L

—Sergius Bulgakov, Unfading Light

Creation and the fall are conceptually distinct but factually simultaneous.

—Hans Urs von Balthasar, Cosmic Liturgy

My salvation is bound up with that not only of other men but also of animals, plants, minerals, of every blade of grass—all must be transfigured and brought into the Kingdom of God.

—Nikolai Berdyaev, The Destiny of Man

God’s Ubiquity

“Late have a loved you, beauty ever ancient and ever new,” said the African doctor of souls. But Augustine did not know how late. Late as in billions of years after whatever it is we call the universe began. I too will address you, Lord, as he did, though so much later than he did. Later in cosmological time than Augustine knew, later in life than he wrote, for I am older than he was when, in his early forties, he penned his Confessions. And later, of course, in human history than when Augustine addressed you, even if that minor interval of sixteen hundred years evaporates in the face of your timeless—no, make that timeful—beauty.

Rock with ancient coral and other marine life found on the shores of Georgian Bay. Photo by John Hawkins.

I hold your beauty in my hand, O Lord. I do not mean that I presently hold the sacrament of your body, although I did do that last Sunday, briefly before I consumed it; and I expect to do the same in the Sabbath to come. It would be too easy, however, to discourse on your presence in that transfigured bread. Instead, I hold in my hand a rock with pieces of fossilized coral embedded within it, remnants of a tropical sea that blanketed the land I live on hundreds of millions of years ago. It was found innocently enough on the beach of Georgian Bay by my enterprising nephew Micah. I wish to ask you about this coral, Lord. G.K. Chesterton said that the poets have been strangely silent on the subject of cheese; and your theologians, it seems to me, have been strangely silent on the subject of coral.

Ensconced in this ancient stone, alongside the coral, are remains of a few slugs and snails, known as gastropods. Beside the gastropods are some Bryozoa—that is, moss animal invertebrates that lived in colonies. These were, it seems, food for the gastropods. Alive as these animals once were, their habitat was also alive. This branch of coral from the Ordovician age, in fact, is itself made up of skeletonized colonies of once–living creatures. Coral, as I see it, is an uncategorizable thing: it is tree, animal, and mineral at once. But can we add one more category to this already impressive list? “He is sun, stars, fire, water, wind, dew, cloud, cornerstone, and rock,” said your servant St. Dionysius the Areopagite. “He is all things and not one being among other beings.” Do I therefore hold not merely your beauty in my hand, good Lord, but you? After all, as St. Paul insisted, “the Rock was Christ” (1 Corinthians 10:4).

Coral, as I see it, is an uncategorizable thing: it is tree, animal, and mineral at once.

I do not think St. Augustine would agree. He asked you about coral long before I did. Or, rather, he asked the coral itself about you: “I asked the sea and the deeps and the creeping things, and they replied, ‘We are not your God; seek above us.’” So I do not think this rock is you. Nor really, if one keeps reading the text I cited, does St. Dionysius. “You are drawn from the transcendent throne above all things to dwell within the heart of all things, through an ecstatic power that is above being and whereby he yet stays within himself.” So, however much you might be mysteriously present in things, those things are not entirely you.

And for this I am glad, for if you are this rock, if you are the now-dead creatures embedded within it, Lord, I am not sure I entirely like you. For what I see is death. Indeed, when, as a Platonist, Augustine imagined your presence penetrating all creation as the sea pervades a sponge (which is as ancient as coral), he too was dissatisfied. After unfurling his grand marine analogy for how you pervade the universe, Augustine immediately then had to ask, “Where then is evil? What is its origin? How did it steal into the world?”

And not only Augustine. Charles Darwin’s first monograph was on coral reefs and was printed in 1842, well before The Origin of Species in 1859. In that early work Darwin tells me something about the formation of coral, but his more troubling questions (and potential answers) would come later. And I have those troubling questions as well, Lord. In that famous letter to the American biologist Asa Gray, commenting on the way a parasitic wasp feeds off the flesh of unwilling caterpillars, Darwin wrote this: “I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of Caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice.”

I would only add, Lord, that the question can be posed about the fossilized rock I hold in my hand as well. The gastropods that feed on the Bryozoa which became an ancient reef, now long dead, illustrate the same dynamic that troubled Darwin, only on a less dramatic scale. Darwin wrote in the same letter, “I had no intention to write atheistically. . . . I feel most deeply that the whole subject is too profound for the human intellect. A dog might as well speculate on the mind of Newton.” But, dog though I may be in comparison to you, Lord, I am not so hesitant. I will not thwart my questions with timid reverence. I feel pressed to speculate—or, better, to ask you directly. Endless eons of death untold mean the rock I hold is but one of a trillion tragic tombstones. Attractive as the God-drenched mysticism of St. Dionysius may be, if I do hold “you” in my hand, I am horrified. If it is true, that you are “the All” (Sirach 43:27), the All has some explaining to do.

A Cross in All Creation

Perplexed by all of this, I turn to another of your ancient saints, Irenaeus. I wonder if it is he who unravels the mystery of coral more than Augustine or Dionysius, and certainly more than Darwin. In Proof of the Apostolic Preaching, Irenaeus said this:

In these words, Lord, the mystery of this rock more fully unfolds. I understand that you pervade the whole world, myself and the rock I am holding as well. But Irenaeus also gives me a way to make sense of the death I see within it. He even says you were “crucified in these,” which cannot but include the Bryozoa and the gastropods. What I hold is therefore even an imprint of the cross, on which you—hundreds of millions of years later—would die. Because you are the “lamb slain from the foundation of the world” (Revelation 13:8).

When the gentle caterpillar sustained that parasitic wasp, was that a dim reflection of you who became the bread of life, fit to be consumed? When the Bryozoa gave its life for the gastropod, both of whom would become particles of the reef whose fragment I hold in my hand, was that also a distant intimation of Calvary’s hill? Did not Czesław Miłosz answer Darwin’s query about the cat and mouse when he wrote that if you “take pity / On every mauled mouse, every wounded bird. / Then the universe for [you] is like a Crucifixion”? When St. Ignatius, on the way to his martyrdom, wrote to his congregation, “I am the wheat of God, and am ground by the teeth of the wild beasts, that I may be found the pure bread of God,” had he conformed to the grain of the universe at last? Most certainly yes. But this cannot be the way you first made the world.

Here I turn to modern theologians. David Bentley Hart puts it this way:

I think this is right, Lord, as I have discussed with your servants before. The event of the fall, and the very real introduction of death that came with it, is beyond time as we know it now. In the words of Sergius Bulgakov, the fall is “connected with our history . . . [and] inwardly permeates it.” Surely it inwardly permeates this rock I hold as well, Lord, as do you. Another theologian, Alexander Khramov, helps me here. He shows me why I have never been satisfied with those who, seeking to reconcile the Christian faith with evolution, have made their peace with death. He shows me how many of your ancient saints thought as Irenaeus did; he helps me see how only after that mysterious catastrophe did you make this world “perishable to fit it with the corrupted state of humans.” What I am wondering, along with the young theologian Jesse Hake, is whether the fall into death took place before the big bang, and whether you, in your mercy—as Brother Lawrence once put it—fell with us. Olivier Clément puts it this way:

I can turn to literature to see this as well, Lord. In J.R.R. Tolkien’s Silmarillion, this world of death is one that you allowed, but only after an entirely good creation (the first theme), and only after evil (the second theme) intervened.

I see those three themes in this rock, Lord, all three “musics.” I see the goodness of your creation shining through it. I see those once magnificent stretches of pristine coral that wreathed this part of the earth in a beauty yet unwitnessed by human eyes. But I also see the second theme, “aeons of myopic striving . . . [an] orientation away from God, and in the direction of ruthless self-assertion.” Even more, I see the third theme, that late and solemn pattern, the theme of your gospel. I see the prospect of the world of death overcome, the world in which you would ultimately intervene. You are not, then, the rock, my Lord. But perhaps you are the Bryozoa within the rock that gave its life for the gastropod, and which then composed this petrified reef. Is what I hold in my hand then a prophecy? This sacrificial impulse may be what Sarah Coakley, working with biologist Martin Nowak, called the “thin purple line” of evolution that moves from mere selfishness to cooperation and sacrifice.

This sacrificial impulse may be what Sarah Coakley, working with biologist Martin Nowak, called the “thin purple line” of evolution.

Robert Farrar Capon says that your grace is “a gift hidden in every particle of creation, a gift that goes by the name of the mystery of Christ.” Sarah Jane Boss insists that “human destiny is bound up with the rest of creation.” And in his astonishing book The Difference Nothing Makes, Brian Robinette refers to God’s “deep incarnation” and “deep resurrection” within matter itself. He cites Elizabeth Johnson’s claim that “Christ is the firstborn of all the dead of Darwin’s tree of life.” You, Lord, took cosmic suffering into your life without allowing that suffering to jeopardize your aseity. “The death of Christ,” writes Niels Gregersen, “becomes an icon of God’s redeeming co-suffering with all sentient life as well as with the victims of social competition.” You, the giver of life, says Johnson, are “silently present with all creatures in their pain and dying,” even the creatures fossilized in this rock. As Robinette puts it, this is Easter’s true “cosmicity.”

Cosmic Art History

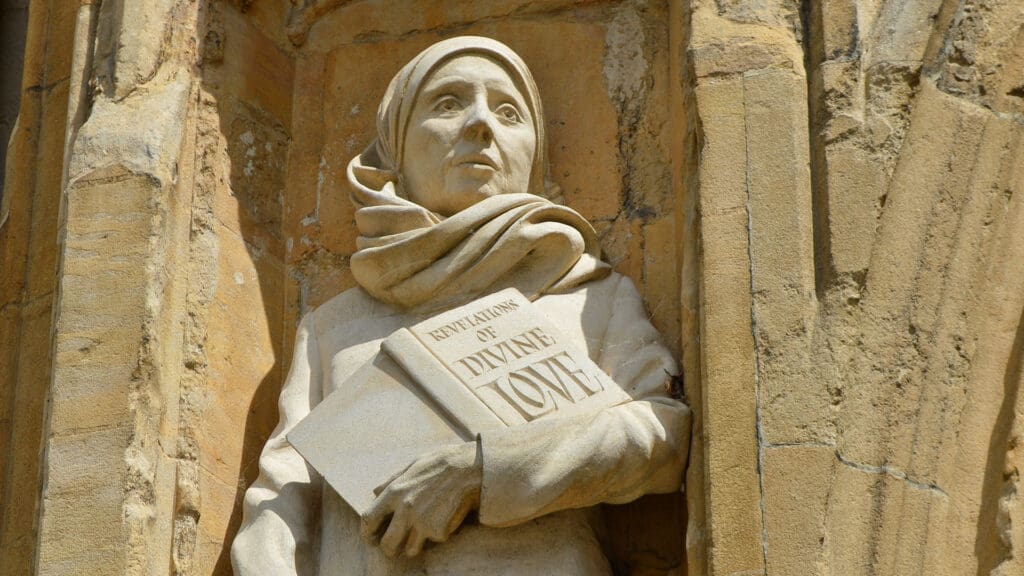

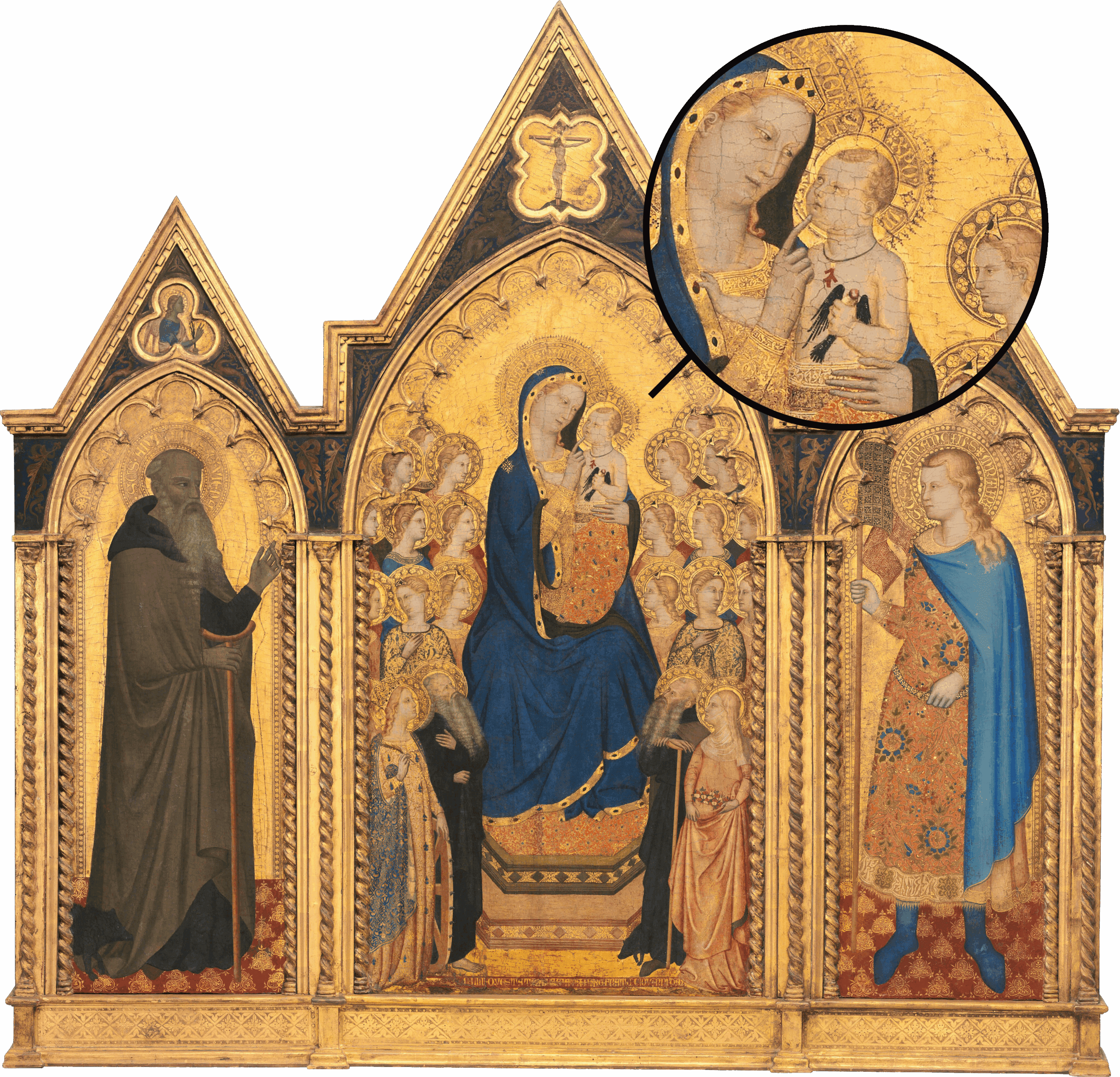

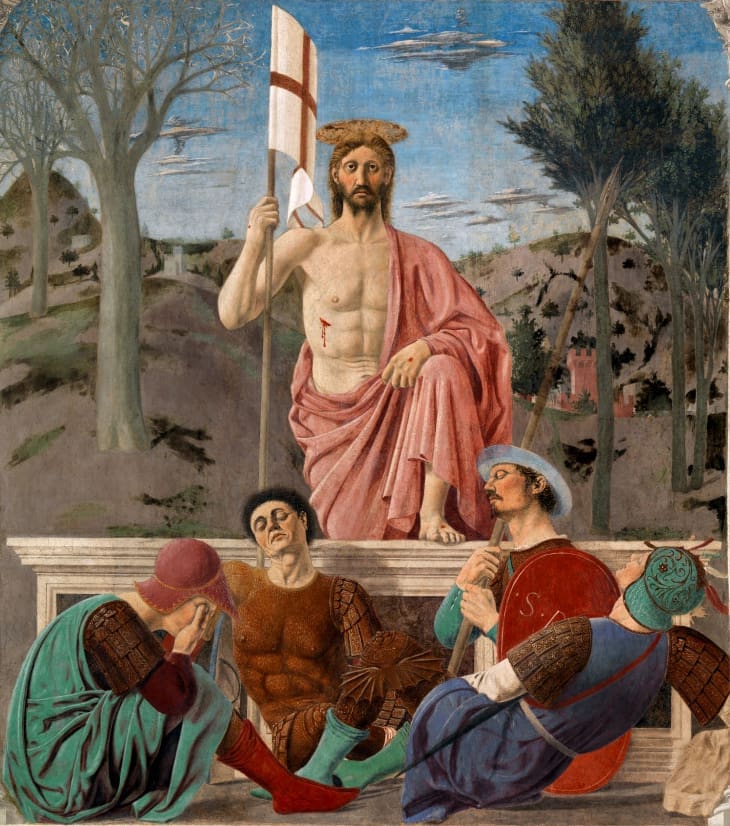

I turn not just to theology, not just to literature or music, but to art as well, Lord. Now I understand why you are so often depicted with coral, even with coral in the shape of a cross. Not only did the great Piero della Francesca do this in the fifteenth century. Your servants Masaccio, Schiavone, and Puccio di Simone and Allegretto Nuzi did the same. They, and the theologians and scholars who advised them, also saw you in the coral. Their “science”—perhaps best to call it natural philosophy, so well mixed with theology—was in some ways more advanced than the science of my own day. Because of their belief that coral petrified on contact with air, they said coral intimated the resurrection, owing to its “wonderous resistance to biological decay.” Piero painted your victory over death as well. “The greatest painting in all the world,” in Aldous Huxley’s words. Now it seems to me that the dribble of blood emanating from your wound in that painting resembles the coral I now hold in my hand.

Aided by your saints, assisted by bards and painters, I am coming closer now, Lord, to the mystery of this rock. You have an intimacy with things that I cannot fathom, almost so that we can say that you are those things. I even once saw an image of you not decorated with coral but as coral. There are more than a few instances, here and there, where you don’t wear coral but you are it. Indeed, how could there be such a thing as coral, how could there be anything, without you? But I cannot stop there, Lord. For you are not death. You are not sin or evil.

This rock, and the struggle embedded on it, tells me that you allowed this world of death, but only because you planned to rescue us from it. I hold a blueprint of this plan in my hand. This plan, according to your servant St. Maximus, “was known to the Father by his approval, to the Son by his carrying it out, and to the Holy Spirit by his cooperation in it.” Maximus continues, “The aim was, that by experiencing pain we might learn that we have fallen in love with what is not real, and so be taught to redirect our power to what really exists.” And what really exists, Lord, is not this rock, not this coral, not me. What really exists, O Lord, is you alone.

If the late Darwin said “science has nothing to do with Christ,” it was because he was too unfamiliar with Augustine, Dionysius, Irenaeus, and Maximus, who have helped me.

If science has nothing to do with you, I answer that it is then barely even science, if by science we mean that which is worthy to know. I even know of one church, Lord, built in Darwin’s lifetime, where the fossils that he wondered about, and which I hold in my hand, are built into the baptismal font. At All Saints, Margaret Street, in London, there is the coral, which joins with the choral praise that sings so sweetly of your beauty, so anciently new.

Thanks to another of your servants, Fergus Butler-Gallie, I even know of an entire church constructed from coral. It was built on the largest slave market the world had yet known. By the 1850s, thirty thousand souls were sold at this market each year. Up to two hundred thousand were enslaved on the island at this monstrous market’s peak. And while Islam allowed more leeway to permit the trade, by 1873 the British outlawed the trade. “What had been a place of torture and lack of dignity became a place where humans would be called to the ultimate dignity: redemption itself.” Yes, Lord, this very market—a blood–caked whipping post its fulcrum—became the site of the present church. There Thomas Cranmer’s prayers are inscribed in Swahili. “While there can be no doubt that Christianity was [at one point] used to justify the [slave] trade,” writes Butler-Gallie, “it was also by Christianity that the greatest blows were struck against it.” The coral rag that makes up the crenelated walls of this church, the message of cross and resurrection embedded within them, testifies to this inevitability. As William Wilberforce insisted, the enslaved, “instead of being an inferior order in creation, are even preferable objects of the love of the Almighty.” Wilberforce’s dying words expressed his hope that he had set his feet on the “Rock” of Christian faith, which he most certainly had.

Lord, save me from the timid science that, notwithstanding its restricted legitimacy, cannot bring you into its scope. Save me from the tremulous theology that shrinks from investigating coral. Save me from the tepid evolutionists, including the Christian ones, who make their sad pacts with death. Save me from antiquarian art history that brackets the questions here explored. Save me from unimaginatively wrought baptismal fonts and from forms of Christianity that notarize fatality. Save me from those who consider your gospel to be something less than the structure of the cosmos. Save me from anything less than the “mystery, which from the beginning of the world has been hidden in God, who created all things by Jesus Christ” (Ephesians 3:9). This gospel resonates in both caterpillar and coral, and sings from the stone in my hand; it is preached not only in pulpits but by the bones of a lost and ancient sea.

Note: Thanks to my geologist colleague Stephen Moshier for his assistance in discoursing on coral, and to Anthony Lappin for the reference to Czesław Miłosz’s poem “To Mrs. Professor in Defense of My Cat’s Honor and Not Only.”