R

Recently I visited an art exhibition housed in the old waiting room of a station near my home. It had been shut up for sixty years, the commuters left to shiver on the platforms, but the Victorian grandeur of the vast hall is still visible. Artist Sarah Sze had placed an incongruous installation amid the peeling green paint and crumbling stonework—a globe made of small white screens, flickering rhythmically with images culled from the internet. Over the top a clock ticked loudly as outside trains whooshed to a stop, disgorged their passengers, and surged onward, creating a hypnotic techno soundscape.

The exhibition is designed to express the “velocity and volatility of living in a smartphone age” and the artist’s experience of being “in the middle of an extreme hurricane where we are learning to speak through images at exponential pace.” The location was chosen for its echoes to the last time our relationship with time shifted so dramatically, at the coming of the railways. It was only the introduction of “railway time” in the 1840s that unified Britain’s then organic, local, ancient approaches to timekeeping. Up until the end of the eighteenth century, time had been determined for each community by sundials, meaning that the local standard time could vary significantly. This obviously made railway timetables difficult to write. Similar time-standardizing processes happened wherever timetables required distant lands to synchronize. Technology can liberate, but it also shapes us around its needs, to form us toward efficiency.

As I made my way down the grand old staircase, I could see the church directly opposite the station, also built in the Victorian era. I hesitated outside it, wondering if I should hang about for the mid-week service. I knew that if I did, I would experience not frantically flickering images but a set of words and songs and actions that reach back over the centuries to an age before railway time, before clock time. I might pray “Help us, dear Lord, to number our days” from an ancient book written in an age in which time was clearly a gift rather than a resource. I would sit in a similar wood and stone hall and emerge not pulled hurriedly into the restless future but steadied and settled by being rethreaded into time’s unspooling. My day would be shaped by joining a slow and patient song that started before I was born and that will be sung long after I am dead.

Standing on the street between the station and the church, these thoughts flashed past me. Then I got out my phone and hurried home, scrolling.

Rowan Williams says that “undifferentiated time” is one of the hallmarks of secular societies, and we are all dancing to its catchy, repetitive tune. Largely detached from the seasons, time feels like a headlong linear rush of news cycles punctuated by the commercial breaks of Black Friday and Starbucks Red Cup Day.

Williams believes that one of the hidden gifts of communal religious practice is the way it helps us locate ourselves in, and stay in fruitful relationship with, time.

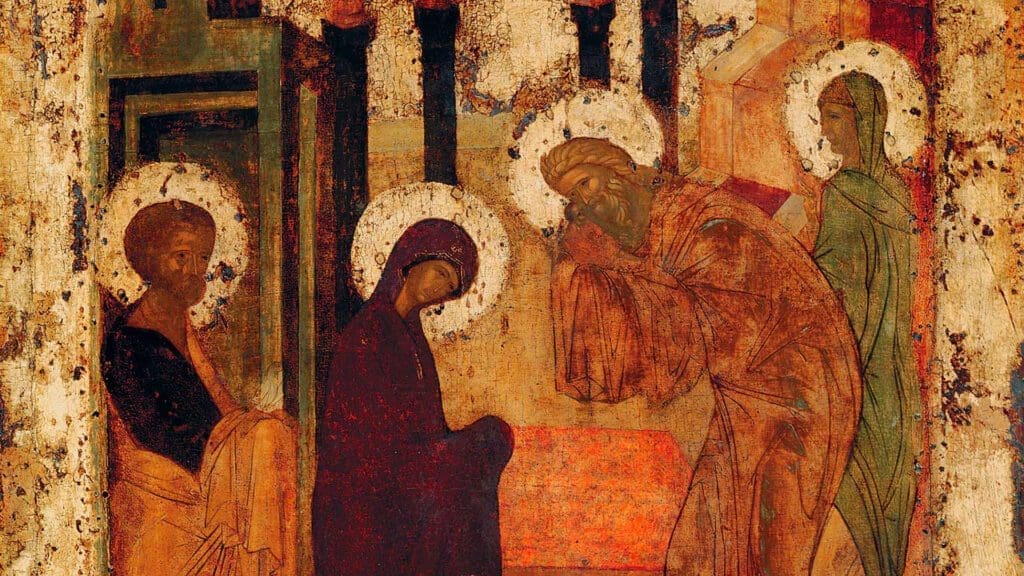

He argues that liturgical traditions which observe the church calendar have a particular strength in this area. The steady rhythms of feasts and fasts, the narrative thread through the weeks and months, prevent time from being just about an accumulation of status and comfort. They instead make it an “accumulation of meaning.” By repeatedly returning to these stories, we discover new aspects of them, and of ourselves, bringing to them a slightly different person each year. We can connect whatever is going on in our own life at that moment with the “steady, regular, rhythmical patterns laid out in the language and practice of a religious community.” Time begins to feel neither straightforwardly cyclical (as in many early agrarian societies) nor shapeless and accelerating (as in ours); rather, it becomes a deepening spiral of meaning.

Many churches now do not observe the church calendar, or do so only half-heartedly, not fully certain what they are doing it for. Isn’t it just a convenient structure, a way of making sure we cover the highlights of this book we’re supposed to be building our lives around?

Theologian Andrew Root argues, in line with Williams, that the church is failing in part of its calling when it syncs to the clock of the industrial and technological age. Part of what has gone wrong with the church, he says, is that we have ceased to resist the commodification and acceleration of time. He invites the church to reclaim what used to be a central part of its calling: to be the custodian of sacred time.

From the earliest days, time looked different for Christians. They already stood out in how they structured their week, steeped as the initially largely Jewish converts were in the practice of Sabbath. Abraham Heschel notes that Romans such as Juvenal and Seneca responded to the Jewish habit of abstaining from labour on the Sabbath with contempt. Their opinion was that “the Sabbath is a sign of Jewish indolence.” The new followers of Jesus took this already powerful practice and added to it with a full weekly rhythm. “The church,” Root explains, “enacted the narrative of Jesus’s final days each week, correlating their own being to Jesus’s own time.”

This ragtag band of persecuted outcasts moved in eschatological time, not the frantic, extractive hurry of imperial time. The ending that humanity is always running from no longer threatened them, Root argues. “The time they shared in and anticipated was so full that even death, time’s great dark promise, had no claim on them, for even while they were in time, they nevertheless partook in eternity.”

After the fall of the empire, the church remained, the strength of its committed and synchronized communities allowing them to survive the storm. The church had grown from a small sect moving to its own beat to being the keeper of public time throughout the medieval and premodern world. Priests, monks, and nuns “kept sacred time through the rhythms of their own bodies and lives.” The monasteries were the clock of society, ticking with the kneeling and rising, fasting and feasting, working and giving of those consecrated to the task. Those outside the walls of these monastic communities, focused mainly on farming, fighting, child-rearing, or creating, knew that “they could reset themselves, connecting again to sacred time, even after a long harvest or a bloody war. . . . The objective was to join the fullness of gathered time.”

Our age is secular because time itself has been emptied of the sacred. We have given up our custodianship and joined the headlong sprint of secular time. And in so doing we have made ourselves unnecessary.

How much does your local church function as the clock of your community, as a site where the wider population can reset themselves to sacred time by joining its steady and patient rhythms? I know of some monasteries and convents that function in a faint echo of this, for those who know they are there, and city-centre cathedrals with enough footprint that their daily services still hint at a different timetable, but no local churches. We do not mark time communally by the bells for prayer but by the buzz of a device often strapped, or as good as strapped, to our individual bodies. Sacred time has evaporated because the church stopped living in it. Our age is secular because time itself has been emptied of the sacred. We have given up our custodianship and joined the headlong sprint of secular time. And in so doing we have made ourselves unnecessary.

Earlier this year I hosted a live recording of the podcast I host, The Sacred, with Oliver Burkeman. His most recent book, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, has been a New York Times and Sunday Times bestseller, proving how hungry mainstream readers are to think about time. Burkeman describes himself as a time-management obsessive in recovery, having realized how futile his attempts to “reach maximum efficiency” and “get to inbox zero” really were. I was struck by how humane, and even theological, his conclusions about time are, given he describes himself as interested in religion (especially Buddhism) but non-aligned. He decries the dominant secular “conveyor-belt time” and hankers instead after “deep time.” He recommends readers surrender to their finitude and contemplate the reality of death, and encourages them to commit to communities in ways that impinge on their convenience and autonomy.

Burkeman argues powerfully for the importance of collective time, the sharing of regular rhythms and practices with other people. For his audience, it sounds surprisingly radical. In language that could easily be heard in a sermon, he expounds the way collective committed rhythms actually liberate us, in contrast to the individualized, flexible, autonomous schedules we mainly keep, which Burkeman calls “the freedom to never see your friends.”

Inversely, he argues, real “freedom . . . is to be found not in achieving greater sovereignty over your own schedule but in allowing yourself to be constrained by the rhythms of community—participating in forms of social life where you don’t get to decide exactly what you do or when you do it.” As I said to him, this sounds a lot like church. Or at least, what church is supposed to be.

Communal time is not just (counterintuitively) more convenient; it’s more pleasurable. Burkeman quotes a description of the repetitive sequences of marching together, which form a key element of military basic training. “Words are inadequate to describe the emotion aroused by the prolonged movement in unison which drilling involved. A sense of pervasive well-being is what I recall; more specifically, a strange sense of personal enlargement; a sort of swelling out, becoming bigger than life, thanks to participation in a collective ritual.” Marching together feels good. Dancing together in time feels good too. The rush at the end of a successful choir rehearsal, or any collective, ritual-adjacent activity, is our bodies telling us that this is good for us. We are designed to be in sync—not legalistically so, but as a steady baseline rhythm we can improvise over and then return to. Without it, we are all just playing our own song, and it results in cacophony. Heschel called disordered time “the screech of dissonant days,” and if I get quiet enough, I can hear it.

With the loss of the clock of community we have lost the scaffolding for our relationships, the regular points of contact that didn’t require detailed scheduling and multiple cancellations to make happen. Loneliness is driven by many things, but a key one is surely that we all want sovereignty over our schedules and can’t make those highly individualized schedules sync up. Burkeman is right: our liberation from obligations means too many of us have ended up never seeing our friends. In these days we should name a love language for the willingness to be the one not just to say vaguely “I’d love to see you” but to get out a diary, suggest a concrete date, and doggedly refuse to let the planning thread drop until you are physically in a room together. Blessed are those people, committed rebels against loneliness, stylishly blowing up the railway lines of isolation, one at a time.

Perhaps we wouldn’t have to work so hard at this if the church hadn’t collaborated with the enemy in the first place. We have outsourced our formation largely to our passive consumption of culture, been too relaxed about how powerfully social liturgies—more subtle and more regular than our actual liturgies—shape our hearts and our habits. I’m more and more convinced that the way we structure our time—collectively, not only individually—is the key factor in our discipleship. The only way we can be formed to stay loyal to the logic of a different kingdom is to focus as much repeated, intentional attention on its stories and rituals and songs as we do on our phones, our televisions, and our shopping centres.

Repetition is what changes us, and our rhythms—consciously chosen or otherwise—are how we remember what we know, and let what we know change us.

Thomas More wrote, “Many things know we that we seldom think on. And in the things of the soul, knowledge without remembrance little profiteth.” His call was to repeated, deliberate meditation on the most important things as a way of training attention, shaping our very souls. Repetition is what changes us, and our rhythms—consciously chosen or otherwise—are how we remember what we know, and let what we know change us. Atheist philosopher Alain de Botton points out that our culture is allergic to repetition, associating it with “punitive shortage, presenting us with an incessant stream of new information—and therefore it prompts us to forget everything.” I think for the sake of my soul I need to learn to tolerate the boredom of repetition, to resist my constant snackish search for novelty. I want to find rest for my restless heart, made visible in my restless, scrolling thumb. Research on neuroplasticity and the power of habit only confirms what church tradition has always taught about formation—the repeated, committed choices we make day after day are the sum of who we are becoming. I don’t want to tick to the clock of the ever-accelerating internet, or the ping of my phone. I want to sing a deeper, older song.

For me, this does involve being a bit more reliable about showing up at church, not allowing lame excuses or petty irritations to keep us away. I’ve felt the need for stronger medicine though, so my family and I have moved into a tiny intentional community, just two families and guest rooms with a shared rule of life. Surrendering sovereignty over my time is often uncomfortable—especially when it involves getting up early to pray in our makeshift chapel, or turning down a free ticket to the theatre because Wednesdays are house night. It felt countercultural to commit to our rhythms as a default, and to require others’ permission to diverge from them. Part of me still believes freedom of choice, freedom over my time, will make me happy. But the slow formation of a shared rhythm, the way it grounds me and repeatedly orients my attention toward what I want to be formed by, is teaching me otherwise. That day, on the way home from the exhibition, I knew we’d be praying Compline that evening, that the benign peer pressure of community would mean I couldn’t skip it to work or waste time on my phone. It feels like a welcome counter-formation, a form of resistance to secular time. We are in no way functioning like the clock for our community, but people do seem to be drawn to what we’re doing, want to join the monastic rhythms, especially those who are not Christians themselves. Like Burkeman, they are burned out by conveyer-belt time. Our home is becoming a tiny, faltering attempt at keeping sacred time, and I can feel the difference.

Rowan Williams, again, argued in his BBC Reith Lectures that this is what freedom of religion really is: the freedom to do what late modernity sees as “wasting time” but what we call “keeping sacred time.”

I want a life made up of more moments like these, ideally with others. This is the song I want to dance to. And to do so I need to intentionally and doggedly turn down the volume on the techno beat of secular time.