T

The year 1980 was a big one for me. I finished primary school and started secondary school, and I moved from Cub Scouts to Scouts. The first transition was bloodless, bureaucratic. There were no ceremonies that I can recall, either on leaving one institution or joining the next. (I was in the UK, where the only place from which you “graduate” is college.)

But the evening of my transformation from “Cub” to “Scout” remains vivid in my memory. The ceremony took place in a half-century-old wooden village hall. The Cub Pack was lined up at one end of the hall, the Scout Troop at the other. Most of the space in between was taken up with a large parachute, apparently left over from World War II, being held by some adult volunteers along each side.

When my turn came, I faced the Cubs, saluted, and went under the parachute as it was shaken above me. It was disorienting. I can remember the musty smell, the odd changes in light, and the sensation of the chute coming down repeatedly on my crouched form. Not scary exactly, but weird. We had been told to put our new Scout shirts underneath our Cub sweaters, and under the white waves I changed my clothing. Emerging at the other end of the hall, I was greeted by cheers from the Scouts and their leaders. I made the Scout sign and solemnly recited the Scout promise, which I had been practicing all week, to “Akela,” the Group Scout Leader, in front of various flags. I was then invested with a Scout scarf, along with a red woggle showing which patrol I was to join. I lined up neatly with Red Patrol, after being welcomed by the older boy who was to be my patrol leader.

The whole thing cannot have lasted more than five minutes. Lord Baden-Powell, the founder of scouting, said that “the investiture of a Scout should be a short, simple, but solemn ceremony.” Baden-Powell chose the archaic term “investiture” deliberately. Being “vested” means literally to “take on the clothes” of a new role. It is the term used to describe knighthood ceremonies. This is not a coincidence. Baden-Powell said that “one aim of the Boy Scouts scheme is to revive amongst us, if possible, some of the rules of the knights of old.”

This was, of course, a rite of passage. The three critical elements of such a rite, according to the classic scholarly work in Arnold van Gennep’s 1909 book Les Rites de Passage, are, first, separation from the old world, often marked by removal of clothing, physical location, or similar; second, a “liminal” or in-between phase, outside the normal world and often involving some kind of test; and third, incorporation into the new identity or role, often by new clothes, the taking of oaths, or public recognition.

I am quite sure none of the Scout leaders present had read van Gennep’s work. But it didn’t matter. The basic structure is outlined in the training of leaders, with plenty of room for local variation; there’s no rule that the ceremony will involve a parachute, for example. The key point is that all three of the basic elements were present that evening, and that the atmosphere—the ethos—of the ceremony was deeply serious. When I became a Scout leader myself three decades later, I was a stickler for the rituals and rites of the movement: investitures, badges, promises, patrols, songs, salutes—the works.

It wasn’t the only rite of passage I went through. In Scouts I remember the night I spent camping in the woods alone to pass an important milestone. My confirmation into the Church of England, even against my protests, nonetheless left me somehow transformed. Entering the “Sixth Form” too: in my school, the sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds wore a different uniform and, crucially, had our own common room.

I imagine most of us, especially most men, have similar stories. The process of moving from childhood to adulthood is not one that happens simply with the passage of time. Sometimes we describe these rites of passage as “marking” a key transition, but that’s not true, at least if they’re done right. As religion scholar Connor Wood points out, “Initiation rites don’t ‘mark’ the change from boy- or girlhood to adulthood, because there’s no clear physiological change to mark (especially for boys, who don’t have a first menstrual period). Instead, they cause the transition, which is cultural in nature, not biological or hormonal.”

That was certainly my experience. When I emerged from the parachute, and took Communion, and walked out of the wood in the dawn, I was, in some imprecise but profound way, a different person. As Wood notes, there is a difference here between the sexes. I called him up to confirm my impression of his work. He told me, “Yes, boys need that cultural input more than girls.”

Modern scholars tend to gloss over the fact that in traditional societies the rites of passage for boys and men are a much bigger deal than for women and girls. Most societies have had initiation rites for boys, not so for girls. But there’s a good reason for that, and it goes beyond patriarchy. The transition from girl to woman is a much more clearly embodied experience than from boy to man. Women know, even if subconsciously, that the tribe needs them. Wombs are extremely precious. There is a reason every thoughtful sci-fi story involving the creation of a new human colony makes the point that many more women than men are needed for the enterprise.

But we have to form men out of boys. Men are made, not grown. That requires structure as well as instruction; it requires rituals and rites. And these can be provided only by institutions. As anthropologist Margaret Mead writes, “The human family depends on the social invention that will make each generation of males want to nurture women and children.”

We have to form men out of boys. Men are made, not grown. That requires structure as well as instruction; it requires rituals and rites. And these can be provided only by institutions.

Recent neuroscience adds some important nuance here. The construction of mature, contributory masculinity has some biological basis after all, especially when it comes to fatherhood. I have been thrilled to learn, for example, that dads get a spike in oxytocin, the bonding or so-called love hormone, from interacting with their children, just in a different way from mothers. Moms get their hit from cuddling with their children. Dads get theirs from throwing them in the air and, importantly, catching them on the way down.

The huge sex difference in risk-taking, too, has both a biological and a social basis—one reason, perhaps, that many rites of passage involve the demonstration of courage. In 1962, Mead worried about the implications of the decline in mass warfare (a decline that, to be clear, she welcomed) for men, urging, “It is essential that the tasks of the future should be so organized that as dying for one’s country becomes unfeasible, taking risks for that which is loved may still be possible.”

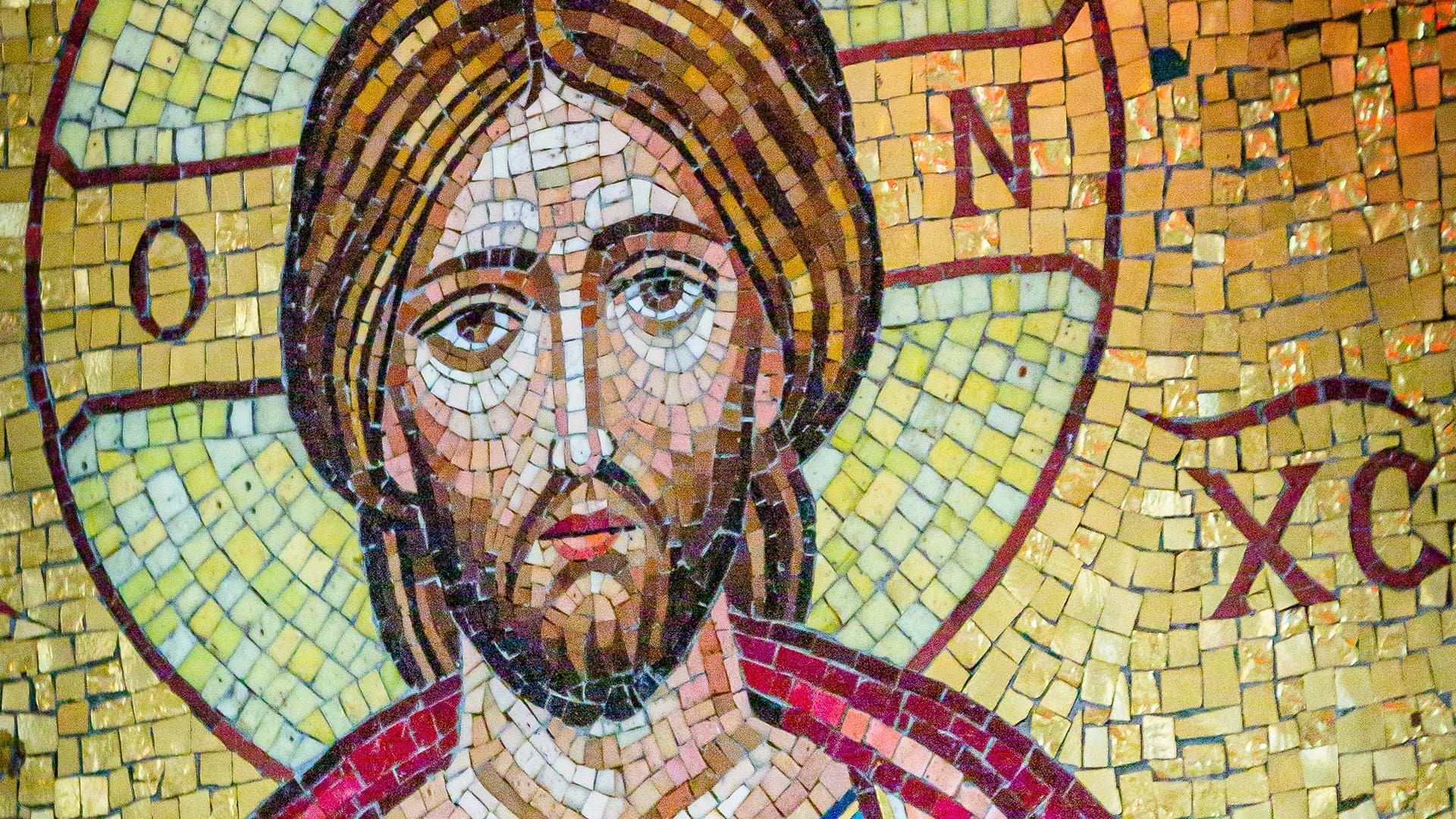

Institutions provide the scaffolding within which both rites of passage and ongoing moral formation through rituals can take place. This is historically a role played by organized religion, and one of the most intriguing social trends of recent years is the possibly greater religiosity of young men than young women, a reversal of the historic gender gap.

In the UK, the share of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds identifying as religious increased fourfold, from 4 percent to 16 percent, between 2018 and 2024, according to a YouGov survey conducted for the Bible Society, with more men than women heading for the sanctuary. In the US, a large 2023 survey by the Survey Center on American Life found that 39 percent of Gen Z women self-describe as religiously unaffiliated, compared to 34 percent of their male peers. There is also some evidence that young men are being particularly drawn to more traditional denominations. A survey of twenty Orthodox churches found a surge in male converts from 2020 to 2023, with most in their twenties and thirties.

It is important not to overstate these trends. The big picture seems to be that young women are simply secularizing faster than young men. But there’s certainly enough here to be interesting. In my own recent experience attending a Latin Mass at the Basilica of the Immaculate Conception in Denver, Colorado, and a Divine Liturgy at St. Elias Orthodox Church in Austin, Texas, both were brimful of young men. When I talked to those who were converts or would-be converts, the clear sense I got was of young men looking for structure, meaning-making, and formation. The intensely ritualistic nature of the more traditional services seems to be part of the appeal. Theologian Zachary Porcu (himself a convert to Orthodoxy, as am I) suggests that “Orthodoxy is a call to adventure because it asks you to fast, to pray, to do all these physical things, to do this journey of self-improvement that I think can be contextualized into a very masculine, appealing dimension.” A similar impulse almost certainly lies behind the men searching for guidance online. All the videos about morning routines, fitness, and discipline speak to a hunger not for more freedom but for moral formation.

Rituals are an ancient social technology for learning self-control. Indeed, there is strong evidence that participating in religious rituals has a greater influence on self-control over the long run than religious belief. It’s the doing, not the believing, that seems to matter most on this front. Rituals, according to anthropologist Roy Rappaport, are humanity’s “basic social act” and require institutional support. This is one way in which institutions fulfill their role as mechanisms for social learning, especially across generations. They are, to paraphrase Mary Douglas, how we remember what we would otherwise forget.

And throughout human history one of the most important lessons has been how to be a man. As Wood told me, “Being a man is more of a role, more of a social construct, than being a woman is.” Yet the question of how to be a man too often goes unanswered now. Some might even argue that it does not require an answer. The results of a generation of men coming of age without one, however, have not been salutary; millions of young men feel lost. A much-shared essay by an anonymous twentysomething woman published on Scott Alexander’s blog Astral Codex Ten in August 2025 with the title “Dating Men in the Bay Area” was, despite the clickbaity title, a thoughtful meditation on the social construction of masculinity.

“Gone are the days of carefully defined rituals, initiations, expectations, and stepping stones,” she writes. “Now young men are expected to figure out the map through a bewildering mixture of movies, TV, social media, video games, books, news articles, and school.” She points out that while the map to womanhood has been redrawn, it has been retained because “being a mother is still a respected role in society.” By contrast, men have been left with something “scrawled by a half-blind cartographer tripping on acid.” I think she is exactly right.

To some extent we are playing catch-up here. Some of our most formative years are in our teens. So the life stage we now call adolescence is when most of the work of formation must be done. This is when we become capable of reproduction, and when our hormones start yelling at us to get the job done. It is when we are learning the skills to navigate adult life, especially managing relationships. It is when we learn, above all, how to regulate and control ourselves, both for our own good and for the good of broader society. We now know as a matter of science what our ancestors knew intuitively about the best timing for rites of passage: adolescence is a period of extraordinary brain plasticity, when we are “experience expectant,” primed for cues and stimuli from the world around us about what it means to grow up and how to show ourselves worthy of inclusion in the tribe.

One reason institutionalized rituals and rites of passage are socially adaptive is that they signal an ability to defer gratification, exercise self-control, endure discomfort or uncertainty, and dilute self. These are all, of course, highly desirable traits in any society that wants to live together well and prosper into the future.

If one stereotype about young men today is that they are becoming a movement of misogynists, another is that they are apathetic and absorbed either in themselves or in their computer screens. While both stereotypes speak to worrying trends, the reality is more complicated. Many young men today have recognized that they are not sufficiently formed, and they are trying to do something about that. This search is to be celebrated. But it should also prompt us to ask some hard questions about how so many young men have ended up here.

Young men are not shirking responsibility; they are searching for it. They don’t want fewer obligations; they want more.

With Robert Putnam, the eminent social scientist and author of Bowling Alone, I recently published an essay in the New York Times on the need for a more robust civic response to the genuine challenges of our boys and men. The most-favoured comment among Times readers captured the cultural reflex: “Stop whining and pull yourselves together—nothing is stopping you except the infernal screens.” In some way this is what many young men are indeed trying to do. But they can’t do it alone. Blaming them for their plight is counterproductive.

One of the most successful social policy interventions I’ve ever seen is the Becoming A Man (BAM) program from Chicago, which reduced crime rates among young black men by almost 50 percent and increased high school graduation rates by almost 19 percent. Now in other cities, it is a group-based mentoring initiative focused on values such as integrity and accountability and on learning how to understand and control impulses and emotions. BAM works because it builds community, unapologetically promotes virtue, is designed for boys, and is led by men.

Young men are not shirking responsibility; they are searching for it. They don’t want fewer obligations; they want more. They are stumbling for the sense of place and belonging that our mainstream institutions have failed to provide them. The civic organizations that have done so much of this work have mostly moved away from a specific mission to prepare boys for manhood. Boy Scouts no longer exists, having been replaced by Scouting America, now that the organization admits girls. (Girl Scouts remains single-sex.) The YMCA now serves more young women than young men. In many cases, as Putnam and I show, this is because of a lack of male volunteers.

Of course, institutions can stifle and constrain and at worst be oppressive. This is a message that liberals have successfully communicated. But that does not mean human societies, for all their modernity and rationality, have somehow leapt free of the need for institutions. John Stuart Mill, one of the founding fathers of modern liberalism, insisted that the institutions of marriage, family, workplace, trade union, school, army, university, civic association, and democracy were all “schools of character.” Institutions are judged not simply by their technocratic efficiency but by their ethical impact. “The spirit of an institution, the impression it makes on the mind of the citizen,” Mill writes, “is one of the most important parts of its operation.”

The animating spirit of Scouting certainly made an impression on my mind almost half a century ago. Liberal societies, as Mill knew as well as any, are no less demanding of individual formation than the most ancient hunter-gatherer tribes. The social scaffolds of institutions can be seen as a cage to trap us. But they can also be seen as a trellis on which we grow. And we need them now, above all, to help form our boys into young men—even, dare we hope, into gentlemen.