The following are excerpts from two companion volumes, one written for those who are facing their own dying, the other for those who care for them and mourn them when they go. A Faithful Farewell, and A Long Letting Go (Eerdmans, 2015) are based on the writer’s experiences with family members and hospice patients and on the conversations she has had with medical professionals and medical students for whom death and dying raise practical as well as spiritual paradoxes.

A Faithful Farewell

We live longer now, and many of us die more slowly. Medicine and medical technologies keep us alive in ways that introduce uncomfortable ethical ambiguities. We have choices our parents didn’t have about treatment and care, including choices about how much of our care to consign to professionals and how to protect the intimacy and privacy of dying in the midst of loving people who gather to see us home.

This book is written for you, who are facing that second kind of death. You know there is no likely cure for your condition. You may continue to pray for a miracle of healing, but you also know that healing is bigger than cure, and that it doesn’t always mean prolonging this life. You know that illness and death bring new spiritual needs and enforce a different kind of hope.

And you know, as you live through this slow leave-taking, that dying involves a variety of difficulties, uncertainties, adjustments, and surprises. . . . I’ve tried to identify and address some of those in these short reflections and prayers: discouragement, embarrassment, boredom, curiosity, loss of privacy, opportunities for new conversations, family conflict, indignities, small losses along the way, moments of new awareness, misalignment of others’ efforts to help and one’s own needs, spiritual torpor, spiritual adventure, sadness, gratitude. Based on the hours I’ve spent at the bedsides of those who are living their dying, and on reflections about my own aging and death, I have written these pieces in the first person, hoping that will give them an immediacy they might not have otherwise, and make them more a sharing of a common condition than advice from across the chasm that divides health from illness. “We die with the dying,” Eliot writes, and so I believe we do. I hope these pages will affirm a solidarity that makes every dying an opportunity to awaken and open the heart.

Losing Control

. . . you will stretch out your hands, and another will dress you

and carry you where you do not want to go.

—John 21:18

As the medical supplies pile up in the bedroom and bathroom, the walker and the portable commode and the bedpan, the catheter and the waterproof mattress pad, I dread every loss of function and control. I dread the shame even more than the discomfort and inconvenience. I dread the exposure. More people have access to my body now. More people touch me, and in more places than I’m comfortable being touched. I know social protocols change with illness, and I know increasing dependence on others for personal care is a part of what I have to accept, but I still struggle with feelings of vulnerability and shame. Even as I try to protect it, it’s hard to love my failing body, though it has served me well for a lot of years.

One way to come to terms with all this exposure and dependence is to reconsider what it means to “become like a little child.” Although the most common reading of Jesus’ admonition to become like little children is to see them in terms of their trust, open-heartedness, and guilelessness, they’re also unself-consciously dependent on others for their care and feeding. Children are recipients. Well-behaved children learn to express gratitude, but even the ungrateful ones have a healthy understanding that they are not in charge, that someone else will take over when they don’t know what to do, and that there is safety, not shame, in being cared for. Being cared for is the first— and last—practice of living in community.

The Amish, I understand, teach that the sick, the elderly, and the dying are gifts to the community because of the love and care they bring forth. That’s a beautiful and generous way to think about what my “contribution” may be now to a community in which I used to be a lot more “useful.” Allowing others to be generous and tender, giving them occasion for the sacrifices of time and energy that deepen their investment in others’ lives, may seem like a necessary evil, but perhaps it’s a necessary good. I am still a participant. And I cling to Wendell Berry’s helpful observation, “Love changes, and in change is true.” The way they love me, and I them, has to change. May God help us all accept these changes with grace and kindness.

PAIN

If I speak, my pain is not assuaged, and if I forbear, how much of it leaves me?

—Job 16:6

On a scale of one to ten, how badly does it hurt? This nonsense question doctors like to ask doesn’t give me either words or images for the pain I’m in, or a strategy for dealing with it. Sometimes it seems more than I can bear. Is it a ten, or simply “off the charts”? Sometimes it’s bearable, but I still want and need immediate relief. Is that a six? I answer the question (sometimes after pointing out what a crude instrument of assessment it is) because it’s asked, but it leaves me wondering how to live with pain that may be partially abated, but isn’t likely to go away altogether.

Job tells the truth about persistent pain: “If I speak, my pain is not assuaged, and if I forbear, how much of it leaves me?” (Job 16:6). I’m not too interested in putting on a happy face. I’m interested in finding a way to tell and live what is true about bodily suffering, and finding some strategy that allows it to help my spirit grow toward God, not feed on resentment or fear. This may be a good time to reread Job, remembering it’s a story not about rescue so much as about divine encounter and about faithfulness that endures through the hardest trials because, though the ways of God may be incomprehensible, God is also our refuge and strength.

Physical pain is certainly, if nothing else, a reminder of the contingency of physical life. Faith gives me assurance that ultimately we won’t have to live on these terms, in physical bodies that are susceptible and frail and wired for pain signals that can be very hard to silence. But the promise of life in another condition doesn’t alleviate present pain. My belly hurts. My neck hurts. My back hurts from so much time in bed. It hurts to sleep on my side. I try what I can. I pray. I practice slow breathing. I imagine myself riding a wave when the pain crests. I find a place in my mind from which I can observe it with a certain detachment. I speak words of affirmation to God who holds me in these hard hours: “This is my body. This is my body. This is my body,” or “Jesus be with me,” or “I accept what I must. I ask for release.” Repetition helps. Sometimes holding a physical thing helps ground the flailing energies that make me frantic with pain—a cross, a smooth stone, a squeeze ball, a willing hand. I see why people pray with beads: they keep body and spirit linked when it feels as though the body is reeling off on its own crazed trajectory.

I accept pain relievers when they’re given. I ask for what I need. Sometimes I badger my caregivers for more of it. And sometimes I just turn into my pillow and beg for sleep. In all of these efforts I’m trying to reclaim Jesus’ promise to be with me always— always—and imagine as I close my eyes on the light that hurts them that I am held gently by the One whose light never hurts me, who knows my pain better than anyone else, and who needs no explanation.

ANGER

Be angry and do not sin; do not let the sun go down on your anger.

—Ephesians 4:26

I’m tired of being a good sport. I’m tired of exhorting myself to patience. I’m tired of being a good patient. I’m not even attracted at the moment to the notions of saintliness or heroism that inspired me wen I was a kid reading Bible stories and biographies. I don’t want this illness—or the pain or the inconvenience or the disappointment or the wracking tears that come in the night. I don’t want my family’s sadness. It all feels unfair, untimely, unappealing, and ungodly. Much as I’ve been taught that pain and death are part of the deal, that God is with us in all of it and meets us there, I’m having a hard time finding God in the fog of loss, and I’m pretty tired of looking.

Some evenings fury comes like a sudden wind and whips through my body, leaving every nerve on edge. I may have started the day in hope and good humor and laughed or cried or exchanged hugs with sweet friends who came by, but then darkness descends and, if I have any impulse to turn to scripture or prayer, it’s the psalmist’s imprecations or Job’s outrages I turn to. Sometimes I just reach for the remote and watch the most escapist movie I can find.

I’ve heard the answers pastors and theologians and wise teachers give to the great “Why” questions, but it’s impossible not to ask them. Why do we have to suffer? Why do I have to suffer? Why death? Why now? Why in this way?

When I’m awash in these railings I can’t really pray. Others have to do that for me right now. My heart is full of a kind of anger that makes me reach for an old word like wrath. It burns loud and it’s consuming. When it’s ignited it is fearful—though it’s “mine,” I’m afraid of it, myself.

But I may not need to be. Anger comes and goes, and somehow I weather it, and love eventually absorbs or dilutes or detoxifies it. Sometimes that love comes from a patient person at my bedside, sometimes by direct infusion like cold water poured into my burning heart.

I suppose some anger is a necessary release. I remember Maya Angelou’s helpful distinction: “Bitterness is like cancer. It eats upon the host. But anger is like fire. It burns it all clean.” I’m not too sure it always leaves me feeling “clean,” but the honesty of anger may prevent a more insidious soul-sicknesses— self-pity, false piety, depression, and the bitterness Angelou so rightly mentions as a state of mind and heart more dangerous than anger.

It comes over me unbidden. I can’t simply drive it away. It may be something to be borne like pain, released as soon as it can be, and reflected upon in tranquility, when that blessed gift, as it always has been, is restored.

LISTENING

If anyone has ears to hear, let him hear

—Mark 4:23

A friend of mine who has taught music for many years assigns her students to make a list of music they would want to hear if they were dying. Inspired by her, and because that day is coming, I have made one, though it gets emended with some regularity: Bach’s “Bist Du bei mir.” The second movement of Schubert’s Quintet in C Major. John Rutter’s “Be Thou My Vision.” Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. Celtic fiddle music.

I listen more and differently now to both music and words. Though it seems a little odd to put it this way, the pace of things hasn’t changed, but I listen more slowly. What was once background takes my whole attention. What I hear holds me, somehow, as though it has possibility and importance I never noticed before. As I’m finding food less and less appealing, I find increased nourishment in music and poetry.

Even the ambient natural sounds outside my window seem to summon my attention in new ways. I love the sound of the mourning dove and the chittering finches in the walnut tree. When it’s quiet I can hear the sound of the stream in the distance. That sound, in particular, water tumbling over rocks, soothes me when I’m troubled, and I think of Wendell Berry’s arresting line, “The impeded stream is the one that sings.” So much for me now is impeded, stopped, blocked—but the spirit in finds a pathway through my ears.

Being physically slowed opens my hearing. When I am not in pain, it seems to me I am able to listen more deeply, both to outer and to inner voices. I’ve never been one to claim that God “spoke to” me, though I’ve often felt guided and directed. But these days the veil thins between the conversations that keep me connected to life around me and the subtler callings and moments of what I might call awakening. I feel accompanied and addressed in new ways—not dramatic, or even describable, but comforting and challenging. As other capacities fail I feel called to listen, and to hold and be held in what I hear.

A Long Letting Go

At some point in our lives most of us will become caregivers. It is a vocation that can last for a few weeks of recovery time or for a long period of chronic illness or disability, and it will involve us intimately in others’ preparation for death. For us, too, it is preparation for a letting go that will draw upon our deepest spiritual resources in ways impossible fully to anticipate.

These reflections for caregivers focus on the season of death and the strenuous, challenging, life-changing work of accompanying a beloved friend or family member on the final stretch of his or her journey. They are rooted in my own experience of caring for family members who have died, keeping deathwatch with friends in times of loss, and serving as a hospice volunteer—humbling work that leaves me, after every visit and vigil, feeling privileged to be permitted into others’ sacred time and space. They are written primarily for those who believe in Christ and his promises, but may also serve others, from any faith community or from none, who happen upon them when life presents them with the task of caregiving. They are meant not as advice, nor as theological statement, but simply as a harvest of stories and experiences and personal observations that may provide some comfort, direction, hope, or consolation in a time when generosity, imagination, patience, skill, and love may be stretched in unprecedented ways.

A Common Lot

How shall I speak of doom, and ours in special,

but as of something altogether common?

—Donald Justice

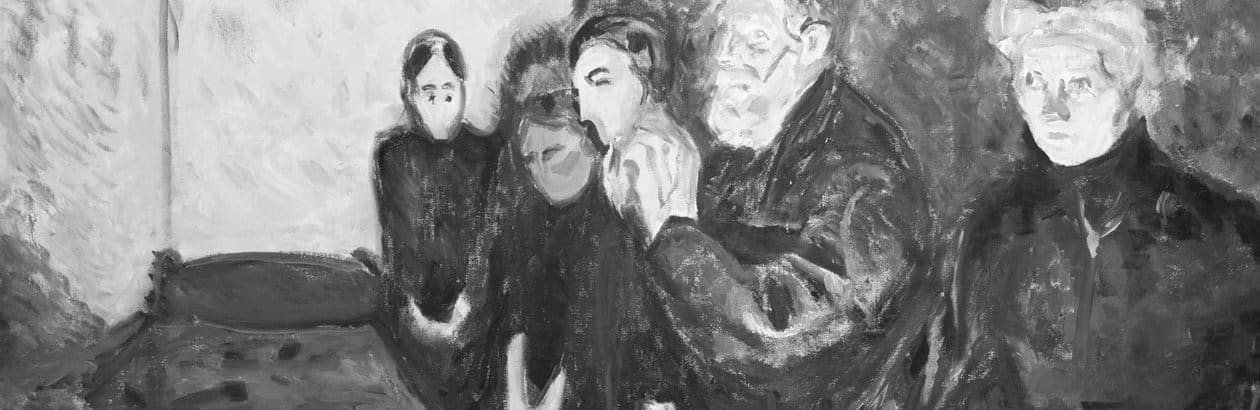

In the judgment scene of Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons when Sir Thomas More is about to be condemned, More interrupts the glowering judge who opens his thundering speech with the word “Death . . . ” and quietly finishes the sentence for him: “…comes to us all, my lord.” The reminder is startling in its simplicity. We all die. That truth deserves its own sentence before we add a “but” clause to object to the cruel, unjust, or untimely ways people die, or to protest from our deepest places of pain against the particular death that looms in our own lives with a shadow so heavy it feels impenetrable. Doom, as Donald Justice says, is our common lot. Perhaps the only comfort in that observation is the fact that we are not alone, though the feeling of aloneness can be intense and relentless sometimes. Insofar as the suffering of our own dying or the dying of persons we love so fiercely we can’t imagine life without them lies in the profound sense of isolation in our particular loss, placing ourselves in the wide communion of saints and sinners who have died, are dying, and will die can offer some consolation. We all get a turn.

To remind ourselves that death comes to us all, that it is our common lot, that it is the inevitable end of our earthly journey isn’t to insist that it is to be welcomed as a blessing. The biblical story line opens with the fall into death as the primal curse. Even if we believe that Christ has conquered death, that it has lost its sting, and that for some, like Paul, “to die is gain,” we can still rightly lament our losses.

At a memorial service some time ago where a friend’s life was being commemorated with much celebration a Jewish woman sitting next to me asked with some bewilderment, “Don’t Christians mourn?” We do. We must. We should. To mourn is to open an avenue of the particular grace and blessing promised in the Beatitudes. To mourn is to open ourselves to comfort, which is a unique dimension of love. To mourn is to make our sorrow hospitable to those who are willing to enter into it. It is possible to mourn generously by allowing our sorrow to awaken others to their own unmourned losses. It gives loss its due and allows our broken hearts the time they need to heal. Perhaps the Jewish custom of rending garments would be an apt and helpful “outward and visible sign” of mourning that needs to be entered into fully and bravely before it gives way to celebration.

No one can dictate exactly how much time that healing takes. Sorrow recurs in surprising ways, sometimes many years after loss. But the social dimension of loss—the fact that we are in it together and called together by it— gives our communities the right and obligation not only to support us in our mourning, but to call us back from it into the life that is left for us and help us learn to live it on new terms. In dying, as in living, “it is not right that man should be alone.” Most of us get a few chances to approach that threshold as witnesses before it is our turn to cross it. We know that the only way out is through. We know that new life awaits us, and that Love will bid us welcome. But this knowledge doesn’t, for most of us, entirely offset the very human rage and sadness that cry out against the incompletion and brokenness of the lives we live now. Our work is to accept the sorrow, to live it, to suffer it, and finally in humility to let it be drenched in the healing waters of love that comes to us from as many sources as we allow—great wells of it, great waves of it, and daily infusions from old friends and from strangers who may be angels sent to walk us through the valley of the shadow.

A Good Death

Let me die the death of the upright, and let my end be like his!”

—Num. 23:10

Both Catholic and Protestant prayer books have traditionally included prayers for a good death. One Catholic prayer includes petitions for “perfect sorrow, sincere contrition, remission of our sins, a worthy reception of the most holy Viaticum, the strengthening of the Sacrament of Extreme Unction, so that we may be able to stand with safety before the throne of the just but merciful Judge, our God and our Redeemer.” A similar one used in Anglican tradition includes petitions for “a full discharge from all his sins, who most earnestly begs it of Thee” and removal of “whatever is corrupt in him through human frailty, or by the snares of the enemy.” These forms emphasize repentance as a condition of receiving God’s great mercy. Some prayers and hymns offer a less contingent understanding of the divine mercy we die into, emphasizing that we are already completely safe in the arms of God, and that Christ’s redemptive will for us is far more spacious than our own imperfect acts of repentance. We see such a reminder in the 17th-century Dutch hymn that begins “There’s a wideness in God’s mercy like the wideness of the sea,” and later reminds us that “the love of God is broader than the measures of the mind.”

These petitions and assurances still inform our hopes for “a good death.” Naming some of those hopes may help us focus the prayers and the practical help we extend or ask for in the days and weeks we may be given to prepare for death.

Hope for forgiveness. This is a time to offer and receive forgiveness, releasing each other from lingering resentments. Forgiveness may involve naming old offenses or hurts, though sometimes naming them can reawaken them in ways that don’t help. A simple intention to release each other from anything that impairs the love between you, anything that might prolong guilt or resentment, and even from the need to understand the sources of old conflicts, can open your hearts to peace. I have often marveled at Cordelia’s words to King Lear who had rejected and disinherited her: when at the end of his life he asks her forgiveness, acknowledging how much cause she has to hate him, she immediately responds, “No cause. No cause.” Though by all rational measure she indeed has cause to despise him for his selfishness, vanity, and folly, in that moment her heart is so full of gratitude for reconciliation and so flooded with the love she has longed to give and receive, there is simply no room for resentment. That scene offers rich material for reflection on the way forgiveness transcends all scorekeeping.

Hope for completion: This is a time, as common counsel often suggests, to “take care of old business” and “set your affairs in order.” Still, one of the most consoling words I heard in a recent funeral service was that, though the stories of our lives on earth are completed at death, all deaths, even those that come at the end of a long, full life, leave some sense of incompletion. Perhaps that sense remains because we are created for eternity, and time belies what we most deeply know about ourselves—that our lives are not completed here. Nevertheless, longing for a “sense of an ending” is deeply human. So one practical gift that can help bring a “good death” is to help achieve the particular completions—small and large—that release the mind from earthly concerns. These often have to do with payment of debts, distribution of gifts and mementoes, recording untold stories, expressing hopes for children and grandchildren, destroying old letters or other documents that might cause pain, giving a final gift to church or charities. Each completion can open more space in mind and heart to rest more fully in peace.

Hope for what can happen only in solitude. Many who have been surrounded by attentive family and friends for weeks and months before death finally die—perhaps by choice— when no one is around. Some spiritual work requires solitude. Acceptance, trust in the processes at work in body and spirit, deep release of fear, and certainly rest require a time of inner and outer quiet. It is not unusual to hear a person who is dying admit the burden of having to comfort those he or she is leaving, having to meet the social expectations people bring to the bedside, having to endure not only one’s own pain, but the pain of others’ grief. Periods of solitude, even short ones, can be a gift and a relief for the dying—at least the offer of quiet time in which they may learn how to “let goods and kindred go, this mortal life also.”

There are other things to hope for at the time of death: a last conversation with an estranged friend; the encircling arms of a beloved who knows how to hold without hurting; music that opens the heart and speaks of heaven; stories whose endings invite us to imagine the heavenly banquet, the marriage feast, the home that awaits us at the end of this journey.