It is interesting that we often use the word “journey” when we refer to Lent, because Lent is a decidedly non-linear season for the church. We like to think of journeys as linear things, getting from point A to point B, going somewhere. But Lent isn’t about going somewhere. Lent is a time-out for the church—a season in which the church as a whole enters into an extended retreat. It’s not a time for doing anything or for going anywhere, but for spending time in the desert. This desert is not a geographical place of sand and sagebrush that you walk through to get to the other side. The Lenten desert is a place for meandering with God as we take the time to step away from what Paul metaphorically referred to as a race.

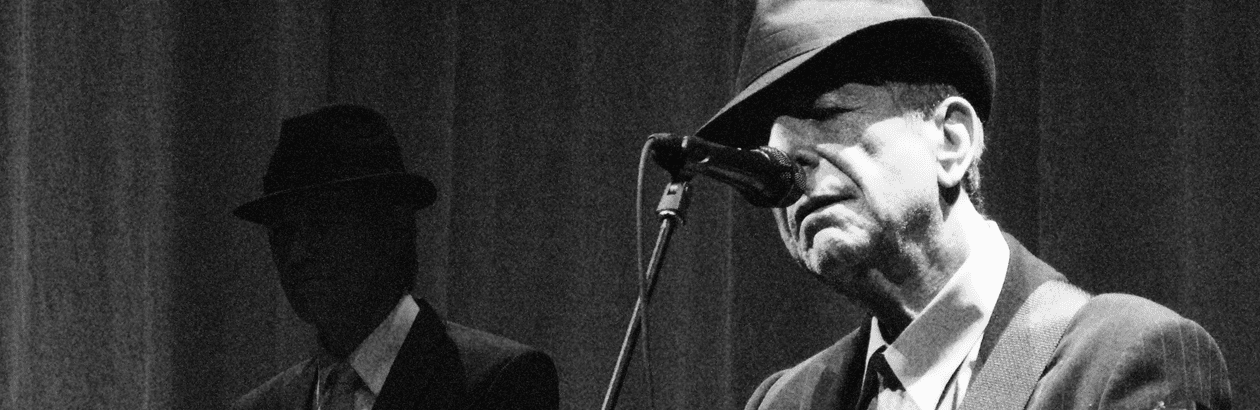

Every year I choose a piece of art, music, or literature to frame my personal rambling journey. This year I spent some Lenten time with Leonard Cohen and his new album of Old Ideas. This album, Cohen’s swan song, is about waiting for death, a decidedly Lenten theme. At 77, Cohen seems to have developed an elegiac acceptance of his physical and moral frailty. He stares into the abyss and patiently waits for a home without sorrows or burdens, a place he will go “without this costume that I wore.” With his gravelled-raw baritone and amelodic cadences, the troubadour with the “golden” voice offers a memento mori as his parting words.

The title of this album has a double meaning. These are songs about getting old, and the hard-won wisdom of a septuagenarian who has looked for love wherever he could find it—be it the momentary serenity of a Zen koan or the embrace of a woman he’d love to forget. But these are also old ideas because they are canonical. The themes of lust and regret, the willing flesh and the weakened spirit, are not new. Cohen has been shuffling these cards of love, faith, and moral languor for almost fifty years. But here these familiar ideas are imbued with the gravitas of a grave-bed confession.

The opening words of this album belong to God—a sardonic address to the self-styled sage who Cohen self-deprecatingly calls a “lazy bastard living in a suit.” Call it gallows humour, but dying is darkly comic. Still, God seems to enjoy spending time with Leonard, and Leonard in turn says, “Show me the place where you want your slave to go.” While Cohen tries to shake the prophetic image, he really does speak like a prophet—not as a willing messenger, but as an unlikely friend of God dragged to the mercy seat in irresistible chains by panting and scratched angels.

Like a biblical prophet of old, Cohen speaks words that are both apocalyptic and allusive. As the high priest of lyrical minimalism, he chooses his words with more circumspection than most of us take when choosing a spouse. Like nobody else, Cohen manages to create word pictures that are ambivalent but compelling, offering metaphors that are potent but unstrained—suggestive without closing the hermeneutic loop. Deeply steeped in biblical language, Cohen draws upon the scriptures, not to teach, but to exhume them as relics for a shared pilgrimage. Perhaps this is why I have always liked Cohen. He invites dialogue with the Christian story, drawing upon its promise of redemption in a way that allows me to transpose my story over his. In the time of Lent we wait together, Christian and Jew, for the Messiah to come. We wait for a time “when the filth of the butcher is washed in the blood of the lamb.”

Old Ideas, Cohen puts it, is a “manual for living with defeat,” a kind of ecclesiastical confession of a career ladies’ man seeking post-coital atonement. But for all the despair, Old Ideas is not a bleak album. Cohen’s sepulchral disclosures are counterbalanced by penitential hymns of healing and renewal. For Cohen, redemption is no esthetic escape from the fullness of life. Dropping his Buddhist robes, he rejects a Gnostic view of death as release from the weight of our carnal coil. In one of the album’s prettier moments, the song “Come Healing” offers a cry to the heavens for healing of both the spirit and the limb, the body and the mind. For a man who has made a career out of blurring the distinction between physical and spiritual ecstasy, such a prayer seems appropriate.

Jesus went into the desert for forty days and forty nights. During the season of Lent, Christians enter into a participation in Jesus, in his solitude, silence, and pain. Many Christians abstain from certain food and drink during this time as a way of recognizing that we observe this season as physical creatures, not as ghosts in the machine who contemplate from the distance. We enter into this season as people who still suffer—some emotionally, some physically, some to complete, as Paul said, the sufferings of Christ. And together with Cohen, we say, “Show me the place where the Word became a man, show me the place where the suffering began.”

To follow Cohen through these songs is a somatically reverential experience. Old Ideas is an album for the Lenten desert place—where there are few oases and the sun bakes our skin. It is a place where we learn to depend on, and wrestle with, God—and if we are like Cohen, we will hobble to the gates of mercy with a limp.