A

As an art historian, I figured it was time I learned for myself whether images generated by artificial intelligence programs constitute a revolutionary advance or just an accelerated manifestation of humanity’s insatiable, misdirected desire. So after signing up and paying a small monthly fee, I was thrown into a beginner’s room for AI image generation at Midjourney. It was a headfirst dive into the collective unconscious. I was immersed in a stream of images: idealized childhoods, Pixar-style family barbeques, personal coats of arms, bearded bartenders with bulging biceps, and idealized World War I battlefields. Images of stereotypically hot women and men were followed by a plate of hot wings appealing enough to activate my salivary glands.

I looked at the prompts to see how these images were being generated. One said, “The Heisenberg character from the series Breaking Bad looks into the distance, standing waist-deep in money.” Another requested an image of “financially free woman, travelling, looking from a mountain top.” Then came requests for a “sasquatch rainbow chair throne,” an “angelic figure of an older woman watching her lover die,” and “a photo of a LGBTIAQ+ trans magical girl.” Soon, however, the magic began to wear off. “The right response to Eros,” claims Malcolm Guite, “is to ask not for less desire but for more to deepen my desires until nothing but heaven can satisfy them.” If anything, the desires these artificially generated images were aiming to satisfy didn’t seem nearly deep enough. The cataract soon elicited my compassion.

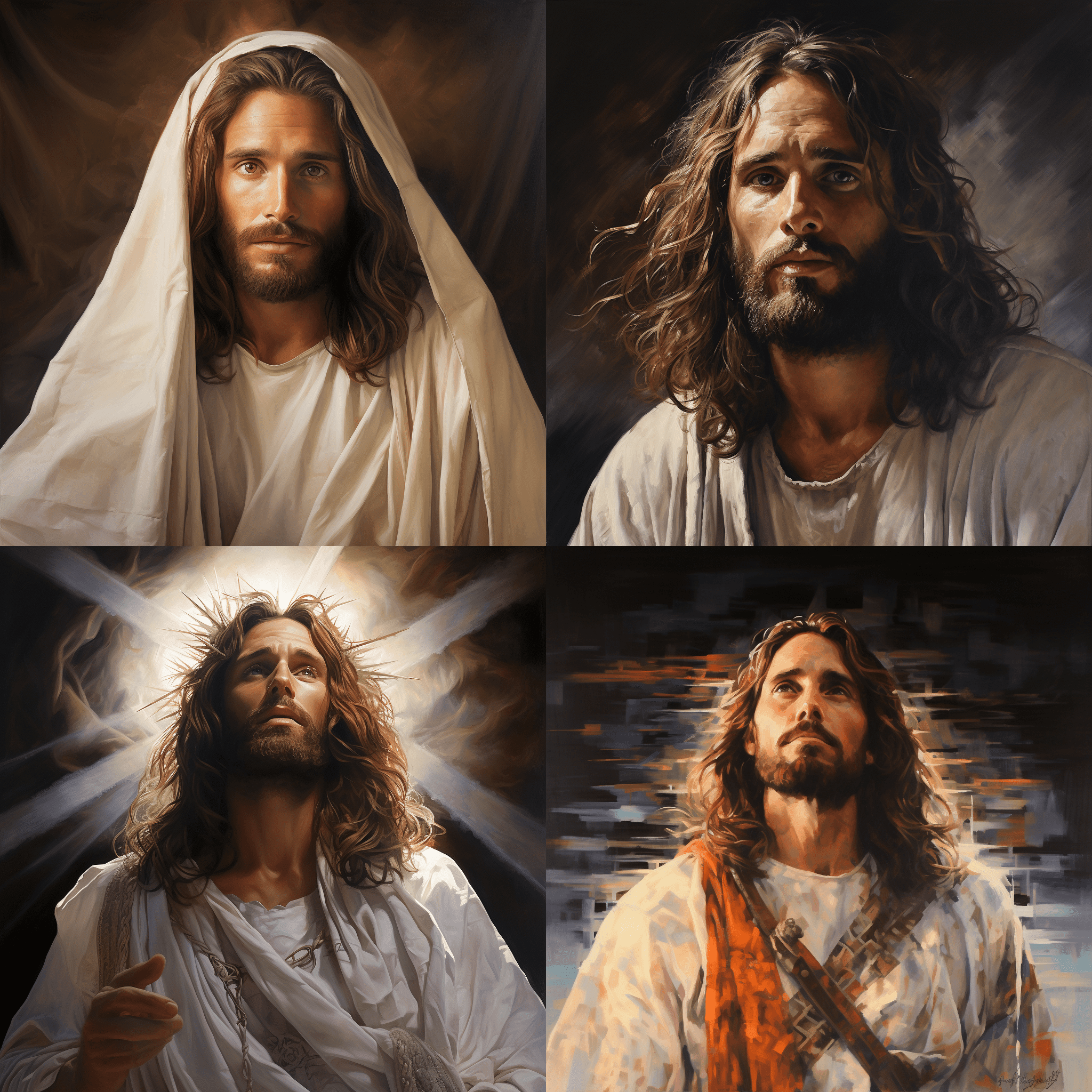

Still, I had come to Midjourney to attempt something good. A friend at my church, a University of Chicago computer science graduate student and senior editor at AI and Faith, is using this technology to achieve breakthroughs in Bible translation. He urged me to look into AI’s iconographical potential. My colleague Richard Gibson similarly counsels us to “preserve old practices and to implement new ones.” That’s why I was here. I quickly discerned that the theological wisdom of AI is rather limited. My former colleague Beth Jones has done a fine job of showing these limitations, and my sojourn with Midjourney did not do much better. Unguided prompts for “God” simply defaulted to comic-book motifs of pagan gods and goddesses. Midjourney’s images of Jesus Christ, moreover, defaulted to biblical illustrations from the 1950s.

Still, I teach Renaissance art, so I couldn’t give up that easily. Faced with new developments like one-point perspective and oil painting, some forcefully resisted (the Dominican preacher Savonarola comes to mind) and others enthusiastically embraced the new methods (Leon Battista Alberti, Fra Filippo Lippi, or Bronzino). Yet others found faithful ways forward while still holding to traditional Christian wisdom (such as Fra Angelico or Piero della Francesca). Hoping to pursue this third way, I aimed to deploy AI to recover a lost ancient African saint, whose existence is evident enough but whose writings have been misunderstood for centuries. There is no iconography of this saint that I am aware of—no tradition to draw on. So I wondered: Could AI help? Before I recount the results of this experiment, let me introduce you to this forgotten saint.

Introducing Aphou

In the first few columns of Material Mysticism, we examined the life of Evagrius of Pontus and the way his tradition of imageless prayer has been visualized. But instructive as this tradition is, its emphasis came with a cost. When Evagrius’s disciple John Cassian brought this understanding to the Latin West, he cast Evagrius’s imageless form of prayer as superior to the contemplative practices of indigenous African desert simpletons. The standoff between the two parties is known as the Anthropomorphite Controversy, and it is worth examining in detail, especially as it is so frequently misunderstood, even by scholars who should know better.

John Cassian is not the only figure who mentions this famous desert row. The Christian historian Socrates (380–450) relates that while those allied with Evagrius prioritized imageless prayer, “more simple ascetics” took the position that God had a human form (hence “Anthropomorphites”). Socrates tells us that Bishop Theophilus of Alexandria (384–412) initially attacked the Anthropomorphites and chose the Evagrian side of the dust-up in his festal letter of 399 (the year of Evagrius’s death). But faced with opposition from the “simple Egyptian monks” who threatened to kill Theophilus in protest, the bishop relented. According to Socrates, Theophilus pacified the angry mob of monks with the words “In seeing you I behold the face of God.”

But there are competing accounts of this dispute, and this is where the lost African mystic Aphou comes into play. Another source beyond Socrates, The Life of Apa Aphou of Pemdje, came to light in 1883. This biography relates that Aphou, a so-called Anthropomorphite monk, waited three days to gain an audience with Bishop Theophilus. Thereupon Aphou successfully convinced Theophilus to change his position. The Life of Apa Aphou (freshly translated here) suggests that Theophilus, rather than caving in to popular pressure, was properly convinced by superior reasoning. This work has caused several scholars to conclude that Socrates and John Cassian offered exaggerated accounts, and that the real issue at hand was the image of God in humans, and on this point the Anthropomorphites were rightfully resisting Origenism, which sometimes hesitated to assign to humans the image of God.

In the same way that Evagrius’s theology has been rehabilitated through careful scholarly efforts, the detective work of several scholars—Paul Patterson most recently—has rehabilitated the Anthropomorphites as well. As a result, no longer do they appear to have simplistically imagined that God had a literal body. Instead, they appear to have been following an older, esoteric Jewish tradition that enabled the sight of God in qualified fashion. After all, the prophet Ezekiel saw “seated above the likeness of a throne . . . something that seemed like a human form” (Ezekiel 1:26). This in turn was linked to Genesis 1:26–27, the locus classicus for humans bearing the image of God. This tradition of God’s body was carried into the book of 2 Enoch 39: “You, you see the extent of my body . . . but I, I have seen the extent of the Lord, without measure and without analogy.” Such discoveries mesh beautifully with recent studies that show the “overwhelmingly visual nature of religious experience in Jewish spirituality.” In fact, I can think of no better illustration of Aphou’s Christology than the image of the logos incarnandus (the Word to be incarnated) in the Florence baptistery we examined last time.

The Anthropomorphites offered a visual way of arriving at the Nicene assertion that Christ was “born of the Father before all ages.”

In short, these “Anthropomorphites” retroactively understood Jewish intimations of divine physicality as intimations of Christ. It is not that the Anthropomorphites were against the emerging consensus regarding Christ’s divinity established at the Council of Nicaea. Rather, the Anthropomorphites arrived at Christ’s divinity in other ways and were slower to become aware of the imperially sponsored doctrinal settlement. They were imagining something perfectly valid: the divine, pre-incarnate “body” of Christ the Lord. It was a visual way of arriving at the Nicene assertion that Christ was “born of the Father before all ages.” The Anthropomorphites testify to deep visual Christology that precedes and anticipates church councils (such as the Seventh Ecumenical Council in 787).

In other words, while it may be the case, as David Bentley Hart argues, that “members of the Nicene party [such as Gregory of Nazianzus and Evagrius] were the daring innovators, willing to break with the past in order to preserve its spiritual force,” there was an older and more traditional visual Christology that supported Nicaea, however exotically sourced—namely, the Anthropomorphites. And this earlier confirmation of Nicaea in fact proves Hart’s point that “Christianity grew and endured and even flourished over the course of many generations in total and blissful ignorance of any officially defined dogmas [of Christendom].”

As Alexander Golitzin puts it, these so-called Anthropomorphites “may well have been ignorant simpletons, but if so, they were simpletons in defense of traditions that were much older and more sophisticated than they.” In sum, the Anthropomorphite Controversy now appears to reflect two sides of a diverse trinitarian tradition—the one imagining the body of the pre-incarnate Jesus and the other focusing on the God who is beyond images altogether as a matter of practical prayer.

Aphou, Race, and Indigenous African Faith

Thanks to the new light shed on this controversy, Aphou emerges as a hero of ancient Christianity as worthy of celebration as Evagrius. And while it may be the case that contemporary scholarship frequently overemphasizes race, when race is a factor in a theological debate, it should not be ignored. And race certainly plays into The Life of Apa Aphou. “How can you say of the Ethiopian man that he is the image of God?” the politicking Bishop Theophilus asks Aphou, “or of someone who is leprous or lame or blind?” The question posed to Aphou betrays an understanding of dark skin as a defect.

But what is amazing in this text is how well Aphou comes off even from modern standards of racial sensitivity. While Theophilus assumes Ethiopian inferiority, Aphou defends Ethiopians. “And concerning the variety of illnesses, [skin] colors and deficiencies that are in us . . . on account of our salvation, none of these can in fact disgrace the glory which God has given us.” Like Gregory of Nyssa’s attack on slavery, Aphou defends the universality of the image of God in the face of Theophilus’s refusal to do the same. We could add that Aphou’s listing skin colour among defects is not to say that he endorses this categorization but that he is reflecting Theophilus’s assumption and resisting it in no uncertain terms.

Like Gregory of Nyssa’s attack on slavery, Aphou defends the universality of the image of God in the face of Theophilus’s refusal to do the same.

But there are what we might call indigenous aspects in The Life of Apa Aphou as well. Theophilus, impressed by his answers, wants Aphou to be bishop, but Aphou’s response—like any sane person faced with administrative prospects—is to hide. When Theophilus’s emissaries go to find him, they encounter local Africans who betray his hiding spot in the desert with the antelopes. In a scene that is reminiscent of Cuthbert, the Anglo-Saxon monk whose feet were warmed by otters as he prayed, Aphou is sustained by these animals. They shield him from the sun in the heat, and they breathe on him in the winter. When Aphou is caught, he shows more concern for the antelopes he is hiding with than for himself, insisting they release his creature companions. The echo of John 18:8, “If you seek me, let these men go,” is unmistakable.

Aphou finally assents to episcopal leadership, but he negotiates an arrangement that allows him to continue living among the antelopes, intimately connected to the land and its creatures, while doing his episcopal work on Sundays. In his book Indigenous Theology and the Western Worldview, Randy Woodley avers that we need to be on the lookout for moments in the Christian tradition where animals appear and where connections to the earth are evident. If this episode in The Life of Apa Aphou is not one of these moments, I don’t know what is. If “wild Christianity” is what we’re after (as Paul Kingsnorth and Michael Martin insist), you can’t do much better than the African Aphou among the antelopes.

AI and Aphou

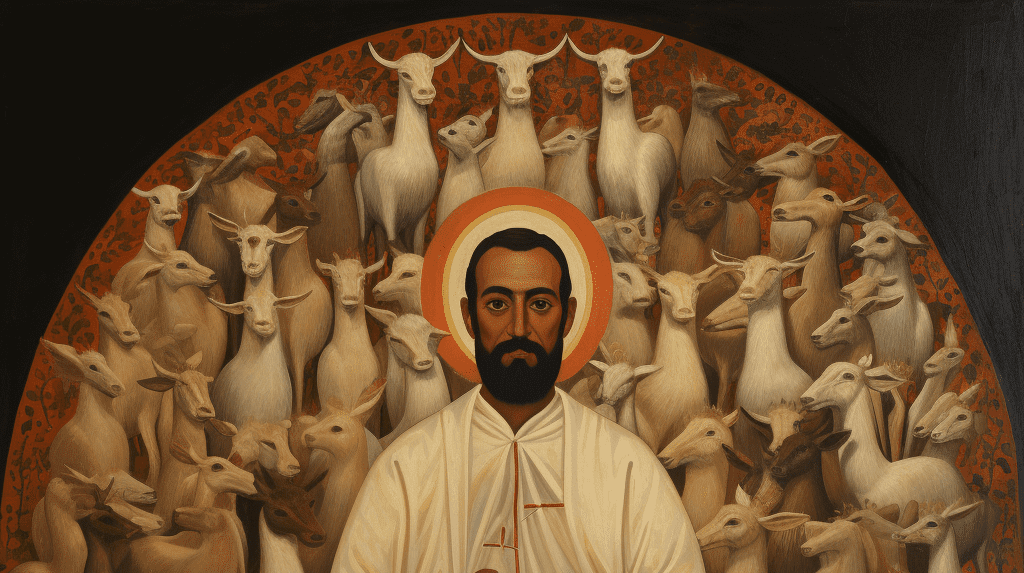

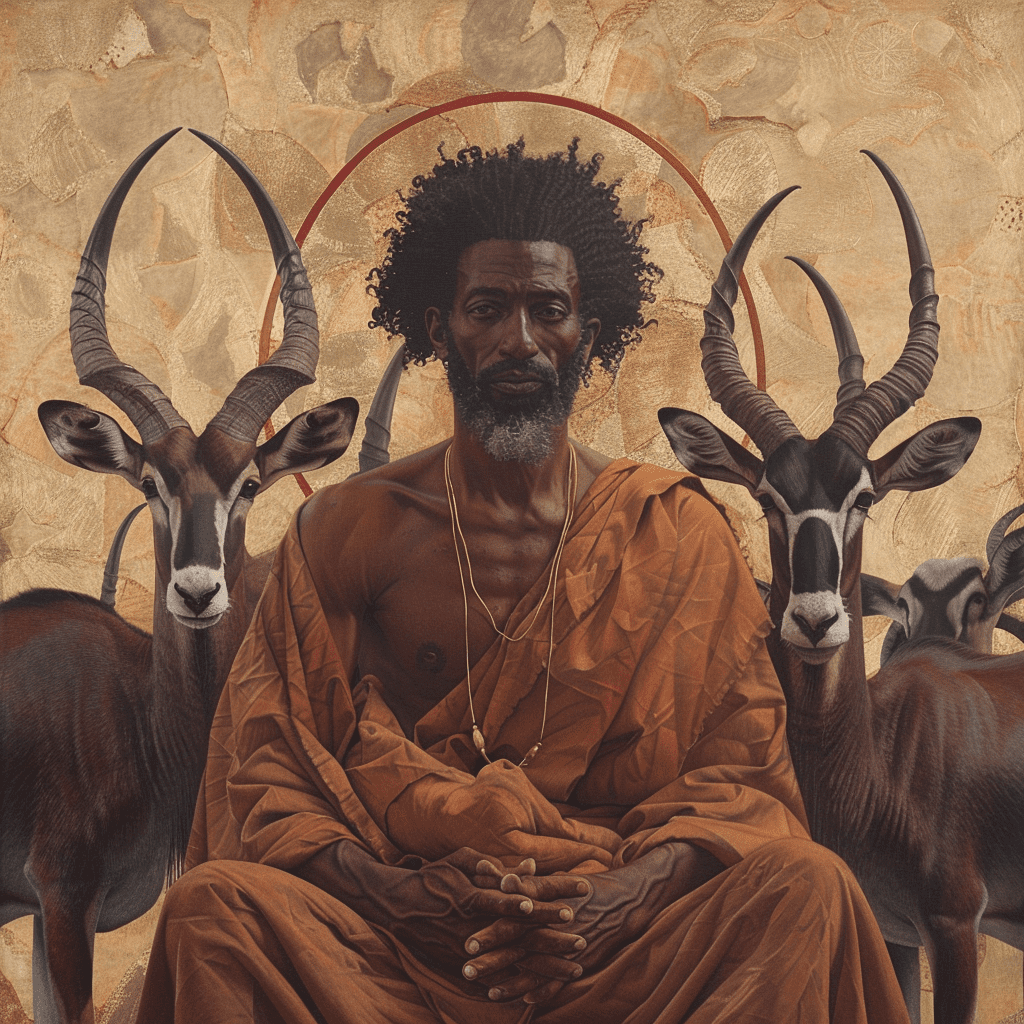

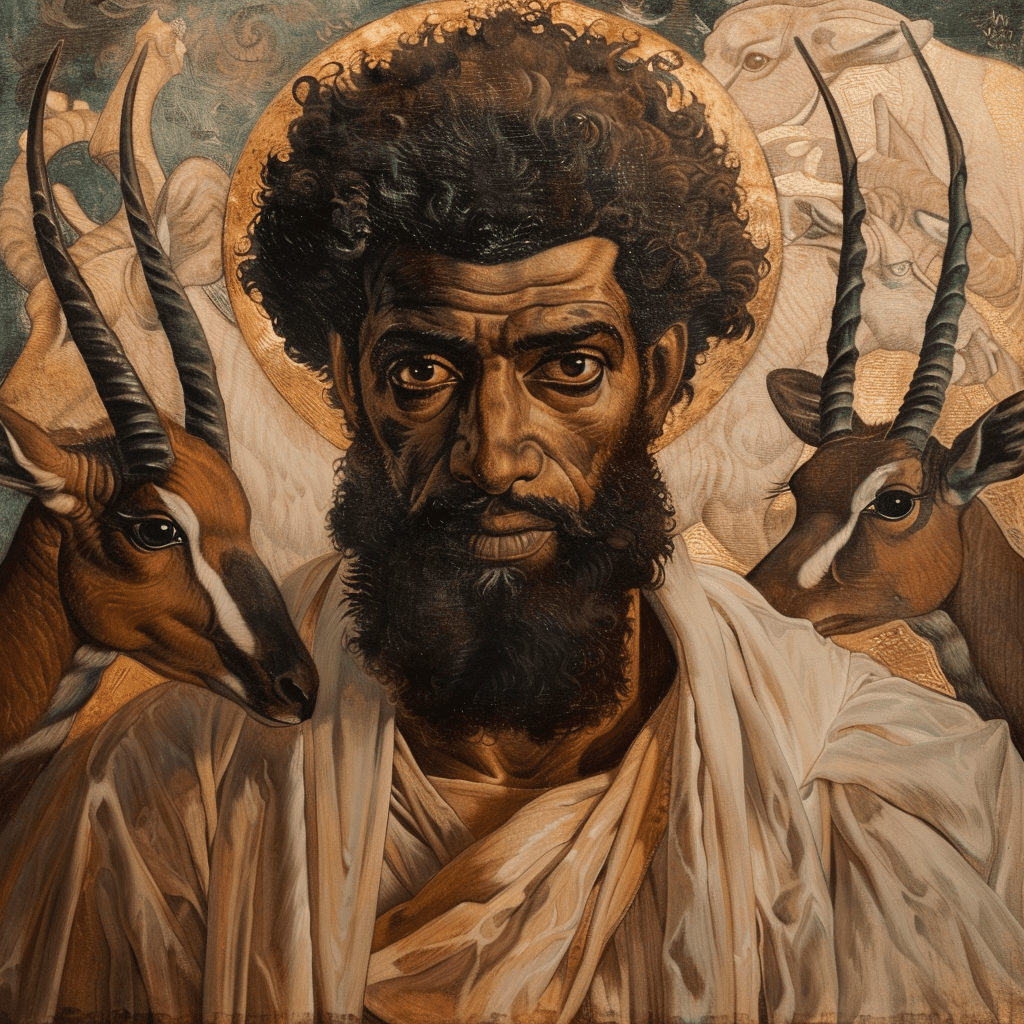

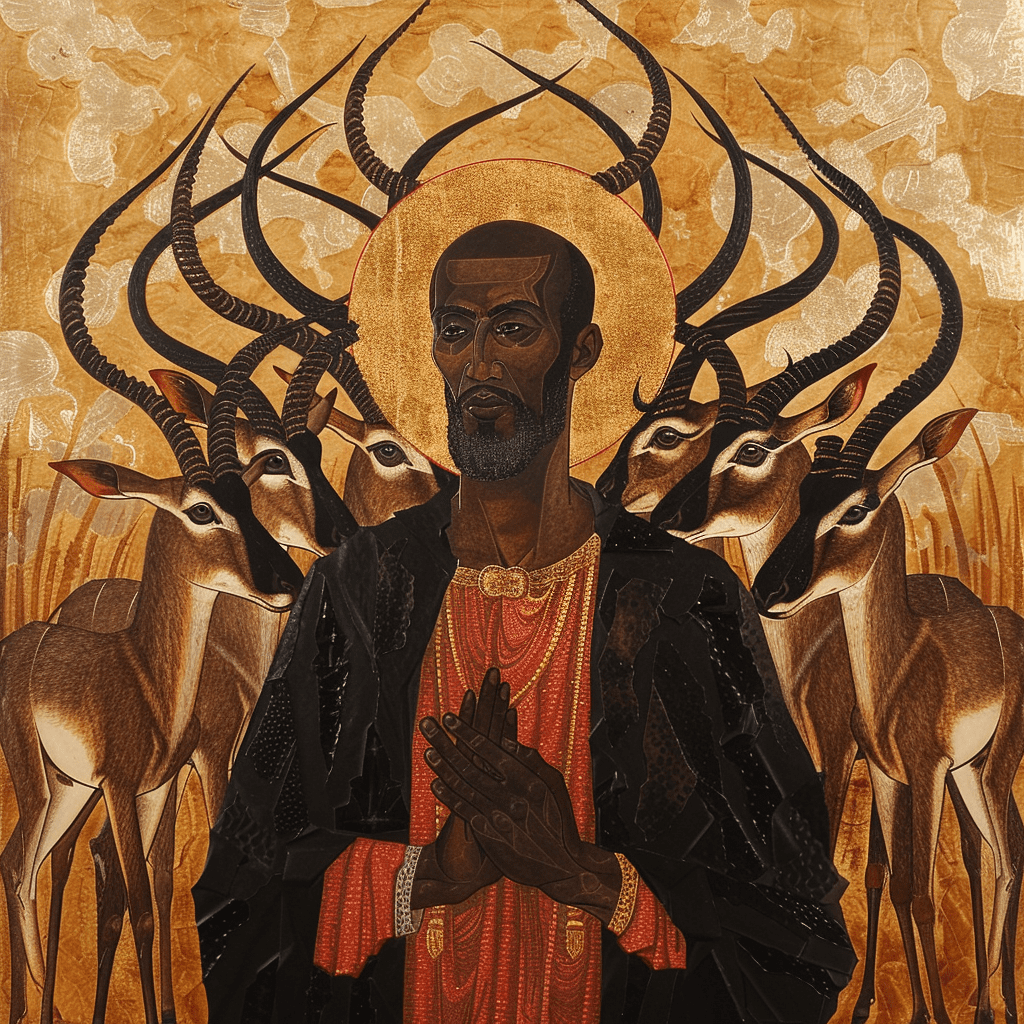

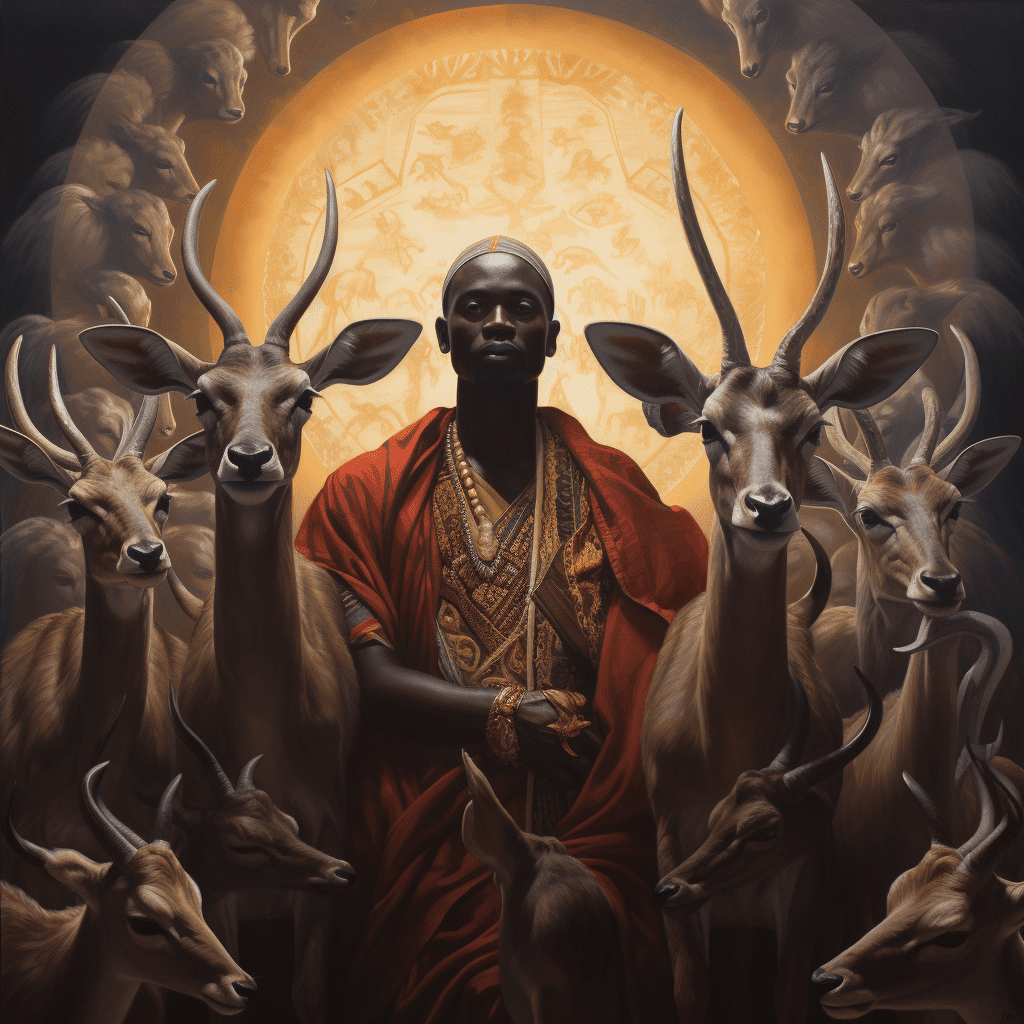

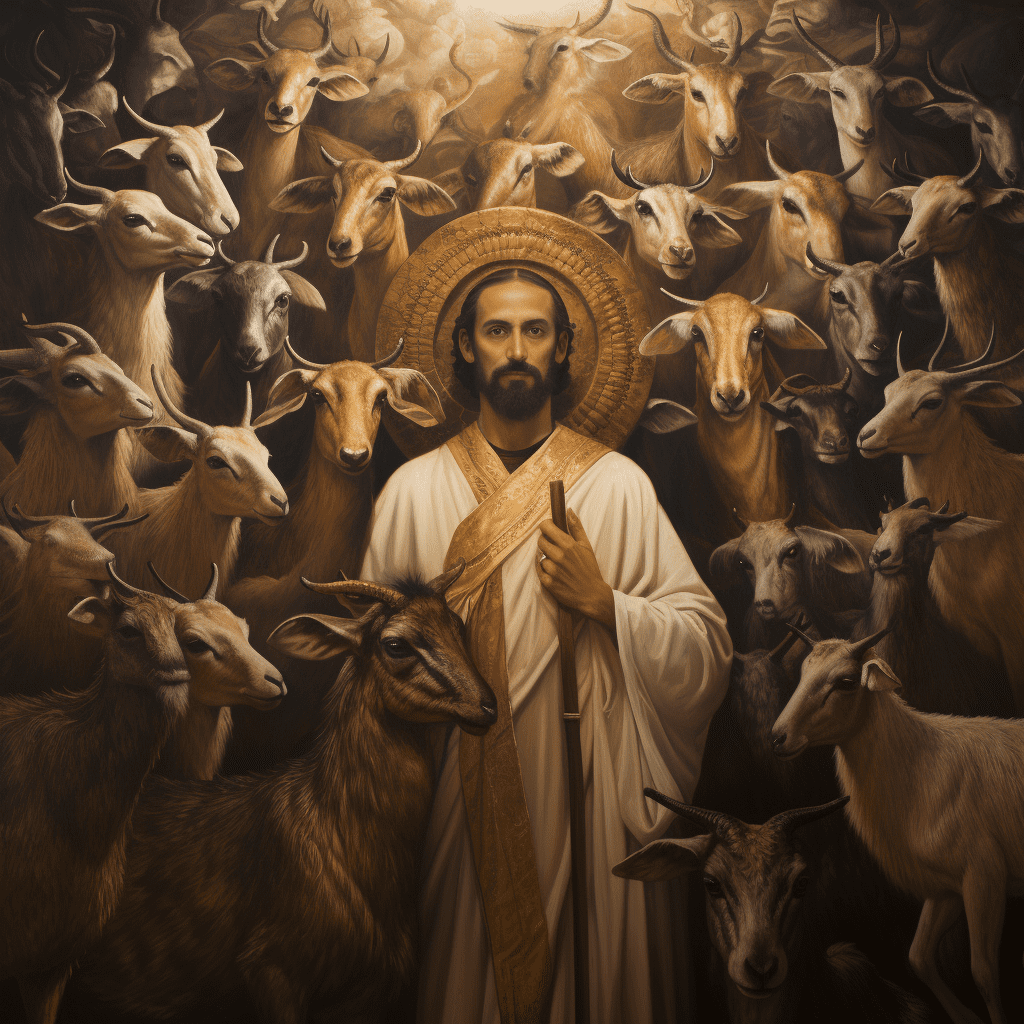

As you can now understand, I am in Midjourney’s AI generation room not to manifest my surface desires but to see this saint come to life. I worked with the prompts and edited the images as best I could. As the above images reveal, I was initially tempted to cast Aphou as dark-skinned, even Ethiopian. But because Theophilus’s question about Ethiopians was addressed to Aphou himself, it seems that the author of The Life of Apa Aphou did not understand the hero of the story to be especially dark skinned himself. As much as I might have wanted a black Aphou, I wanted to learn from, and not replicate, Google Gemini’s artificial diversity mistakes. I therefore had to guide Midjourney away from Aphou’s blackness, even though some of its initial results (such as the ones above and below) were particularly appealing.

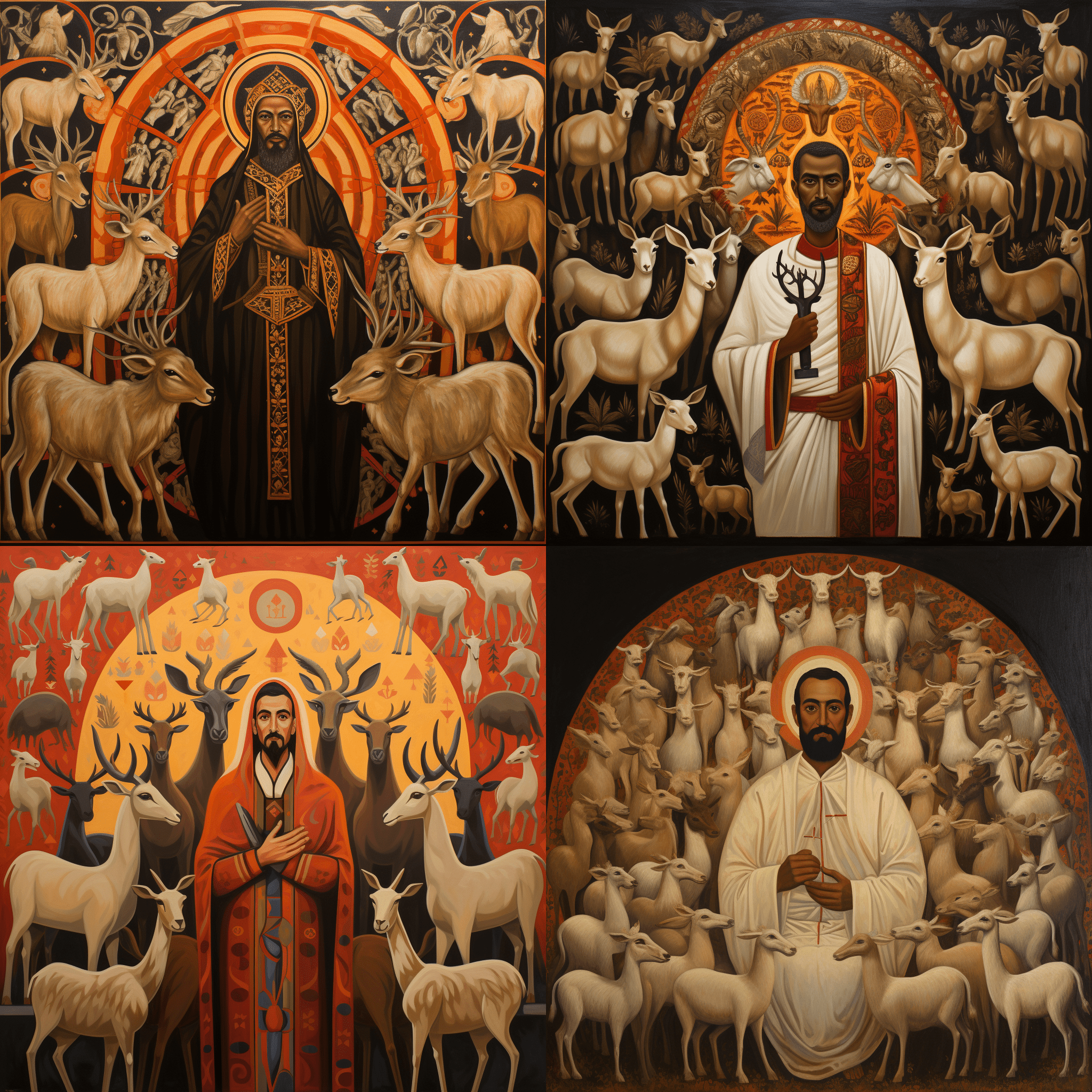

So I put the word “Coptic” into the prompt instead, hoping Midjourney might learn more from the Coptic iconographical tradition. These proved more probable. But the initial images of the Coptic Aphou made him look like an ecclesiastical Snoop Dogg about to slay a room full of criminals in a Tarantino film, and that did not sit right with me.

And so, after experimenting for some time, I found some particularly pleasing images (the ones below).

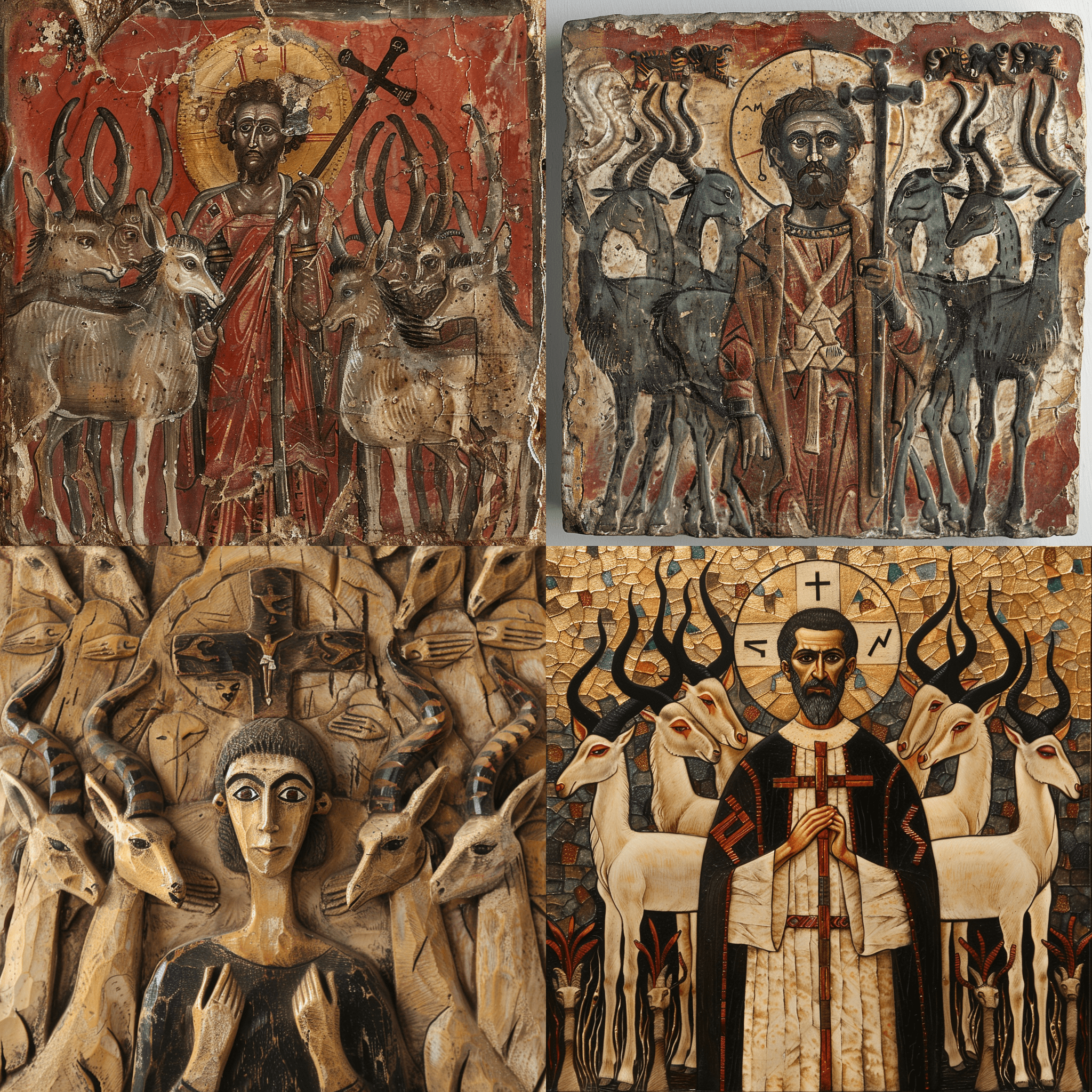

I then wondered if these images were too slick. Just as I was prepared to walk away from the experiment, preferring the ancient, worn surfaces of older icons, I decided to ask if Midjourney could achieve this ancient effect as well. Working with new prompts, I managed to generate images that looked like aged icons, as if they were lost paintings from the African monasteries examined in this column before.

The fact that these images of Aphou frequently sprouted wings might seem like a defect, but that is in fact how John the Baptist is frequently depicted in Byzantine art, which is something perhaps the Midjourney algorithms had picked up on. Still, seeing that wings on a human are traditionally reserved for John the Baptist, the divine messenger (Matthew 11:10, angelos in Greek), I steered away from this motif for Aphou. After correcting these and other errors, and editing the hands and head, I got an image that looked almost believable as an icon (to the right below). His feet almost resembled Egyptian hieroglyphs, illustrating Christian fulfillment of Africa’s ancient wisdom.

But these images did not sit right with me either. To “sacrifice the expression of the qualities of the material . . . however delightful [the] results in their first developments, [is] ultimately ruinous,” warned John Ruskin in The Stones of Venice. I therefore could not be satisfied with fakery, however appealing.

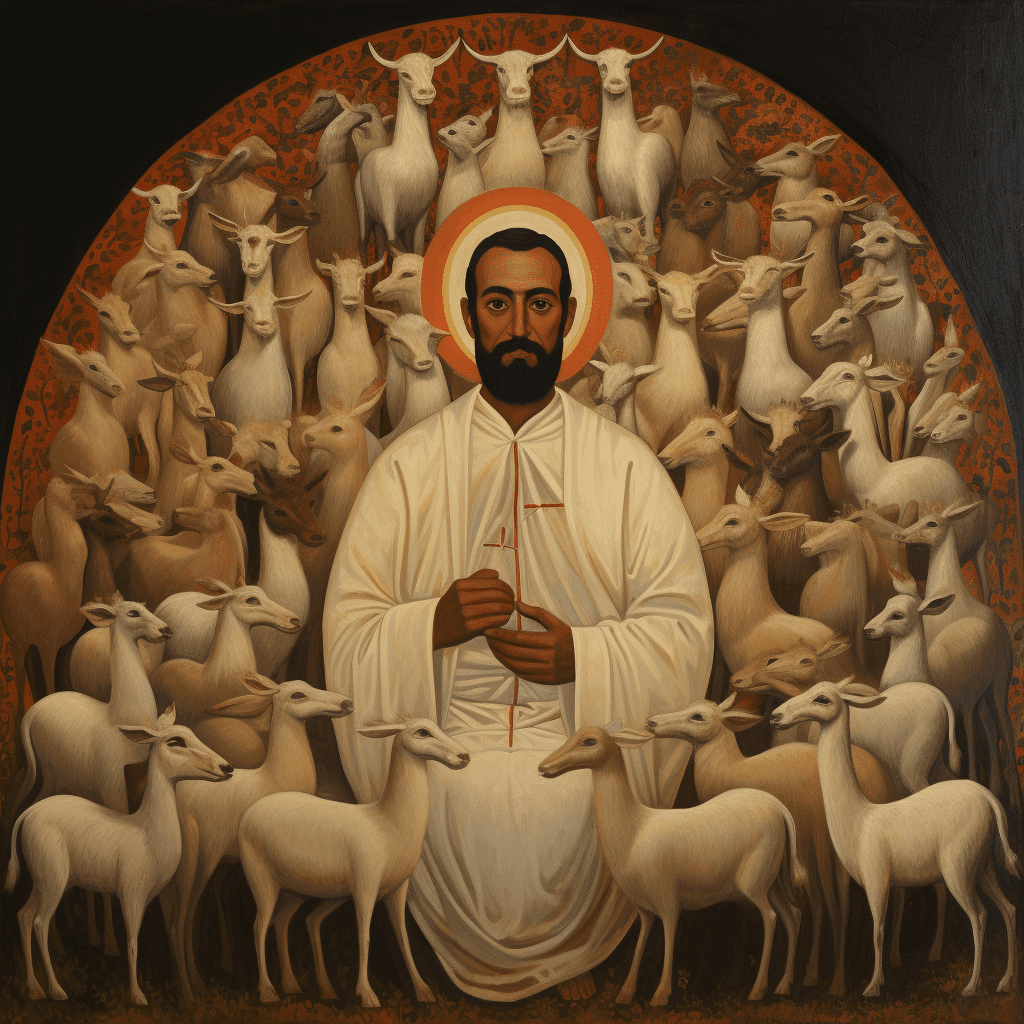

So, the end point of my experiment was that, slick or not, I went with the image below, attempting to be “true” to the screen-based medium of AI. I think it was the gentleness that drew me. This image was the opposite of the John Wick–style Aphou that looks like he’s about to assault me. It might be disputed that the antelopes are hornless in this image, indicating weakness. But Theophilus’s fragile ego might have been bruised if Aphou had taken the horn-locking, confrontational approach with an evidently egotistical bishop, so I kept the antelopes as they were.

The cream colour of Aphou’s halo was reflective of the colour of his wild companions. True, this Aphou was not gritty, but the brightness of his clothes emphasized his North African complexion and seemed to reflect his purity. If Sarah Coakley argued that three leaping rabbits can evoke the Trinity better than some literal depictions, could the three antelopes poised above Aphou evoke the Trinity as well? In this image, Aphou’s hands seem as if he is protecting a candle, reminding me of the great scene representing Christian lifelong fidelity in Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia. I even printed this image, laminated it, and hung it near an icon corner in my home. Could this AI-generated image help generate the same gentleness in me?

Perhaps all that was missing from the image I had created was what no AI platform can provide, no matter how much it advances: silence and prayer.

Given this possibility, had AI been redeemed just as Fra Angelico redeemed Renaissance developments? It could be disputed here that I did not reverently mix the colours myself or use hallowed materials such as gesso and egg tempera. Yet the great theologian Theodore the Studite (d. 826) argued that the point of Orthodox iconography is not the image itself, and certainly not the technique, but the prototype in heaven. We know that Aphou existed, and that his maligned Anthropomorphite tradition was in fact quite Christian even while it made room for mental images of Christ. Theodore said that icons must have a resemblance to the prototype, and seeing we don’t know what Aphou looked like, I suppose it’s possible that AI, with its algorithm-generated knowledge of Coptic iconography, put us in touch with him. Perhaps all that was missing from the image I had created was what no AI platform can provide, no matter how much it advances: silence and prayer.

Moreover, if we need a text to accompany this image, it is hard to do better than these words from Alexander Golitzin describing the Anthropomorphites, one of the finest stretches of academic prose I have read:

I might be tempted to call [Aphou’s tradition] the learning of the deep desert, but I think it is a good deal older than the monastic movement as we know that latter from its emergence in the fourth century. It is Christian, profoundly, but not quite the Christianity that we are used to, since its profundity draws so very deeply and confidently on the wealth of its Jewish roots. Some of those roots strike us, as they struck other and equally Christian contemporaries at the time, as outlandish and quite incredible, but they are very, very old. They antedate Paul and the Gospels, though I think that they are also the stuff out of which the Gospels and Paul’s theology are largely made, and they reach back into the foundations of Israel and, even before, into the ancient Near East. . . . It could and did accept Nicea-Constantinople, though only, I think, because the latter affirmed that the Lord Jesus is divine, and it has always known that, but it cared not a whit for the fine points of the debate.

Marrying serious scholarship with AI and Christian faith, I could see that the serenity on Aphou’s face was hard-won. The so-called Anthropomorphite wisdom was a wisdom that knew, as Golitzin says, that “patience . . . together with learning in the divine word, wisdom and holiness will always win out, in the end. Such was the perspective that could watch empires roll in and out, controversies over doctrine crash and roar, and not be moved.”

Still, the hours that it took me over multiple sessions to arrive at this image only depleted me. The platform imparted a weariness I had not experienced since teaching three classes in a row on Zoom. Generative AI, I learned, is anything but regenerative to the body or the soul. I paused to look at the images that were interspersed with my own on Midjourney’s platform. The prompts included “a stoned fox in a red jacket destroying the banking system with the help of cryptocurrencies.” The next patron asked for a “proud wild savage female wearing black leather grinning evilly and pointing a gun at you, speech bubble with the text ‘It’s over.’” Next, I was joined by someone, presumably a Christian, who wanted “the unfolded Bible, the ecstatic red sunset, the clouds reflected by the light of the ecstatic red sunset, and the pages of the unfolded Bible are gently reflected by the light.” At least my Aphou was better than that. Then came “Real estate (white guy) sitting at his laptop . . . looking at the screen with an excited look . . . saying ‘Property Management. I’m a Fan!’” Finally came a request for “a high-definition image of a modern urinal, presented in full view within a well-lit, clean bathroom setting.”

The latter request meant that each of my beloved Aphou icons was ensconced in a swirl of Marcel Duchamp–style urinals. I started wondering if the Aphou I had chosen looked too much like a Pixar character. I looked closer at some of the surrounding antelopes in my icon and noticed they were fit less for a holy icon than for a dime museum. Some antelope heads were merged together, and some only amounted to thwarted neck stumps. Still, the prospect of trying to fix these mistakes, training the software one more time, was repellant. I exited the platform, exhausted and—I began to fear—bamboozled, with my tarnished prize.

It felt like leaving a burning house.