I

It was my thirty-ninth year to heaven. The wan spring sun slopes over the edge of the horizon freeing itself from the bramble of tree branches across the way from my home, illuminating the day, the sun climbing earlier and stronger, less sallow, brighter and more flagrant than the preceding days of the lately jettisoned winter. The fingers of the morning reach into the living room, pry away night, brush sleep from eyes, fuss over groggy faces. A child sits at the table scrunching cereal, eyes lolling obliquely at the back of a yellow box. Another child worries a doll’s hair with a tiny brush. The cat’s up. Where’s the food. It’s March 25, 2020, my thirty-ninth birthday, and it’s pretty much like most other days.

Wait, no. It was my fortieth year to heaven. Right? If today is my thirty-ninth birthday, that means, I guess, that, yes, today, to be precise, starts my fortieth year to heaven, even though I am just now thirty-nine. But the line’s in past tense. So it was my thirty-ninth year to heaven, and it is my fortieth year to heaven. You know what—I’m just going to scrap the Dylan Thomas reference entirely and begin again.

I

Why do we attribute significance to our sharing birthdays with celebrities or famous artists or writers or historical figures? The connection bestows on us no particular merit and provides us with no substantial connection to them. Our only commonality is the astronomical coincidence that the Earth was in the same position relative to the Sun the day we came screaming into the world flustering our fathers and mothers. But I can’t help reveling in the little historical accident that brings my life together with others. As a child, for instance, I loved the fact that I shared a birthday with Gutzon Borglum, sculptor of the Mount Rushmore memorial in South Dakota. I had briefly lived in South Dakota, and the double connection of time and place surely signified, I thought, something of import. Maybe over the years this spurious sense of connection sediments into nostalgia and eventually hardens into a riverbed of meaning we mistake for something more objective: destiny, fate, fortune.

Or maybe there’s something more to it, something a little less reductive. In the Latin of Western Christendom the term we would translate as birthday is dies natalis, literally “day of birth.” It referred, however, not to one’s biological birth but to death, particularly a saint’s entrance into eternal life in heaven, especially upon martyrdom. The day of the child’s physical birth, then, was associated with the saint on whose day he was born, and the naming of the child after the saint provided a model for the child’s life. One’s life at birth was therefore already bound up with death, which was not the end of life, but its true beginning.

In any case, I’ve always kept tucked away in my psyche the dim frisson of hope that this correlation with my historical betters, whether purely astronomical or all mixed up with history and hagiography, bestows some sort of purpose and significance to my life heretofore undiscovered.

Even if that sense of significance seems naïve now, it was natural growing up—and it had nothing to do with saints or death or martyrdom. I was at an absurdly advanced age—late high school I think—when it dawned on me with a sort of statistical clarity that I would almost surely never be famous, that my life would be utterly normal and anonymous in the same way that virtually every person who had ever lived in all of history had been utterly normal and anonymous. Maybe most people assume they’re going to be famous someday. Growing up on a steady diet of reality television and sitcoms and superhero movies, our lives have become an asymmetrical mishmash of codependency with people who bear no resemblance to us, and we don’t give a second thought to the colossal elision of context, wealth, and ambition that collapses the distance between the lifestyle of a celebrity in Hollywood and our own.

I was, moreover, born right on the Gen X–millennial cusp, and while I tend to think social analysis according to these kinds of generational trends is a bunch of baloney, I was told by teachers and by television how unlimited my potential was if I only would believe in myself. I didn’t know quite what this meant, but it sounded great. I was a go-with-the-flow kid, so I just went with the flow waiting around for all my potential to realize itself.

Whatever the cause of my misplaced assumption about my inevitable famousness, to say that the new self-knowledge of my overwhelming normality sunk in and changed me would be to overstate the case. I continued to assume that something was different and special about me, that set me apart from all my friends, and that they sensed it too. It’s taken me most of my thirty-nine years to slowly disabuse myself of the idea that I’m more than just an ordinary dude. But I have met with some success. For one thing, I’ve continued to bat away these weird assumptions that gather around my overloaded ego like gnats, and this has slowly cleared the air. For another, I am almost forty, and my potential for greatness has not yet materialized. Eventually reality sinks in.

Except on my birthday. My birthday is the day when I go up to the attic of my mind, retrieve the old childhood box of fantasies and delusions, open the dusty cardboard flaps, and take them out, if only to turn them over in my hand with an ironic, self-indulgent smile.

In my early twenties I came across a shared birthday that would exploit my latent sense of destiny but also, eventually, deepen it and transform it. Wandering around a Barnes and Noble one evening I picked up a book of Flannery O’Connor’s short stories and read, for the first time, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”—a real pick-me-upper about a family getting murdered in the woods by a serial killer. I had no idea what to make of it, but I kept reading. In the months that followed I learned that O’Connor and I shared a birthday.

II

It was my twenty-second year to heaven. In a bright white church I kneel at a rail begging Communion. A wafer is pressed into the palm of my hand, and I eat. Body of Christ bread of heaven. An elaborate chalice is held to my lips, and I drink medicinal-tasting wine. Blood of Christ cup of salvation. They are proffered by a priest with pleasant, winy breath dressed in a white alb, a brilliant green-and-gold stole, and cross-trainers. Outside the windows, thick wet snow drifts heavily to the earth and clings to waxy green holly leaves, to road signs, to eyelashes. Stumbling my way through the seasonal rhythms, I learn that my birthday almost always falls squarely in Lent—a contrast to the birthday festivities I am accustomed to. I learn, too, that my birthday is on a major feast day: the Annunciation. And according to Western practice, it is licit to break one’s Lenten fast on Sundays and major feast days. Never has church tradition come in handier. Drinks all around.

In the liturgical calendar I found a whole welter of signification for by birthday. According to Luke’s Gospel, the Feast of the Annunciation is the commemoration of the visit of the angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary, announcing to her that she would conceive and bear a son. It only stands to reason that March 25 would be the Feast of the Annunciation. It does, after all, fall nine months to the day before Christmas.

The crucifixion of Christ, it turns out, is also held to have taken place on March 25, which can’t actually be all that far off historically, given the correlation of the events of Christ’s passion with the yearly Passover celebration he was in the midst of celebrating when he was betrayed.

Going back further—way further—to the very creation of the world, it is said that the Lord God spoke the world into existence on none other than March 25. In fact, throughout much of medieval Christendom, the New Year was observed on March 25 for this very reason, and to correlate it with the Annunciation. Alas, in 1582 Pope Gregory XIII spruced up the old Julian calendar, making a few much-needed adjustments and in the process moving the New Year back to January 1. Protestants, particularly in the British Isles, loath to take any cues calendrical or otherwise from the pope, held on to the March 25 New Year till 1752, when they adopted the Gregorian calendar by authority of an act of Parliament. Even in the American colonies until this time, the New Year was celebrated on my birthday.

The coincidence of all these major days on March 25 makes a certain theological sense, symbolically if not historically. Creation, re-creation, and redemption all occur in a cyclical simultaneity, all three events knit together in time by the pure act of the eternal God. The world is created ex nihilo as the gratuitous overflow of the love of the Triune God; the world is re-created in the Virgin’s womb as an embryo, the God-man Jesus of Nazareth, the Messiah, the hope of Israel, who in his birth, growth, life, and death recapitulates in himself the drama of humanity itself; and the world is redeemed when the God-man, out of compassionate love for the resplendent, fractious species he has created in his own transcendent image, makes himself the fulcrum of the lever of his own just judgment, both judge and judged, the victim of death and its executioner—all of these things consequent upon the fissiparous mutability of God’s humbler creatures glancing off the keen edge of divine simplicity. All of it occurs on March 25. For my birthday I get the economy of salvation. Happy birthday to me.

Dante knew all this. It is on March 25, 1300, that he comes to himself in a dark wood and begins his journey into the afterlife. The date is, of course, appropriate, for Dante’s poem is at once about one man’s journey through the three stages of the afterlife and also about the entire economy of salvation. The world is a divine comedy; the world began on March 25; ergo the microcosmic world of the poem begins on March 25. Dante doesn’t belabor the point—piecing it together takes a little doing—but the date is nevertheless unambiguous. Earlier this year, in anticipation of the seven-hundredth anniversary of the poet’s death, the Italian government announced the establishment of Dantedì—Dante Day—which will be celebrated annually on March 25.

Tolkien also knew of the significance of the date. After Frodo’s failure of will and Gollum’s final attempted coup at the Sammath Naur, the One Ring through the workings of providence is destroyed in the fires of Mount Doom—on March 25 (Shire-reckoning)—ending the War of the Ring and ushering in, too, the end of the Third Age of Middle-earth. The date’s association with creation and re-creation, beginning and ending, loss and redemption was not lost on Tolkien, who exercised an obsessive refinement of detail in his sub-creative mythopoesis. An ardent Catholic, moreover, Tolkien had a special devotion to the Virgin Mary, and the link of March 25 with the Mother of God would have condensed the symbolic power of the day for him.

III

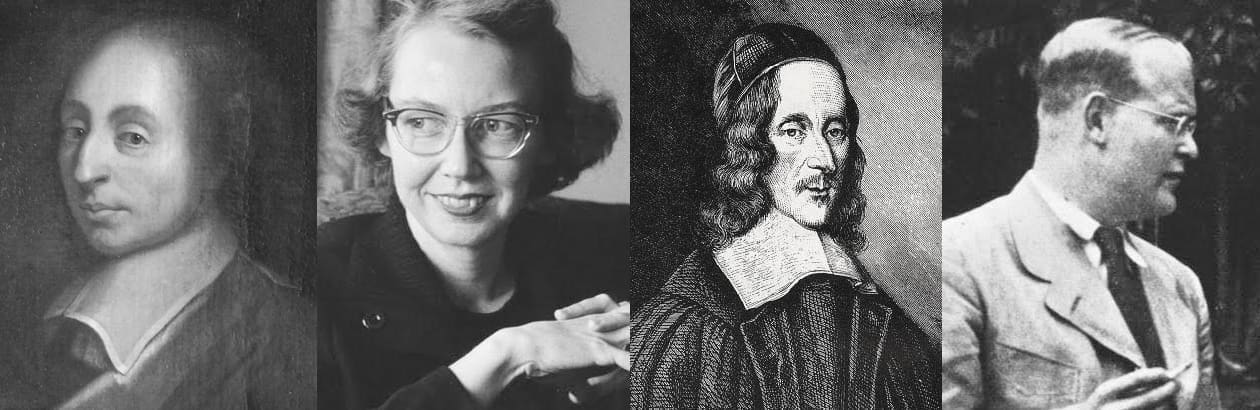

After learning that I shared a birthday with Flannery O’Connor, I noted her age at death. I’m unsure why I noted it or, then, why I remembered it. Now, on this my birthday March 25, 2020, at age thirty-nine, I am the age she was when she celebrated her last one. Then, when I was studying theology in graduate school I noticed that the Lutheran theologian and pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer died at the same age. This provokes in someone of my temper no shortage of grandiloquent meditation. So I started “collecting” writers I admire who died at age thirty-nine. My collection is not large; it has grown only to four. All four, however, share with O’Connor a body of writing that informs their death and a death that informs their body of writing.

To fulfill an elective requirement in graduate school, I took a class on faith and doubt in twentieth-century fiction, which afforded me the opportunity to dig into O’Connor’s fiction with more sustained attention than I had in college. I saw then in the macabre grotesquerie of her stories a spiritual incandescence and insight that I hadn’t understood before, and in reading her nonfiction I discovered that she had internalized and deployed a sacramental aesthetic that animated all her stories. In her letters I found a human being: wry, witty, intellectual, self-deprecating, fiercely loyal to the Catholic Church. She was also dying of lupus, and she drew meaning from her suffering without self-pity or sentimentality. Her letters reveal a soul that knew how to die well, which means she knew how to live well. Everything she wrote seems of a piece with this. The Habit of Being is an apt title for her collected letters.

Bonhoeffer was killed by the Nazis in 1943 for his participation in a plot to assassinate Hitler. By all accounts he was a gregarious and energetic person; he found spiritual rejuvenation amid the black churches in Harlem during his sojourn in the United States; he hobnobbed with the Niebuhrs; he played tunes on the piano and sang them with friends; he was a bit of a dandy. As a young theologian (and he was never anything but a young theologian) he showed incredible promise, impressing Karl Barth, who was a strong early influence, when Bonhoeffer piped up quoting Luther in one of Barth’s lectures. His thought was still developing, and rapidly, when he was killed.

Early photographs of Bonhoeffer show a cherub-cheeked World War II–era German aristocrat. If his visage weren’t famous as an anti-Nazi dissident, he would almost have the classic hammy look of a Nazi villain in an Indiana Jones film. But what all the pictures of him have in common is that they radiate potential—life, élan, ebullience. What might this life have contained? What might it have revealed? It’s tempting to wish he had been given the rest of it to live and to write, but in his death his life was revelatory. He wrote a life beyond what any book could contain.

O’Connor and Bonhoeffer were the first two I collected. Or I should say, when I learned of Bonhoeffer’s age at his death my mind immediately grouped him and O’Connor together. Their commonalities, it seemed, spoke to each other in ways I couldn’t yet fathom. Since then I’ve added two more.

When George Herbert lay dying at Bemerton, a few months shy of his fortieth birthday, he gave his friend Edmund Duncon the manuscript of The Temple: “a picture of the many spiritual conflicts that have passed betwixt God and my soul.” Almost two hundred years later, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, after remarking that most people in his day practiced their religion in a “business-like” way, said of the book, “When a man begins to be interested in detail, from hour to hour, & feels Christianity as a Life, a Growth, a Pilgrimage thro’ a hostile Country—then he will enjoy The Temple.” The stunning thing about Herbert’s poems is not that they affirm, but that they manage to affirm. His life was a slow reconciling with God. While Herbert’s poetry has over the years rightly gained the appellation devotional, it is always a devotion made precious by the price he has paid for it. It is this quality of Herbert’s poetry that continues to speak to his readers, including many who are unable to make the affirmations he is able in the end to make.

In many ways Herbert’s life is interpretable as an interconnected series of withdrawals. A private man to the end, he even requested on his deathbed that his grieving wife and nieces leave the room. He had been tacking a course away from the public world for most of his life—from a spectacular career as Cambridge orator, member of Parliament, and protégé of the great John Donne to the humble life of a country parson. The value that his poetry of devotion gave his life lay precisely in its privacy, a reversal of the role poetry played in his early career as university orator, when its purpose was the composition of verse for public occasions. The poetry Herbert wrote and refined throughout his life was at once both the substance and the precipitate of a life of contemplation. On the one hand, the poetry itself is the wrestling, not merely a record of it. But on the other hand, Herbert’s life itself would have been exactly the same had The Temple never been published. Even as he gave the manuscript to Duncon he instructed him to have it published only if “it may turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul.” Otherwise burn it, “for I and it are less than the least of God’s mercies.” At death, poetry for Herbert became life, and life poetry.

The final writer I discovered was Blaise Pascal, who famously had some sort of mystical experience in 1654, about eight years before he died:

From about half past ten in the evening until half past midnight.

Fire

God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, not of philosophers and scholars. Certainty, certainty, heartfelt, joy, peace, God of Jesus Christ.

And so on. What he wrote is not very interesting as an isolated literary document. But two pieces of information, two images, give it the resonance it has justly gained in the intervening two and a half centuries. First, Pascal sitting silent in his room caught up, for two hours, in mystical rapture. What would this have looked like empirically to the hypothetical observer? Like nothing. Like a man sitting in his chair alone in a room doing nothing. The outward form of a life often belies its inner fullness. For Pascal the fire of contemplation depended on the refusal of outward excitements undertaken to drive away boredom. Pascal sitting in his chair suffering the searing, unmediated presence of Christ is the image of mankind the deposed king back on his throne. After that experience he focused the intensity of his genius on his religious writing—the Provincial Letters and the Pensées—and he devoted himself to austere ascetical practices.

The second image: a servant, going through Pascal’s things after his death, comes across an oddity—a piece of parchment sewn into the lining of his coat. Upon examination, the parchment is found to recount the hitherto unknown mystical experience that Pascal had undergone. This was in fact the moment that Pascal’s Memorial, as it has come to be called, was discovered. He never told anybody about it. As with Herbert’s poetry, the significance of Pascal’s experience lay not in its public value but in the change it wrought in his soul. It was sewed into the lining of his coat—that’s where he kept it, always next to his heart—and he never uttered its contents to anybody.

IV

To be young is to be oblivious of death and to the possibility of death. Even children forced to confront death assimilate it into their world. Teenagers regularly flaunt it. Lying in bed reading when I was a young adult I suddenly knew for the first time—really knew in an existentially immediate way, almost felt in my body—that the body I had taken for granted my whole life would someday become inert, cease renewing itself, and die, maybe violently maybe peacefully, maybe sooner maybe later, but inevitably. Now at thirty-nine, death has become in some ways familiar to me—my parents’ mothers and fathers are now all gone—and in some ways punishingly intimate, but not a peaceful presence, not a partner with whom I have settled accounts. In their own way, each of these writers, old enough also to have been expected to negotiate death but young enough not to have been expected to reconcile with it, approached death already reconciled with it.

Pascal suffered from excruciating illnesses and ill-treatment from doctors at the end of his life. But when he became coherent just before death he received last rites and uttered a statement of humble faith: “May God never abandon me.”

On July 5, 1964, a little less than a month before she died, O’Connor wrote to a friend, “The wolf, I’m afraid, is inside the house tearing up the place. I’ve been in the hospital 50 days already this year.” But what is notable about her correspondence in the last weeks and months of her life is how unsentimental she is about her suffering—candid but matter-of-fact. Her lupine comment is as close as it gets to pathos. Perhaps she did not expect to die soon, although she had already lived several years past her prognosis and was growing weaker by the day. The spectre of death could not have been far from her bedside (it was never far from her writing desk), but it seems she cultivated an easy familiarity with it, indifference even. In any case, what she was concerned about to the very last was the revision and improvement of her art.

While indifference to death would have been unimaginable in Bonhoeffer’s situation, his last words speak not of termination but of initiation. As he was being led away to be hanged, he grabbed a fellow prisoner, a British intelligence officer, and said to him, “This is the end—for me the beginning of life.” What kind of life must precede this moment, to say these words in the face of death?

Everything Bonhoeffer meant by those words is present in Herbert’s poem “Death,” written probably near the end of his life for obvious reasons, in which he addresses the subject of the poem with what his biographer John Drury calls “good-tempered familiarity.”

Death, thou wast once an uncouth hideous thing,

Nothing but bones,

The sad effect of sadder groans:

Thy mouth was open, but thou couldst not sing.

For we considered thee as at some six

Or ten years hence,

After the loss of life and sense,

Flesh being turned to dust, and bones to sticks.

We looked on this side of thee, shooting short;

Where we did find

The shells of fledge souls left behind,

Dry dust, which sheds no tears, but may extort.

But since our Savior’s death did put some blood

Into thy face,

Thou art grown fair and full of grace,

Much in request, much sought for as a good.

For we do now behold thee gay and glad,

As at Doomsday;

When souls shall wear their new array,

And all thy bones with beauty shall be clad.

Therefore we can go die as sleep, and trust

Half that we have

Unto an honest faithful grave;

Making our pillows either down, or dust.

In an introduction to the Pensées, T. S. Eliot wrote of Pascal that he “is a man of the world among ascetics, and an ascetic among men of the world; he had the knowledge of worldliness and the passion of asceticism, and in him the two are fused into an individual whole.” This could be said equally, I believe, of O’Connor, Bonhoeffer, Herbert, or Pascal, and identifies the thread that ties them together and has tied them together in my mind over the years. Their deaths and their response to their deaths opened them out onto the world, but at a tangent—a straight line intersecting the curve of the world at the point of their suffering. In their suffering and in their genius they became transparent to both God and the world.

I began this essay with a cheeky reference to Dylan Thomas’s “Poem in October.” Reading a short biography of him, I found to my astonishment that he also died when he was thirty-nine. It’s curious how the themes pile up: his death at thirty-nine, this poem about his birthday, his preoccupation with death, particularly in “Do not go gentle into that good night.” What to make of these things?

Dylan Thomas provides an instructive counterpoint to the lives of these four, for his poetry and his death are symbolic of and inextricable from the mythology of his life, just as theirs are. But he relished and cultivated the sensationalistic persona of the hard-living poet, full of life, unpredictable and volatile. He was kind enough to complete the picture by dying in like manner, from medical complications abetted by drinking and substance abuse. The late-romantic image of the poet alone in nature contemplating on one’s birthday life and death and the passage of time, as Thomas does in “Poem in October,” in the end mixed poorly with urban twentieth-century celebrity culture. The vivid, religiously gilded nature imagery of “Poem in October,” reminiscent of Wordsworth’s emotion recollected in tranquility, nevertheless belies a narcissistic slide into solipsism. On the poet’s birthday, his thirtieth year to heaven, he is very much alone. The interior contemplation of the world is there, but it is not tempered and chastened by the ascetical, purified response to suffering. Even if one acknowledges the poignant grief in the face of death that suffuses the last stanza of “Do not go gentle into that good night,” the imperatives in the first stanza—

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

—seek not reconciliation with or acceptance of death but to overcome it by force of will. Perhaps this is a necessary counterpoint; I don’t mean to advocate a stoic submission to the tragedy of fate. But the willing acceptance with which Flannery O’Connor, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Blaise Pascal, and George Herbert approached suffering and death was not stoic indifference; rather, they found redemption not despite or even beyond suffering but in it, because they knew and hoped, and in their hope knew, that only in the willing acceptance of death is death defeated.

By the time each of these old masters reached the age of thirty-nine, they had already accomplished everything they would accomplish in their lives, save the patient instruction of their deaths. Approaching their age now, on this my thirty-ninth year to heaven, is a little like catching them up, finding myself suddenly in their company, stuttering, incoherent, hat in hand, Odysseus in Hades inquiring of the dead.