I

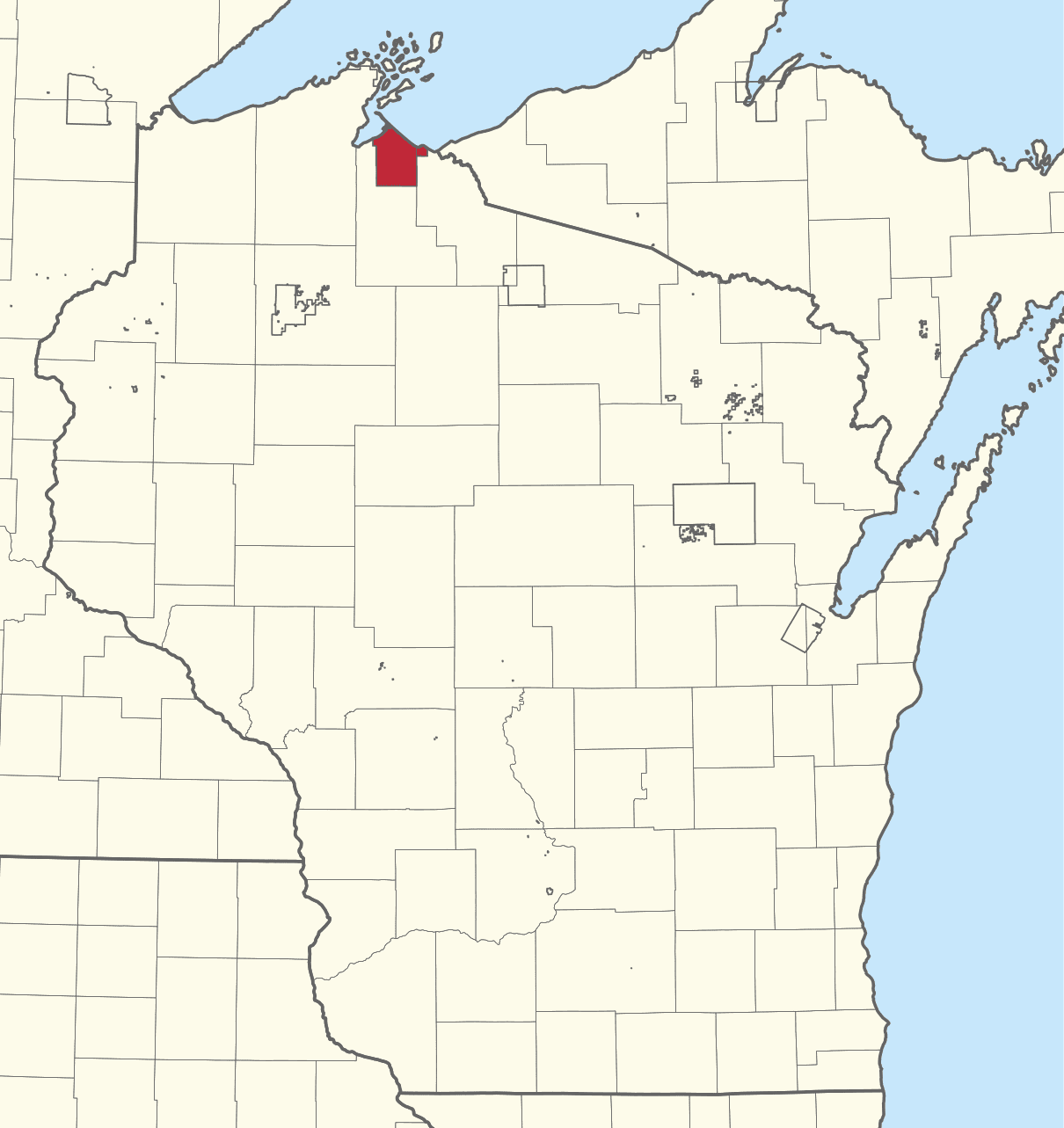

It is midnight at the Bad River reservation in northern Wisconsin, and my career as a teacher may have come to an end. I put on worry like a comfortable pair of jeans. Little about the current situation feels right. The connection was too tenuous, the plans too hastily enacted, the precious lives of college students too casually hazarded under the banner of “experiential learning.” We arrived only a few hours ago, the first outside visitors to the reservation since the pandemic, and our van and canoe trailer were met with puzzled stares. Our host took us to the powwow grounds to set up camp but then had to leave to conduct a funeral. While we set up our tents, cars began to drive by, clearly aiming to get a look at our group. “What are you doing?” came a shout from one vehicle. “Camping,” I cheerily yelled back. “On the powwow grounds?” came the reply, followed by screeching wheels.

When one group of men parked nearby, I wanted to go greet them, but a student in our group, fearing for my safety, stopped me. “Don’t be a hero, Dr. Milliner.” The young men walked solemnly into the woods, where they raised their arms in what I assumed was an Indigenous ceremony hitherto unknown to me. When I pointed this strange ritual out to a student, she replied politely, “I think they’re fishing” (which they were).

Soon our host arrived. His name is Micheal John Reszler, a former Franciscan novitiate who is now a Methodist minister but is equally conversant with traditional Ojibwe customs. He put us at ease with disarming humour, assuring us that those who had driven by were just curious and that all would be well. In any case, he had now explained to everyone who we were. He stayed with us for hours, explaining his ministry to the Christian and non-Christian members of the tribe. We exchanged gifts. The sunset gave way to firelight. The ways he fuses his Ojibwe and Christian identities, he told us, tend to make both Ojibwe and Christians nervous (including, I concluded after eyeing our gathering, some of us).

Still, it’s midnight now, I’m in my tent, and though nothing has happened, I’m thinking this could be it.

My fear isn’t entirely irrational. As we entered Bad River today, the Little Finland gift shop and Faith Family Freedom billboards gave way to signs about missing and murdered Indigenous women and the Native Youth Crisis Hotline. I suppose my fear should give me more sympathy for my settler ancestors, who harboured suspicions about the original inhabitants of this land based on reports, amplified by hearsay, of violent frontier crimes. Even so, my own worries have a unique twenty-first-century flavouring. I imagine, after a theft or worse transpires, how some back home will blame me for wandering from the realms of trusted evangelical Christianity into “pagan” domain, while others will accuse us of appropriation for daring to entertain Indigenous culture without being native ourselves. Who will reconcile fractured evangelicalism? I will! Its right and left flanks will be momentarily unified in complete agreement that my ill-fated attempt to bring Wheaton College students to Bad River was a very bad idea.

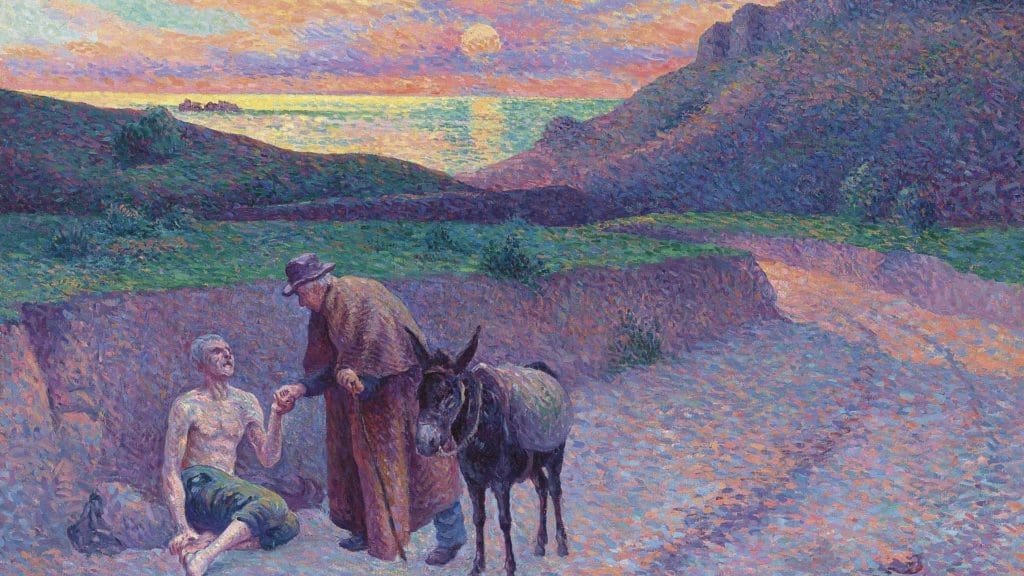

But nothing went wrong. My worry was mercifully euthanized by sleep, and when we woke up the next morning, several of us reported fantastic and rejuvenating dreams. Our host showed up with donuts and coffee to continue the casual and disarming conversation. Then he drove us to a special prayer spot used by his ancestors. He set us free for silent prayer for “about half an hour” (Revelation 8:1), after which we joined together again. Sage, tobacco, cedar, and sweetgrass, burning in an abalone shell, were transformed into smoke and wafted toward each of us with an eagle feather, a ceremony known as smudging. “May my prayer be set before you like incense” (Psalm 141:2). All of this was to launch us, in the name of Jesus Christ, on an Ignatian prayer retreat that we had come for. If Ignatian spirituality was the first form of Christianity to make contact in this region more than three centuries ago, the least we could do—atoning for Christian disunity—was to honour this Catholic tradition as Protestants. And if those early Christian missionaries, even the Jesuits, had insufficiently attended to Christ’s presence in the Indigenous cultures they encountered, there was no reason we had to make the same mistake today.

Sage, tobacco, cedar, and sweetgrass, burning in an abalone shell, were transformed into smoke and wafted toward each of us with an eagle feather, a ceremony known as smudging. “May my prayer be set before you like incense.”

Our next stop was Mooningkanewaaning, a.k.a. Madeline Island on Lake Superior. It is fitting that this island is scattered among the Apostle Islands, for Madeline derives from the name Mary Magdalene, whom the early church celebrated as “equal to the apostles.” But the island is also known as the Ojibwe Jerusalem, and we are her pilgrims. Wheaton College has a Wheaton in the Holy Lands program and even a Jerusalem semester, but this course takes students to the other Jerusalem. If the original Jerusalem is the end point of wandering through the wilderness, Madeline Island is no different. The Ojibwe once dwelt on the eastern coast of the continent, but a prophecy warned them of coming settlement, sending them on a migration westward to a place where the food grows on water. For the Israelites this food was manna, and for the Ojibwe it was wild rice, which was harvested on Madeline Island, where the Ojibwe arrived around the late fourteenth century. It is from here that their population grew and then branched out to the mainland, frequently in competition with the Sioux and in relatively harmonious concord with the trading networks of the French.

But the prophecy was correct, and the sweep of settlement ultimately reached Madeline Island as well. The land of the Ojibwe, including their Jerusalem, was sold in 1842 at the treaty of La Pointe. (Suspiciously enough, the majority of the payment of the treaty went to those associated with John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company.) The Ojibwe seem to have been promised they would not be removed if they “behaved.” But within six years, President Zachary Taylor signed the removal order. Ostensibly, this was to protect Ojibwe from “injurious contact” with the whites.

To facilitate removal, federal officers insisted the 1850 annuity payments no longer be delivered on Madeline Island itself. Instead, the Ojibwe were forced to travel to Sandy Lake, Minnesota. Of the fifty-five hundred that made the trip, nearly five hundred died as a result of the hardships of the journey. In an 1851 letter, Kechewaishke (Chief Buffalo, d. 1855) wrote, “Our women and children do indeed cry, our Father, on account of their suffering from cold and hunger. . . . We wish to . . . be permitted to remain here where we were promised we might live, as long as we were not in the way of the Whites.”

But Chief Buffalo did more than plead. At the age of ninety-three, he travelled to Washington, DC, by canoe, foot, and rail to defend his people. There he explained to President Millard Fillmore his assumption that the 1842 treaty was for pine and minerals, not a cession of the land itself. Chief Buffalo was heard, and four reservations were created in Wisconsin: Lac Courte Oreilles, Lac du Flambeau, Red Cliff, and Bad River, where we had just spent the night. This puts my initial fear into perspective. I sympathize with those who drove past our visiting group suspiciously, as if to ask, “What do they want this time?”

It is my second year at Bad River now, and I’m much more relaxed. Our same host meets me and a fresh group of students, this time showing us even more hospitality than before. We have not come to build homes, fix things, or run a youth camp (laudable as such activities may be) but again just to learn. This time a few more Indigenous terms are shared, a few more ceremonies permitted. I tell our host that while we were unable to locate Chief Buffalo’s grave on Madeline Island last year, the fact that Chief Buffalo was of the crane clan was a suitable enough connection, because when I arrived at our campsite, a solitary crane had squawked at me and flew on. Our host smiles. “Looks like he found you first.” Before my typical “It was just a crane” suspicion can settle in, I learn that our host is related to Chief Buffalo himself.

As we gather around the campfire again, I throw out a few questions to jump-start the conversation. I have read about contested accounts of Chief Buffalo’s conversion to Christianity, some saying it was disingenuous, others that it was real. Our host disputes the question itself, insisting that it assumes a clear line between Ojibwe and Christian identity that makes little sense in practice. Chief Buffalo did not “convert” because he did not see his traditional tribal and Christian pathways as necessarily distinct. Any allegiance to Christianity expressed on his deathbed was a further manifestation of what had already long been the case. As our host speaks, I feel the distinction between secular and sacred, birthright of the Western psyche, a bit further erased. I feel my trust in airtight theological categories replaced with a deeper trust in the ever-and-always-present Christ. It strikes me that in my generation’s search for forms of “non-dual Christianity,” we have overlooked Indigenous Christian wisdom again, just as my ancestors did. Like fathers, like sons. But there is an American advaita (“not-two” in Sanskrit) too, presided over by an Indigenous Christ.

As our host speaks, I feel the distinction between secular and sacred, birthright of the Western psyche, a bit further erased.

We sleep on the powwow grounds again. In the morning we awake and, unprompted by me, students report more beautiful dreams. Our host takes us again to the same special prayer spot. This time I invite students to ride with Micheal John and me. We learn that concern about (or, in academic fashion, for) “animism” is simply a non-issue for the Ojibwe, for “the Great Spirit pervades all things (Psalm 104:30), things that can have their own spirits and wills as well.” Confirming this insight, my co-leader later points out how Robin Wall Kimmerer asks in Braiding Sweetgrass, “By what linguistic confluence do Yahweh of the Old Testament and yawe [the word “to be” in Potawatomi] both fall from the mouth of the reverent?” Even so, lest we think Micheal John naive about the reality of malevolent spirits, he shares with us about the fentanyl overdoses that afflict his community (and ours), alongside a story about what amounts to an exorcism.

Again, we spend time in silence with Micheal John to launch our retreat. Then we pray, we are smudged (“and the smoke of the incense, with the prayers of the saints, rose before God” [Revelation 8:4]), and we sing. Migwech Gitchi Manitou, aweni manitou, Anishinaabe. “Thank you, Great Spirit, and the Spirit of the people.” By concluding our prayer with the name of Jesus, it becomes a trinitarian address. I ask if we have permission to sing this song as our retreat continues, and, of course, the song is granted, as is—to our collective astonishment—the turtle shell, deer hide, and otter-fur rattle that kept rhythm while we sang. An immature bald eagle crests the skyline as we conclude our prayers.

The canoeing, the portages, the visits to sacred pictographs, the cold plunges into Lake Superior, our finally locating Chief Buffalo’s hidden grave—all are ahead of us. But this ceremony is why we have come. I think that my career as a teacher might as well be over, as I can’t imagine any experience, including in the original Jerusalem, more saturated with meaning than this.

Still, whether we return to Bad River again, our host reminds us, remains in the Creator’s hands.

This piece was written in collaboration with, and with the permission of, the community of Bad River Reservation.