So many of us have felt dread, that inchoate sense that something isn’t quite right: not with our politics nor our country nor even, perhaps, our own souls. We don’t often have the language for that thing, whatever it is, but the inability to give that something a name is perhaps what makes it so ominous. It’s a foreboding that has built vaguely if steadily over the past several years, reaching its culmination in one political event—our presidential election. And now, after the verdict, it may be time to try to pick up the pieces, to use the cliché commonly associated with days after and societies divided. Before beginning the work of rebuilding, however, it may be worth asking whether the premise is correct. Are we actually broken? And, if we are, do we need to be put back together?

* * *

This is an odd time, and so I have found myself feeling odd about my own politics. The last four years, if we wish to mark the passing of time by our presidents, have rushed over me largely as a relief. It could have been better, but it also could have been worse, maybe even much worse. In December 2015, I remember a conversation with my parents, something akin to the Muslim version of “the talk.” Donald Trump, who was an insurgent candidate then, found himself intrigued by the idea of registering Muslims in a database. He was unable to disavow President Franklin Roosevelt’s internment of Japanese Americans. We played out the worst-case scenarios, and half jokingly but also half seriously, my father reminded us that he still held Canadian citizenship. We had a backup plan.

American democracy, however, did not die, even if it finds itself in far from perfect health. And American Muslims, despite rising Islamophobia (or perhaps because of it), were embraced by one of the two main political parties for the first time. By propelling “us” to the top of his agenda, Trump, with his various Muslim-focused travel bans, inadvertently made us an integral part of the American story. And we had a sort of coming out, with Muslim comics, actors, congresswomen, and even Muslim sitcoms entering the cultural mainstream.

Of course, we find ourselves still a nation divided, even if it feels more divided than it actually is. (The more one follows politics closely, the more hopeless it seems.) The differences are existential and relate to foundational questions of identity, culture, and religion. Americans no longer agree, if they ever did, on what it means to be American. Since the United States is a credal nation that cannot fall back on shared ethnicity or a common sense of space and time, these divides, once activated, do not easily subside.

It is difficult to split the middle on the “who we are” questions, because it is difficult to change who we are. But it’s not clear that we even should change who we are. The United States is an increasingly diverse country, and diversity is difficult. There are several ways of dealing with deep difference: as a problem to be solved or as a fact to be managed or, more optimistically, as something to be appreciated, maybe even celebrated, because difference, however deep, is an expression of God’s will. If we are broken, it may be better to live with that brokenness and do so as productively and peacefully as we possibly can.

When faced with problems, Americans tend to prefer solutions over uncertain accommodations with imperfection. Our political optimism has its dark side, making us both hopeful about overcoming differences but unforgiving when those same differences refuse to be flattened. And so it is apt that a Dutch pastor, largely unknown in the English-speaking world, might help us understand how to live with our broken pieces. In this reading, the pieces do not need to be picked up.

* * *

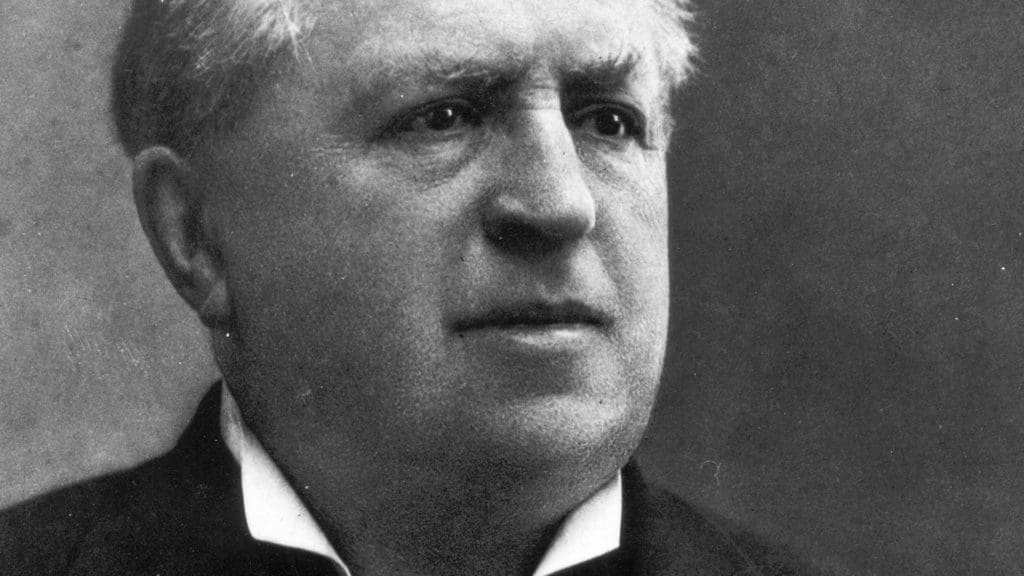

Abraham Kuyper was the rare theologian-politician—and the rare Calvinist—whose electoral calling met with some success, serving as prime minister of the Netherlands at the turn of the twentieth century. Born in 1837, he was, and remains, the preeminent ideologue of “Christian pluralism.” His political convictions were founded on a fundamental, if austere, theological premise, one that flowed from an emphasis on God’s sovereignty rather than the more traditional Protestant framework of justification through faith alone (sola fide). Unlike other twentieth-century thinkers known for their preoccupation with sovereignty, such as the radical Islamist thinker Sayyid Qutb, Kuyper’s sovereigntism led toward, not away from, political and intellectual modesty. If God was sovereign, it only made the contrast with mere men more striking. And those men, particularly when they were tempted by power, couldn’t be trusted to speak in God’s name.

Men (and women) are sinners. In Our Program: A Christian Political Manifesto, published in 1876, Kuyper writes, “If humans are sinners, there can be no question of deriving the eternal principles of justice from their sinful minds.” Once sin enters into human consciousness, direct access to divine intent becomes impossible. This, in turn, makes theocracy an affront to God’s sovereignty. One can search for and even find the will of God and live according to it, yet this discovery will be imperfect, and attempts to “execute” that will—in public as well as in private—will always bear the marks of sin. Because of sin, the sinner, however righteous, cannot know God’s will with certainty.

How does one elevate an appreciation of temporal uncertainty into a call to arms? It is not easy. And, needless to say, recognizing sin and sinfulness is out of fashion.

This theological argument, common if somewhat obscured in the monotheistic faiths, did not stand alone. It was sharpened and amplified by the realities of Dutch politics in the nineteenth century. Kuyper was a product of his time, and he was pragmatic. As he declares in Pro Rege, perhaps the closest Kuyper would ever get to a battle cry: “[Our reforms] do not divide the nation or break society. . . . They find the nation divided, conviction against conviction and they reckon with undeniable fact!”

In much of Western Europe, the first half of the nineteenth century was something like a continuous shock in the shadow of revolution. The unforgiving anticlericalism popularized by France’s revolutionaries meant a more diverse and divided society. Where there were once only Christians, split between Protestants and Catholics, now there was a patchwork of avowed secularists, humanists, liberals, and socialists. Accordingly, Kuyper also made a straightforwardly practical argument against theocracy: There simply weren’t enough Christians—and certainly not enough Calvinists—for theocracy to be viable. And even if there had been, more and more Calvinists found their faith wanting due to the spread and normalization of secular ideas.

Religious government required buy-in from the members of a given community, or in this case a much larger nation. As Kuyper wrote, “Theocracy is only possible when everyone voluntarily agrees with the theocracy but this is very rare.” Therefore, “a Calvinistic utopia is out of the question. There is only a Kingdom of the Netherlands as this factually exists in the second half of the nineteenth century.” Unity, however desirable in theory, was in direct conflict with diversity, in practice.

A theological premise coupled with Dutch political realities allowed a rich pluralism to be imagined—and to some extent built. And it was built on sin. Sin, in turn, made its demands. If the city of man was inherently broken and fallen from sin, this meant that politics was a site of uncertainty rather than certainty. Perfection was possible, but it was not possible here. It would only come with the return of Christ. As the theologian Matthew Kaemingk writes in Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear, “True Christian pluralists release the reigns of national history. . . . Any effort to preempt Christ’s unifying work, any effort to establish an immanent universal sanctuary on earth was completely out of bounds for those who recognized Christ’s temporal sovereignty.”

In the meantime, until Christ returns and heals the divisions born out of the brokenness of man, there will be a multiplicity of faiths and ideologies. Kuyper often referred to these ideologies as “all-embracing life-systems,” prefiguring today’s understanding that secular ideologies, however opposed to religion they might seem, often mimic traditional religion’s attributes—including sin, atonement, and punishment—but in the service of a different soteriology.

This multiplicity of duelling visions of the good life, as divisive as it might seem, was not something against which to wage battle. If God had willed everyone a believer, it would have been done. But, instead, “ideological fragmentation and division is simply the reality of life lived after the fall into sin,” as Kaemingk explains. And it wasn’t necessary to lament what could instead be accepted and perhaps even appreciated, however difficult that might be.

* * *

For the non-Calvinist, the preoccupation with “the fact of sin”—a sort of organizing principle for Kuyper and the Christian pluralists—might seem both odd and dour. And this may explain why Christian pluralism, even among Christians, remains more of an intellectual curiosity than a fighting faith. How does one elevate an appreciation of temporal uncertainty into a call to arms? It is not easy. And, needless to say, recognizing sin and sinfulness is out of fashion.

Kuyper’s insights here, however, transcend their Christian origins. They may be grounded in a believer’s conviction, but they are well suited for any polarized society, whether it be the Netherlands in the nineteenth century or the United States and other Western democracies today.

If politics—like everything fleeting and finite—is a site of uncertainty because it is a product of human endeavor, then this has wide-ranging implications. We do not need to call it sin. In principle if not necessarily in practice, most people grasp that the human capacity for total and true understanding is circumscribed. We know that even the most intelligent and self-aware betray cognitive biases that are difficult to overcome. We know that they act irrationally, if nothing else because we know that we act irrationally in our personal lives, in matters of love and friendship for instance. This isn’t sin, necessarily, but politics, like any emotional enterprise, is prone to these bouts of irrationality, and it requires humility.

If none of us are immune to misperception, questionable judgment, and other lapses of flight and fancy, then it follows that we should hope there are no final victories in this life. Even if the most “righteous” among us gain political power, they are, or will be, flawed nonetheless, so there should always be clear and regular mechanisms for removing them. The desire for power is both understandable and unavoidable, but the desire to dominate the other side, whatever that other side is, should always be seen as suspect. Applied to American politics, the liberal left should not wish to conclusively defeat either conservatives or the Republican Party, through the accumulation of political power in addition to the cultural predominance it already enjoys. The language of permanent majorities is a sign of this excess.

Abraham Kuyper was naturally suspicious of majorities. By the late nineteenth century, faithful Calvinists were a minority. Rather than being neutral, an increasingly powerful Dutch state embarked on the ideological project of liberalizing a formerly religious society. As Matthew Kaemingk notes, the new liberal nationalism was shot through with something resembling religious fervour. Education became a primary battleground. In forging a modern nation, governments, through the standardization of school curricula, had an understandable interest in weakening primordial identities. The fears were, once again, tied to the legacy of the French Revolution. As Georges Danton, the first president of the Revolution’s Committee for Public Safety, memorably put it: “The time has come to establish the principle that children belong to the Republic before they belong to their parents.”

Kuyper’s posture was essentially defensive, wishing to stand athwart history. Just as Christians had been strange, they would become strange once again. In Lectures on Calvinism, he writes that “authority over men cannot arise from men. Just as little from a majority over against a minority, for history shows, almost on every page, that very often the minority was right.” As a factual matter throughout human history, particularly during its darkest periods, this is true, but as a recipe for democratic politics—based as it is on majority rule—it doesn’t necessarily inspire confidence. This minoritarian perspective is in keeping with Christianity’s early centuries, during which Christians lived as minorities and were not in a position to govern themselves, or for that matter anyone else. Interestingly, in Islam, there is a well-known hadith attributed to the Prophet Muhammad that “my community will never agree upon an error,” which has often been by used modern Muslims as a retrospective, if overly convenient, justification for democracy.

A conception of democracy centred on sin can’t help but be different. Kuyper’s understanding of the contingency of one’s place in the majority or minority is vital for a democracy in which diversity overcomes the possibilities of unity. And that is the nature, for better and worse, of most Western democracies today. Short of coercion or expulsion, diversity cannot be undone. The question, then, shifts to how pluralism might emerge out of mere diversity. Learning to live together because of deep difference, rather than in spite of it, is not a natural way of thinking about or practicing democracy. It must be learned. Or it is a decision that must be made.

A conception of democracy centred on sin can’t help but be different.

If only God knows, we cannot. This might sound like one step too many toward moral relativism. But this would be a misunderstanding of Kuyper, who was anything but timid. In his own way, he was quite zealous. Kuyper—like all orthodox adherents of the two universalist faiths, Christianity and Islam—believed in one account of the truth over others. It was only a question of who would judge and when judgment would come. It’s not so much that judgment was suspended. Rather, it was postponed, allowing for some relief in the interim. For the believer, judgment presumably comes, but it comes later. For those who do not believe in God, it simply won’t come at all. Regardless of their faith or lack thereof, citizens can consciously choose to resist making mundane politics tantamount to the sacred. This is not doctrine, and this is not forever.

We believed we could be one, but we are not the same. And perhaps our mistake was thinking that we ever could be. This country—like most countries in an era of growing ethnic, cultural, and ideological diversity—is one that contains within it irreconcilable conceptions of the good. Rather than searching for a reconciliation that may never come, now is a time to be broken.

Image: A Corner of the Rose Garden by Berthe Morisot, 1885.