David Henreckson: This past year was devastating for many institutions of higher education. Jobs were furloughed or lost. Departments shuttered. Many educators were forced to re-evaluate what is really central to our chosen vocation.

With all this impermanence, it seems a luxury to talk about “moral character,” or the old trifecta of truth, beauty, and goodness. So, in these austere days, is there still a central place for moral formation in the university? Or is that a peripheral concern when you are living in survival mode?

Michael Lamb: The set of crises that we’ve faced—a global pandemic, increasing awareness of racial injustice, economic uncertainty, and extreme political polarization—has certainly unsettled our institutions and created challenges none of us could have imagined. But from my perspective, it has only revealed the vital importance of character. Across various communities, we have seen the harmful and sometimes fatal consequences of decisions, policies, and structures that do not reflect core virtues of character: justice, empathy, humility, hope, courage, and compassion. If colleges and universities are to train leaders and citizens to respond well to such crises, we have to give them opportunities to develop the virtues they need to both survive and thrive.

It’s tempting when thinking in abstraction to dismiss character as a luxury, especially in times of crisis. But character is fundamental to how we respond properly to scarcity, injustice, and threats to our community, and it is especially important in helping us maintain constancy in the face of contingencies, ensuring that we stay true to our guiding values and purposes when outside events or pressures tempt us to abandon what we hold most dear. We need resilience, for example, to persist in the face of difficulty and courage to do what is right, especially when it requires great sacrifice. We need justice to give others what they are due, particularly when so many of our fellow citizens have been denied it. We need empathy to understand those who are different from us and compassion to attend well to those in need. We need humility to recognize the limits of our perspectives and practical wisdom to apply the lessons of history and experience to make good decisions in the context of uncertainty. And we need hope to resist temptations toward despair and do the hard work necessary to get through times of crisis.

DH: Character amid the ruins, then? Perhaps that sounds too alarmist, but what you said about the need for moral formation in uncertain times rings true for me. This past semester, as my students read the Stoics on contingency or the Confucians on chaos or James Baldwin on the fragility of love, the old texts felt more relevant than ever.

I had one student ask me a question that stuck. I’m teaching a seminar on the virtue of empathy right now, and sometimes it feels like we’re actually learning about the limits of empathy. After class one day, my student asked me directly and simply, “Why empathy?” I hope I gave her a decent answer, but I’ve been reflecting on this ever since. In the volatile times we’re talking about, How do we choose which virtues are most needed? Should I be teaching on courage and not empathy, for instance? What specific kinds of moral formation are suitable when civil society seems to be shattering into many pieces?

ML: Your class on empathy is especially relevant for our moment. In responding to our collective crises, empathy can be a gateway to deeper understanding and social healing.

But, as you say, empathy also has limits if it is not joined with other virtues such as courage and justice. That’s why I find the ancient idea of the “interconnection” of the virtues so compelling. While particular moments might call for particular virtues, we cannot fully develop and exercise any virtue without also having others. To practice empathy well, we need the curiosity to seek to understand another’s story and the humility to inhabit that story without imposing our assumptions, values, and biases on it. And if empathy is going to be more than a feeling, we need justice, courage, creativity, and even hard work to act on our empathy in ways that can effect healing.

That’s one the lessons I find so powerfully expressed in Leslie Jamison’s essay “The Empathy Exams.” “Empathy,” she writes, “requires inquiry as much as imagination. Empathy requires knowing you know nothing. Empathy means acknowledging a horizon of context that extends perpetually beyond what you can see.” And, she adds, empathy is not simply a passive feeling, “a meteor shower of synapses firing across the brain—it’s also a choice we make: to pay attention, to extend ourselves,” even when we are immersed in our own darkness. That is the kind of empathy that seems especially needed right now.

Davey, how do you go about teaching empathy to your students? What, in your experience, has helped them make the choice “to pay attention and extend themselves”?

DH: It’s hard. That’s the short answer. My impression is that most young adults have a disposition that looks like empathy, but lacks the structure to carry any meaningful debate or difference. A few weeks ago, I asked my students whether they knew any examples of “good disagreement,” where two parties engaged in sustained, substantive, charitable argument with each other. The response: crickets.

So I began bringing some examples of my own to class, including one incisive conversation between the brilliant Cornel West, a critical race theorist and democratic socialist, and his friend Robert George, who is anything but.

Of course, as my students noticed, West and George—despite their deep political differences—do share a common faith. And some who are unimpressed by empathy, or suspicious of political friendship across deep difference, might say that West and George’s friendship is the exception that proves the rule. What do you make of the prospects for substantive empathy in such a polarized context?

ML: I think substantive empathy is possible, and your examples provide proof of that. One important function of moral exemplars is to show that certain virtues are possible to practice in a specific context. They also provide examples for us to emulate, which, research shows, is one of the best ways to develop good character.

Your choice to present examples of friendship is particularly fitting. As ancient philosophers from both Eastern and Western traditions have emphasized, friendships provide an essential context and crucible for character formation. Friends are meaningful sources of support and accountability, challenging us to be our best selves and supplying mirrors that help us see ourselves and others in new ways. And friendships with those who are different from us are especially important for expanding our moral imagination and fostering empathy, not to mention other virtues of character.

Over the last few years, colleagues from the Oxford Character Project and I have synthesized research from various fields, including philosophy, psychology, sociology, education, and even neuroscience. As we’ve done so, we’ve noticed that exemplars and friendships rise to the top as two of the most effective strategies for character development, along with habituation through practice, reflection on personal experience, dialogue about the virtues, moral reminders, and awareness of implicit biases and situational pressures. The challenge for both of us, of course, is discerning how best to integrate these strategies into a college or university context.

DH: “Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels,” and have not friends. . . . The institute I direct at Valparaiso is associated with the ideas of leadership and service, but it seems to me substantive friendship is a prerequisite to both. It provides accountability, companionship, and shared misery in dark times. There are some national political leaders whom I strongly doubt have real friends that aren’t relatives or subordinates. That’s clearly problematic.

Do you ever worry that friendship—particularly in the university context—could prove quixotic? Could the increasingly fragmented university prove as inhospitable to true friendship as our polarized system of electoral politics?

I pointed to the example of West and George earlier. Despite their political differences, they share strong loves for a variety of things: jazz, Russian literature, Catholic social teaching, and, of course, Jesus. Perhaps all these common objects of love are what permit them to hold such opposing political views in relative peace.

When you survey many pluralistic campuses, you might wonder whether common objects of love really exist. I suppose certain commonalities might be easier to identify, especially at smaller, regional or denominational schools. But how deep do those commonalities go?

Some cultural critics of higher education think that the bonds that used to hold campus communities together are now too weak to give them a discernible identity. They suggest that we need more homogeneity and like-mindedness—perhaps on religious grounds—for our institutions to survive the current crisis. So, if we want to affirm that some measure of difference is actually conducive to friendship and human flourishing (as I assume you do), how do we respond to this line of criticism?

ML: I think difference can be conducive to friendship and flourishing, so the question you raise is important for the university context. Many American colleges and universities once assumed (perhaps wrongly) a common cultural, moral, or religious inheritance. But as Julie Reuben notes, the rise of moral and religious pluralism and increased focus on “value-free” science led many colleges and universities to abandon moral education in the twentieth century out of legitimate fears that educating students within one moral tradition was not properly respectful or inclusive of diversity. As a result, many colleges and universities adopted an approach of moral neutrality, focusing instead on the pursuit of knowledge. The challenge, of course, is that neutrality itself is not neutral. It takes a substantive stance on the relationship between ethics and knowledge—namely, that they should be separate—and allows whatever values are part of the cultural mainstream to fill the vacuum. But formation is inevitable. The question is not whether universities will form their students’ character, but how. It would be better for universities to be critically aware of how they’re forming students so they can subject that formation to critical scrutiny and be more intentional about what kind of formation they offer.

Many colleges and universities adopted an approach of moral neutrality, focusing instead on the pursuit of knowledge. The challenge, of course, is that neutrality itself is not neutral.

This doesn’t mean that universities must adopt or impose one moral tradition. It’s possible to pursue moral education in a way that welcomes students, faculty, and staff from diverse moral and religious traditions, not by requiring them to check their values at the entrance to campus but by inviting them to bring their full selves to the conversation. That way, we can all learn from each other and gain a deeper understanding of our own values and commitments. Of course, to actually have that conversation, we will need to share some value or purpose in common—otherwise, we would be talking past each other, and the conversation would never get off the ground. But the shared university community and the values that bring us together in the first place—the pursuit of knowledge and truth, for example, or the desire to serve humanity—are enough to create a common space where we can forge more commonality through dialogue, debate, and friendship. Ideally, these friendships will themselves become common goods—relationships we seek to preserve even when we might differ on matters of moral or political concern.

That’s why I appreciate your allusion to Augustine’s “common objects of love.” Augustine believed that a commonwealth finds cohesion around these common objects, but he didn’t think all citizens must have the same ultimate beliefs or commitments to live together in a shared community. He acknowledged there would be diversity, difference, and vigorous disagreement about how to understand, pursue, and protect those common objects. And even if we do not share ultimate objects of love, we can at least share proximate objects of love that enable us to be part of a shared community and secure the goods necessary for our common life. The same, I believe, holds for a university. Even if faculty, staff, and students hold different ultimate values, beliefs, or commitments, we can still converge around proximate goods—such as the pursuit of knowledge or the virtues of justice, compassion, or humility—that enable us to be part of a shared conversation about how to live. Those shared goods or values may differ from university to university, and they will certainly be subject to contestation and disagreement. But a commitment to pursuing and preserving proximate goods provides enough commonality to make a shared community meaningful.

That, at least, is how we’re approaching our work in the Program for Leadership and Character at Wake Forest. Since our students come from a variety of traditions, we welcome them to bring their full human selves into the conversation. We then seek to offer guidance, resources, and a nurturing space for discernment and deepening as they explore how to live out their values and virtues in the world. And we intentionally engage ideas, texts, and exemplars from diverse traditions to illuminate different ways of embodying an ethical life and to increase their awareness, empathy, and understanding of those who may believe or live differently. Our hope is that creating a community of care that encourages students to bring their own values into the community while welcoming difference supplies the conditions for authentic engagement and personal growth. It’s not always easy, but I’ve been struck by how hungry students are for meaningful moral conversation and how open they are to doing this difficult work together.

How do you approach the questions of pluralism and commonality at Valparaiso?

DH: At Valparaiso, there’s a long-standing emphasis on the idea of vocation. I’m quite fond of this old Protestant doctrine. For Martin Luther and other early Reformers, it was important to acknowledge that God’s calling to each person may look quite different. Some are called to be ministers, others to be doctors or carpenters or caretakers. But in each case, an individual is called to excellence and—in theological terms—obedience to a higher divine calling. No single calling is intrinsically better than another; each calling must be faithfully lived out.

Luther probably would’ve hated this appropriation of his idea, but I’ve found it helpful to think about moral diversity along similar lines. As universities become more pluralistic, and our common objects of love become penultimate (as you and Augustine put it), it’s important to recognize that our mutual pursuit of truth and goodness may follow alternative tracks. It may look different, tradition to tradition, person to person. This isn’t relativism, at all. I think it’s simply the recognition that we often find ourselves chasing after what is true and good from different starting points. And with rather different sets of authority, at least initially. (This is a bigger topic for another day.) Sometimes this sets us at odds with each other. Sometimes it reveals the ways that our different traditions converge or complement each other. But the hope, I think, is this: that through respectful yet rigorous contestation, we actually get closer to the object of our mutual inquiry—the truth.

Despite all the challenges facing higher education right now, examples of this sort of dialogue and healthy disagreement keep me hopeful. Thanks to my role as an educator, I have a front-row seat to these developments on the granular level. Many of my students enter college with a mixture of inborn relativism and uncritical idealism. The university is still, to my mind, the preeminent place to transform relativists and idealists into wise, empathetic critical thinkers and doers. Watching a student transform over a semester of intensive reading and debating, let alone four years, is truly exciting to me. In times like these, I need glimmers of hope like that.

ML: Hope is critical. In a pandemic that threatens our lives, an economic crisis that threatens our livelihoods, and a social and political crisis that threatens our communities, many of us rightly feel tempted to despair. To deny that temptation, or the difficulties that prompt it, would reflect the vice of presumption more than the virtue of hope. Yet, as James Baldwin reminds us, in moments like these, we “cannot afford despair.” To give up, to give in, would be to abandon our shared future, to refuse the hard work needed to find a way through. The promise of higher education is that it offers us the resources to both see the good and seek the good, even when possibilities seem dim. Universities who embrace that challenge and responsibility surely offer grounds for hope.

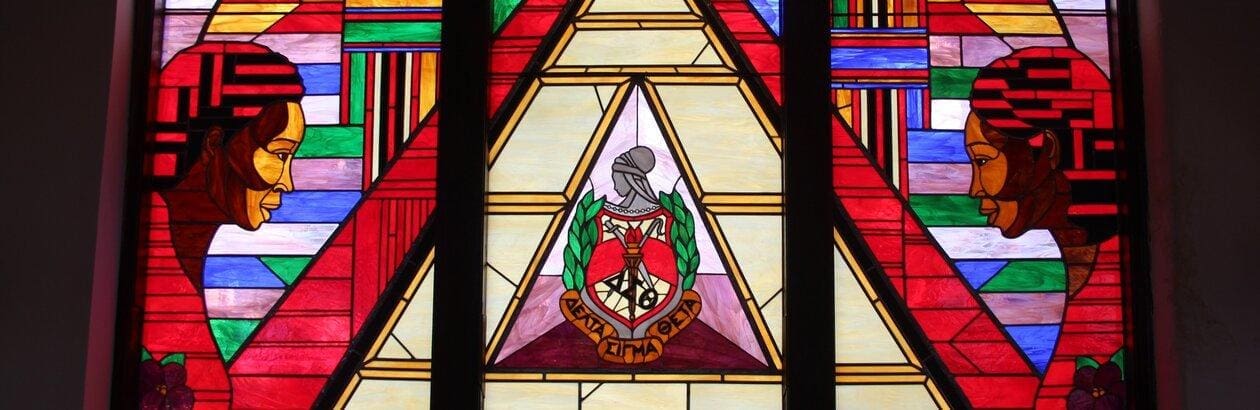

Detail from window in Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel, Howard University. Image: creativecommons/Fourandsixty