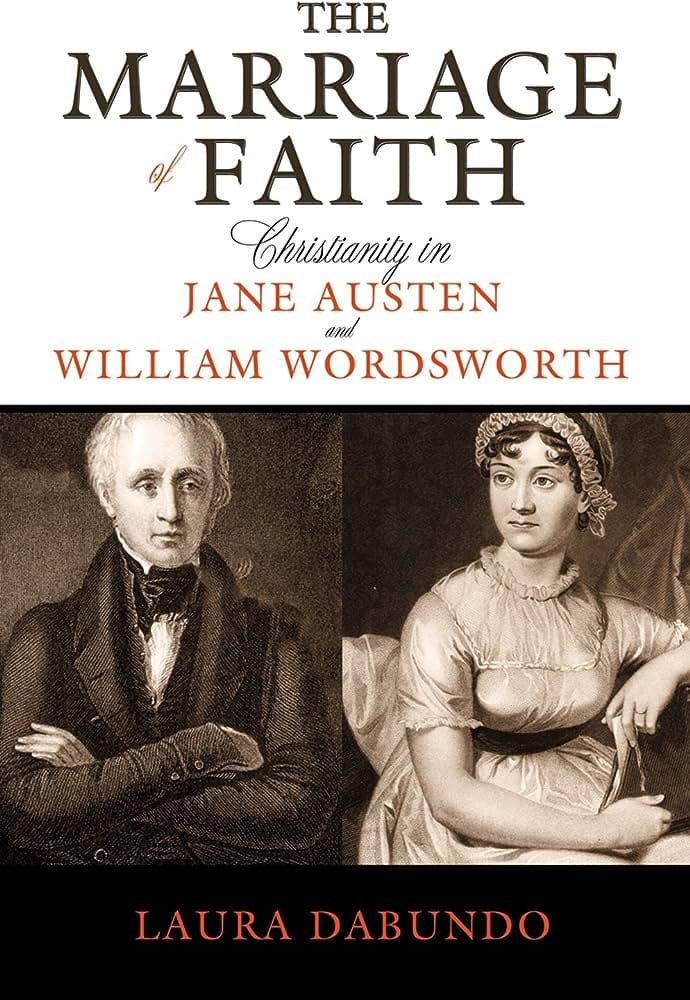

A new book on Jane Austen and William Wordsworth provides an opportunity to test Peter Leithart’s thesis in his recent Comment editorial: that Scripture’s most lasting effect on the city of man is creative. The Word of God is living and active in the world through the work of writers, artists, and musicians who are moulded by Scripture. Austen, Leithart writes, “did not discover from an inductive Bible study that God wanted her to write novels a certain way. Her writing is ‘biblical’ because the Bible pumped through her veins. She couldn’t have written in any other way.” In The Marriage of Faith: Christianity in Jane Austen and William Wordsworth, Laura Dabundo seeks to recover what contemporary readers of Austen and Wordsworth would have recognized, namely, the constant pitch and steady beat of Christian faith in their prose and poetry. Austen and Wordsworth are not religious writers in any deliberately programmatic or intentionally apologetic sense, Dabundo argues, yet they are the more powerfully religious for their profound Christian commitment to the biblical vision of social harmony. Not only is such an argument interesting in its own right, it can also serve as a test of Leithart’s thesis about the perduring influence of Scripture in the city of man.

The case for Austen’s and Wordsworth’s Christian vision, as the title of Dabundo’s book suggests, rests on their vision for human flourishing in community. Dabundo argues that the trajectories in Austen’s fiction and the motifs in Wordsworth’s poetry are propelled by marriage as the ideal expression of society: “The marriage of true minds, then, captures the intrinsic and intimate community that Wordsworth and Austen espouse, the vision of love and compassion, faith and trust, the earthly epitome of the kingdom of heaven.” In the subsequent chapters of this short book, Dabundo offers a close reading of Wordsworth and Austen to demonstrate the biblical pattern of sin, redemption, and consummation in their work. The basso continuo of their writing, Dabundo argues, is “their visions of a redeemed world, transformed, united, and faithful, from marriage to community to world to the coming and yet always-present kingdom of God.”

The evidence for Dabundo’s argument is strong for both Wordsworth and Austen. Dabundo presents a Wordsworth who is under-represented in anthologies of Romantic literature, a Wordsworth who is committed to expressing in verse a Christian vision for being-in-the-world. Reading well-known texts by Wordsworth, such as the autobiographical epic, The Prelude (1850), in tandem with his lesser-known texts, such as The Excursion (1814) and Ecclesiastical Sonnets (1822), Dabundo shows the Anglican Christianity that runs throughout Wordsworth. Rather than a series of abrupt discontinuities, the development of Wordsworth the young radical to Wordsworth the elderly poet laureate is one inflecting the biblical motifs of marriage and community in different ways. Critics tend to repeat the often-unexamined dictum that the later Wordsworth is conventional, orthodox, and boring compared to the Wordsworth of “Tintern Abbey” and Lyrical Ballads. Dabundo corrects this misconception by showing the abiding presence of biblical ethics and aesthetics throughout Wordsworth’s long career. Not only does Dabundo demonstrate that the clergy in Wordsworth function in the positive symbolic role of the reconciler or mediator, she suggests that Wordsworth’s revolutionary politics are predicated on a vision of Christian community.

When Dabundo turns to Austen, we are on more familiar ground. On the evidence of her own prayers, letters, and the testimony of her siblings—two of whom became Anglican priests—Austen actively participated in the rites of the Church of England. In Leithart’s words, “She grew up in the home of an Anglican pastor, where she heard Scripture read, performed daily prayers, participated in the weekly liturgy from the Bible-saturated Book of Common Prayer.” The fact of Austen’s Christian faith is not generally disputed. What is of interest is how Scripture’s influence manifests itself in her novels. Leland Ryken, in his contribution to A Complete Literary Guide to the Bible, suggests that “One of the most important ways in which the Bible has influenced storytellers is in the development of characters and plots.” Dabundo provides persuasive examples of this in Austen, even in surprising ways. For instance, Dabundo notes that all of Austen’s protagonists experience some form of fall—a chastening experience that brings self-awareness, humility, and eventual restoration. Thus, the central pattern of the “grand narrative” in the history of salvation, which is echoed repeatedly in the “micro narratives” of the Bible (such as in the episodes recorded in Judges), is also the pattern of Austen’s characters and plots. This makes for neither escapist fiction nor superficial romantic conversion narrative, but a realism that is embedded in the deep structure of Scripture and of history. The affective experience of reading an Austen novel like Pride and Prejudice—whether in 1813 or in 2013—is one of inhabiting the fall-to-redemption pattern through character and plot.

Dabundo relates the biblical patterns of character and plot to Austen’s commitment to the community of the Church in England . Critics of Austen are too quick to make money and matrimony the goal of her novels, while Dabundo argues that a female community of sisters and sister-like friends is an important dimension of Austen’s vision for community. Matrimony is a metonym for relationship, community, and social harmony more generally, as it is in Scripture itself, “signifying the consecrated relationship and community from which, in effect, congeries of concentric circles radiate outward.” More than merely a signifier of status and the sign of a conventional comic ending, matrimony in Austen gestures at something beyond the material, social function of marriage.

Both Wordsworth’s political vision of England as Christian community and Austen’s vision of social harmony are illustrations of Peter Leithart’s thesis regarding the Bible’s influence in the city of man: “Scripture’s most lasting effects on civilization are creative rather than evaluative.” This realization is hugely encouraging for Christian artists, musicians, and writers seeking to speak prophetically into the city of man today. Biblically informed art is not only that which uses the Bible as a source for didactic purposes but especially that which allows the influence of Scripture to work its infusive, pervasive, deep magical effect. Scripture is the solid rock upon which the wise artist builds house with gold, silver, and costly stones. The shapes and structures of Scripture, its plots and protagonists, its forms and figures, and its rhymes and rhythms, are the warp and woof Christian art.

Leithart’s observation should also encourage readers who recognize the salutary cultural force that biblically-resonant literature continues to exert in the present. Because writers such as Austen and Wordsworth, Dickens and Dickinson, Greene and Eliot, Updike and Levertov, are fundamentally biblical in their vision for the world, their works still speak to our cultural moment. Indeed, the two hundred years of world-altering history that separate us from Austen and Wordsworth have bequeathed to us a significantly different set of preoccupations. And yet our times are not so radically different from those of Austen and Wordsworth, when Europe was increasingly marked by philosophical skepticism, environmental pollution, political and economic changes, pragmatism, and social instability. The antidote, then and now, is a biblically-informed vision of community, a way of imagining the kingdom with poetic and kinaesthetic longing that Jamie Smith describes in the second volume of his Cultural Liturgies project.

Literature characterized by the dominant traits of Scriptural DNA, like the poetry and prose of Wordsworth and Austen, embodies the case for a biblical worldview creatively. Like the operation of the “Deeper Magic” in Narnia, the influence of Scripture is more felt than comprehended in literature that breathes the biblical atmosphere. Canonical and marginal authors whose works transpose into narrative, poetic, and dramatic forms the biblical truths that are propositionally articulated by theology, philosophy, and political science extend the creative influence of Scripture through their characters, plots, imagery, and poetic forms. Northrop Frye had two goals in view when he wrote The Great Code: The Bible as Literature: to demonstrate the impact of the Bible on the creative imagination and to convince readers that the Bible should be taught as literature in public schools. David Lyle Jeffrey and Greg Maillet in Christianity and Literature: Philosophical Foundations and Critical Practice (2011) identify ten characteristics of “the Bible as a foundational literary text with massive influence on literature in the English-speaking world” (95). But Frye makes an even more comprehensive claim for the Bible than Jeffrey and Maillet. In The Educated Imagination (1963, 1983), as in The Great Code, Frye claims that the Bible is a necessary corrective to the narcissistic and materialist social mythologies of the West. Biblically grounded fiction and poetry are like Christ’s parables in that they make real in character and plot, image and form, what the coming kingdom looks, sounds, and feels like. Perhaps the real reason for the immense popularity of Pride and Prejudice, The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, and Les Miserables is the biblical vision at the core of these texts, a vision that not even Hollywood can ignore.