O

On the night of April 19, 2022, at around 11:45 p.m., a stray bullet from a building behind us pierced our bedroom window and ate a chunk out of our hallway before coming to rest at the foot of the door. My wife and I were in bed, safely out of the bullet’s trajectory. I didn’t hear the actual gunshot; what woke us was the sound of the bullet piercing our window. Of the five shots fired, none seemed to have an intended target. No one was hurt, save some glass, composite wood, and plaster.

The morning after, I did what I often do to process—I picked up my camera. I made twelve images of the scene, exactly one roll of medium-format film. That night, I sat in my darkroom and developed the roll, let it dry, and took it to my desk to digitally scan and render the images. A bullet hole from a distance could be anything—a quiet menace. Sharing a frame with a bulging laundry basket, an unmade bed, and an under-watered monstera, the hole in the window almost feels like the next logical step in the disarray. At that scale, it could be anything. A benign accident. But as the crop tightens and the lens draws your face closer to what becomes more clearly an explicit trajectory, something shifts. What once might have fit its context can now be more clearly seen for the disruption that it was and is. It almost makes you want to duck. Looking at these twelve photos was the first time in the hours after being woken by the sound of the bullet breaking the seal between our double-pane vacuum-insulated windows that I felt fear. That sound of matter being pierced, not the sound of the gun’s violent outburst, is what haunts me. That’s the sound of these images.

I didn’t start thinking about the violence in photography’s practices and vocabulary until Trayvon Martin was murdered by George Zimmerman. Suddenly, the camera I was holding in my hand while walking Black down the street felt like a matter of life and death. The lived experience of most marginalized people around the world is that of being perceived in all the ways and places you’d rather go unnoticed and being invisible in all the places you desperately want to be seen. If the soft, colourful contour of a candy wrapper in the hands of a brown child can be perceived as a weapon so threatening as to cost him the adolescent breath in his lungs, then how much more might my six-foot-plus, 250-pound frame holding a cold, glimmering, black-steel mechanism that speaks the language of a weapon deserve the same?

The lived experience of most marginalized people around the world is that of being perceived in all the ways and places you’d rather go unnoticed and being invisible in all the places you desperately want to be seen.

Before Trayvon, I’d used the language of my craft without questioning it. I “shot” without much care or concern. I pulled a “trigger” thousands of times, “firing” a shutter and “taking” something that maybe was mine to take . . . though often was not. The language of photography, a phrase that became the title of a 2002 eight-part docuseries on the art, is most often understood to be a visual one. But indigenous peoples in many parts of the world believe that to take a person’s photo is to steal their soul. And in an era when more photos are taken in a single day than in all of recorded human history before the nineteenth century, I wonder if it might not be time to start asking some questions.

Camera Violence

The mechanism of photography under a microscope is more than a little vicious. A collage of released pressure, tension, chemical combustion, light, particle, molecule, and time collide in an instant to create something, almost like creation itself—a big bang at a human scale. No matter how many hours I spend in a darkroom, seeing an image I took a week ago come spooling out of the tank or watching a photo reveal itself in a development tray, it still feels like a miracle—every single time.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s heliograph camera, the first that we would recognize today as a camera capable of not only casting an image but also rendering it permanently on a surface, was invented in 1816, over four centuries after the first firearm. The term “shooting” didn’t become common parlance until about half a century later, when cinematography was just taking off. And then in 1965, Kodak Eastman introduced the Super 8 camera. Compact, affordable, and more accessible than its predecessors in the same format, the Super 8 suddenly made cinematography available to the hobby-curious masses and family documentarians.

It looked like a modern handgun. Previously, one operated a camera by cranking a lever that would turn the film in its spool. Suddenly, the Super 8 had a handle and a trigger. The spool’s movement could now be automated, only one human hand used, and instead of cranking a lever, it now simply had to pull a trigger. I wasn’t there, but it’s not far-fetched to imagine that filmmaking and image-making were reduced right then to simply shooting.

So what came first, the chicken or the egg? Before the camera, images were crafted by the human hand. The earliest renderings that we’ve been able to find of the human form perceived by another can be found on the walls of primitive cave dwellings in what is now Sulawesi, Indonesia. “Formal” portraiture finds its origin in ancient Egypt and has been used since to depict every facet of the human condition: strength, beauty, virtue, pain, affluence, even divinity. The work of image-making was slow. To render a likeness was to see it fully. To study and understand, subject and artist would spend hours together, locked agaze. It was an exercise in vulnerability, trust, and, in many cases, physical and emotional endurance. A likeness was given, an image was taken, and a portrait was made. Each step in that sequence had its process and mechanics. There were no shortcuts, only craft.

The invention of the earliest cameras didn’t see much change in the time and craft required to create an image. A scene was set, the subject brought in, studied and posed, light would be considered and reconsidered (because the sun stops for no one). Then, an image would be taken by exposing a reactive surface to the light. After exposure, the final image would be made by bathing that reactive surface in chemistry. Again, a likeness was granted to the artist by a subject, an image was taken, and a portrait was made. The mechanics were cumbersome and unreliable, and the chemistry was often unstable. A photographer was part engineer, part alchemist, but still entirely artist. The seeing that defined and determined the quality of a painted portrait was still fully present in this new craft.

But as with all technology, advancement brought with it the seduction of efficiency. Efficiency in the taking of a photo saw timers added to lenses to streamline the camera system. Single-use flash bulbs were created so we would no longer have to consider the sun if we didn’t want to—the natural replaced by the unnatural. The bulky iodine-sensitive wet plate that bore the subject’s image was replaced with a large sheet of light-sensitive plastic, which was soon replaced by a more compact, consumer-accessible film. The camera’s body, once a formidable, space-taking, human-scale sculpture in its own right, would, at that same time, diminish to about the size of a small boule of bread operable with a single hand. Suddenly, taking a portrait required little thought and almost no connection to the physical being of the photographer, save for the pad of her index finger.

At the same time, advancements in the photo-making process sprinted toward instant gratification and the removal of the image maker from the process. Wet plates became film but still had to be bathed in chemicals to produce negatives, which would themselves see another photo-chemical process before a photo was made. Then came the Polaroid, a novelty medium used at home to document the sentimental and in artist studios to test composition and light before the “real” portraits were taken. Polaroids and instant paper mediums removed the need for a negative but still bore a keen resemblance to the craft by containing the paper and chemistry all in one—just add light and time.

To this point, a photo was still something you held, hung, and pressed into albums that you’d visit once a year around the holidays. And that remained true until the revolution when analog met digital, and the world would be changed fundamentally forever. Now not only were we free to “create” without making, but the product of our creation could live and die without ever being touched. Again, the camera shrunk, and the mechanism of making disappeared entirely. Soon the whole thing, the taking and the making, would be compressed into a phone—becoming one of a thousand different functions to engage with and never understand. We’d slowly become gluttons of images, with access to more pictures than ever and an exponentially diminishing capacity for seeing one another or the world around us.

Craft over Efficiency

Watching the first four parts of season 6 of The Crown, which documents the final, tragic days of Princess Diana’s life, it’s impossible not to be struck by the violence of the paparazzi wielding their weapons of the first content war. Weapons that can, at least partially, be credited for her torment in life and untimely death. The world watched—and continues to watch—as a never-ending barrage of cameras invaded the private lives of a person who we can conveniently other by labelling as a “public figure”—a cheap justification for a torment that often comes at a grave cost to the tormented. The right to privacy only became something worth debating when we developed the means to so quickly and effectively violate it, no? I chuckle when I imagine those same paparazzi chasing Diana around the world with easels, brushes, and palettes in tow, or with unwieldy large-format cameras, forced to see and be seen by their subject. Making images, not simply taking pictures. Those pictures couldn’t be taken with one hand while riding on a motorcycle chasing a doomed Mercedes sedan through the streets of Paris.

I’m inclined to apologize before waxing poetic about a nostalgia I never actually lived. But I won’t. I was born in 1990, at the dawn of the digital age. I have few conscious childhood memories of analog cameras, and my earliest meaningful engagement with technology was digital. My first film camera was given to me in 2017—a Canon AE1.

Craft doesn’t allow us to assume truth, but invites us to pursue it in the exercising. It sacrifices efficiency for the sake of understanding.

Since then I’ve sold off all my digital camera gear and continued to learn the craft of making photos, even stepping into the wildly expensive and torturous world of large-format photography. I’m working to be more conscious about the language I use when I refer to the process, not because I’m an insufferable hipster—though I am—but because I’m coming to believe that perhaps the opposite of this type of violence, maybe any violence, is craft—an exercised skill in making or engaging with something by hand.

Craft as an antidote to violence is a silly notion. As I write this, the widow, orphan, and marginalized are being systematically snuffed out by powers in Sudan, Ukraine, Russia, Palestine, and Israel, and in lesser-reported tragedies all over the world. I’m not so foolish as to believe that all that pain might stop if we replaced our digital with analog. Or perhaps, in some way, I am. Craft requires time. Time to learn, to fail, and most importantly to see with all our senses. Craft doesn’t allow us to assume truth, but invites us to pursue it in the exercising. It sacrifices efficiency for the sake of understanding.

In January of this year, I decided I wanted to engage with music differently. I wanted to listen to music as its own activity, not just as the soundtrack to my everyday goings-on, or what I’ve come to call vulgar listening. I began by sitting down to listen to an entire album every night before bed. Sacrificing my one more episode of whatever streamed show I had been mindlessly binging, I would sit in the same spot in my living room, select an album, and hit play. I started streaming the music on Spotify at first. It was efficient, and I have nearly all the music in space and time at my fingertips. But I’d inevitably get pulled away from my active listening and sucked into an algorithm that presumes to know me better than I know myself. So, I decided to limit the music I’d listen to in this protected time to records I own on vinyl—again, not just because I’m an insufferable hipster. I found that my capacity for listening, for fully seeing the music with my ears, increased tenfold. A craft of listening developed a ritual that engaged my whole self, a full-body meditation.

A similar practice has emerged in my photography. In 2021 I was fortunate enough to stand up my first solo show at a private gallery in Washington, DC. The show was titled Objective and turned out to be more of an exhibition of process than of the photos themselves. For six weeks I invited strangers into a room filled with beautiful, mundane, and monumental objects on display, as in a sculpture gallery. Each object was sourced from a member of my community of artists and creative misfits in DC, and sat on its own lit pedestal with its portrait and narrative displayed. In the centre of the gallery, as others engaged with objects on display, each guest and their artifact was photographed while telling their story. It was a fully analog process to create a portrait of our beloved community bound together by objective (literal object based) orienting truths, not divisive ideas.

Each portrait—one single photograph—took approximately twenty minutes to take. A stranger would approach me with an artifact in hand, and we’d exchange introductions. I’d offer them a seat, then step beside my camera to compose the image. As the composition came together, I would ask them questions about themselves and about their artifacts, working to see them as fully as time would allow. Before we were finally set for the photo I’d release the shutter a couple times, often wasting one or two frames of film, to allow them to acclimate to this foreign object and its formidable blink. Photographers often refer to workflows like this as “disarming your subject,” but I don’t see it that way. It’s rather inviting a person to create with me. At the start we’re strangers: a photographer and a subject to be photographed. But when it works, by the end, we’re both some form of medium for the art, as if somehow I’m the brush and they’re the paint, though at other times the opposite might feel true. Somewhere along the way, we slide into a fluid synchronicity, working together at the hands of a greater artist creator to affect the canvas in the camera.

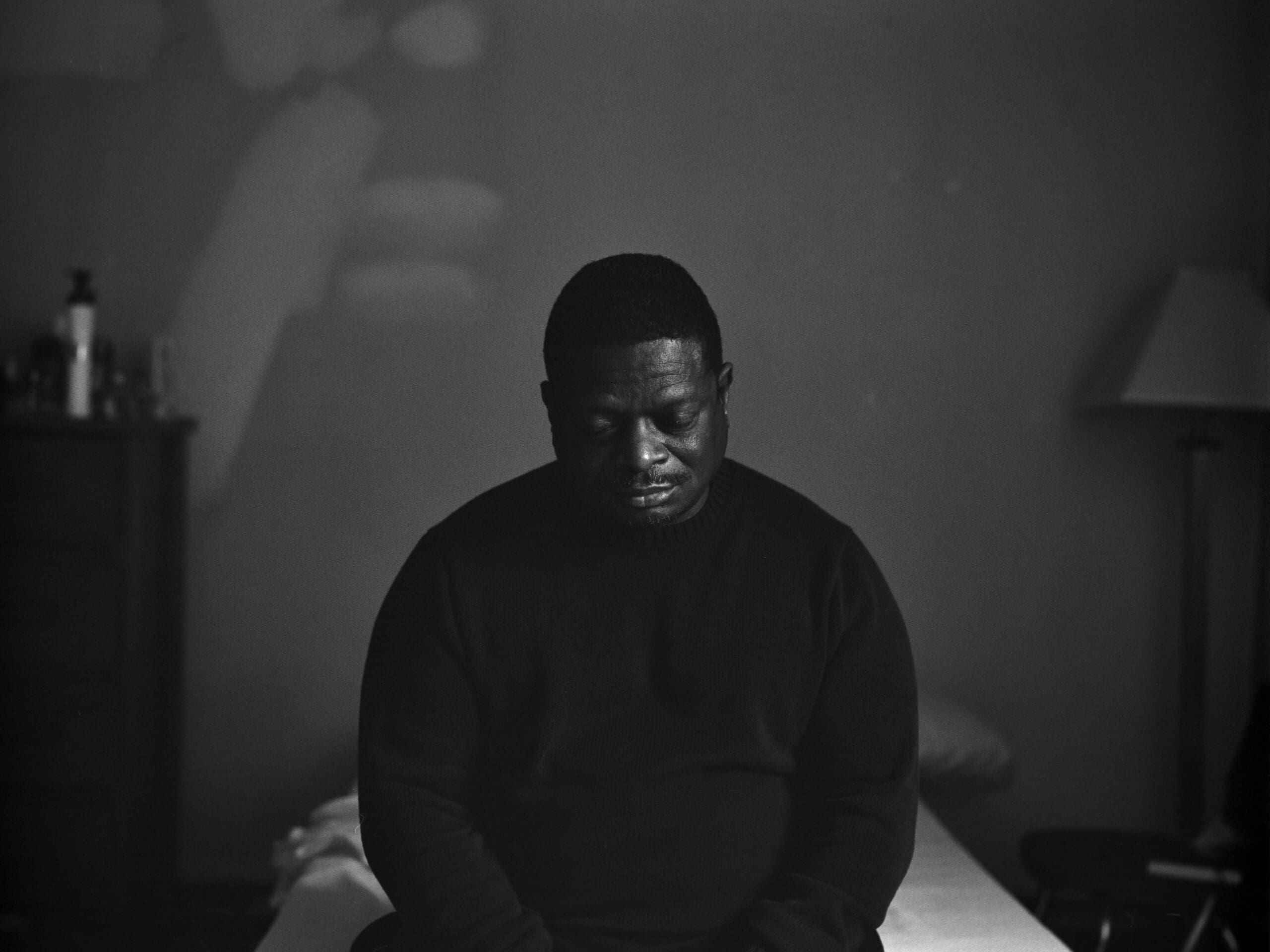

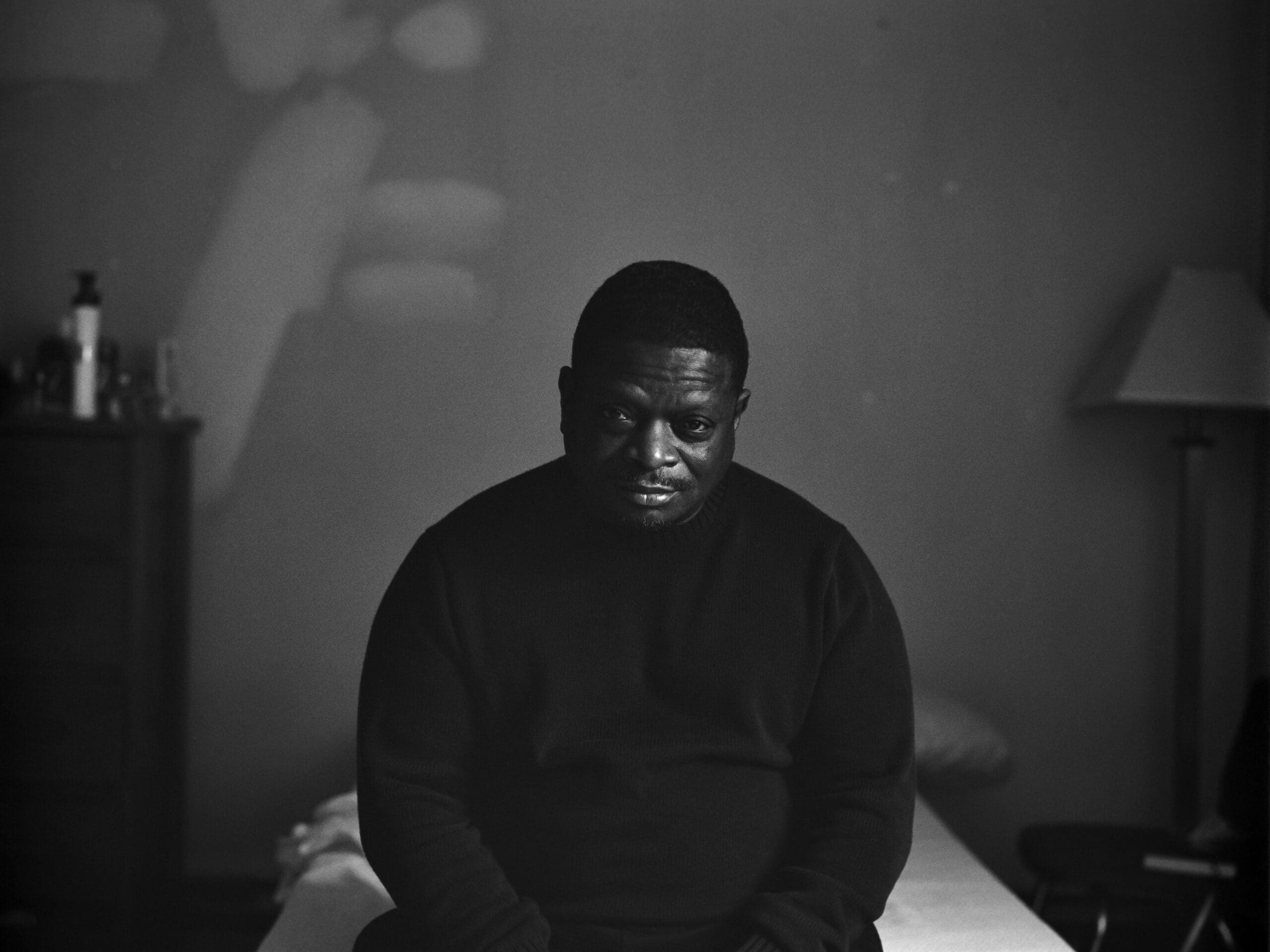

Day one of this process was painfully awkward for me. Now it’s become the only way I know how to work. I am the creative director of BitterSweet Monthly, a platform for human-centred, hope-building storytelling. Shortly following the experience of hosting the Objective exhibit, I travelled with colleagues to Ohio to create a multimedia piece about Y-Haven and the Cleveland Public Theater, who work to empower and heal the formerly unhoused and neighbours recovering from addiction through programming in theatre arts. I found my orientation to the camera had transformed. I wanted to test the power of slowness, not for slowness’ sake but for the sake of bringing each stranger along with me and ultimately letting them lead me.

I’d sit and listen for ten to twenty minutes of each person’s interview, my camera set aside. Then I’d introduce the camera in the same way I’d introduce the subject to a new friend—gently, warmly, an invitation to trust. In the listening, I’d pick up a pattern: Each artist we were featuring in this story had to draw into themselves to reconcile their own stories before presenting them in any authentic way on a stage. So I’d invite them to close their eyes and reflect briefly on how far they’d come. Then, given some of the practices from Alcoholics Anonymous this particular program employed in its addiction-recovery work, I’d invite them to say the Serenity Prayer to themselves and to open their eyes after. I’ll never know what image each person held as they walked through the silent exercise with me, but I do know that I’ve never made portraits painted, by light, more in the image and likeness of these strangers turned co-creators.

Recovering Wonder and a Non-violent Practice

Popular exercises like street photography don’t interest me in part because I don’t feel they’re available to me in the public square—again, being big and Black and rarely unnoticed. But I also feel like this kind of voyeurism embodies and enables the very violence we are all trying to escape. In her 1977 book On Photography, Susan Sontag says this:

Photography has become one of the principal devices for experiencing something, for giving an appearance of participation. One full-page ad shows a small group of people standing pressed together, peering out of the photograph, all but one looking stunned, excited, upset. The one who wears a different expression holds a camera to his eye; he seems self-possessed, is almost smiling. While the others are passive, clearly alarmed spectators, having a camera has transformed one person into something active, a voyeur: only he has mastered the situation. . . . Taking photographs has set up a chronic voyeuristic relation to the world which levels the meaning of all events.

Here is Sontag nearly fifty years ago proposing a worldview that sees the photographer as a passive observer at best and a tacit enabler at worst. Even she could never have predicted the extent to which that observation would prove true as the camera would become more ubiquitous and accessible than health care. We celebrate “creative” destruction nowadays as a badge of progress. But all I see is the tragic predictability of human beings turning a gift meant for creation into a tool of destruction. Surely we can do better.

The way of craft does not depend on the analog. But in a world hell-bent (maybe hell-bound) on becoming more efficient every day, perhaps the only way to boomerang us back to craft is with an intentional detox of the efficient, connected, and optimized. The way I’ve chosen to make photos in film has fundamentally altered the way I make photos on my phone. The way I’ve chosen to forgo vulgar listening has changed the way I engage with Spotify. I still live in this world, in this time, just slower and on purpose. Pete Holmes, comedian and self-described mystic, has a whole bit about hating the navigation app Waze. “[Waze] is not the way of the soul,” he says. “It’s all head and no heart. Do you know what I mean? It just sucks you in and you’re just like ‘TRAFFIC? HA! we’ll see about that!’ . . . I don’t need to save five minutes careening through gated communities.” On a recent episode of The Adam Carolla Show, Holmes expands on the bit by explaining that all such smart GPS apps exploit the worst of our human impulses to avoid surrendering to and being present in whatever moment we’re in. I couldn’t agree with him more.

I have this photo of my grandma. We called her Granny. It was taken somewhere in Nigeria in the late sixties on some type of instant-sheet film. It’s framed and hanging by the front door of our home. Before I framed it, I’d often sit holding it. Looking at Granny’s face, I’d find myself getting emotional almost every time. Photosensitive instant film, like all film and even the digital camera sensors of today, uses the light in any given scene to render an image. But unlike other mediums, the paper renders the final image. That means that the light touching and contouring my grandmother’s cheeks in the photo is the same light that permanently etched her face into the paper I’m holding. Sometimes when I’m holding it in my hand, it feels like I’m somehow physically connected to her standing in another place and time. That piece of paper—that crafted photo—feels like a miracle.

This creative life isn’t about some technophobic or Luddite-like posturing. It’s not about being an insufferable hipster, though I might be. It’s about removing from our lives, for a moment, the things that entice us to move fast for fast’s sake, and in their place find ourselves connected to a world of wonderment far greater than we could ever hope to understand in a lifetime, one that is too miraculous not to explore. A material playground of cosmic origin built as the penultimate expression of love from the divine to us image bearers. Craft is getting lost and finding something you didn’t know you were looking for. It’s an opportunity to ask yourself why you’re doing what you’re doing, an invitation to understand how what you’re doing is being done. Perhaps most importantly in a life committed to non-violence, it will develop a conviction within you to ask who might be affected by what you’re doing and in what ways. It’s a way, maybe, to mitigate some of the unintentional violence we’ve inflicted on our social fabric in the name of innovation. Craft is asking the stars why it took seven days to create creation, when God surely had the means to do it in one.