L

Last summer, while driving from the Chicago suburbs to New York City, I stopped in Gary, Indiana, to fill up my tank of gas. A Rust Belt city once known for being the murder capital of the United States, Gary is mostly abandoned homes, boarded-up churches, and empty streets. For me, Gary was a brief stopover on a journey to a supposedly better place, a forgotten shell of its legacy as a booming steel town. Who would want to live here?

I thought of Gary, and this question, while reading Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America (Sentinel), from writer and photographer Chris Arnade. Like the former bond trader had done years ago, I was leaving my roots (mine, Ohio; his, rural Florida) to move to New York City and join the echelon of successful Americans surrounded by top private schools, co-ops, and all the culinary and creative pleasures money could buy. Or, in Arnade’s terms, I was looking for my seat in the “front row,” the destination of those privileged enough to walk the narrow path of educational success in America. I had made it, or so I was told.

So it’s striking that Gary, Indiana, is one of the dozens of towns that Arnade leaves New York City for. In 2011, Arnade was growing tired of his lucrative but soulless job on Wall Street. During long walks after work, he began visiting Hunts Point, a South Bronx neighbourhood known to outsiders for its drugs and prostitution. He started talking to people who lived there: not non-profit leaders, politicians, or other “experts,” but to people like Takeesha, a heroin addict who had been working the streets since age twelve. When Arnade asks Takeesha how she wants to be described, she answers without missing a beat: “As who I am. A prostitute, a mother of six, and a child of God.”

God shows up a lot in Dignity: in small Pentecostal and evangelical churches, yes, but also in the local McDonald’s and Walmart parking lot—anywhere that people barred from the front row rest, reminisce, laugh, fight, read their Bibles, visit friends, and simply survive. Hunts Point, and other US neighbourhoods like it, “wasn’t what I was told I would find,” writes Arnade. “It was welcoming, warm, and beautiful, not empty, dangerous, or ugly.” Over three years, Arnade traveled 150,000 miles cross-country to visit places he was told to avoid: Portsmouth, Ohio, Milwaukee’s North Side, Bakersfield, California, Prestonsburg, Kentucky, Selma, Alabama, and many others. What emerged from his travels is an incisive, often profound account of life in “the back row.” He found that the people who are ridiculed, scolded, or simply forgotten embody virtues that the technocratic elite can’t seem to recognize, let alone measure.

People in the back row, of course, have received much media attention in the era of Trump. Heading into the 2020 election, Democratic candidates are urged to understand the grievances of the white working class if they want to run against the current president. But Dignity is not a book about Trump. For one, Arnade began working on it back in 2011. And he intentionally visited cities, which, taken together, represent the diversity of the country. While much of the book is spent detailing the frustrations of white, rural voters, a majority of Arnade’s interview subjects are African American, and national politics typically doesn’t come up.

In this way, Dignity avoids tired tropes about poor rural Americans, in large part because Arnade chooses proximity over punditry. Talking heads pronounce from afar, but Arnade draws close. He seems to be motivated by a genuine search for understanding rather than a preconceived narrative that will grab headlines. Some of his conversations lead to real friendships. When Millie, an addict from Hunts Point, dies without paperwork or identification, her body is sent to Hart Island, put in a plywood box alongside a million other bodies a mile off the eastern shore of the Bronx. When Arnade learns of her death, he helps get her body exhumed and gives her a proper burial.

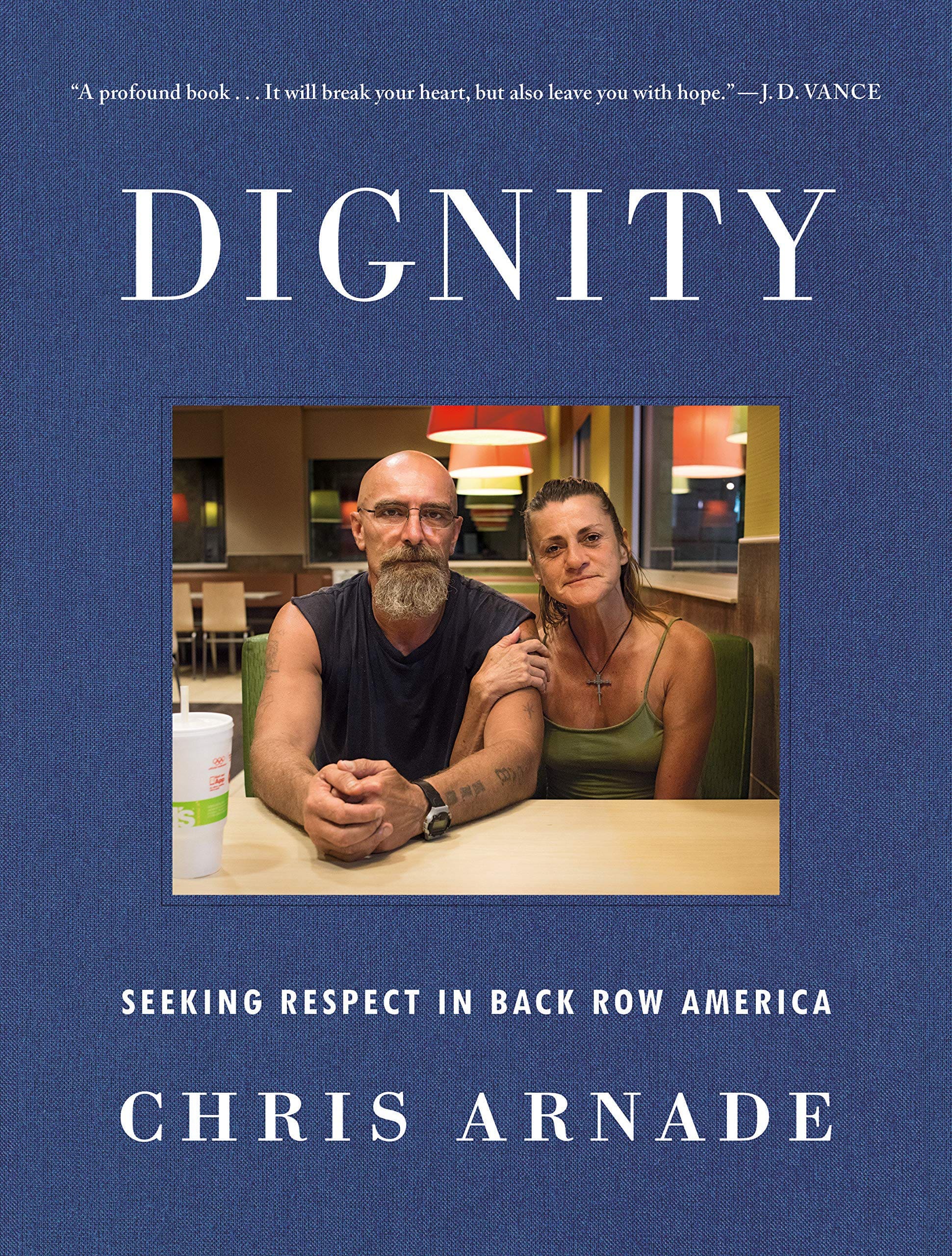

Much of what Arnade finds in the back row is predictable in its heartbreak. To a person, his subjects are either currently on drugs, recovering from them, or close to someone who has died from abusing them. The book’s striking colour photos, with closeups of needles and veins, testify to the ravages of addiction. For many, drug addiction is about choosing a slow death to escape the hellish conditions of life. Bernice, a thirty-six-year-old sex worker in Hunts Point, tells Arnade she has been selling herself for drugs since age nineteen, a victim of childhood trauma. She says matter-of-factly, “I am out here trying to kill myself. I want to get a gun and do it faster, but I am too scared to blow my head off.” In the back row, drugs numb not only personal pain but also social pain—the pain of being rejected in most circles. They provide community for people who can’t find it anywhere else. “A drug trap, or a drug corner, is a place to hang and fit in,” Arnade writes. “A place that welcomes you regardless of your past.”

The need to belong is also behind the rise of “racial identity,” Arnade’s term for white nationalism. According to Arnade, taking pride in racial identity appeals to white Americans in the back row because “it offers a community with a long (and ugly) historical legacy, boosting its sense of importance. It also offers plenty of scapegoats to punch down at.” For example, in Lewiston, Maine, economic decline coupled with an influx of Somali refugees who receive certain benefits (Section 8 housing, free legal help) leads to overt racism and resentment, that minorities are getting “handouts.”Arnade notes that Trump exploited this resentment in 2016, giving aggrieved white Americans a shroud of respectability. But white racial identity has done practically little to change back-row Americans’ economic prospects. Like drugs, racial identity numbs the deeper pain of social humiliation without healing it.

But Arnade leaves the harshest words for people like himself. The “front row” has its own racism: the kind that proudly advocates for justice for minorities while perpetuating an educational system and worldview that excludes and ridicules them. The journey to the front row in America “ranks people by how much you learn and earn, and it is rigged against the back row, and minorities disproportionally start and confined there,” notes Arnade. There are no pats on the back here for urban progressives who hold the right political views but largely remain in exclusive neighbourhoods, workplaces, and social circles, deaf to their neighbours’ cries a subway ride away.

Dignity exposes the vacuum of meaning in the front row while honouring the richness of meaning in the back. There, home is central, because it is the backdrop against which the “connections, networks, friends, family, congregation,” and all the other things that constitute a human life unfold. Some interview subjects want to leave their hometown but can’t; for many, a responsibility to care for family overrides personal preference. When Arnade asks Frank, a lifelong resident of Amarillo, Texas, if he likes it there, Frank answers, “Hell, I was born here. Have to like it. It is home.” Such an outlook challenges the myth that the best life is necessarily found by leaving home, that success means being able and willing to move at the hint of a new career opportunity. Physical mobility ensures economic mobility. But in a deeper sense, to be able to go anywhere is to belong nowhere—not in any way that accounts for family, history, and the potency of memory.

And here is Arnade’s distinctive contribution: He gives ample attention to the role of faith. Arnade grew up in the Catholic Church but left it as soon as he moved away from home. Nonetheless, he finds himself in churches for the same reason he goes to McDonald’s: “because the people I wanted to learn from spent their time there.” Churches, perhaps more than any other institution, provide people in the back row with inherent value, belonging, and hope. For some, they also provide a pathway out of addiction. But even for those still ensnared in drugs, the reality of God and of evil are obvious; after all, how else does one name the large, unseen forces that rip apart families, devastate local economies, and leave people desperate for the relief of death? Witnessing the power of prayer and worship among his subjects, Arnade grapples with the limitations of the scientism and data worship found in the front row. “My biases, my years steeped in rationality and privilege, was limiting a deeper understanding. . . . Getting there requires a level of intellectual humility that I am not sure I have.”

Dignity is not a solutions book, nor does it try to be. Arnade doesn’t provide a plan for “lifting the back row out of poverty” or helping the front row grapple with their own insidious forms of exclusion. Instead, it demonstrates by way of example the transformative power of proximity. While reading Dignity, especially while spending time with the stunning photos throughout, I thought of the line from Victor Hugo that “to love another person is to see the face of God.” Except that it came to me as an equally lovely inversion: To see another person is to love the face of God. More than policy proposals or legislation, we begin to heal by really seeing each other. This book teaches us to see a bit clearer.