On a lonely stretch of Livonia Avenue at about midnight, I was surrounded by a group of thick-necked toughs. I remember how thick their necks were because they wore flashy gold necklaces and had big bracelets on their arms. The biggest came right up to me and with a steely look asked, “What are you doing here?”

A Journey through NYC religions is searching for every sign of religious life on the 6,374.9 miles of streets, uncounted alleyways, and shopping malls of New York City, seeing the city as a microcosm of the dynamic, pluralistic society we find ourselves in. It is the preeminent global city and the largest in the United States. It produces far more gross domestic product than any other region of the country. Do the trends in New York City portend increased secularization around the world? Or is it a leading indicator for a reversal of secular trends and a resurgence of religious faith? Are we beginning to see the rise of post-secular cities— not quite religious capitals, but not secular either?

Since 2010, we have visited over eight thousand religious sites, taken tens of thousands of photos and videos, interviewed thousands of people, and published over eight hundred features on our online web magazine. Tonight, it was my turn to do the reporting. I had bumbled into a trap.

I had my big Nikon out to take photos of the beautiful murals on a block of Livonia Avenue. Often, the time to meet church people in mean neighbourhoods is at night when they provide safe study and play spaces for their kids. However, everyone had already left the church and school of New Grace Christian Center. I hadn’t noticed these residents of the streets, which were darkly shadowed by the elevated subway tracks. Livonia Avenue of East New York and Brownsville, Brooklyn, was the worst dark remnant of the sinister New York of the 1970s.

In my situation, I faced my skeptics, who seemed prepared to give me a thumb’s down on my reasons for being in the neighbourhood. My smarts were coming up with few options. If there was no God or no church, I would have had no allies that night.

I looked around and pointed to the murals. “I am shooting those,” I said. (Not exactly the right turn of phrase.) “They are so beautiful and moving. People ought to know about them.”

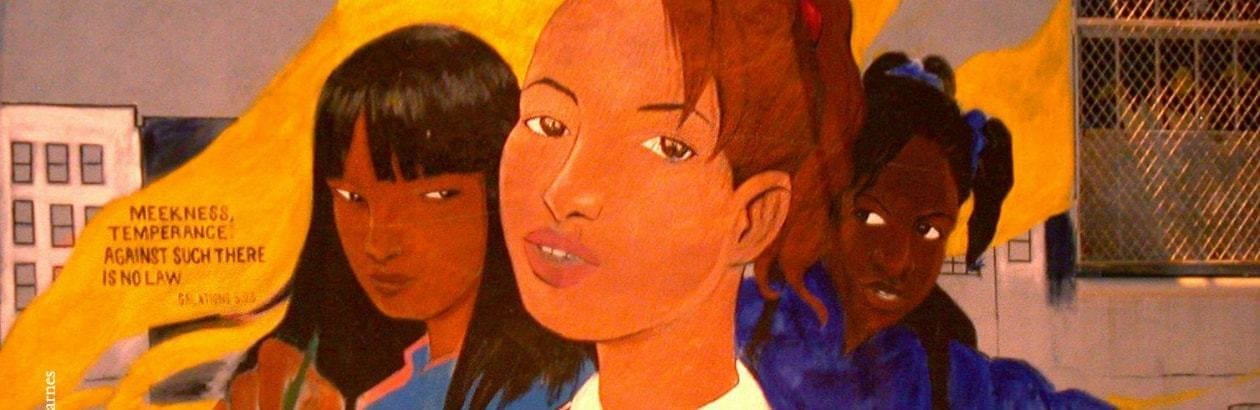

Indeed, the murals were magnificent, two-story-high portraits of kids applying the Bible to their lives. They were kids who showed hope and determination in their faces. The murals spread down almost half a block and around the corner. One young girl, eyes closed as if praying, crosses her arms in an X over her chest. Her school uniform also forms a cross on her chest in between her crossed arms.

Tree leaves hang over her head. They are not all green—there is a brown one hanging down too. Life is not perfect on Livonia Avenue even in this haven of learning and peace.

Still, swirling golden rivulets cross in front of the apartment buildings and centre on her. In one swirl, we read the apostle Paul’s admonition, “Put on the whole armor of God, that ye may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil.”

Her stance, however, is not militant, but one of serene innocence. Her inspiring face rises through and over the rough plaster walls. She seems to model Mary, the mother of Jesus.

In another part of the mural, a young boy also wears a white shirt with a tie, and his book bag is slung over his shoulder as if he were going to the office. He looks back on a biblical proverb that flows in a golden river downward over a factory-looking building. It says, “Train up a child in the way he should go: and when he is old he will not depart from it.”

The artist has managed to portray the student in the present reality of Livonia Avenue as he looks toward his future success. There is a double-consciousness at work here: while he looks to the future, his eyes also gaze directly on the value taught to him from the school that will bring him to his goals. This diagonal in the mural takes you backward and forward in time, pushing your consciousness of time and eternity into a continuous dialogue. One thing this pivotal moment tells us: the African American students on Livonia Avenue are not a problem; they are a resource for our city’s future. They push us past the veil of racism in Babylon to drink new sweet waters.

It was uncanny that the murals were unmarked by the graffiti that covered every inch of the other walls, the overhead subway pillars, and the garbage cans.

“Do you know who painted these murals?” I asked.

The leader looked at me with slight disbelief. “No, I don’t know who did those.” He just stood there looking at the murals and me. I wondered why he was pausing.

“Do you know who the pastor is of this church?” I continued, pointing to the name New Grace Christian Center.

“No, man, I don’t know that!”

I wondered if I was losing my audience and if our encounter was about to go in a more dangerous direction. “What is this church like?” I asked, as if he were giving out Sunday worship tips. “Is it any good?”

To you, this question must sound like a thin, slightly stupid inquiry. I sort of thought that too, but I was more enraptured with the human loveliness of the murals. I was excited by the character of the kids in these drawings. Despite the danger, I just couldn’t help but wonder what the present audience thought.

The boss man’s two aides-de-camp moved closer. He looked at me in a moment of hesitation, apparently wondering whether I was real. Then looking at the murals, he edged toward my emotion. It was a moment of communion. I believe we both felt it.

He explained, “Mister, any church in this area is good.” And with that he and his posse walked away into darkness.

The mere fact of the church and the exhibition of its character saved me a lot of trouble that night. The boss man and I stood in God’s presence, the Host was risen in the murals, and there was a moment of shared reverence.

The moment was brief but fateful. The minute details of faith on the streets of New York City made a difference that night. What if the church wasn’t there? What if the murals were not gospel-centred beauty? Would the evening have turned out differently?

I had only God’s grace. I had fumbled away any advantage that I might have had when I got out of the car.

Later, the question occurred to me that maybe these guys thought I was a threat to these murals, that I was going to mark them up with my own tags. I was the foolish troublemaker in their estimation. My recognition and reverence toward the neighbourhood’s spiritual beauty had partially validated my presence, just enough, in the boss man’s eyes.

That street tough was touched by God too. His humanity was not swallowed forever by the street life. There was a light on the door for him. Maybe he came up to me because he thought I was threatening to deface this rare treasure on the street. The kids portrayed on the wall—so, so obviously— represented the hope for a better life. He perhaps felt that I did not have respect for the truly good things in this poor neighbourhood. Maybe he was going to make me pay until he saw my spirit for the murals was his too. There was light on the door for me too.

We were briefly almost brothers in Christ. A fleeting moment of grace undid evil for a moment. Could we have more than a moment of grace?

Those murals are still there on Livonia Avenue, still proclaiming that a spiritual city is the ideal city. A churchless city? My answer is personal—over my dead body. Secularism would have been a real killer that night on the street.

Grace That Zigzags

The modern city tells a more complex tale than one of inevitable secularization. So are the testimonies of spiritual conversion more than simple unidirectional tales.

Very often, the salvation stories are sudden U-turns, or God is intertwined into a life that zigzags between gods, failures, and unfinished tales. The narrative may be static and then catastrophic and then put back together again. The Livonia Avenue murals are an example of such spiritual complexity. We might call this story the post-secular narrative of the city: off any preset grid, ambiguous sometimes, in between failure and triumph. Truth, hope, and salvation tangle with a lack of inevitability, no necessity, no stages of life continuous toward a certain end. The modern city is much like the triumphs, failures, and wanderings of the Israelites in the desert. God is there, God speaks, God acts—but what a crowd of contradictions burden his followers.

The painter of the murals grew up in one such off-the-grid family. Wong Dowling was born in Bamberg, South Carolina, in 1978. The life of his mother, Geraldine Moody Dowling, took quite a few tumbles. Yet she kept on a winding path toward Jesus. Our reporter Pauline Dolle has tracked down the story.

After Geraldine’s mother died, her father remarried a woman who was “not fond” of Geraldine, she recalls. The household became tumultuous. With a fiery spirit, she ran away to New York City when she was ten, though she looked older. She eventually returned to South Carolina, where at age fifteen she married a charming army officer named Gary Dowling. Then she discovered that he had a dark hidden side left by the scarring of warfare. He was an over-controlling manic depressive who would hit out if contradicted.

He kept Wong and his other four children on a strict regimen, ringing a bell to have them line up for dinner. An added burden was that one son, Meko, was hit by a car and paralyzed. The stress on the family was increasing exponentially.

The husband would drill Geraldine like a sergeant, making her march back and forth, polish his shoes, and so forth. Angry at the rough treatment, Geraldine packed her husband off to his family near Boston, Massachusetts. But she soon made another mistake with men, though it opened some doors for her son.

In 1985 she met another romantic man, this time one who was half Spanish and half Caucasian. Because the South was unkind to such mixed relationships, they took off to New York City. There, Geraldine worked at an art supply store. The artistic bent seemed to appeal to her son also.

Wong rode in the backseat of this interstate family drama with a coloured pencil clutched tight in his hand. From the age of two, Geraldine recalls, Wong always wanted to draw. When his two new younger sisters, Victoria and Sparkle Corujo, went to church with their elementary school teacher, Wong stayed at home to draw. He also started to demonstrate his strong will to do things independently and privately.

Geraldine bought Wong a desk for his drawing, but he spurned the use of it, instead sitting on the floor. He would draw every moment he could, compulsively putting in the ten thousand hours to perfect his artistry well before he became a teenager.

At elementary school on Vermont Avenue, Wong spent more time doodling in class than maybe listening. At least, his childhood friend Derrick D. Turner remembers that Wong would fill every margin on his worksheets and writing paper with cartoons. His specialty was drawing superheroes, which he would sell to his classmates for twenty-five cents.

“Art was his . . . talent God gave him to share his perspective with the world,” Turner marvelled. He recalls Wong as reserved until you got to know him. Behind his quiet facade, he was reimagining his fellow students as various types of superheroes.

Wong identified with the Bronx-born rapper Kool Keith, who channelled a pantheon of alter egos through his lyrics. The schizophrenic creativity that could form whole personalities for his hip-hop appealed to Wong’s own eccentric, private path. He took on a hip-hop alter ego called Wongy-D.

The alternate world provided, perhaps, some relief from a deteriorating home life. His mom’s fiancé had turned to drugs. Disbelieving his promises of rehab, she left and moved into the East New York projects when Wong was fifteen.

Fortunately, her son was able to attend Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music and Art and Performing Arts. He breezed through, picking up an interest in Japanese and Swahili. He was still pretty reserved and worked on his art without much conversation. Somehow, he learned how to paint murals freehand, a near impossible task.

One day, muralist Janet Braun-Reintz told her flatmate that she had found an unusual kid in East New York. “Shelly, I found a kid who can paint off the grid.” It was Wong Dowling.

Most muralists use a scaling grid to transfer their drawings onto large-scale walls. The sketch is used to map out each point on the wall according to the proper proportions. Even veteran muralists carefully follow the grid. Wong could go directly to the wall and do freehand drawings with the right proportion. The two artists started using Wong to work on their murals in East New York.

In 1994, Dowling painted his first solo wall, a petition for the city to put a stoplight where many pedestrians had been hit. He also started doing comic drawings.

In 2001, Stephanie Smith of New Grace Christian Center School saw some of the murals and asked Braun-Reintz if someone could do murals for the school. Wong showed up “with no fanfare” and got to work. His drawings were very in tune with the kids in school, the role of faith in guiding them to success, and the dangers that they faced. Although Wong was not very involved with his family’s Christian faith, he found some stability in teaching art at the Christian school. However, he kept his private life separate.

Meanwhile, Dowling, Turner, and another friend, Chaz Staton, launched a project that told the story of hip-hop’s revitalization by a descendant of an African tribe. One thing Dowling insisted on was that they would not sell out to big corporate sponsors but publish on their own. They started printing the “Chronicles of Hip Hop” in small batches. Turner noticed that whenever conversations turned toward personal matters, Dowling fell silent. The young artist was using the money he was earning from the school to launch himself into the homoerotic East Village. Eventually, he caught HIV/AIDS.

Wong refused all treatment. Flipping off Turner one day, he shut the door on any further conversation and walked stubbornly toward his death. Even as he lay dying in his mother’s home, he told friends that he was working on his art. All he wanted to do, Geraldine recalled, was to draw. In his final work, commissioned by the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, he drew portraits of the pastor Martin Luther King Jr., the runner Jessie Owens, and ninety-eight other African American luminaries.

One day, lying in his mother’s arms and surrounded by his art, Wong told her, “I have to go.” Smiling to his family, he closed his eyes for the last time on January 11, 2007. He was buried at Thankful Baptist Church in Bamberg, South Carolina.

As a legacy to her son, Geraldine is now studying theology to become a pastor and plans on opening a church in Brooklyn to reach out to all the broken families and their youth that she has known so well. One of Wong’s most moving pieces still watches over the neighbourhood that raised him. The eyes of childhood, maybe his childhood too, look out, warily and hopefully, from the walls of New Grace Christian Center School.

Can we imagine the city without faith that travels like spring water into all sorts of lives? There are a variety of pains and hopes in the city: Jesus kneels to the wounded and raises up hopes in the most unlikely places like Livonia Avenue, the Dowling family, and Tony Carnes.

The New Livonia Avenue

The murals and their muralist are still grabbing the attention of passersby. Sometime after I first saw the murals, I and another reporter for A Journey through NYC religions visited Graffiti Church in the East Village of Manhattan. The church is led by Pastor Taylor Field, who is well-known in Southern Baptist circles for his books such as A Church Called Graffiti and Upside Down Leadership on ministry in the roughest, poorest areas of the city. As we talked about our travels down every street and alleyway in the city, he asked us where the worst part of the city was.At that time, the depressing truth was that Livonia Avenue was a bad place, maybe the worst in the city. That’s what we told him.

Social scientists like Robert Sampson at Harvard University have found that bad areas tend to pass on their badness through the generations. Some policy-makers wonder if the only solution is for people to move out to better places. Or promote unbridled gentrification. Our experience on Livonia Avenue is that this reading of the poor urban areas may be a little too hasty and simplistic. It overlooks the sedimentation of religious meaning that courses through the veins of a neighbourhood like an essential vitamin. How had the residents persevered against all odds? From where did this strength and moral commitment come? Who or what held things together before the gentrifiers came along?

The Christian school on Livonia Avenue reached out to muralist Wong Dowling. It gave him the opportunity to reflect in his own artistic way about the impact of biblical faith on kids. He himself wasn’t able to make it out of trouble. But many kids at the school have. His mother is dedicating her life to ministry to reach out to the kids who remain. It is a stereotype to see the slum as a monolithic area of depression and despair. Most people in the area go to jobs, raise families, and promote their kids toward a step up. They are also there to help those who are not making it.

With local intelligence, church networks direct flows of resources. A year or two after our visit to Graffiti Church, we heard that the pastor had sent forth his son Owen Field to found a legal and community centre near Livonia Avenue. Owen found it tough going at first. First, he found some local ministries and churches that were willing to help him to get to know the area. Working with them for a year, he learned some realistic lessons.

His initial emphasis on a legal aid centre was most appreciated by its clients and built up some trust. The Graffiti group also started to reach out to young adults. However, neither effort was leading very fast to a larger, more significant impact. For various reasons, the older folk and the younger adults couldn’t make long-term commitments. The adults were weighed down by family and job responsibilities. Too many of the teens and twenty-year-olds had already fallen into irregular habits associated with street life. So, the ministry zigzagged one more time toward reaching kids first as a way of building stable, long-term relationships. A local church offered its facilities.

Ministries like Graffiti 3, New Grace Christian Center School, and churches in the Livonia area continue like hearts pumping out life to those on the precipice of death. They have dealt with some of the most convoluted personal situations. Many of their clients, students, and members thought they were headed into the old straight-as-an-arrow-to-jail-and-hell story, then their life zigzagged in a different direction. Locals sometimes cannot believe how some people’s stories radically veer in a more hopeful direction.

That night when I first encountered Livonia Avenue I also met an immigrant from Colombia and his son. They were locking up the church van after taking people home from church. It was a little before midnight. He shared his story with me.

His struggle in the city as a new immigrant was very hard. He started drinking heavily to kill the pain and to get up in the morning. Addicted, he lost his family and son. Then, one day, he heard the music coming out of an African church. He felt a power drawing him into it, sat at the back, and listened to the sermon. He felt a Power come over him. He recognized that it was the presence of Jesus Christ. His life then veered away from the precipice of destruction. Now, he is a deacon at the church, his family is back together, and he provided me with some testimony, prayer, and comfort on the street that night. The artery running spiritual power to me came from Africa through a Colombian to the Brooklyn streets.

I left and went over to Livonia Avenue reflecting on how much I was learning about the unexpected presence of God’s grace in the loneliest area at the loneliest time of the night. I went down the street with new eyes and arrived at the murals. And I saw the illustrated words of God come pouring off the wall of the church school to free me from seeming disaster in a street trap that had locked its jaws on me.

One Livonia Avenue native told me later, “The Word is the key that unlocked some handcuffs here.” Inevitable stories disrupted in the post-secular city.