. I had a flair for languages. So that’s another factor which is something that was a very good fit for me.

Then there’s a third factor and that’s this: at ICS one of our big emphases was that in all the various disciplines—the special sciences—there are always foundational issues, philosophical issues that are at the root of the way you do scholarship. There were unavoidable first principles that need to be worked out in a Christian manner.

But it got a little frustrating to always work at that very high level of abstraction and not actually be dealing in a special science yourself. So it’s all very well to say that, I don’t know, sociology deals with fundamental issues of value, the origin of the universe and the relationship to the individual in the universal or what have you, but it’s another thing to actually work that out.

So one of the things that was attractive to me was to go into some field where I thought I would be able to do reasonably well and to bring into practice this ideal of allowing foundationally sensitive scholarship to be developed in a specific discipline. So that’s another big reason why I undertook the shift. And of course, another just absolutely historically contingent thing was that I was actually invited to apply for Biblical Studies although I had no credentials at the time, which was a golden opportunity. And this was how I ended up at Redeemer University College. I was beginning to publish in the area and so, against all precedent, they hired me and said, “Well, get yourself a graduate degree in Biblical Studies, and we’ll hire you in the meantime.” So that was, of course, an extraordinary opportunity, especially since I had been thinking if I had the opportunity ever to just devote myself to Biblical Studies, I’d like to do that.

The remainder of Dijkema’s interview with Al Wolters will appear in this space next week. Subscribe to the Comment email newsletter using the box below, or—even better—see what you’ve been missing by subscribing now to Comment‘s print edition.