M

Many of the ancients harboured a worry, now suppressed or forgotten, that the things we possess and the way we possess them might determine the sort of people we become. They thought ethics followed economics.

This is the assumption that animates Plato’s famous suggestion in The Republic, for example, that the guardians of his ideal city should have no private property or private dwellings, that they should not be allowed even to touch gold or silver. “If they acquire private land, houses, and money themselves,” Plato warned, “they will be household managers and farmers instead of guardians—hostile masters of the other citizens, instead of their allies.” For the guardians, love of self and love of city must be perfectly aligned, and the only way to ensure that is to arrange things so that their own material flourishing is identical to the material flourishing of the whole community.

Plato is not suggesting, note, that private property would introduce “adverse incentives” that might be too strong for the guardians to resist. He does not cast the citizens of his city as utility maximizers and then set out to align the guardians’ personal and social utility. He says, rather, that owning private property would make the guardian a different sort of person, a manager instead of a caretaker. That sort of person stands in a different moral relationship with the city and its citizens.

Plato’s intuition, though he does not argue for it, is that a manager of private wealth will always have an antagonistic relationship with others. Private property breeds violence.

This is all very different from the way we have come to think and speak about economic ethics today. We tend now to think (in economics as in all things) as knee-jerk utilitarians. We seek the greatest good for the greatest number, defined vaguely and measured statistically. We want to see median incomes rise and unemployment rates fall. We want to design a system of taxation that incentivizes productive investment and provides for necessary public spending. We want to put laws in place that protect consumers from being exploited by unscrupulous corporations. We are systems thinkers, beginning to end, and we test our systems by their outputs.

The question of personal character seems quaint and irrelevant in view of all this, and maybe even reactionary. It is a distraction from the hard work of building a just and humane economy. But for Plato, at least, the order of the city and the order of the soul are one and the same.

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus tells a story about a poor man named Lazarus who lives, apparently, on the street outside the gate of a very rich man’s house. The rich man is well dressed and well fed; Lazarus is sick and starving. Both men eventually die. The rich man finds himself in Hades being tormented, and he sees, off in the distance, that poor Lazarus is now seated comfortably with Abraham. He begs Abraham to send Lazarus with just a little water to relieve his pain, but Abraham refuses. The rich man has already received his comforts, Abraham says, and in any case the distance between them is too great. So the rich man begs instead for the members of his family who are still living: send Lazarus to warn them to change their ways so they won’t have to face the same suffering when they die. But Abraham again refuses. If they haven’t listened already to Moses and the prophets, they won’t listen to anyone. Jesus ends the story without comment.

This is one of those uncomfortable dicta that most Christians prefer to ignore. It is too stark for our taste, with its simple binaries and its frank, even calloused depiction of postmortem torture. When we discuss it at all, our first instinct is to temper Jesus’s severity. We treat it as a hyperbolic illustration of a general theme (Luke is just really bringing home the idea of an eschatological reversal, we say) or a rhetorical flourish meant to prick the conscience of the rich. We don’t see it as offering much in the way of practical guidance, nor certainly anything useful at the level of “economics.”

St. John Chrysostom delivered a series of sermons on this story in the late 380s that offer a better way of approaching it. John was at the time a young parish priest in Antioch; he had just been ordained in 386 but was already growing famous for his preaching. He was intensely interested in the particular words and images the biblical authors invoked. He wanted his hearers to linger with them, to internalize them. And so, characteristically, he devoted his entire first sermon to just two sentences:

There was a rich man who was dressed in purple and fine linen and who feasted sumptuously every day. And at his gate lay a poor man named Lazarus, covered with sores, who longed to satisfy his hunger with what fell from the rich man’s table; even the dogs would come and lick his sores.

What can we understand about the rich man from this terse description? John thinks it tells us everything we need to know. The rich man is cavalier, contemptuous, and cruel. Imagine: every single day, you walk past this poor man, gaunt and visibly ill. Every single day, you eat your fill and walk out of your house, past this man who would be sated with what had fallen to the floor while you were eating. Every single day, you dress in expensive linen and step around his exposed, sore-covered body. Every single day—even multiple times! “For the man was not lying in the street,” John says, “nor in a hidden or narrow place, but where the rich man whenever he made his entrance or exit was forced unwillingly to see him.”

What kind of person could do that? It’s clear that the rich man is not offering help to anyone else either. If he was going to help anyone, it would be this person he saw day in and day out. Maybe he had been tempted to help at first. Maybe he felt the pangs of pity. But day after day, refusing to do the least thing to help Lazarus (though the rich man would surely not have stooped so low as to ask his name), his heart would grow inevitably harder. He was repeatedly offered the opportunity to show compassion; he repeatedly refused it. And in refusing it, he became incapable of it.

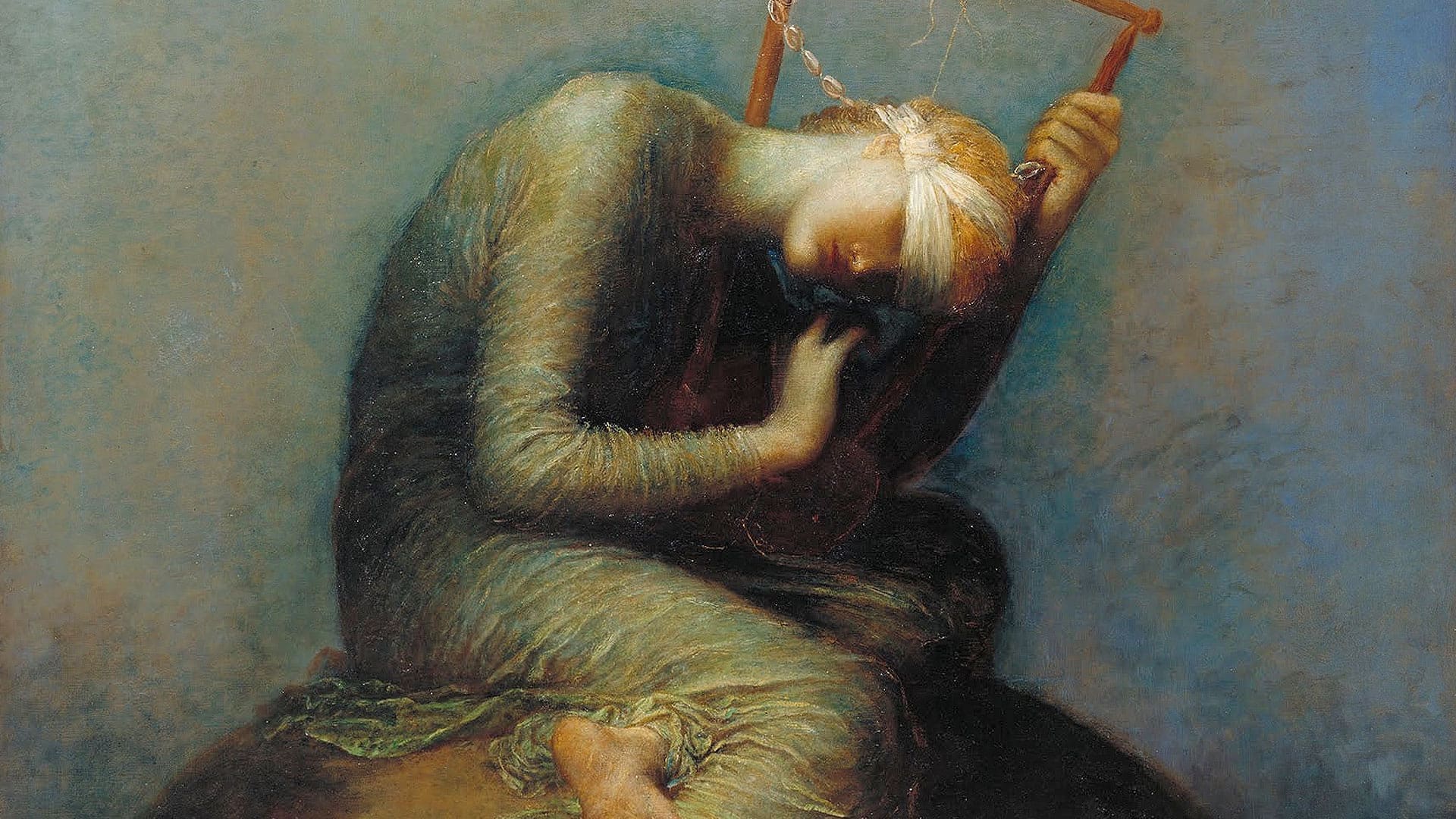

This is the rich man’s central failing: he was incapable of pity, incapable of empathy. And the capacity for empathy, John often stresses in his writing, is essential to our humanity. By closing himself off to the suffering of the poor man outside his gate, the rich man demonstrated “the worst kind of wickedness,” “an inhumanity without rival.” He became more beast than human—more beastly even than the beasts.

This is the rich man’s central failing: he was incapable of pity, incapable of empathy.

The cause of the rich man’s inhumanity, John suggests, was luxury. “Luxury often leads to forgetfulness.” The feasts and the fine robes had lulled the rich man into a kind of waking sleep, in which he was oblivious to the needs of the human being he stepped over every time he left his house. And once forgotten, Lazarus posed no obstacle to ever-greater indulgence.

So again: ethics follows economics. The man’s relationship to his possessions determines his relationship to his fellow creatures. The very fact of his indulgence in luxuries, the very fact that he is “a rich man,” sets him in a particular moral relationship with Lazarus. What might strike us as hyperbole in John’s description of the rich man—his utter heartlessness, his perfect cruelty—is not hyperbole at all, but a description of the implicit moral logic of the man’s economic situation. If you can sleep soundly in a bed made of ivory (“Alas for those who lie on beds of ivory!” says the prophet Amos), no more comfortable in itself than any other bed, it proves already that you have forgotten the suffering of those who are sleeping on the street. It proves that you care more for frivolous displays of wealth and status than for other human beings.

What John illuminates that Plato does not are the psychological devices by which this moral logic becomes a social reality. John illustrates the process of moral formation by which luxury slowly destroys our ability to recognize the concrete suffering of other human beings. There is a certain cruelty in the very idea of eating sumptuously while Lazarus starves outside your door. Over time, the cruelty takes over the rich man completely.

Neither Jesus nor John says that the rich man felt any overt ill will toward Lazarus. That is part of the point. The rich man probably did not even notice Lazarus, in the end. Even from Hades, the rich man talks to Abraham about Lazarus rather than addressing him directly. Lazarus had become for him a non-person.

In the story Jesus tells, Lazarus has a name and the rich man remains nameless. Augustine mentions this detail in one of his sermons: “One man’s name was bandied about, and God kept quiet about it; the other’s name was lost in silence, and God spoke it.” The non-person is a person to God.

John would have been happy, no doubt, for all his listeners to immediately renounce their luxuries. He had lived his life as a hermit before being ordained, and continued to champion the ascetic life in his preaching. But at this moment, in this sermon, he does not make that appeal. He prefers to work on the core problem: the failure of empathy, and the disappearance of the poor that follows on from that failure. He wants to transform the moral relationship between the rich and the poor.

He prefers to work on the core problem: the failure of empathy, and the disappearance of the poor that follows on from that failure.

So in the second half of his sermon, John leads a kind of impromptu congregational workshop in empathy. He asks his listeners to sit with Lazarus and to tarry with his suffering.

Lazarus is poor and sick. Jesus says that much explicitly. Lazarus is so poor, in fact, that crumbs would be a gift, and so sick that he does not even have the strength to keep stray dogs from licking his sores. But those are only the most obvious sources of his suffering. As John had tried to lay bare the psychological dynamics of luxury, he does the same again now for poverty.

It is not just the bare facts of Lazarus’s poverty and illness that we ought to recognize (though these are enough to break anyone, especially in combination). It is also that Lazarus is alone and lonely. He is alone and sick and poor, moreover, in a place where he has to see, every day, the very things he lacks. We all come to understand our situation by comparing it with others, and even Lazarus might be able to achieve a certain Rousseauian contentment with his lot if he were not constantly confronted, and so mercilessly, with the possibility of good health and good fortune. Even worse, John says, “he could not observe another Lazarus.” There was no one who understood his suffering, who shared in it, who might help him bear it. And on top of all this, people undoubtedly slandered Lazarus, insinuating that he must have done something terrible or irresponsible to have ended up in this sort of situation to begin with. Then as now, John says, people always blame the poor for their suffering.

John goes on like this for several long pages, guiding his listeners into the experience of poverty and through all its complicated physical and psychological assaults. These are the things, he suggests, that the rich man never considered, could never have considered, because he had been trained by his own possessions not to notice them.

The economic ethics of the early Christians is often criticized for being long on moralisms and short on structure. The Polish Marxist Rosa Luxemburg, for example, puts the point sharply: the early Christians advocated earnestly for the rich to share their wealth with the poor, she says, but “the Christian communists took good care not to enquire into the origin of these riches.” The early Christians cared about sharing their goods, but not about the structural mechanisms by which those goods were produced; theirs was a communism of consumption and not production. For that reason, their communism “proved incapable of reforming society, of putting an end to the inequality between men and throwing down the barrier between rich and poor.”

I don’t think Luxemburg is entirely wrong. Modern political economists have thought more systematically about the order of labour and production than anyone in the ancient world, and this is very much to the good. It is good that we have learned to become systems thinkers. But Luxemburg underestimates the political weight of John’s exhortations. The ancient concern for the order of the soul is deeply political.

The ancient concern for the order of the soul is deeply political.

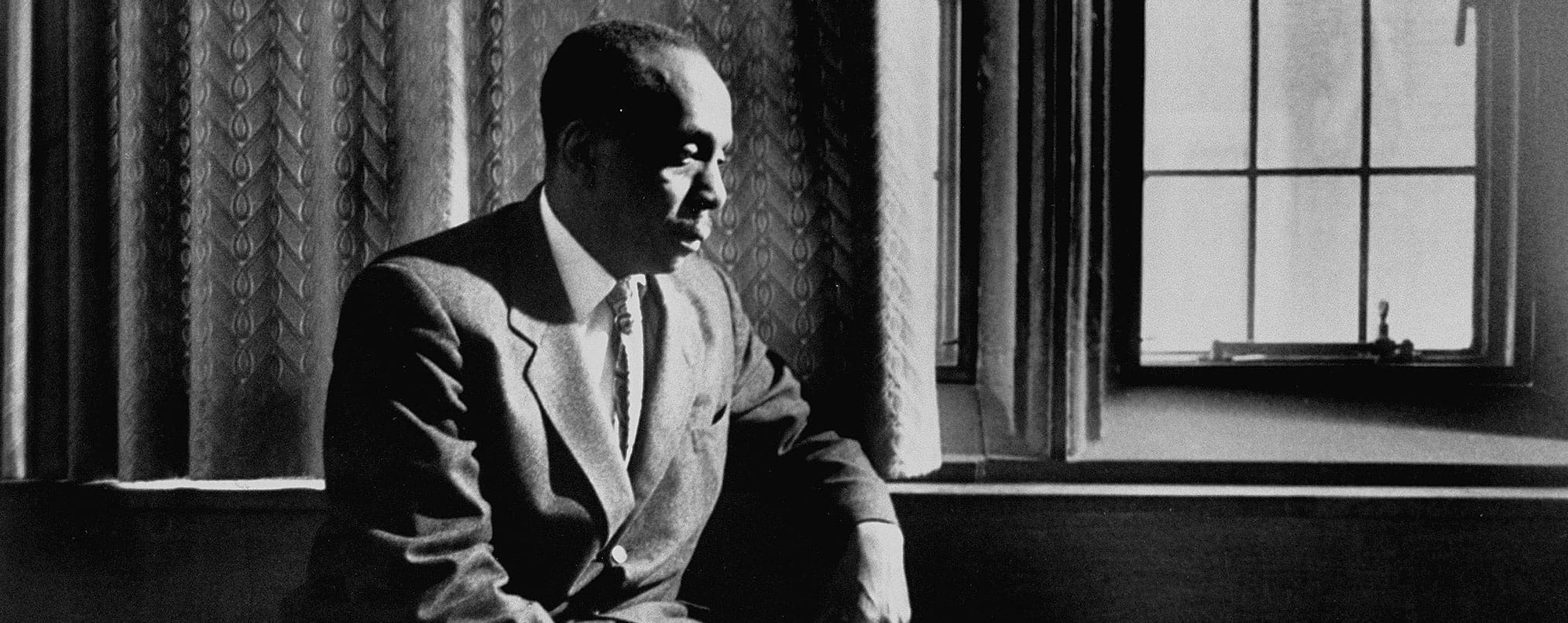

In his underappreciated classic Jesus and the Disinherited, Howard Thurman echoes the older tradition in a way that may clarify it. Writing from San Francisco in the 1940s, he was addressing racism, not poverty, but he addresses the same dynamic as John.

Oppression creates enemies, he says: it divides society into distinct groups such that the form of life of one group depends on dehumanization of the other. For a Galilean Jew in the first century, the Romans were that enemy. The social environment dictated that the presence of the Roman, especially the Roman soldier, meant the physical and spiritual erasure of the Jew. For a black person in the Jim Crow South, white people were that enemy. It was not the ill will that any particular Roman or any particular white person felt or expressed that constituted them as enemies; it was the society itself that made them so. Like Plato and John, Thurman believes that the objective architecture of our life together sets each of us in determinate moral relationships with other people. We become enemies even if we do not wish to be.

The objective architecture of our life together sets each of us in determinate moral relationships with other people. We become enemies even if we do not wish to be.

As Christians, of course, we are meant to love our enemies. In order for us to love our enemies, Thurman says, “a fundamental attack must be made on the enemy status.” That does not mean ignoring the fact that they are enemies or declaring the enemy status overcome by a moralizing force of will. It means setting out “to work on the common environment,” actually creating new social and political situations in which these enemies might come to recognize one another as human beings, even as children of God. Since segregation, Thurman thinks, is the essential premise of all oppressions, loving one’s enemy means attacking segregation itself.

John’s sermon on the rich man and Lazarus is in the first place an attempt to get the rich to recognize ourselves as enemies of the poor. The rich and the poor are always already enemies; the luxurious life of the rich man depends implicitly and inextricably on the denial of the humanity of Lazarus. But it is ultimately the rich man who has become less than human, stripped by his own oblivious merrymaking of his ability to recognize the suffering of another. John’s meditation on the suffering of the poor is not just a rhetorical tactic meant to guilt the rich into giving a few more alms. The sermon is an attack on the segregation of rich and poor, a segregation already etched in their souls, and an attempt to create an environment, right there in his church, in which the rich might learn to see the poor afresh.

It is true that John does not make any policy prescriptions. But not all politics is policy. A Christian politics—a politics of confession, we might call it—begins with an honest recognition of who we are in relation to one another. We do not always get to choose who we are. Sometimes our environment sets us against one another in ways we don’t like, perhaps in ways we don’t even grasp. But we are formed by those antagonisms nonetheless; we become who they set us out to be. To love our enemies, to cease being the enemies of others, we have to set to work on changing the world that makes us enemies in the first place.