T

A gate in the wall leans open,

and you glimpse life stronger than oblivion;

at first you don’t believe your eyes—

gardeners kneel, patiently

tending the dark earth while laughing servants

cart piles of fragrant apples.

The wooden wagons rattle on thick stones,

water courses through a narrow trough,

wine returns to the pitchers,

and love comes back to the homesteads

where it once dwelled,

and silently regains its absolute

kingly power

over the earth and over me.

—Adam Zagajewski, from “Notes from a Trip to Famous Excavations”

The Sanctuary Walls

I think I cried every time. We sat on wooden pews on gently sloping floors, sanctuaried by smooth walls rising into wooden beams, our dying songs still lingering in the air. Our pastor rose from his simple chair and walked down the creaking stairs to take his place at the table in our midst. Lifting the still warm sourdough loaf—that miracle of crust and crumb—he tore it in half and held it aloft: The body of Christ, broken for you. Next the cup. We watched in silence as he removed the linen cloth from its rim, tilted an earthen pitcher over its mouth, and poured the fragrant crimson into its body. Holding it before us: The blood of Christ, shed for you. Alleluia. At that word, alleluia, each of us rose and quietly—almost sheepishly—made our way to the rounded walls of the sanctuary; none of us knowing our place, each of us knowing that a place would be found. Leaning our backs against its cool stone, we formed a circle around the room.

Taking the bread in hand, he sent one half in each direction. I watched as a little girl took the loaf in her hands, pulled a small piece for herself, and, turning, offered the loaf to the elderly man beside her: The body of Christ. And he, in turn, to the pink-haired teenager: The body of Christ. And she to the thirtysomething man with special needs: The body of Christ. And then the cup. The sipping. The turning. The offering. The blood of Christ. With each passing I felt the tears pooling in my abdomen, rising like champagne through my chest, and spilling from my eyes.

Tears are always mysterious, but looking back I see they were fed by many streams. Certainly there was shame over my sin and gratitude for the reminder that I, even I, have a place at the table. Present, too, was a deep weariness with the miseries of the world. My work in one of the poorest and most violent communities in St. Louis—even with its real beauty—left me heartbroken every week. But mostly, the tears came from a visceral encounter with the experience of hospitality; from a vision of wounded people, gathered around a table in the morning light, nourishing one another with tenderness and song. Looking back now, I see that it was these moments, so candid and unadorned, that—more than anything before or since—consecrated me into a hospitable life.

It was only natural, then, that after our graduation from seminary a few short years later, my wife and I stood before that congregation on our last Sunday among them and told of our intention to go and bear their hospitality to our new home in Virginia. At our pastor’s invitation, we rose from our pew and held hands as we walked down the aisle, past that table, up those stairs, and turned to face the people who had nurtured us. We told them of our new calling to care for students at the University of Virginia. We told them of our gratitude for their care for us and for our dependence on their ongoing love. And we told them, perhaps above all, of our commitment to continuing the life of hospitality that we had tasted among them. I remember watching my wife, twenty-six and luminous, as she stood before them—eyes shining—and said, “We want our home to have a revolving door for people who need love.”

After the service, as people stepped to gather their bags and coats, dissolving that last eucharistic ring, many of them made their way to us. They hugged us. They wished us well. They made us promise to return. A few gave gifts: a jar of homemade pickles, a slim volume of poetry, a rare coin. At the edge of the small gathering I noticed a woman—elegantly wrapped in pashmina wool—gazing at us intently. I knew and admired her greatly. She was an emblem of the sort of life to which we aspired: the meals and conversation at her table were among the most memorable of my life. We turned toward her eagerly as she approached us. Taking us both by our arms, she leaned back, fixed us in her gaze, and said, “No. Not a revolving door. Not a revolving door. Hinges and a lock.” She pulled us into a desperate embrace, released us, and walked away. I have never forgotten the look on her face. Direct and appraising, tender and compassionate, yet shadowed by lurking pain. I have also never forgotten what I felt when I beheld that look: love and kindness, but also mild rebuke and a warning whose meaning was disconcertingly beyond my reach.

The Revolving Door

A week later my wife and I stood in the dusty living room of our new home in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was a little Cape Cod—purchased sight unseen—nestled at the edges of the university. We took up the work of making it our own, a place for us and also a place for others. We began, of course, with the kitchen. Working alongside friends, we stripped linoleum, laid black and white tile, built cabinets, and installed countertops. We transformed a downstairs bedroom into a dining room, and built a deck off the back that could comfortably seat thirty people. We bought an antique bed for one guest room and made plans to add another in the basement. We painted every surface, filled every window with flowers, and hung numbers visibly on the door. And, in a gesture that will always endear me to our younger selves, we prayed for that house to be a shelter for love, and we prayed for the people—then unknown—who would enter into its warmth.

A few weeks later, they began to arrive. Students from across the country and around the world—many of them leaving their homes for the first time—came to the university to start their lives anew. We greeted them with picnics in the university gardens; with tables laden with fried chicken, baked beans, banana pudding, and sweet tea served with lime (obviously). We met them for coffee, cranberry scones passed across open philosophy books. And, in time, we welcomed them into our home.

Even now, two decades later, I think of each of them with joy: Matthew, Raine, Meg, Ruth, Will, David, Jonathan, Kelleigh, Laurie, Ramesh, Lawson, Christian, Justin, Ginny, Karen, Mike, Karver, Allison, Beth, Katie, Emily, Charles. Even now I see them—and hundreds of others—crossing our threshold and filling our home. I see them passing bowls of chips and salsa. I see them cutting limes for tea. I see them washing and drying dishes and remembering where to put them away. I see them holding our babies in their laps as we sang songs and told stories. I see them filling every space of our home under the glow of Christmas lights, bearing gifts under their arms. I see them in their best clothes—with flowers on their lapels—arriving for our annual Easter feast, many bringing platters of food they had learned to make themselves. I see them later that afternoon playing kickball in a field in the rain, a second-year named Cindy stealing home with a muddy slide and a fourth-year named Andrew falling in love with her as she did so. (I officiated their wedding two years later.) And I see them, in a bittersweet reprise of our own departure from St. Louis, walking out our door and down our sidewalk for the last time as students, bearing our love and our blessings on their heads. We had done what we set out to do. We had built a home with a revolving door.

When we left that work another five years later, we took our revolving door with us. We built a new home, imagining each room full of people and designing each doorway with enough room for multiple people to pass. We built an open kitchen, an attic apartment, a side yard with garden beds, and a front gate that seemed always to be open. When we finally moved in, we once again opened our doors, and once again people came. Easter parties in spring. Street parades in July. Costume parties in October. Family gatherings on Christmas Eve. And on every afternoon in between, children sat on our porch, friends stood in our kitchen, and neighbours picked from our garden. In time, our children joined us in the effort: harvesting beans, pouring glasses of lemonade, and decorating bowls of sugar and popcorn with flowers from the yard. Day after day, for nearly twenty years, our family lived the life of the revolving door: mornings at the market, afternoons at the stove, evenings at the table, and late nights over the sink, before falling into bed as guests slept in rooms above us.

The Shadowed Threshold

Anyone who works at hospitality long enough will tell you that this kind of life—no matter how full of light—also entails its share of shadow. There’s a reason that chefs have scars and pubs have bouncers. Hospitality, for all its beauty, is inevitably twinned with pain. And so it was for us.

Sometimes the pain was bodily. After all, the work of hospitality is just that: work. Fire and blade. Filling and emptying. Reaching in and pulling out. Scorching on and scouring off. The body bound to welcome is a body bound to ache.

Sometimes the pain was relational, caused by the (mostly) mild annoyances that come from being presumed upon. The neighbour boy who regularly plunged his muddy hands into our ice maker, filling the whole with grit. The extended (and beloved) houseguest who opened my wife’s birthday cake while she was away at work, and helped himself to the first slice. Or the older couples who, annoyed by the cancellation of our church’s midnight Christmas Eve communion service due to snow, showed up at our house at that hour with bread and wine and insisted that I serve them. In case you’re wondering, my wife stood in fuming disbelief as I—a father with four children under eight, at midnight on Christmas Eve, with hours of toys to assemble—set up a table and served them. The body of Christ. The blood of Christ. Alleluia.

But at other times, and with increasing frequency, the pain became something akin to existential. After years of cooking and cleaning, sheeting beds and doing laundry, setting up for parties and then breaking them down, welcoming guests and waving them goodbye, a deep weariness began to set in—a weariness not just of body but of heart. In retrospect, this was probably to be expected. After all, to welcome another is to share not only their plates but also their pain. It is not only to sing songs by candlelight but also to have broken-hearted conversations in the dark. Hospitality, at its heart, takes place on the shadowed threshold of sorrow. And after spending years on that threshold, often heedless of the consequences for our own selves, we began to be shadowed too. Our home, consecrated as a shelter for love, started to feel more like a prison. As my wife said, “We’ve built a life that is hospitable to everyone but ourselves.” At long last, we remembered the haunting words of our friend: “Not a revolving door. Hinges and a lock.” And we vowed to make a change.

But it was too late. For as we would discover, one of the people whom we had welcomed into our home—embraced at the door, served in the kitchen, listened to by the fire—was also a predatory abuser who, even as we welcomed him, took things from our family that could never be replaced, and poisoned the light of our home with a noxious dark.

When my wife and I learned of his abuse—perverse, violent, menacing, and repeated—and its devastating effect on our family, the shadow of that darkness engulfed us, submerging us in inky currents of bewilderment, fear, and grief. Bewilderment over what had happened—when, how, why, and what we could have done to prevent it. Fear over the terrible realization that love is always vulnerable to malice, that a life devoted to bringing light to others cannot—did not—protect us from the greed of their darkness. And grief. Endless, sickening grief. Grief that blurs the vision, takes the breath, and coils itself around every joy. For the innocent beauty that was taken. For the malignant terror bestowed.

It sickens me now. It was a form of death—not only for the members of our family, but also for the life to which our family aspired, the life we spent all of those years fashioning: the life of the revolving door. And so we removed that door and replaced it with another, heavy on its hinges. We swung it shut and barred it with every lock within reach.

Part of this closing was born of wisdom. An unfathomable shadow had entered our home. Our work—our only work—was to come to terms with its presence, understand its effects, and devote ourselves to the unbending work of exorcizing it from the hidden places of our lives. And that takes time—silent and impenetrable. But part of it was born of pain. A pain so astonishingly awful, so impervious to consolation, so scornful of light that it left us unable to do anything more than cling to one another in the shared solitude of tears. And so for nearly three years, that is what we did. We sat in silence on our couch. We cuddled in piles on our beds. We took quiet walks through our neighbourhood. We lay down and snuggled our dog on the floor. At night my wife and I checked—and rechecked—our children as they slept. And then we lay in the dark, holding hands, as the tides of sorrow broke over us again, and again, and again, and again. The doors were locked. The curtains were drawn. The guest rooms were empty. The kitchen was silent.

Across the Pass

Early one Saturday morning, in the very deepest caverns of this pain, I stood alone in my kitchen, drinking an Americano. The house was quiet—as it had been for months. A soft light fell through the window into the room. And for the first time in many months, I saw them: Copper pots, stacked on their shelves. Knives, hanging in magnetic rows on the wall. Glasses, plates, and bowls, sheltered in the cabinet. Linen napkins, folded in stacks by the window. Spatulas, spoons, and tongs gathered in an earthen pitcher by the stove. Each of these, long neglected, seemed like vestiges from a former life, like visitors from another world.

Standing there in the solitary light of that room, gazing at those tools of love, I asked myself a question that I had for months been unable to ask: Do I still believe in the life of welcome? Do I, in the face of theft, still believe in generosity? Do I, in the face of violence, still believe in embrace? Do I, in a world of predators, still believe in hospitality? And, there in the stillness of that kitchen, in the silence of that pain, my heart—to my utter astonishment—answered, Yes.

I set down my coffee, went to my study, and pulled a dusty cookbook off of the shelf. Returning to the kitchen, I slipped on my apron, opened the book, put a cutting board on the counter, set a pan on the stove, pulled down my knife, and—for the first real time in months—began to cook. I went to the market in the mornings and came home bearing gifts. I wrote recipes and taped them to the wall. I cooked in the afternoons, cleaned in the evenings, and read cookbooks late into the night.

In time, and to my family’s considerable relief, I ventured out into other kitchens. With the help of my girls, I began to cater small events in the community. I took a job working the line with Chef Tucker Yoder in Charlottesville, Virginia. Under his patient (if slightly terrifying) gaze I butchered (badly) pigs, made sauces, smoked mushrooms, picked herbs, pickled vegetables, and learned both the majesty of the Robot Coupe and the versatility of the tweezer. While there, I received that most wondrous gift of the kitchen: a nickname. At the restaurant I was—and remain—known simply as “the Blade.” In time, I began to take on early morning shifts at a local French bakery, working for a brilliant, tireless, and endlessly gracious pastry genius named Rachel DeJong. If there is a better way to watch the sun rise than standing beside a steaming oven, surrounded by the eternal mystery of yeast, I don’t know what it is.

More often than not, people from my former life—my life before the shadow fell—would come into the restaurant or the bakery and greet me with a combination of delight and curiosity: “What are you doing here?” I confess that, at the time, I didn’t really know the answer to this question, and so would mumble something about wanting to learn to cook.

But as I reflected on these conversations, I came to understand exactly what I was doing there: I was returning to the table, seeking to bear witness—even through tears—to its elemental truths. Wounded by theft, I sought the mystery of giving. Besieged by lies, I needed the clarity of oil. Submerged in ugliness, I craved the beauty of cream. Haunted by threats, my mouth longed to speak in blessing. I was there, in other words, because I wanted to bear witness to the fact that in a world in which predatory violence is so tragically real, hospitality—a life devoted to the nourishment of others—is nonetheless more real, nearer to the joyful and generous heart at the foundation of the world. And every plate sent across that pass, every sourdough boule handed steaming to outstretched hands, was for me a rosary, a silent prayer prayed by a weeping heart, not only to once again believe in that world, but also, somehow, to participate in its coming. The body of Christ. The blood of Christ. Alleluia. Though not yet ready to host again, I was ready to cook. And cooking, as the wise among us know, is nothing if not an act of hope.

Hinges and a Lock

As I write these words, my family and I still live in the wilderness of pain. Bewilderment has settled in to stay. Fear still shadows my children’s hearts. And grief still lurks in the corner of every joy. But there are signs—real signs—that this hope toward a hospitable life has taken root and is blooming out in each of us.

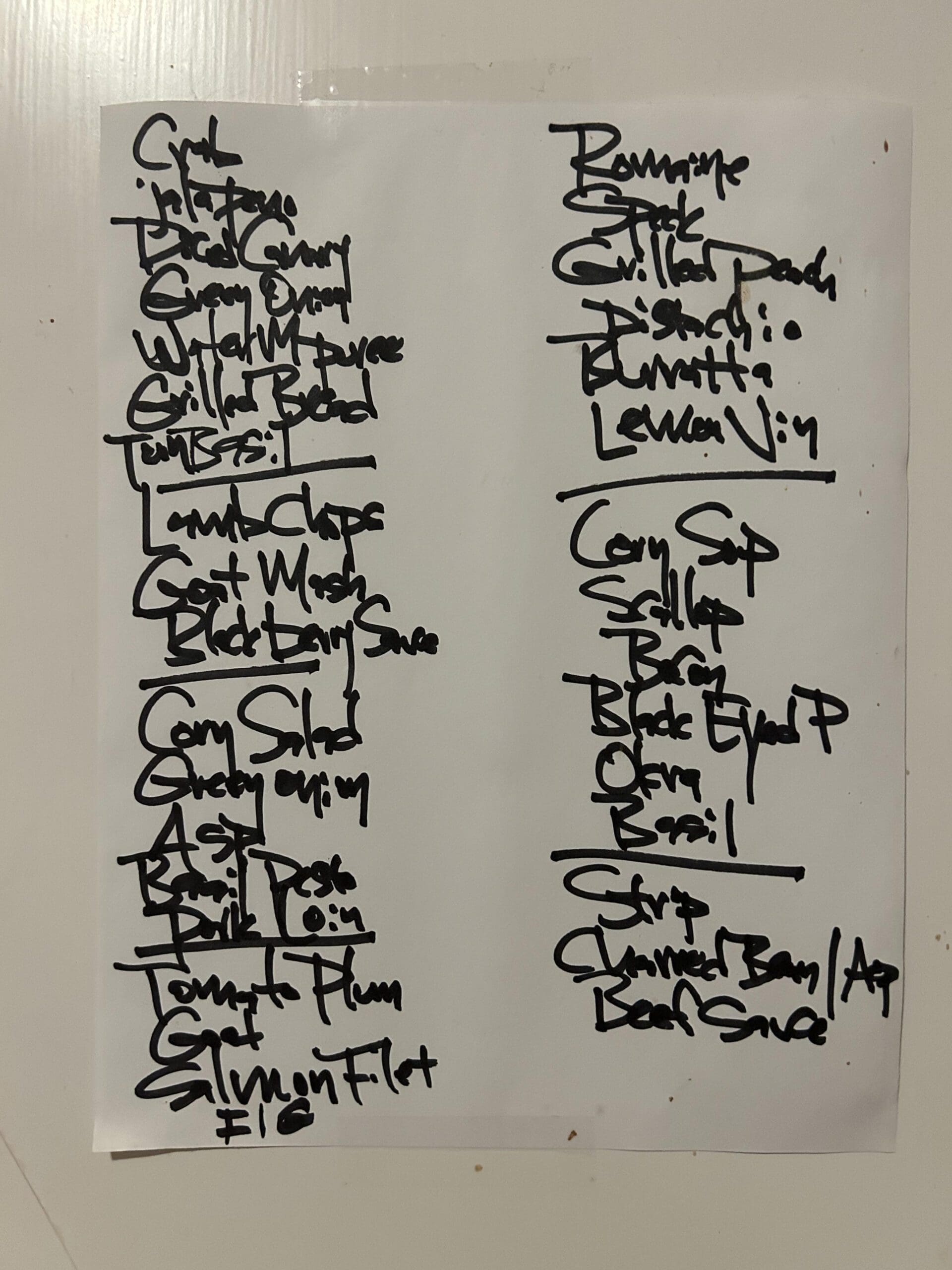

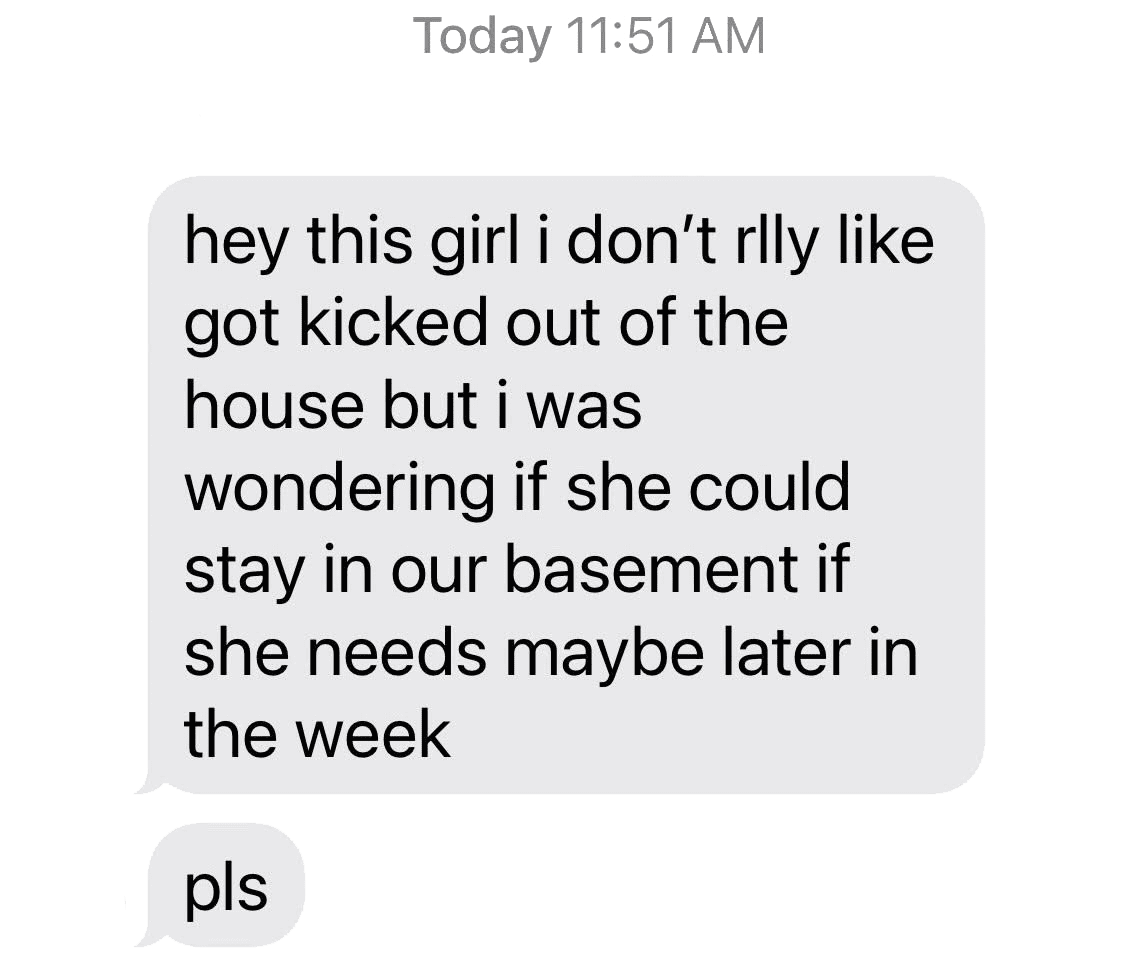

My oldest packed up one of our cast-iron skillets and took it back to college with her. My second girl is working at the bakery and has started culinary classes. Recently, my third girl texted me to ask if a schoolmate from a chaotic home—a girl, she felt compelled to add, that she doesn’t particularly like—could stay in our basement apartment. And just last night I found my youngest—a kind-hearted boy—setting up chairs around the fire pit in our yard. My wife, for her part, took a job hosting hospitality events for a local creative firm. And, perhaps most telling of all, at this very moment I can see her standing in the autumn light with contractors working through plans for the expansion of our kitchen. Each of us, in other words, has, in our own way, begun the long process of unbolting the doors of our broken hearts and opening up once again to the mystery of welcome.

These varied openings converged on a golden October weekend a few weeks back. My oldest came home for her birthday and brought her boyfriend. My second girl invited a friend to spend the night. My third, in anticipation of a homecoming dance, invited five of her friends to spend the night. And my son, as an act of desperate self-preservation, invited his best buddy over for a sleepover. Suddenly, without even realizing it was happening, my wife and I were caring for a household of thirteen. She cleaned bathrooms, dug out air mattresses, and laid out cozy pallets in rows across the bedroom floors. I inventoried our refrigerator and pantry, scrawled menus, and hurried to the grocery store. She hugged parents and children at the door and gestured toward the rooms above. I waved from the kitchen, a towel over my shoulder, and then stepped back to the stove. I cooked all weekend, starting one meal as soon as I’d cleaned up the one before. Breakfast: pumpkin brioche French toast, local sausage links, and Vietnamese coffee. Lunch: piles of flatbread, chicken and steak kebabs, homemade hummus, and fresh tzatziki sauce. Dinner: more flatbread, roast chicken, charred carrots with Baharat butter, and basmati rice with caramelized onions, dates, toasted almonds, yogurt, and parsley. It’s possible I overdid it.

On the last night of the weekend, as the kids and their friends slept in their rooms above us, my wife and I stood silently in the kitchen washing and drying dishes, and enjoying an elusive moment of quiet. Our bodies ached. Our minds whirred with the lists of things to do for the following day. Setting her towel down, she stood silently for a moment before she turned to me and said, “This feels like us. For the first time in years, this feels like us.” I nodded in knowing silence, and dried my tears on my sleeve. A few minutes later she hung up her towel and went upstairs to check on the children, opening one door after another and speaking blessing into the dark. Finally finished with the work, I hung my apron on its hook, turned off the light, and left the kitchen. Walking to the front door, I stepped outside and stared for a moment into the shadows of the night. And then, glancing toward our upstairs rooms in a gesture of prayer—please God, guard them all—I stepped inside, closed the door on its silent hinges, and turned the lock.