I

I started writing this essay eight years ago, about a year after my third child was born. The opening scene deploys a voice I know as mine, yet shows its age and, more significantly, its shame. The shame emerges from an unresolved conflict within me, as I find myself crushed between duelling idealisms about motherhood and a life of the mind. I wanted to convince an imagined reader that, as a mother, I was authentically engaged in a serious human task that necessitated, among other things, my intellect.

Grasping at the straws of many straw men, I narrow my attention on a Dominican Thomist, A.G. Sertillanges, who lived from 1863 to 1948. Dead and distant to me, this man is safe: someone who will not and cannot reply.

I first learned of A.G. Sertillanges through Twitter, which was then and is still now an embarrassing narrative detail. Someone posted one of his better-known quotes—a shiny gold nugget in that once vibrant riverbed—from the preface of Sertillanges’s classic text, The Intellectual Life: “‘Do you want to do intellectual work? Begin by creating a zone of silence . . .’ —#Sertillanges.” Something like that.

I didn’t know how to pronounce that name. It sounded ancient, a pre-Jesus, Greek-philosopher fairy-tale figure. I started pronouncing this new quotable wise man “Surt-il-LAN-gees,” and imagined him as a rhyming contemporary of Diogenes the Cynic, peddling zones of silence for whomever was wise enough to procure them.

Of course, at the time, as a mother of a nursing infant and two elementary-aged children, I was drawn first and instinctively to the “zone of silence,” and longings to “do intellectual work.” I could not imagine implementing the costly disciplines that a real intellectual life would require, nor could I stomach the known and unknown costs in the midst of the intensity of young motherhood. (Indeed, like Esau for lentils, I would have traded my birthright for a solid length of contiguous sleep.)

Nevertheless, I asked for the book for Christmas. Bouncing my four-month-old, third-born baby on my lap, I ripped the wrapping paper from the shiny red paperback copy of The Intellectual Life, and read out that same call and my response with gusto to my gathered family, an encore of that soul-saving quote I had first read on Twitter: “Do you want to do intellectual work?” Oh Surt-il-LAN-gees, I do! I do! That Christmas morning, I clutched that book as a young child holds the deteriorating threads of a lovey blanket worn by years of anxious rubbing.

Like Jacob for Rachel, I laboured at these paragraphs above. Many kind friends and even a few strangers scattered across various countries read versions of these and other paragraphs over the years, offering their feedback, dancing on the edges of wounds.

I read Sertillanges’s The Intellectual Life many times, hoping that one of the passes would transfigure me. Published originally in 1921, reissued in 1992, the book sets out the norms by which one cultivates a truly intellectual life, “its spirit, conditions, and methods.” It is often commended to young scholars and others moving toward intellectually inclined professions, including those in pastoral work.

But with each reread, found myself growing more like a surly teenager, fighting with an imagined father figure. The text hurt. I began to argue in the margins with poor Fr. A.G., OP, who inhabited an altogether different world and time. I corrected and expanded the book’s index to include words related to women, childbirth, children, housework, and the home. These absences in the intellectual’s habitus did not just infuriate me; they terrified me.

A mother is not at all whom Sertillanges had in mind when he penned his text. The reader’s a he, and that’s that. It’s not hard to make the mental adjustments. As Sertillanges’s English translator in her note modestly advises: “Everyone whose business it is to use his mind (or her mind, for his can be common gender) in any kind of work . . . will find rich suggestion in it.” Indeed, she’s right.

It’s not that women aren’t present to the world and labours of the intellectual, because they are very much there. She is at his side, mending, knitting, busy with women’s work and even buoying the intellectual’s spirit by her own fervent, non-intellectual productivity. Children are present as well; one, at least, can overhear them at a distance until they are properly shooed away to secure the zone of silence and minded by other (non-)minds. Children provide the intellectual with immense joy and brief refreshment, and model the kind of inquisitive, wonder-filled thought that cools the mind and calms the soul.

My thoughts then turn even more defensive and sprawling, tilting at every windmill I see. I get tangled in red string, trying to loop around all the essential pins in my growing theory of everything. I would write myself into exhausted corners, ever flailing, with some versions of the essay extending for many pages of growing wilderness.

Fear prevented me from writing or thinking my way out of my inner conflict. What I feared most was that my own labours among little people in the home had no recognition in the record of knowledge. It was terrifying to consider that for all the mind I was giving as a mother to particular others, my labours at knowing—coming to understand that my infant’s delicate blink was a subtle cue of fatigue; enjoying but not interrupting the storied chatter of his toddler play—would fall under the shadow of that which is assumed, taken for granted, and so often devalued.

I see this younger me with tenderness, recognizing that she was on to something. For the thesis has been reliably stable and simple: Mothering is intellectually demanding work. I long insisted on saying “mothering,” and not “parenting,” because caring for one’s young and the home in which loved ones dwell has so long been the provenance of women. But I have since relaxed my grip on this. For one thing, I have known too many women and men who have yielded freely to the demanding givenness of human life, characterized by long, loving attention of other particular human beings in the wider world. These qualities belong to no single gender, nor solely to people with biological progeny. And as I have learned to attend to the deeper character of relentless care, my awareness of the richness of what counts as intelligent labour has grown.

It took me years—long, slow years—to articulate this thesis for myself. Those earliest days of new mothering I experienced as a personal earthquake, a great, long shaking of the self. Like all new parents, my husband and I had to climb a steep learning curve with this new particular other, a gutsy little stranger who entered the world knowing more than she could tell. As a young family, ready and not, we were embarked on one of the great, humbling tasks of home, one that demanded all: body, mind, and soul. It was as much an unmaking as a making. We were learning her, of course, but we were also coming to see and know the world differently as a result of our becoming people capable of learning and attending to another life. Our apprehension of reality had changed because she was now in it, and every little thing mattered.

Mothering is intellectually demanding work.

Yet in those very early days, I knew of few resources that recognized that the difficult work I was doing as a mother was intelligent, as integrally connected to the fabric of human life and society as any other venture that demands our best efforts. Most of the mothering and homemaking discourse that I was aware of then framed both as essentially mindless, or as problems meriting technical solutions of advice and “parenting hacks.” Child care was honoured in the way one might honour garbage collectors. (Thank God somebody does it! Thank God it’s not me.) In some circles, regrettably often clothed in the language of faith, motherhood’s nearly self-obliterating sacrifices were lauded. In others, the work of child-rearing was a kind of character-building hamster wheel: “all joy and no fun,” full of “mind-numbing” boredom, isolation, and mindlessly frenetic busyness. (PTA meetings! Volunteering! Birthday parties! Valentines! Shuttling minivans!) The visions of mothering ran the gambit from being an all-consuming fire requiring an utter abnegation of the self, to a profound form of selfing, which, if one is sufficiently skilled in executive functioning, might also be monetized profitably. Whether it was the mommy blogosphere then or #tradwives now, social media has both distilled and divided the discourse into ever purer forms.

But some bright gems revealed the degradation for what it was. My parents gave me a copy of Kathleen Norris’s The Quotidian Mysteries just a few months after my first child was born, and it helped—a lot. Her insights were not romantic, nor two-dimensional, and absolutely not condescending. Norris’s 1998 Madeleva Lecture that became the book recognizes the value of the daily repetitions involved in caring for human life, so often performed by women. She describes knowing early on that she was not likely destined for motherhood, but writes with a keenly attentive eye to the necessary, ordinary “little things” to which God gives attention too. Norris warns that “our culture’s ideal self, especially the accomplished, professional self, rises above” these embodied necessities of care, which education is supposed to free us from having to perform ourselves.

Jennifer Banks’s more recently published, intellectually luminous Natality: Toward a Philosophy of Birth comes just as close to the kind of articulated knowing for which I then hungered. Banks observes that while mortality has heavily shaped philosophic treatments of the human condition, the equally bracing reality of birth, or what Hannah Arendt called natality, has been strangely ignored. That particular people give birth to particular people means that history and lived experiences necessarily inform philosophical accounts in her pages, so Banks narrates the lives of people like Mary Wollstonecraft, Sojourner Truth, and Toni Morrison among others in her discusson of birth. It is a refreshing departure from the usual confines that too often write the bodies of these knowers—at least, certain ones—out of the human accounts.

Elshtain saw women as integral not incidental to the maintenance of healthy political community—a vital source of moral friction, even defiance, to its false, totalizing claims.

One of the few scholars I knew of in my early mothering days who put that kind of recognition into academic discourse was the late Jean Bethke Elshtain. It’s regrettable that her name is so often remembered for her moral support of the post-9/11 invasion of Iraq, because what I remember Elshtain for is how seriously she took women’s lives and contributions to the human realm, as well as the significance of human care so often known and performed by women. Tutored by Argentina’s Mothers of the Disappeared, and by the ancient witness of Antigone, Elshtain saw women as integral not incidental to the maintenance of healthy political community—a vital source of moral friction, even defiance, to its false, totalizing claims. It is striking to witness, as I write, Alexei Navalny’s mother, Lyudmila Navalnaya, going to retrieve his body from the Arctic penal colony, and Yulia Navalnaya, Alexei’s wife and mother of their children, who now intelligently mothers the watching world in bravely communicating what is at stake today—tasks that should be inflicted on no one, including mothers.

One of my favourite vignettes in Elshtain’s impressive corpus is her inclusion of notes written by her daughter, Heidi, instructing her in the precise, personal care of her fourteen-month-old granddaughter JoAnn in Who Are We? Critical Reflections and Hopeful Possibilities. Elshtain writes, “Just reading these guidelines exhausted me, and I was reminded: this is what it means to love a child.” The repeated refrain throughout the instructions, “Your day is still going,” is like a liturgical rendering of the deep work that goes into the attentive care of one young life.

But these triumphs aside, most mother tongues advance by way of key phrases that tend to do the thinking for us, not unlike any other realm of knowledge work. “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” “Lean In,” and “I Know How She Does It” come to mind, along with expressions like how nice it is to have someone at home “picking up the slack” or “holding down the fort.” These realms are so noisy with ardent and conflicting prescriptions because the perceived successes and failures are so culturally, economically, and personally consequential. One of the more regrettably mindless ambient phrases—so-called mommy brain—was and remains an expression trotted out for a host of cognitive slips and intellectual spills, all manners of forgetfulness and mental chaos, and an incapacity to engage on a higher plane of conversation. These excuses would reliably and repeatedly sting me with a burrowing shame, but the truth is they stigmatize anyone doing “women’s work.” Writer Caitlin Flanagan’s To Hell with All That: Loving and Loathing Our Inner Housewife helped me see that my bewilderment wasn’t only mine, nor merely private, and that wickedly smart and funny writing helps too—a lot.

So when I recently returned to my old essay, I not only heard but felt the anger, shame, and a genuine battling with ressentiment. Not to be confused with resentment, ressentiment is the suppressed reliving of a negative emotion against someone else. It anticipates injury and revisits old traumas inflicted on previous generations. A politics of shame, for instance, manifests itself as a politics of ressentiment, as Elshtain wrote about with grave warning, fearful as she was for the trajectory of democracies. Ressentiment thrives in realms of neglect, powerlessness, and disappointment, as much in a society as within a soul. Neglected spaces and places understandably fuel anger but suffer from not knowing where to go or what to do with that anger. They are breeding grounds for maladaptive ways of masking and numbing one’s sense of shame. That they are neglected at all means that there were people around who were capable of knowing, learning, and attending who did not.

Contending on paper with the late A.G. was certainly better than other coping mechanisms I could have developed, but there was a reason that, even on paper, I could not simply cogitate my way out of my experience of feeling stuck or helpless. (Indeed, I now see it as a mercy that my younger self never submitted that old essay to any of the publications she once thought would hear her and care. Some of them have since grown quite rancid with ressentiment themselves, and thus more impervious to reality in its human complexity.)

It is an odd thing that I woke up to the pain of my vivisected soul right while I was in the middle of my PhD studies that I began mid-life while middle-mothering. As I studied questions of theological method, from which I once constitutionally recoiled, I also began to know myself better, including my motherly knowing, in all its particularities of embodiment: becoming attuned to signs of fatigue in myself or in my children when we grew surly or sullen, or guarding the precious resource of their attention from the ravages of the digital world. And I now seek to practice these disciplined particularities as unapologetically, intelligently, as I can.

Despite gently if actively scorning the shame in that old essay, something like a nurtured, cleaner anger remains. The anger now is less about me and my own sense of vocational wrestling. It connects, rather, to a deeper lament that confronts ordinary forgetfulness and falsity about what it means to be human with and for others. I still hear my thesis sounding in the depths—mothering is intellectually demanding work—which my younger, labouring self needed to hear stated explicitly.

Concrete Skills of Soulcraft

Matthew Crawford, after having reached the heights of academia and then leaving to work as a mechanic, makes an almost identical argument to my own thesis in Shop Class as Soulcraft. Crawford’s point is that skilled manual labour is intellectually demanding, arguably more so than so-called knowledge work, precisely because it is embodied labour. Abstracted labour, lifted out of the realm of gears, wires, and plugs, often looks down on bodily labour, while at the same time risks growing “de-skilled” in its growing dependency on it. Knowledge work so often depends on labour that it devalues if not holds in contempt. To make every child a knowledge worker, Crawford warned, dooms them not only to a miserably managed childhood, devoid of spontaneity and play, but also to an adulthood of dependency, devoid of meaningful, even satisfying skills, including those that pertain to becoming and remaining free persons. He observes that “any job that can be scaled up, depersonalized, and made to answer to forces remote from the scene of work is vulnerable to degradation,” a degradation that suppresses the human dignity of discernment.

Yet, to my mind, there is something about Crawford’s steely-eyed vision of skilled self-reliance characterized by the manual trades that remains almost predictable, even prudish in the defined boundaries of its knowing. The argument I longed for was one that gave wider recognizable space for the utterly allied knowledge, skills, and capacities related to human interdependency, connection, and kin-keeping as part of the glorious range of embodied human intelligence, work so often performed by women. I didn’t want to merely rebalance some tired equation—“Sure, shop craft, but how about home economics, then, too?”—ensuring that every woodshop class honorific was answered with an Abigail Adams–like entreaty to “remember the ladies!” while distributing dish soap and diapers. I think Crawford is profoundly right to attend from the hammers and nails, gears and valves, in the way that he attends to the larger plane of human work and knowing. He is right inasmuch as dish soap and diapers demonstrate precisely the same intellectually demanding plane of human work as well. Dishes and bodies merit in different ways a similar dignity of care, and both have a way of revealing to us, if we have the mind for it, the range of our capacities to do so.

Dwelling and Indwelling

The lexicon I’m beginning to draw on is Michael Polanyi’s, the philosopher and chemist who began making his way toward a wound in knowing, that sharp rupture between an egoic knower and the world, between the mind and reality that came to characterize modern, scientific knowing. But Polanyi—whose insights were akin but not identical to those of European phenomenologists like Edmund Husserl—refused to be awed by the claims of this separated way of knowing by practicing methodical attention to the world as experienced by knowers.

One of Polanyi’s major contributions to epistemology was his concept of tacit knowledge—that “we know more than we can say.” In Personal Knowledge (1958), Polanyi demonstrates how we come to know, showing not only that detached objectivity is not the essence of knowledge itself but also that the prevailing, almost compulsive commitment to detached objectivity does not square with how humans actually know. Objective detachment in no way securely grounded knowledge; knowledge is always gained by means of embodied persons who are personally vested in questions, processes, and discovery. That Polanyi was not formed in and by the traditional discipline of Anglo-American analytical philosophy, with its particular frameworks, problem sets, and peculiar ruminations, is precisely what made his thinking so fresh. As his student Harry Prosch puts it in Michael Polanyi: A Critical Exploration, “[Polanyi] tended to outflank these problems and to raise somewhat different ones upon grounds on which many contemporary philosophers have difficulty finding their footing.”

Equally captivating is Polanyi’s notion of “indwelling,” related to his exploration of focal perception and the loss of an entity’s meaning. Through indwelling, objects become tools, extending our reach into the world through their skillful use. (Think of using a hammer to strike a nail.) Indwelling “underlies all observations,” Polanyi notes. Anytime we turn our attention in a focal way to something (striking the nail), we lose sight of “subliminal subsidiary particulars” (the hammer). We see through these particulars by indwelling them, not looking at them directly. When we indwell the hammer, and focus the tool on the nail, it is somewhat like the hammer disappears.

Because our dwellings are indwelled, like the hammer, they too tend to recede from view, or, what I feared, they are kept out of focus. And dwellings have been, throughout much of history, the knowledgeable domain of women, but also one to which they have often been restricted, even imprisoned. To have the domus determine the totality of women’s lives is something against which women rightly chafe. But it is also insulting to refuse the domus its due, to devalue and deny its shimmering brilliance, the essential human knowledge housed in our dwellings, by severing its relationship to other human realms. This is a point that Norris stresses: “Our daily tasks, whether we perceive them as drudgery or essential, life-supporting work, do not define who we are as women or as human beings. But they have a considerable spiritual import, and their significance for Christian theology, the way they come together in the fabric of faith, is not often appreciated.”

To have the domus determine the totality of women’s lives is something against which women rightly chafe. But it is also insulting to refuse the domus its due, to devalue and deny its shimmering brilliance, the essential human knowledge housed in our dwellings.

Polanyi recognizes that something of objects’ “original meaning” is lost when we turn to face them focally and particularly, but we also risk gaining deeper understanding when we do. It is risky business to muck around in original meanings—this is, I think, what so many bemoan in the crumbling of traditional ways of knowing, of meanings once assumed to be sturdy, solid, and given. Concrete examples here are essential: When we isolate our attention solely on the brushstrokes of a painting, we begin to taste the loss of the meaning of the painting as a whole. But we can also more deeply appreciate the painting’s particularities, how it contributes uniquely, surprisingly, to a larger realm. Or, another example: As children, my sister and I loved to say a word over and over—I recall doing this with the word “moose” to great effect—until its meaning burst into meaninglessness like an overinflated chewing gum bubble across our minds. Sometimes it would take hours for the meaning of “moose” to reinflate for me after toying with it focally like that.

But it is important to recognize that, once destroyed, meaning can be repaired and reintegrated, never to its “original meaning,” but with the possibility of “establishing a more secure and more accurate meaning of them,” as Polanyi says in The Tacit Dimension, especially “by stating the relation between its particulars.” In some ways, unexplored, creative horizons can present there too. Similarly, in the crush of the duelling idealisms, between the classical pictures of “mother” and “intellectual,” I started pressing on them critically, wondering why some forms of knowing were given such deference and others were denied, and why the relationships between these particulars seemed so separate and distant. Returning to this old essay of mine signalled my commitment to draw these parts of me and my vocational labours into a more peaceable, liveable wholeness.

Attending to the relations between particulars necessitates a willingness to “look around thoroughly in this round-about-us,” a quote I lift from philosopher Mary Townsend’s reading of Heidegger in her subtle 2016 Hedgehog Review essay, “Housework.” In it, she grapples with housekeeping, the phenomenological philosopher Martin Heidegger (a student of Husserl), and with what it means to know our dwellings as our indwellings.

The great Covid pandemic forced some looking round-about-us, bringing to the fore the people, places, and meanings of work and home, and the relationships of life’s particularities. Of course, lockdowns landed inequitably among members of a household, even as it did within and among nations, demanding ever more from some, and accommodating ever more for others. In that strange, sifting season, there was risk and real opportunity for many to recalibrate, a window to focally attend to that which we so often attend from. What are we already forgetting? How can we secure a deeper understanding now that the original “meaning is effaced,” now that some feel the shaking coming to an end?

Charwomen and the Philosophers

Despite their low standing, the charwomen do not fail to stand out. Whether in Sertillanges’s periodic references to them in The Intellectual Life or in other writings on the life of the mind, these domestic cleaners hover around the philosophic periphery. Townsend notices them too, and doesn’t hesitate to speak up for them; but she also turns her mind to them and the realm they represent. Townsend asks, “Why should the work that forces us to reckon with things we usually ignore be mindless? Why would the most concrete work be the most absentminded?” To my mind, Townsend is right to press hard on the very ground of our dwelling and indwelling as the material stuff of philosophy, while refusing to sentimentalize the actual work that still needs doing, refusing to devalue those who do it.

Why is it bestselling brilliance for psychologist Jordan Peterson to say “make your bed,” but not when your mother teaches you to do it?

The same could be said for basic skills in caring for one’s home and for the people who dwell in it by means of caring for the things within it, a subject Cheryl Mendelsen maps in her magnificent 1999 Home Comforts reference manual, in which she laments housekeeping as a dying art and an orderly science. While they may never properly iron linen table napkins, children and adults alike gain much from cultivating the skills required to bring livable order to ordinary chaos. It is a balm to have that skill in one’s pocket, not because it exercises proto-dominance on an indifferent universe, but because it can also bring clarity and calm to one’s cluttered interior. It mirrors exactly what thinking effects. Yet why is it bestselling brilliance for psychologist Jordan Peterson to say “make your bed,” but not when your mother teaches you to do it?

It is often the work of women to pass along this kind of embodied brilliance, and the suffering of women that it is so often taken over and put into a male’s mouth. At archaeologist Jennie Ebeling’s 2012 lecture at the American Center of Research in Amman, Jordan, I remember the sting of grief and anger as I listened to her discuss the practices of Near Eastern breadmaking, how women so often milled the grain by hand, whose fingers made the daily bread. As industrialization made its way into breadmaking, these skills evaporated. The machines did the work, and the women were alleviated from their knowing. There’s nothing to wax nostalgic about here; these original meanings have exploded. To insist on their return is no sure path of liberation. I would not like to spend entire days milling grain, nor would I want to have that be my daughters’ determined destinies. But I will admit to feeling stings of frustration when I’ve seen Netflix documentaries of high-end chefs in world-class restaurants filmed walking backlit in the gentle breezes of their fresh herb garden, or while foraging for mushrooms, or demonstrating a lost technique for preserving food in jars, while diners book tables years in advance as if they were starving. Again, why is this considered “knowing intelligence” in a celebrity chef’s hands but not in the hands of their great-great grandmothers who did it long ago?

Years ago, I attended the funeral of the grandmother of one of my childhood friends, a woman who had taken me into her heart, even though we were not kin. At Edith’s funeral, I was struck by the many people who eulogized her, remembering with good humour her sublime pleasure and competitive skill in getting the Monday washing done and out on the lines before any other housewife did. Those great sails, flapping in the bright breeze of my imagination, fill me with respect for her intelligent, skillful self-reliance, sure, and also for the fact that she knew how to tend to a younger someone like me.

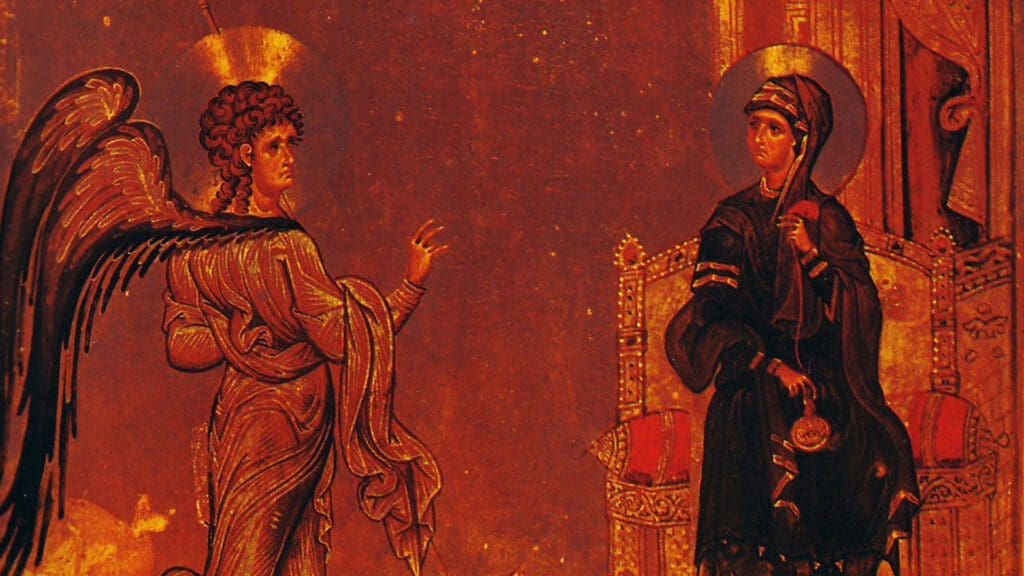

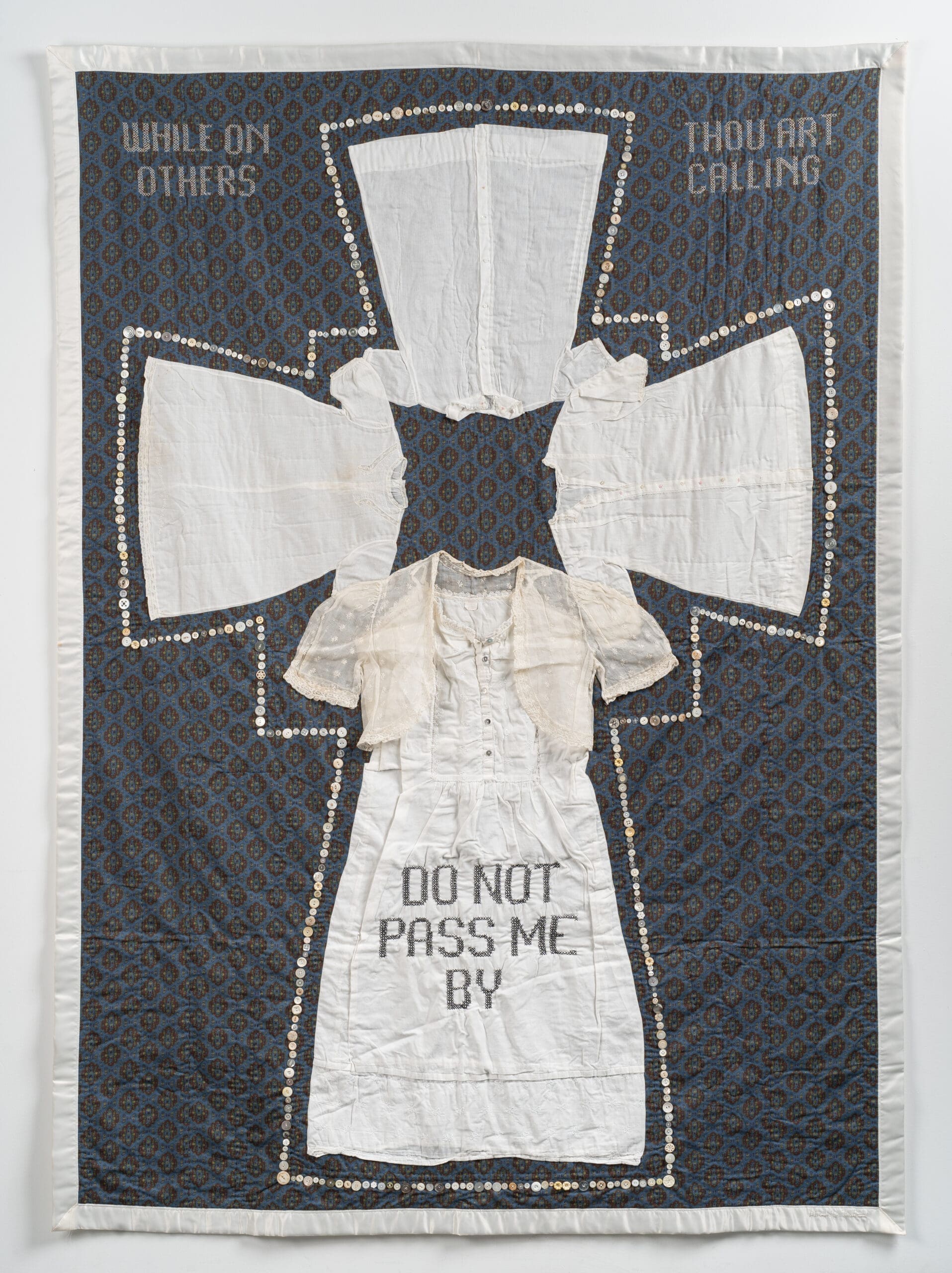

I cherish the original meaning in the memory of Edith’s lines of laundry, but I am equally glad for new meanings unearthed by artist and mother Michelle Berg Radford, who paints images on the kinds of textiles Edith may have once hung, on another kind of artful laundry that now hangs in art galleries and private collections, testifying to a deepening understanding of her own and others’ mothering labour in her artwork. I look too at the life and work of artist and mother Cayce Zavaglia, whose artful embrace of her own mothering realities necessitated that she relinquish the toxic paints and chemicals of her earlier art-making and take up “painting” her astonishing portraits with embroidery needles and thread instead. These are calls and responses, neither mutually exclusive nor necessarily suspicious. In the same spirit I give thanks for mothers who are also architects and designers of built spaces, who parent children with disabilities, like mother-architect Jessica Moxham, author of The Cracks that Let the Light In, or mother-designer Sara Hendren, author of What Can a Body Do? How We Meet the Built World. Their mothering experiences strengthened their intellectual discoveries about the world and did not diminish their skills in design, equipping them to “outflank” and creatively counter a world not designed for their children nor for many others. I could name many more, including those with no biological children of their own, but who reach out into the world with their own bright, generative brilliance, who offer their needed personal knowing to the world, listeningly attentively to it and the particular people given to them.

The younger mother in me needed to learn how to turn toward and endure the pain of these wounds of knowledge, to refuse pretending that the ideals were merely liveable, and to learn to refuse ressentiment—particularly because my mind was labouring in intelligent service to others’ minds. In other words, I was learning how to know, care for, and love particular people in a particular time. The pleasures and intelligent demands of any form of human care are available to any human being hopeful and brave enough to learn and fail and try again on behalf of vulnerable others, which means all of us. This deep work of caring for particular people is tacitly and explicitly ours—mothers, fathers, uncles and aunties, godparents, grandparents, and neighbours, in the time given to us, for and with the people given to us, within the actual givens of our lives.