I

In the opening paragraph of The Art of the Novel, Milan Kundera discusses two lectures by Edmund Husserl on what Husserl calls the crisis of European humanity. “For Husserl,” Kundera writes, “the adjective ‘European’ meant the spiritual identity that extends beyond geographical Europe . . . and that was born with ancient Greek philosophy.” Kundera goes on, “The roots of the crisis lay for him at the beginning of the Modern Era, in Galileo and Descartes, in the one-sided nature of the European sciences, which reduced the world to a mere object of technical and mathematical investigation and put the concrete world of life, die Lebenswelt as he called it, beyond their horizon.”

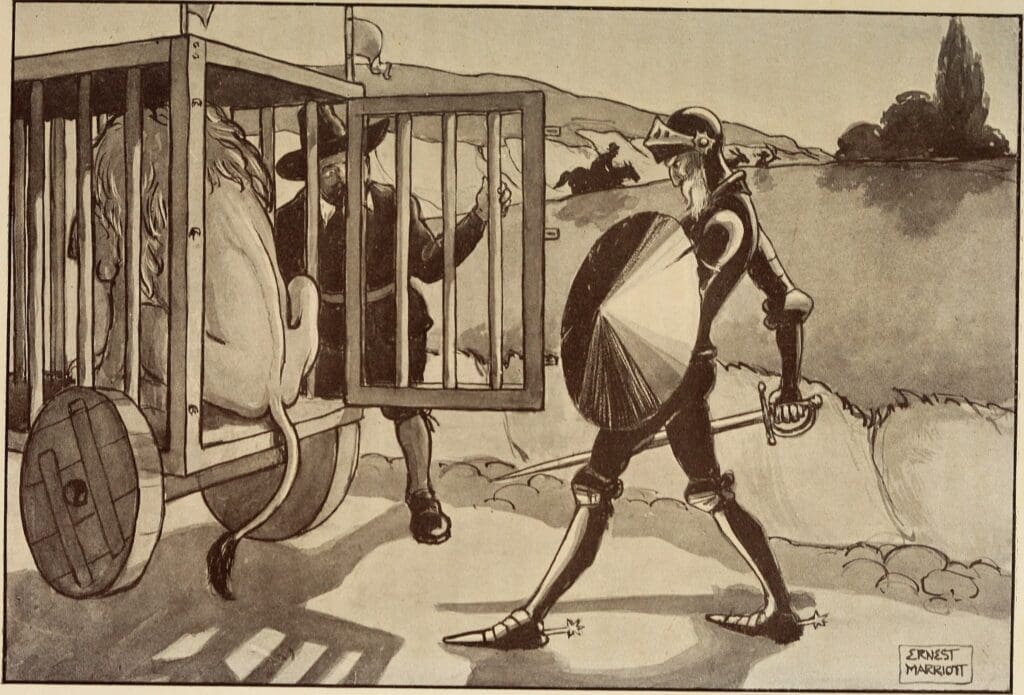

Kundera, however, claims that “the Modern Era is not only Descartes but also Cervantes.” “If it is true that philosophy and science have forgotten about man’s being, it emerges all the more plainly that with Cervantes a great European art took shape that is nothing other than the investigation of this forgotten being,” he writes. “As God slowly departed from the seat whence he had directed the universe . . . Quixote set forth from his house into a world he could no longer recognize. In the absence of the Supreme Judge, the world suddenly appeared in its fearsome ambiguity.”

It was perhaps this “fearsome ambiguity” I was unconsciously operating under when, in 1983, I decided the poetry of my grandmother’s life very well might take the form of a short story. I bought a lavender spiral notebook—not a colour I would choose, but it was the only thing left at the stationery store—to use for beginning my new work of fiction. I had graduated from college that year and was living a vastly different life from that which was connected to my grandmother and immediate family. That made me want to begin drafting something that, in the tradition of Cervantes and all novelists, was an exploration of being, time past, present, and future, in the face of my own uncertainty about my identity.

The years between 1970 and 1980 mark the difference in how the world felt to me between hearing “American Pie” on AM radio in a ceramics studio when I was ten and seeing Grace Jones pop out of a coffin one Halloween night at the Underground in Union Square when I was nineteen. It’s not a hell of a span, but it was a massive span in consciousness for me; the latter part of it swallowed the former. On the far side of that span stands a woman in a London Fog raincoat, navy, cold October rain landing on her defiant cheeks as she persists in raking leaves in the Octobers of my childhood. She’s working something out behind her tense brow, thinking maybe of the light she had kept on in the hallway years ago in Philadelphia “for when Freddie woke up in the middle of the night with pain.”

The woman is my grandmother. Freddie is my deceased uncle, who succumbed to leukemia at fourteen, before I was born. And that quote is from my mother. I used it to open a short story I began in 1980 and never finished, possibly the same short story I picked up again in that notebook in 1983 after exiting NYU. Whatever remained in my grandmother’s mind’s eye those chilly weekend Saturdays when she raked has remained in mine, though I came to discover that at that time she had recently lost her husband, my grandfather, and one of her sisters, my great-aunt Antoinette, who was legally blind. Nettie, as she was called, did all the shopping for the family and was a whiz with money. She could do figures in her head because she had been coached at a school for the blind, and in my admiration of her skill I learned to imitate her.

I have a flavour in my mind that comes on Sundays and transports me to the Philadelphia of the seventies. Late autumn, cold days, traffic sounds in the background, the PSFS Building visible through a small hallway window almost like a skylight illuminating the third floor of 625 Fitzwater Street, where I could find myself at any given time, a few feet from my uncle’s bedroom, where cologne sat on a bookshelf with Walker Percy’s The Last Gentleman and my nerves grew alert to a crystal blue sky and the red warning light atop the radio tower that signalled for aircraft. Away from desolate Jersey, where my family lived, this was the life. But it was not the PSFS Building and the red warning light that made my nerves crackle. It was the people who inhabited me: Catherine Scioli, my grandmother, and her two sisters, Amelia and Antoinette, better known as Millie and Nettie, and Virginia Plummer, mother of my best friend across the street, and various aunts and uncles who were settled by then and could offer family stability that made me feel filled in. The patch of blue sky in that hallway window and the blinking red light—the entire city, really—held a mystery and a belonging that has since turned to grief.

All the people who inhabited it are now dead. My mother can get forlorn about that, as can I when I return to Philly and expect to knock on my grandmother’s door and have her open it. As my mother ages—she is eighty-seven—she says she senses her mother next to her sometimes. This is not unlike my grandmother, who in the same position later in life, in her nineties—she died at ninety-four—said my grandfather would come up to her and put a reassuring hand on her left shoulder. He died in 1983. Shortly afterward, in February of the next year, my father’s drinking problem peaked when he drove into a tree and was hospitalized. He said my grandfather—his father-in-law—was sitting next to his bed, that he knew this wasn’t part of the hallucinations he was experiencing. My grandfather raised his hand in that Italian way where you put your fingers together to express what gives?, shook them at him, and said, “What are you doing to yourself?” My father emerged from the hospital sober, went to rehab, and stayed sober until he died.

I learned of my grandfather’s death sitting on the bed in my dorm room the morning it happened in November. I packed and headed to Port Authority for a bus to Philly. The look on my grandmother’s face after the funeral was over as she sat on the couch full of people and put two fingers against her forehead and leaned forward made me turn my head away. I chided myself for letting my relationship with my grandfather fall by the wayside as I got immersed in the quest for new life in New York.

My great-aunt Nettie was named Antoinette because her birthday is June 13, the feast of St. Anthony of Padua. I think of her every year when June comes around. Last week I was doing laundry the day before, June 12, and one of my Adidas no-show socks disappeared. When I couldn’t find it, I went back upstairs and prayed to St. Anthony, and the next morning, the 13th, the sock was on the floor under my bed, where it had probably fallen as I’d emptied the clean laundry in haste. This isn’t the first time the man from Padua, goaded by my great-aunt, has reached out. My preoccupation with losing a sock is petty, but those who know me know I’m all about closure, and closure is what St. Anthony of Padua gives.

My aunt’s experiences and what I knew of them are an example of how to trust the things right next to us as given by the Creator to educate us to his ways.

Faith requires that you meet your patron halfway, and for reasons unbeknownst to me I have always found it easy to do this with the saint of lost objects—a relationship I do not have with other saints. If the details of everyday life are what God uses to sanctify us and reveal himself to us, then my aunt’s experiences and what I knew of them are an example of how to trust the things right next to us as given by the Creator to educate us to his ways.

My mother told me that my great-grandmother, upon learning that her daughter was visually impaired, sent her to a school where she was taught to use her mental capacities to carry out everyday tasks, like feeling for things and working well with figures in her head.

But that wasn’t the half of it. When I was eleven or twelve and decided to stay in Philadelphia with my grandparents one Easter because I dreamed of moving to the city when I grew up, I accompanied my aunt on her Tuesday shopping to the Ninth Street Market, an outdoor Italian market blocks from the house. She took her purse and her metal shopping cart that clacked against the pavement as I walked abreast of her. When I asked her how she saw where she was going, she explained that she had done it for years. In her dowager coat—it was still chilly—and practical shoes, she lumbered past Seventh and Eighth Streets, to Ninth, where we turned left and walked south.

The market was a mishmash of delivery trucks, strung lights, and vegetables and fish piled in crates on the street—a festival of smells and colours, especially when it was cold out and the holidays were coming. As my aunt went in and out of each place—Italian cheese stores, Esposito’s, the butcher, and others—with her small, zippered purses containing her cash and change, people would greet her and show her what they had. I remember the butcher once handing her a cut of meat on a brown slice of butcher paper. She held it up to her face and said, “This is no good. Give me another cut.” The butcher promptly took it back and gave her something better.

Outside I said, “How’d you know that wasn’t what you wanted?”

“I just know how to tell by now,” she said.

In later years, even as far as my college years, she continued this every week, spending her public-assistance money on grated parmesan, ground meat, produce, and De Cecco pasta (the top-notch Italian foods you could only get on Ninth Street, as everybody called the market) and sending packages to my grandmother’s kids’ families—my own, my aunt’s, my uncle’s. I can still remember the white-handled Esposito’s shopping bags coming out of my grandfather’s car with blood seeping through from a steak or pound of ground beef that had come unpackaged in transit.

In the winter of 1983, I moved into my first apartment, a studio walk-up on the Upper East Side I found in the New York Times real-estate classifieds after praying to God and making a deal. I saw the Neediest Cases Fund and sent in a thirty-dollar check, and in turn asked to get a good apartment in order to stay in New York after graduating from NYU. And, well, there it was. Aunt Nettie and my grandmother sent with my mother and aunt packages of cheese, ground meat, sausage, and skinned chicken thighs because they figured as a guy I didn’t know how to shop, and it would give me ideas for how to cook so I didn’t waste money on restaurants. The apartment had one window in the kitchen and another in the bathroom, a slanted floor that my mother and aunt giggled about as they tried to make me clean it up and make it habitable, and a large claw-footed bathtub without a shower. My father came later, and his solution was to hammer a mount on the wall above it and connect a rubber shower hose. The toilet had a black seat cover and a wall-mounted tank that you flushed with a pull chain.

Once, my grandmother and great-aunt themselves made the trip with my mother and aunt. My grandmother sat smoking at the white, Formica-topped kitchen table I had bought. There was something about a white kitchen table that made the place more of a home. The table against the back wall had a centrality about it and reminded me of the style of living in their Philly row houses. They all approved of it that day and laughed again at the slanted floor.

I adopted a black tuxedo cat from the ASPCA nearby, and like many adopted cats she developed a GI issue. I called the ASPCA, and they told me to bring her back for treatment, which I did. They also gave me free drops to administer to her. I felt bad keeping the poor cat confined to the travel box they had sent her home with me in, so I carried her in my arms back up from York Avenue to my apartment. As I neared Our Lady of Good Counsel Church on Ninety-First Street, a couple of things happened simultaneously. First, two kids, a boy and a girl, maybe eight, nine years old, broke free of their mother and came running toward me to pet the cat. And second, the medication began working, so that the cat went rigid in my arms and started emptying her bowels over the front of one of two Brooks Brothers summer button-downs I’d bought on sale the previous summer. I lowered her to the ground to let her finish and tactfully fended off the kids by calling out without seeming aggressive. They stopped dead in their tracks when they saw the cat was sick. Later, after I’d gotten the cat home and washed the shirt, she already looked more pert from the first washout of her guts, and I understood that the mechanism of the drug was to have a cat void her bowels over and over to rid her of the parasite. Soon she was sitting on my head each morning, reminding me to get out of bed and feed her. I was happy to be the kind of person at twenty-three who knew how to medicate a cat.

No matter where my life veered and no matter what sins I was enjoying, I still belonged to the church and it could include me even when I wanted to stay a bad boy.

I got a rejection from Columbia’s School of the Arts for an MFA in fiction that year, and during Holy Week, because my absence from the family at Easter was perceived as a tragedy, another package arrived from Philadelphia full of ricotta pies and other comestibles. I had not gone to church through four years of college at NYU. This is a fact that had my mother pulling her hair out. To make myself feel better about the MFA rejection and missing my family during the holiday, I went up Our Lady of Good Counsel’s granite steps and confessed my sins to one Father Doyle, who, despite my confusion, gave me absolution and said, “Whatever you do, stay close to the church.” This did two things for me: it convinced me that a white-haired priest from Queens who looked like he’d never left the fifties was not in any way the bully I had expected him to be but rather seemed gratified that I’d shown up and that he could absolve my sins; and it made me feel like no matter where my life veered and no matter what sins I was enjoying, I still belonged to the church and it could include me even when I wanted to stay a bad boy.

It was in the recall of my great-aunt and my mother, the family that had brought me into the world, that the nature of my actual self became apparent. Despite what I wanted to think I was, the real me kept surfacing in odd little memories and quirks. One of these was an eighteen-carat gold cross Aunt Nettie bought for me in Naples when she travelled there to meet our relatives as they were preparing to immigrate to the United States in 1967. People would notice the cross at beaches or sleepovers when they saw me shirtless; I would cringe at being labeled a “guido,” though I was the farthest thing from one and did not in fact possess any wife-beater undershirts, as they are called. Some never raised questions about it; others found it off-putting. It hangs on a serpentine chain, and sometimes I have added a gold miraculous medal to it, or attached the medal by itself, which I purchased in 1991 in tandem with my girlfriend at the time. The relationship died soon after, but the medal didn’t. I was trying at the time, emerging from my NYU days, to live the bohemian life of an East Village squatter, but I still had Brooks Brothers taste, which gave me an irrevocable dad look. Like all Brooks Brothers clothes, the shirts lasted for years. I wore the one my cat had shit on when my parents came to Brooklyn to meet the Jewish-cum-Catholic girlfriend I’d bought the medal with. I thought I was about to settle into the life of a married guy, a lifestyle I resisted because I couldn’t grasp in those days that it was possible to be a writer without being a bohemian or an eccentric. Things like a chain from Naples given to me in first grade, packages of food from Philadelphia sent to New York, or the vision of another great-aunt, Millie, coming up Seventh Street the year my sister and her husband rented the old Levi’s hotdog establishment near South Street and opened a seafood takeout—these are the things that tell you your life has already been earmarked, despite all the stupid notions about yourself that don’t hold up with time. The Brooks Brothers shirts, the cross, and the miraculous medal are curious identity markers. They have a staying power the adopted postures and stances I took from my artsy friends in college lacked. My friends may have managed to run from their roots, but all those perceptions about who I was fell through my fingers like water until I finally admitted, This is who I am and I like it.

As a kid I was a competitive swimmer, and in adulthood I picked up swimming again because I cannot stand the artifice of indoor gyms, and I don’t run. For years in Washington, DC, where I live, I have swum at the Wilson Aquatic Center, alternating at times with the Takoma Park Aquatic Center when Wilson has been closed for repairs. This past spring, as I returned home one day from Takoma, it occurred to me that the miraculous medal wasn’t on me, and I remembered that I had hung it on a hook in the locker where I’d left my things during the workout rather than dropping it into my backpack like I usually did. “Can you believe it?” I said to my mother on the phone the next day. “That chain Aunt Nettie gave me when I was seven from Naples when she went to visit the cousins, I left it in the locker at the pool yesterday. Kaput.”

“Pray to St. Anthony,” my mother said.

“I know, and I already did,” I told her.

Then talking over one another, we both said, “His feast day is Aunt Nettie’s birthday.”

The next day I went to the pool and headed to the same locker, one of the few that hasn’t had the latch broken with the big metal clippers thieves use to cut Master Locks and rip people off. I opened it, and the medal was hanging from the hook where I’d left it the previous day.

My friends may have managed to run from their roots, but all those perceptions about who I was fell through my fingers like water until I finally admitted, This is who I am and I like it.

This was roughly a month before June 13, 2023, almost forty years after Fr. Doyle told me to stay close to the church. Like me in my Brooks Brothers shirts, Fr. Doyle was what he was called to be, a father, and his recommendation, a fatherly one I found irresistible in spite of myself, has allowed me to never successfully remain a bad boy.

This is what strikes me now about Kundera’s words. I once believed that to write a novel, a story, or anything, you had to forgo all the givens of your own identity. What had been lost on me was the truth that, before you can write anything—not necessarily a novel, not necessarily fictional—you need a voice, and the unseating of the Supreme Being in post-Cartesian culture, in other words the culture we have inherited, leaves us fumbling to discover our voice. It is certainly not a culture that prays to St. Anthony for lost things. It is a culture, unlike the Greek, Hebrew, and Christian worlds that made us, that no longer takes for granted anything beyond this world. Without that, we invent rather than accept who we are. Last year I got around to finishing that story that opens with the woman in the raincoat in October, my grandmother. It turned into a novel, taking me all this time to write it. It was one of the truest things at the core of me, yet I had overlooked it. I had thought, like Don Quixote, that I had to build an identity for myself, while the one I had was far easier to settle into.