I

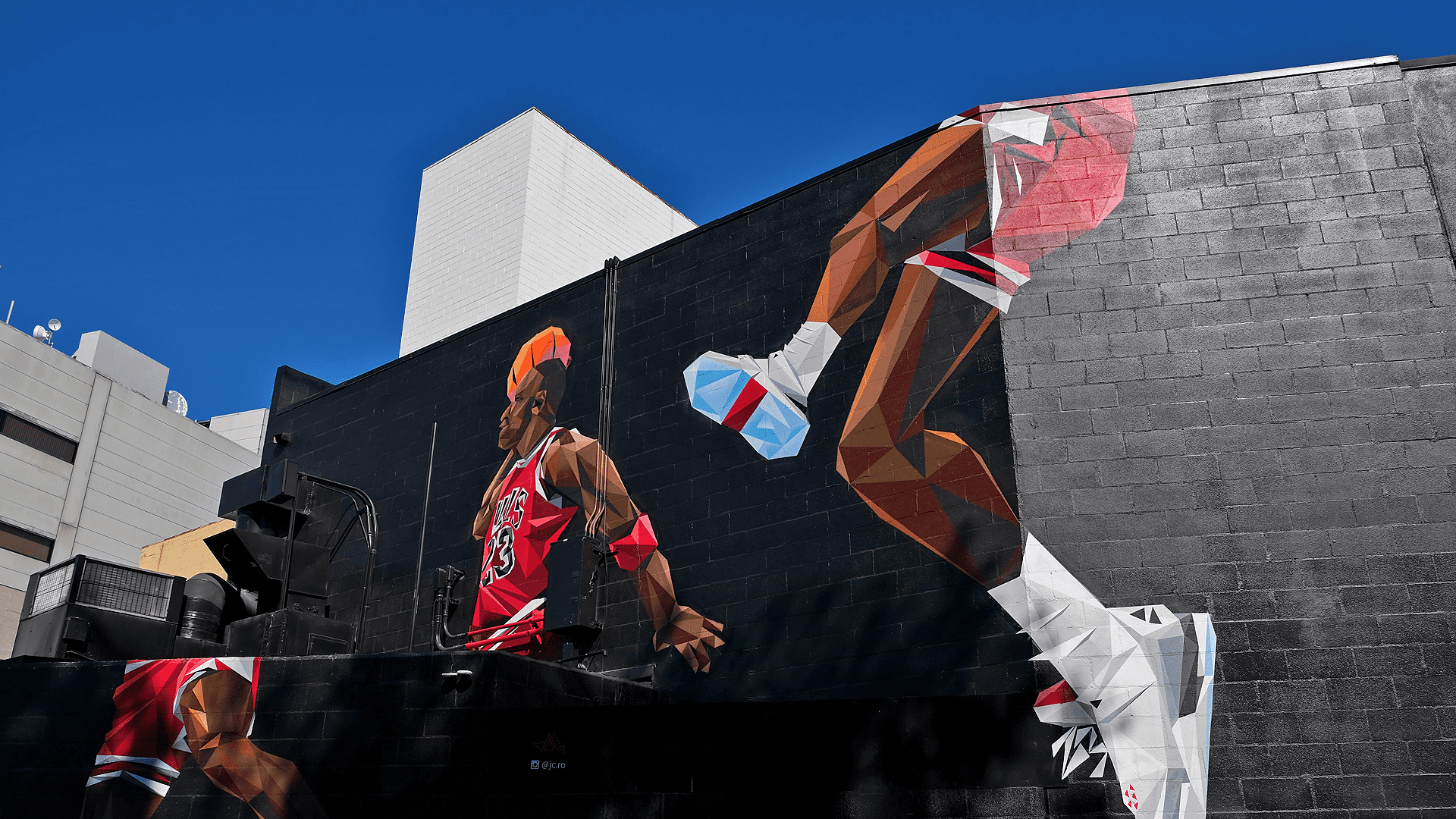

In the summer of 1990, basketball superstar Michael Jordan had an uncomfortable brush with politics. He was at the peak of his game back then, had won the first of five league MVP titles, and was a massive global celebrity beloved not only for his prowess on the court but for his character and personality too. “Be like Mike,” a slogan made famous in a Gatorade commercial starring Jordan, captured a widely held feeling.

But then he got a little tangled up in a political campaign. There was a US Senate race that year in Jordan’s home state of North Carolina. Harvey Gantt, a talented rising Democratic star who was the first black mayor of Charlotte, was running against the incumbent Republican Jesse Helms. Especially because of Helms’s racist past, the prospect of his being unseated by an African American raised the profile of the race dramatically. Reviewing its donor records, Gantt’s campaign realized that Michael Jordan had sent them a check, but without contacting them or bringing any public notice to his support. So Gantt reached out to Jordan’s mother, who was a more public supporter, asking if the star might campaign on his behalf and use his immense celebrity to help beat Helms. Mrs. Jordan took the request to her son, but he declined. And in the presence of the Chicago sportswriter Sam Smith, who later reported the exchange, he told several teammates that he didn’t want to jump into the race publicly because “Republicans buy sneakers too.”

Those words have haunted Jordan ever since, and understandably so. They suggested crass financial motives overcoming public-spiritedness, and so a kind of failure of character. Was Michael Jordan just another selfish, greedy celebrity with no broad sense of civic obligation?

When he was asked about the incident three decades later, in the fantastic 2020 ESPN documentary The Last Dance, Jordan at first dismissed his remark as a joke. But then he offered a defence of his underlying decision, and it was anything but a joke. He said,

I don’t think that statement needs to be corrected because I said it in jest on a bus with Horace Grant and Scottie Pippen. It was thrown off the cuff. My mother asked me to do a PSA for Harvey Gantt, and I said, “Look, mom, I’m not speaking out of pocket about someone that I don’t know. But I will send a contribution to support him.” Which is what I did. I do commend Muhammad Ali for standing up for what he believed in. But I never thought of myself as an activist. I thought of myself as a basketball player. I wasn’t a politician when I was playing my sport. I was focused on my craft.

“I wasn’t a politician when I was playing my sport.” Watching the documentary, this remarkable comment knocked me out of the nostalgic trance the film so masterfully induces in all red-blooded Gen-Xers, and back into our own troubled time.

That’s not quite because it justifies Jordan’s famous remark. Even as an admirer of his, not to mention a Republican who now and then buys sneakers, I still think his one-liner was boorish and shallow. Yet though he surely intended no profound commentary on American life, Jordan’s explanation of the choice he made back then actually cuts to the heart of one of the most challenging problems bedevilling our culture now. By implicitly setting a limit of the proper uses of his celebrity, Jordan asserted the possibility of meaningfully distinct spheres of human action, and of boundaries on cultural and political conflict that might make a healthier common life possible.

Such boundaries can’t be hermetic. Our lives are unified wholes, and our moral commitments must not be compartmentalized into insignificance. But those boundaries also cannot be eradicated, or else the bile of bitter partisanship will flood into the broader culture and dissolve our capacity to live with others in a vast and diverse nation.

Our lives are unified wholes, and our moral commitments must not be compartmentalized into insignificance.

Jordan’s experience three decades ago shows why the work of marking out such boundaries properly can be so difficult. But our own experience in this century should help us see why such work may be essential to the flourishing of a free society, and to the task of social renewal that now lies before us.

One Vast Combat Zone

Our culture war plainly lacks boundaries. Every realm of our lives has become one of its battlefields. Not only in politics but also in schools and universities, in corporate America, in our places of worship and places of work, in civil society and in our private lives, online and in person, there is often just no getting away from that intense, divisive, and rigidly partisan struggle.

The particular disputes over which we are supposed to be at each other’s throats constantly shift and change. Sometimes it’s race and policing, sometimes immigration and borders, sometimes American history or education, cancel culture or some bourgeoning fascism, free speech or hate speech, wokism or systemic discrimination, transgenderism, election integrity, vaccines, masks, or the latest careless proclamation of some ridiculous celebrity. The list of controversies is endless, but the parties to them are remarkably constant and durable. Individually, these fights sometimes touch on genuinely vital questions. Yet seen together they appear as a vast sociopolitical psychosis. They are all one fight, and the fight is the point. This is the sense in which we are living through a war of cultures, not of ideologies or interests. It is about us and them—competing identities, opposing teams, contending antipathies, contempt as far as the eye can see. Each party knows the other is the country’s biggest problem, and the latest outrage is just more evidence (as if we needed it).

But the sheer reach and range of the dispute may be what stands out most now. Whatever is the leading cultural controversy of the hour demands our attention and implies action in every domain of our lives, so the differences between different domains become blurred. We end up doing more or less the same thing everywhere—displaying our team colours and expressing our partisan affiliations. This quickly gets tedious. But it raises deeper problems in those domains where we have other important work to do. Displays of partisan allegiance and factional solidarity may have their place, but they do not belong in every place. And out of their place, they can displace other essential goods, and can divide us along lines that render common action and ultimately common life impossible.

Displays of partisan allegiance and factional solidarity may have their place, but they do not belong in every place.

Of course, we constantly engage in such displays out of their proper context. In our economic life, this can look like companies speaking out on a range of social and political issues well outside their expertise or reach, and in ways that make their business more divisive than it needs to be. A recent study by Brunswick Consulting found that “63% of corporate executives agree unequivocally that companies should speak out on social issues,” though only a third of American voters say the same. A company whose products or services you purchase makes it much harder for you to be a customer when they take a position you deeply disagree with on a subject you consider important—let alone when they actually use their power in the economy to advance that cultural or political agenda.

The same forces are evident in the world of work now, where employers feel pressure from some of their workers to take formal positions on prominent issues that have nothing to do with the work they’re engaged in, and do so in ways that alienate other employees or turn the workplace into another arena of combat.

Some core professions in American life are going through a similar process, identifying themselves with one side of our culture war in ways that make it hard for people on the other side to trust them. This is obvious in journalism, which derives its value from its ability to engender trust in its claims about the world, but has increasingly become divided into more explicitly partisan outlets, each offering its own hysterical version of reality to its own niche audience.

But it has happened throughout the professional world. In the summer of 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and public outrage about the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, a group of more than a thousand public-health experts and practitioners signed an open letter on large public protests. Acknowledging that mass gatherings increased the risk of transmitting the COVID-19 virus, they wrote,

However, as public health advocates, we do not condemn these gatherings as risky for COVID-19 transmission. We support them as vital to the national public health and to the threatened health specifically of Black people in the United States. We can show that support by facilitating safest protesting practices without detracting from demonstrators’ ability to gather and demand change. This should not be confused with a permissive stance on all gatherings, particularly protests against stay-home orders. Those actions not only oppose public health interventions, but are also rooted in white nationalism and run contrary to respect for Black lives. Protests against systemic racism, which fosters the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 on Black communities and also perpetuates police violence, must be supported.

Rather than compartmentalize their professional judgments from other considerations and priorities—explaining the risks of large protests regardless of their political content and then separately and in a different context expressing whatever views they might have about that content as citizens—they openly denied not only the possibility but even the desirability of detached professional advice, and so of a professional realm distinct from the political or cultural.

This mode of thinking now dominates the culture of much of the American academy as well, in a way that has flattened and enervated the spirit of inquiry on many campuses. If the purpose of the university is to engage in a partisan cultural struggle, then providing a venue for minority views to be heard is not only a distraction but also a betrayal and failure of its mission. The notion that the pursuit of the truth requires open debate is, in a sense, now twice removed from campus culture, because it assumes not only different means from those that come naturally to many academics and administrators but also different ends. It implies that the university operates in a different sphere from our political and cultural struggles—not entirely disconnected from them, but separate and distinct. And that notion strikes many professors, students, and campus leaders as a moral failure of nerve.

The blurring of boundaries has deformed swaths of American religion too, and for a similar reason. If the cultural left increasingly conceives of the academy as its own turf in a struggle with the right, many religiously conservative Americans view the church as their turf in a struggle with the left, and recoil from any notion that religion might actually serve a different, higher purpose that should put our cultural debates in perspective. The result has been a growing identification of religious faith with political and cultural partisanship.

We all find it difficult to sequester or contain our partisanship, and to engage with people on different sides of our cultural conflict on equal, friendly terms in those spheres of our lives that aren’t about cultural conflict. Indeed, we find it difficult to conceive of such separate spheres at all. Everywhere you look, people seem to be dragging culture-war differences into spaces where they don’t belong, and in ways that make it awfully hard for us to trust each other, to live together, and to do our common work.

Everywhere you look, people seem to be dragging culture-war differences into spaces where they don’t belong, and in ways that make it awfully hard for us to trust each other.

We do not do this out of malice. On the contrary, we often do it out of a sense of moral responsibility, albeit refracted through a broken culture. The debates that divide us are important, and the stakes involved are often high. This leads us to assign great moral worth to partisan identities. And because we now tend to equate expression with action in our political and civic lives, we put great value on the assertion of the proper ideals. We want to know that we are among friends, wherever we are. So affirmations of a cultural identity we share put us at ease—it’s good to know that my doctor is not a bigot, that your pastor loves America, or that our cell-phone company cares about voting rights and not just the bottom line. But expressions of a cultural identity not our own put us on edge, and leave us unsure whether we can trust that doctor, worship in that church, or keep doing business with that company.

As a result, we are constantly struck by a sense that the people around us aren’t quite doing their jobs, and are instead engaged in partisan combat where it doesn’t belong. That in turn leaves us exhausted and embittered, lacking a meaningful refuge from conflict or a durable wellspring of mutual trust.

The Chimeric Ethos

It is tempting to describe all this as the politicization of non-political realms of our experience. But that can’t quite be right, because the unease we experience in other domains of American life—that sense that people aren’t quite doing their proper work and have been overcome by toxic hostility instead—is at least as acute in the political realm itself.

Even a casual observer of the US Congress in the past few years, for instance, would have to conclude that its members have forgotten what their jobs are. Congress is inherently political, of course. But what its members do now would be better described as performative panic and rage than political action. They frequently use the institution as a platform for culture-war theatrics rather than a venue for bargaining over public policy. And of course, they’re just responding to the electoral incentives that always motivate politicians: Their voters, or at least the most intensely engaged among them, are demanding culture-war theatre, and are often participating in it themselves as well, on social media in particular. Our political culture has become increasingly hostile to traditional policy debates and increasingly interested in a kind of rhetorical warfare disconnected from reality.

Our politicians, like so many other professionals, have let the spirit of some other endeavour distract them from their proper work. But what is that endeavour? Whose job is everyone doing instead of their own?

The answer is no one’s. What we’re witnessing is the crossing of boundaries between distinct spheres of action yielding a new mode of action that really has no proper place. The brew of culture-war animosities that increasingly dominates many arenas of American life is a mix of entertainment and politics that combines the worst of both. It is a chimerical ethos of performative conflict.

In biology, a chimera is an organism that contains a mixture of different species, formed by fusing genes or tissues. But the term has its roots in Greek mythology, where it describes a fire-breathing monster with the head of a lion, the body of a goat, and the tail of a serpent. The ethos of our culture war is such a monstrous creature born of an unholy fusion—it’s not just out of its proper context, it is a wicked blend of attitudes that has no proper context.

Social scientist Richard Hanania captures one facet of the problem in these terms:

In the 1990s, politicians were boring, and politics attracted mostly boring people, which made the entire discourse smarter. Today, the lines between politics, pop culture, and reality TV have all become blurred, and I think we’re much worse off; people whose energy would have once been focused on pro-wrestling now opine on the most important issues of the day.

The same is true in reverse: People whose energy would have once been focused on the most important issues of the day now comport themselves as though they are engaged in pro wrestling. The spirit of our political culture and the spirit of a perversely confrontational entertainment culture have become blended. And the resulting mixture—which is perfectly adapted to dissolve all boundaries—has permeated every realm of our common life and begun displacing the particular character and mode of integrity of nearly every major institution. In the absence of distinct vocabularies for distinct parts of our lives and our society—different professions, institutions, circumstances, and times—we are left with an overarching vocabulary of conflict, and end up playing out that conflict in every realm of our experience.

It is in light of this dynamic that we can really see how important the concept of distinct and separate spheres of life really is to our contemporary social crisis. The problem we face is not caused by politics overrunning its proper boundaries, but by the emergence of a blended ethos that has its roots in the breakdown of boundaries to begin with.

The problem we face is not caused by politics overrunning its proper boundaries, but by the emergence of a blended ethos that has its roots in the breakdown of boundaries to begin with.

That ethos has overwhelmed our politics just as it has overwhelmed everything else. It can’t be contained, because it doesn’t belong anywhere. And so it must be rejected and driven back by a conscious resistance.

Setting Boundaries

The resistance we need must begin by protecting the distinct characters, cultures, and modes of integrity of our distinct institutions, and so making sure that we aren’t just using them all as venues for declaring our cultural allegiances.

By allowing the chimeric ethos of the culture war to infiltrate every part of our lives, we have come to mistake the mores of cultural-political combat for all-purpose norms of social interaction. When we ignore them at work or in church, and just do our work without regard for party, we feel like we have made a sordid concession. If our entire common life is one big yes-or-no question, then we must always make sure to answer it correctly.

But that is not what our entire common life consists of, and acknowledging that fact need not mean cordoning off your conscience. There are core moral commitments that must apply to every part of our experience. We must always respect the equal dignity of others, and live by the truth and not by lies. We can never let economic imperatives or team spirit overwhelm our fundamental religious and ethical obligations. But such core matters of conscience leave a lot of room for legitimate differences and circumstantial norms. And they are broad enough to let us apply distinct standards to distinct circumstances.

There are, after all, standards of integrity that are particular to different spheres of action in our lives that we need to respect within those spheres, but that we can put aside at other times. A judge must be impartial in his court, but not on the sidelines of his daughter’s softball game. A psychologist can lose her patience with her friends. An activist, a plumber, a father, and a neighbour can be the same person in different circumstances, and that person should behave very differently toward those with whom he interacts in each case.

Think again of Michael Jordan’s reticence to enter the political arena as an athlete. It did not cause him to stay out of a Senate race that mattered to him altogether. He made a financial contribution to a campaign he supported—acting in one of the ways available to a citizen in the civic and political arena. But he declined to traffic in his celebrity in that arena, because he had not earned his celebrity there. “I wasn’t a politician when I was playing my sport.”

Such compartmentalization is not an alternative to an integrated moral framework for our lives but an embodiment of such a framework. Properly conceived, it is a grace given to our limited selves from beyond ourselves—a reminder that we are not fully merged with the world and defined by our society’s categories, but have our own dignity and agency, shaped and provoked by distinct invitations and circumstances. And it is a way to moderate our partisan passions and to recognize the multifaceted complexity of other human beings. No one is simply a partisan. Everyone has a more layered array of identities. That’s why we can respect people and engage with them in those domains that are not set out for cultural contention but for cooperation.

This is not to say that our cultural debates should have no bearing on the rest of our lives. A heightened awareness of abuses of power by our society’s elites, or of systemic prejudice, can be a force for good, needless to say. It makes sense for institutions to be open to critiques and to new understandings of their own missions rooted in new insights about power and order. But those cannot substitute for institutional purposes altogether, or else it will become impossible for our society to engage in the essential missions of our different institutions—cultural, religious, educational, political, economic, and otherwise. Such critiques cannot become the only ways we value human persons. They are mostly correctives—vital, but as supplements and not substitutes for how we think about the world.

A recovery of the capacity to compartmentalize and discern the appropriate venues for cultural conflict is essential, therefore, to the recovery of the capacity of our separate institutions to do their work and gain our trust in their distinct domains. It is also necessary for the restoration of their ability to form us in their particular modes of integrity. If we all get formed only in the wide-open public space of our democracy, we are likely to be formed only for a kind of performative expression. But in the particular spaces of different institutions—with their different purposes, characters, and sorts of expertise—we can be formed for more constrained and therefore more authoritative and effective action too. And by better respecting the distinct formative features of different institutions in our lives, we can also hope to form distinct elites in each, rather than one class of interchangeable and overconfident elites locked in combat with one opposing class of frustrated populists.

Finally, and perhaps most important, a restoration of some boundaries between distinct domains of life could allow us to restore the vital link between particular institutions and particular places and people—that is, particular communities. As Seth Kaplan of Johns Hopkins University has put it, “Many of today’s social entrepreneurs don’t lack commitment or a desire for change; the problem is that their commitment is channeled toward causes rather than places, projects rather than people. We need a movement that is horizontal, not vertical; one that is driven by networks of place-based individuals rather than dictates from above.” Social change that recognizes these distinctions would make it possible to bring together people whom our rancid culture war seeks to divide from each other.

Our complex society breaks down along many axes, not just one, and for that reason it is also unified along many axes. People who disagree about abortion might nonetheless share a love of nature or of the New York Mets, or a devotion to the nursing profession, or a deep religious faith. If we let our society evolve in the direction of a single, all-encompassing cultural conflict, such people could find no way to overcome what keeps them apart, and would be left always approaching one another with suspicion. But if we come to see some separate spheres of life as distinct yet overlapping domains of human action, we can hope to better reflect the constructive complexity of our gloriously diverse free society, and so to build out spaces for common efforts, common enjoyments, and common loves despite our differences.

That would mean not only putting up with people who vote differently than we do but also finding ways to admire them and learn from them—even if not about how to vote. It would mean recognizing the humanity of our neighbours, seeing that expertise in one arena does not imply authority in another, and grasping that setting bounds on the reach of our cultural combat is not just a pragmatic concession to civility but also a broader path to the fullest truth about the human person. It would mean acknowledging that, in a properly ordered society with appropriately bounded spheres of action, some socialists make fine heart surgeons, some libertarians are pious Jews, and some Republicans buy sneakers too.