A

Although nuclear weapons have not been deployed since World War II, the world once again faces the serious possibility of a nuclear war. As Christians, it’s important to not only consider the power dynamics that a nuclear arsenal gives a country but also the anthropological presuppositions that are built into these kinds of weapons. In short, the use of nuclear arms assumes certain things about humanity—things contrary to the view of humanity that sustains Christian anthropology.

Tyler Wigg-Stevenson is an associate priest at St. Paul’s Bloor Street, an Anglican church in Toronto. Before that, he was for many years a full-time anti-nuclear activist, founding the Two Futures Project, a movement of Christians for nuclear threat reduction and the global abolition of nuclear weapons. He is also the author of several books, including Brand Jesus and The World Is Not Ours to Save. Managing editor Beca Bruder sat down with Wigg-Stevenson on Thursday March 10 to talk about the threat of the current conflict in Ukraine—and how Christians should respond.

—The editors

Beca Bruder: Tyler, can you give us an overview of where we stand in the current conflict in Ukraine? How much of USSR’s nuclear arsenal has Russia retained and maintained, and is there a real risk of entering into a nuclear war?

Tyler Wigg-Stevenson: Thank you so much for having me and for this conversation. I can comment on the Ukraine situation, but of course, there’s going to be a delay between this conversation and publication, and who knows what will happen tomorrow? Right now, though, Russia and Ukraine are in a conventional, non-nuclear conflict, with Russia using some pretty hideous tactics and conventional weapons, like thermobaric bombs. The US and NATO have used admirable restraint in not putting themselves in a position where they could be in direct conflict with Russia, because of the potential nuclear consequences of, say, a no-fly zone. A hot war between nuclear-armed states is an extraordinarily perilous thing.

Russia has about 6,000 nuclear weapons, of which 1,600 are deployed and ready for use. This is a significant reduction from their Cold War peak of about 40,000 weapons. The global peak in nuclear stockpiles was around 1986, when there were over 60,000 nuclear weapons worldwide. There was a significant dismantling of nuclear weapons after the Cold War, but that has slowed down in recent years. Despite these welcome reductions, the US and Russia still possess enough weapons—roughly 90 percent of the global arsenal—to kill almost every living thing on the planet. Other than the US and Russia, there are seven other nuclear powers: China, Britain, France, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea.

I’ve been working on this issue for over twenty years, and I’ve never been as realistically frightened as I am right now. I wake up at night to see if the world’s still there. I wouldn’t put money on a nuclear war beginning, but you can write a scenario where this turns into nuclear war without resorting to science fiction or outlandish situations. In the heat of war, mistakes happen. And people react in different ways that you can’t expect. It’s entirely possible to get drawn into a rapid escalation.

BB: Russia has been dropping high-precision strikes all over Ukraine over the last two weeks already. We’ve seen terrible images: buildings, schools, hospitals in shambles. It’s horrible and deplorable as it is. Yet there’s a difference between conventional bombing and nuclear bombs. What makes nuclear war unique?

TWS: Some of the biggest conventional bombs have massive destructive capacities. But what makes a nuclear weapon unique is that it’s categorically indiscriminate. You cannot use a nuclear weapon in a way that distinguishes between combatant and non-combatant. In fact, the odds are non-combatants are going to bear the brunt of it. That differs significantly from a bullet in a rifle, or even horrible weapons of war that can—at least technically—be used simply to fight between armies.

This gets at the very heart of what in secular discourse would be the “law of war”—this loose corpus of treaties and laws and historical norms around what’s legitimate or not in war—which in turn owes a significant debt to the Christian just-war tradition. At the heart of this tradition is the capacity to distinguish between combatant and non-combatant. This distinction is founded on a sense of the human person made in the image of God, which means that all killing must be taken extremely seriously.

Now, it’s possible to construct a scenario in your mind where you use a smaller nuclear weapon on a battalion of the enemy, somewhere in the middle of nowhere, that doesn’t kill non-combatants. But I think that’s just in the fever dreams of some ethicists. In reality, the weight of the nuclear taboo—that they haven’t been used in war since World War II—is such that to use a nuclear weapon is to invite a process of escalation that results in the mass death of non-combatants.

This is why nuclear weapons violate the just-war criterion of “macro-proportionality”: Is the use of a weapon in war proportional to the conflict at hand? I don’t think anyone can make the case that the use of a nuclear weapon is proportional to any conflict, given the consequences of breaking the taboo of nuclear use.

The impossibility of using nuclear weapons in ways constrained by justice means, in my view, that nuclear weapons should be considered malum in se—evil in itself. This is a distinct category of the just-war tradition, which includes other weapons like chemical and biological weapons, or the use of rape as a weapon in war. Such things are incommensurate with the attainment of peace, which the Christian tradition—at least the non-pacifist strands of it—would say must be the governing purpose of war, as awful as it is.

Now, as we’re seeing in the Russian invasion, conventional weapons can also be used in ways that violate just-war traditions—for example, the systemic Russian bombing of hospitals with conventional weapons. That’s to be condemned without qualification. But nuclear weapons do this essentially, they are inherently unjust, and that’s what makes them distinct.

BB: I want to zoom in on the human aspect. What does our vision of theological anthropology say about humanity, particularly humanity’s worth?

TWS: I can’t speak to what is the Christian theological anthropology. But I can speak to some themes that would be largely uncontroversial, especially with regard to the way we would think about nuclear weapons. The constraints of the just-war tradition are founded on a sense of the significance of the human person. This goes straight back to the covenant that God makes with Noah in the wake of the flood. The image-bearing essence of the human person is invoked by God in Genesis 9 to say that because the human person is made in his image, the one who sheds human blood will have their blood shed. That human life, made in the image of God, is not to be taken lightly.

In war, we get used to all these statistics. People die by the thousands. War entails killing on such a scale that we are morally incapable of dealing with it in our usual interpersonal capacities. If you suffered a loss in your own life, that’s an overwhelming tragedy. But the casualties of war so overflow our capacities for moral apprehension that we become numb. In my work talking with people about nuclear weapons, there’s an almost intoxicating effect of the number of zeros in the projected casualties of nuclear weapons. It’s so vast that you lose sight of the human beings that are killed by a nuclear weapon, simply because you can’t take in that much. We just can’t. That scale masks the truth in a way that is demonic. That’s why I think it can be so challenging and so difficult to marshal opposition to these things, because no one can actually grapple with the reality of a nuclear weapon.

nuclear II by László Moholy-Nagy, 1946.

BB: How do nuclear weapons change the perspective of the value of human life?

TWS: It’s interesting how often eschatological terms like “apocalypse” or “Armageddon” come up when talking about nuclear war. In the Bible, the book of Revelation is the thing you don’t have to think past. I don’t spend my time worrying about what happens after Revelation 22. It’s the beyond, right? God has pronounced judgment. The sifting has happened. Whatever God is going to do, it’s done, and it’s none of my business anyway. I have an utter lack of agency to affect those events. Nuclear weapons hold a similar place in the political imagination of people. They’re the thing that you don’t have to think past, because of the devastation they promise. It’s so vast that it creates a moral apathy in people, a reminder of their own lack of agency on that scale.

BB: Our methods of war have evolved from up-close conflict to distant engagement. Always seeking more distance from your opponent and more power from your weapon. How do weapons of mass destruction redefine humanity’s relationship with their enemies?

TWS: Nuclear weapons don’t intersect most people’s lives at all, which is the challenge. That’s reinforced by the iconography of nuclear weapons. If I asked you what image you associate with nuclear weapons, what’s the first thing that comes to your mind?

BB: The mushroom cloud.

TWS: Right. The mushroom-cloud image is a photograph taken miles and miles away from the event at hand. The people affected, the image bearers of God, are lost to the distance. Think of the photographs that have made a difference in public opinion, like the iconic image of the girl who’s a victim of napalm in the Vietnam War, running down the road. Or Aylan Kurdi, the Syrian refugee boy who washed up on the shore. Or the photo published on the front page of the New York Times of a Ukrainian mother killed with her children. These pictures, by being smaller, actually become bigger. Those images are nearly impossible with a nuclear weapon—not only because there hasn’t been a nuclear explosion on a population since World War II, but also because even if there were one it’s very dangerous to go into a region that’s been bombed by a nuclear weapon.

The distancing effect pushes these things out of our consciousness. It’s easy to talk about what they do physically speaking, chemically speaking. Temperature, blast effect. But in truth, it’s very difficult for us to apprehend what they do on a human level. And the scale protects us from having to grapple with the humanity of our enemies. These are weapons built for extermination—of cities, peoples, countries.

BB: The normal human tendency is to either display “let’s save the world” bravado or to let fear and feelings of insignificance make us feel like there’s nothing we can do. How can we take an approach that’s small enough to be practical and large enough to respect human value instead?

TWS: For many people in the West, this seems to be their first real experience of war. That’s absurd, given that the US has been in a war almost continuously for two decades, but there it is. There are wars constantly going on with people who don’t look like Ukrainians, so the fact that this is some people’s first experience of war is influenced by questions of race and imperialism and colonialism—but that’s a separate issue.

Anyway, now people are being confronted with the fact that in war, there’s nothing that you can do, literally nothing. That hurts, because the privileged West—which I sit at the very top of—is accustomed to having some control or agency, even if it’s just on social media. Even if you can’t do anything else, you can craft a morally pure Twitter thread. But when the bullets start flying, a war is going to be prosecuted, and it will come to an end when the sides that are fighting it want it to come to an end, or when one wins. That’s a hideously unnerving place to be for people who have largely lived boring lives full of agency.

People want to know what to do. How do I recover some agency in the face of this? To try and support Ukrainian refugees is probably about as good as it gets for most of us. But this should also lead us into the theological apprehension that we live in a world we do not make. The illusion of modernity is that the world is ours as individuals to shape and make, and that’s simply a lie. We are all born into conditions we didn’t manufacture. We will contribute to the conditions that we pass on to the next generation, but largely in ways that are not strictly determined by our own intentions. The next generation will deal with the same thing. And that’s what it is to be alive. That’s what it is to be a human person before God. War is never to be celebrated, but we can acknowledge that war brings home our finitude and weakness.

So what you do is, you love. You love even when it’s futile, and you love in the best ways that you possibly can—whether or not that means military intervention. The question we’re all wrestling with here is how do you love? You can’t bring about peace on earth and goodwill to all. But you can, in your own way, be faithful to the God who calls us to seek his kingdom, who offers salvation in Jesus Christ. Unfortunately, sometimes loving faithfully will mean being very sad.

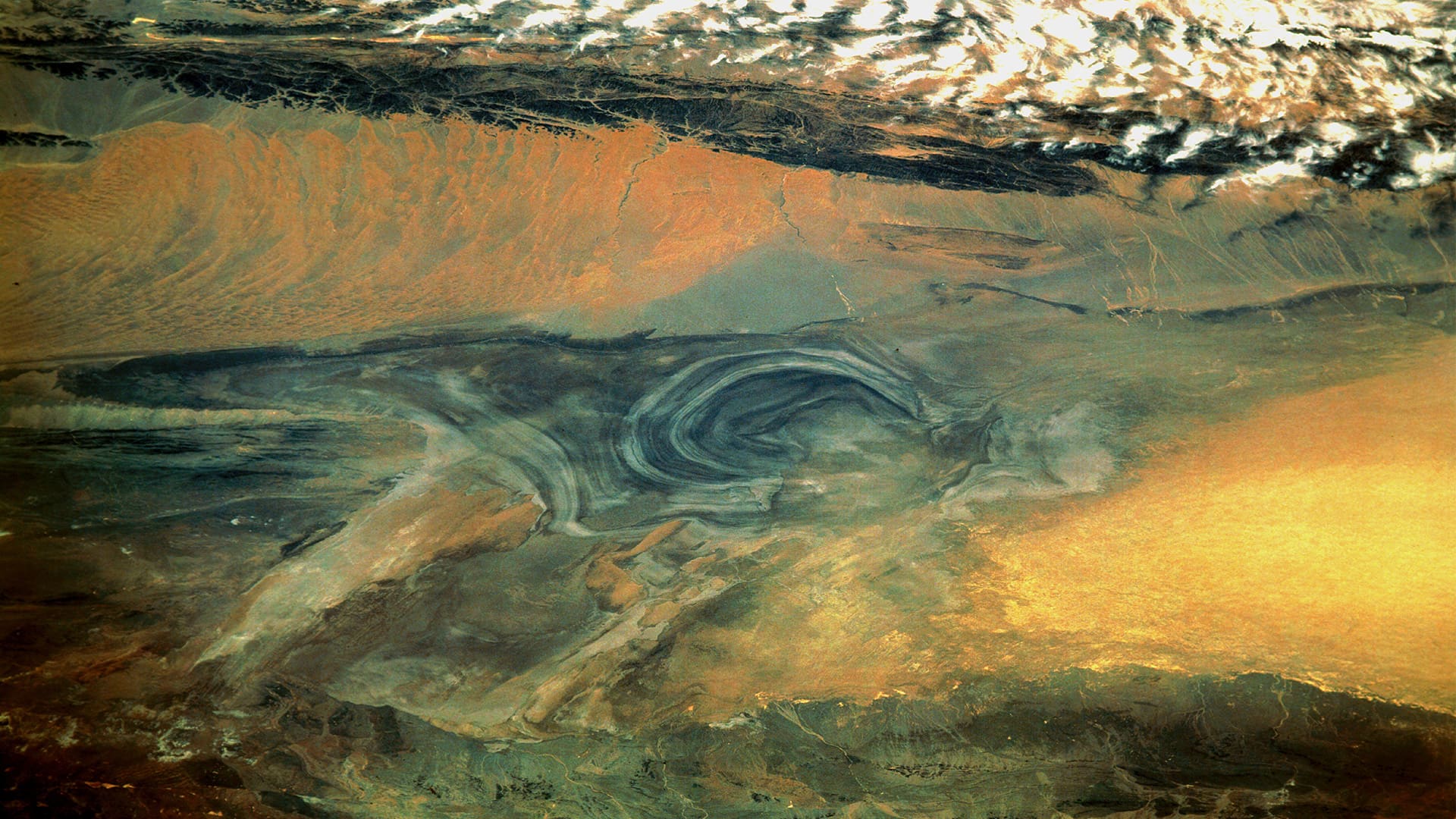

Licorne nuclear test on Fangataufa, 1970.

BB: We have this perspective that we are to love. We are to engage with people in a way that honours their worth as image bearers of God. Yet we still live in a world where we’re watching this disaster that is taking the complete opposite approach. As much as we want to influence it, there’s nothing we can do to stop it. How does a vision for human anthropology that values lives above nations, power, or fame help the civilian who’s watching this conflict think through nuclear issues, pray about them, and engage in conversation with others?

TWS: Your point about prayer is of immense importance, because it’s an acknowledgement of our dependence on God. We just celebrated this with Ash Wednesday: We are dust quickened by the Spirit, and when the Spirit is withdrawn, we will be dust again, so we hope in the resurrection.

I want to do an obnoxious academic thing, though, and pick at the terms in the question that you just posed, because I think the formulation of valuing lives above nations or vice versa is a bit of a false dichotomy. Nations can and should serve human life. Nations have a scriptural ontology. They have a reality in the word of God that we hear over and over again: the nations of the earth, the families of the earth.

The origin of the word “nation” is etymologically rooted in the Latin for birth. The nation is our family, which is not how we use nation today, but that’s where it comes from. It’s probably more in line with our concepts of ethnicity and culture today. And these are not bad things. The world is not just billions of individuals walking around independently. Yes, we also have this vision of individuals before God: every knee shall bow, every tongue confess. These are individual tongues, individual knees. But we’re also people who take our shape within a national, familial, cultural context. In Revelation, we see that the kings of the earth are going to bring the wealth of the nations before God.

I say that because that point can give us a sense of why it’s important for Ukrainians to feel Ukrainian or Russians to feel Russian. These aren’t static categories; families, cultures, nations can mix, which is beautiful. And of course these categories can be spun out into nationalistic parodies and caricatures that are antichrist, imagining the supremacy of one nation or family or culture over any other. Think white Christian nationalism, or this Russky Mir, “Russian world” doctrine that seems to be animating Putin. But exploding the categories out helps us to see that we have this created essence of being part of a family. In that respect, nations—communities, peoples, cultures—are to be treasured.

Yet these legitimate bonds of family and culture are also inevitably distorted by our sinful capacity to kill, to order human life through coercive power. That capacity is still subject to the demands of the justice of God. This is how I would read Romans 13, “All authorities created by God and implemented by God for good.” It gives us a sense of how human life and the nation are called to serve each other—and in contrast, the ways in which the coercive powers of the state so easily come under what I have no qualms about calling demonic influence, in terms of their diabolical application in ways that utterly thwart justice and destroy human life. This gives us grounds for condemning what Russia is doing. And it also gives us some ways of thinking about the peace that we want to construct.

If we value the lives of individuals within nations, that points directly to a world without nuclear weapons. That’s not imminently attainable, but it provides the morning star guiding what will inevitably be long and frustrating work on the far side of this invasion—assuming, God willing, that we get through it without a nuclear war.

BB: It also gives Christians the perspective that there is a just God who is sovereign over the world. We can trust that as much as there is power for destruction in this world, even as big as a nuclear weapon, nothing is outside the control of God.

TWS: I would argue that in church circles in the West, the sovereignty of God is invoked as a way of making people feel better. But it doesn’t make me feel much better because God has been sovereign throughout human history, and it has been tragic beyond imagination. God was sovereign over World War II, when millions of people were killed. God was sovereign over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In other words, God being sovereign does not mean that we will not encounter tragedy that is almost beyond our capacity to bear. That’s a very hard thing, I think, for Western Christians to reconcile. We want to be cheerful about things. But I don’t think there’s much historical ground for that. What we’re encountering right now is the existentially unnerving fact that the last seventy years, the postwar era, are a historical anomaly rather than the rule. This is not a very cheery note to end on, but I’m trying to learn what it means to live and be sad and still be faithful.