This fall, a few of the Comment staff had a chance to enjoy an evening with Marilyn Chandler McEntyre, a former professor and fellow at the Gaede Institute, Westmont College, and the author of Caring for Words in a Culture of Lies. Ms. McEntyre’s work also includes a series of books featuring poems inspired by the works of Van Gogh, Vermeer, and Rembrandt.

One evening over wine, cheese, and chocolate, we attempted to live out what she celebrates: taking the time to speak intentionally and listen generously.

—Naomi Biesheuvel, Brian Dijkema, and Kathryn de Ruijter

Comment: You’ve mentioned the idea that maybe we should start a slow-language movement, like the slow-food movement. What is your vision for a slow-language movement?

Marilyn Chandler McEntyre: I think about the people I have known who do speak slowly. It would have to do with being intentional about saying every word, letting every word have some space around it. I remember a professor of mine in college—a history professor—who spoke at about . . . this . . . pace. He didn’t pause, he didn’t use filler words like “uh,” and when he was finished you would hear the period at the end of every sentence. It was like hearing an adagio in music. I felt as if the classes and even the lunches we had with him were little retreats for the ear and the spirit. And I remember having the thought at the time that listening to Dr. Poland speak was hearing language on the gold standard. His sentences had full weight.

So my imagination goes to those lunches with Dr. Poland. I can imagine its being a lunchtime gathering where everyone would consent to be intentional about slowing down and hearing each other’s words, and not just “rabbiting on” as a British friend of mine puts it. That might be a place it could start.

Comment: I think some of us find masters of that kind of conversation intimidating to speak with, because we start to feel somewhat self-conscious about our own word choices. How do you deal with that?

MCM: Well, oddly, your question reminds me of another one of my professors. She was a French professor, Mme. Crosby. I lived in a language dorm where you had to speak a language other than English at one meal a day. When she came she would deliberately sit with the students in French 1 and French 2 and somehow she would elicit conversation from them. I have the recollection that it was her great cheerfulness and generous listening that accomplished that. She would spend time on the fragments of sentences that they managed to cobble together. So I do think that in a slow-language movement, if it were going to help people be more intentional about speaking in a way that honours speaking and hearing, some of that work would have to do with slow listening, too.

Some years ago, some friends and I got permission to do an experimental course called Conversational English for Native Speakers. We had such a good time. We had fourteen students and we read Jane Austen because the models of conversation in there aren’t just beautiful because they’re antique, they’re also vigorous. The combination of politesse and holding the other person’s feet to the fire is invigorating and surprising. The way they do call each other to account: “Mr. Darcy! No gentleman would say that!”

So in Conversational English we talked about the conversations in Pride and Prejudice at some length and looked at confrontation and respect for limits. When everybody knows the limits, and know themselves to be in a safe space, you can afford to be confrontational.

The final exam in our little course was to have seven people sit in a circle and we gave them a topic to start with. Everyone needed to speak, there needed to be follow-up questions. There were certain parameters that they needed to demonstrate.

One thing we really worked hard on was the follow-up question, so that once I ask you a question, and you answer it, I could pick up something in your answer to ask the next question about. This kind of follow-up seems to be missing from a lot of undergraduate conversation. They see so much conversation in public media where there’s a question-answer-spin, new question—only three or four strokes in what passes for debate or conversation. So prolonging the process was part of the point in our class.

Comment: Speaking of media, one of the things I was interested in is the distinction between bias and slant. It seems like quite a fine line.

MCM: I don’t actually think it’s that fine, except that many people use the word “bias” where I wouldn’t use it. I think of bias as where you represent an unacknowledged agenda as objective information, but you’re only presenting selective information. All of us have biases. But I guess I think that by definition, a bias is unexamined.

I think of A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn. Zinn says in the beginning, in effect, “This is going to be from the perspective of people who have not been the dominant culture. This is American history written from the underside.” He announces what he’s going to do. So when students read it and say, “This is so biased,” I think, well, he didn’t even pretend he was going to give that point of view.

Comment: Sort of like Comment, where we wear our slant proudly.

MCM: Exactly. I don’t think a strongly held position or opinion is biased, if you know why you’re there, you say why you’re there, you make it public that you are there.

Comment: Journalists are to some extent the first historians, but do you think news programs should take as a starting point a different slant? There are sections of the newspaper that are called “opinion,” but the front page is different. Is that just something that people have to learn as they read a publication, to say, oh, I understand that this is their slant?

MCM: I think it is inevitable that any public medium is going to have its colouration. But it does seem as though they should put their own journalistic standards out front. It would be good if the newspaper just had that there along with their list of editors: “These are the standards we attempt to meet. We hold our reporters accountable for these things.” I think the good ones do this to some extent, but of course they have their different slants.

I can read [certain publications] and not coming away fuming even though I don’t agree with some of their positions, because in their own terms they’ve been faithful to what they essentially announce they’re going to do. That’s all I would hold a journal accountable for: to be faithful to their statement of purpose.

Comment: It seems like a lot of people turn to online news, but then you run into the issue of things getting dumbed down sometimes.

MCM: Well, it’s interesting about the internet. Yes, things do get dumbed down, but also, independent reporting is really finding a new lease on life on the internet. [For instance,] Amy Goodman is a remarkably intelligent, well-spoken, gutsy, progressive news reporter. Her effort on Democracy Now is to represent stories that don’t make it to the network news media, so she airs a lot of stories about immigrant groups, stories about connecting the dots between multinational corporations and what’s happening in Bangladesh or Pakistan.

Comment: So it’s almost like the new standard for news is that instead of saying, “We’re going to be unbiased reporters,” it’s a matter of telling the story from your slant in the most truthful way you can?

MCM: Yes, and in a way that acknowledges what your agenda is. Also, I think the matter of funding is quite important. Following the money is fairly reliable way of making some judgement about the integrity of what’s being produced.

Comment: You talk about reading well and how to read critically. Do you feel like the students that you try to bring through this process with you—are they already questioning sources and questioning funding?

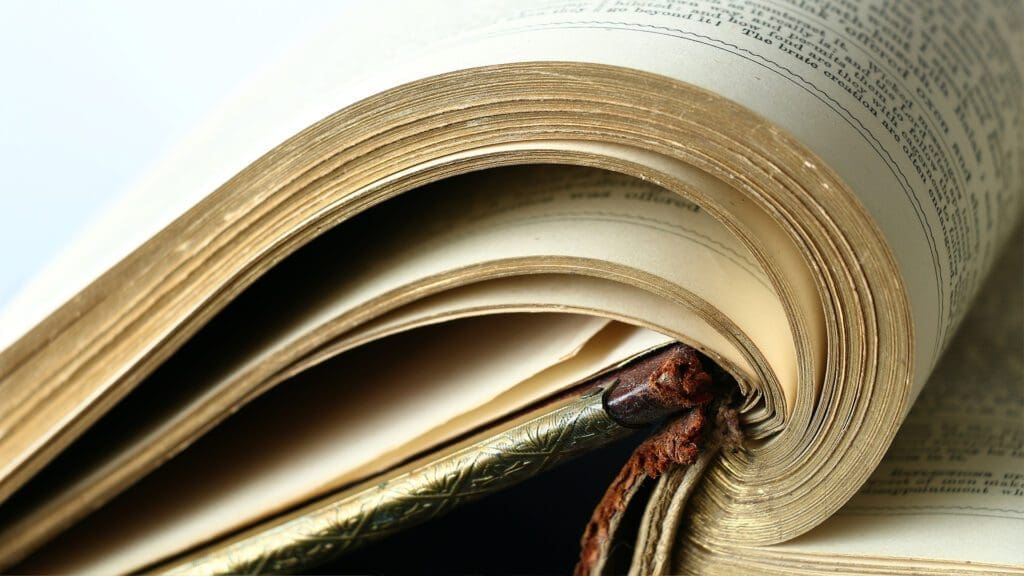

MCM: I think that a lot of the students I have taught have been subjected to a curriculum that is overfilled and classrooms that are overfilled, so I don’t want in any way to suggest that the students are slothful. They’ve been pushed through this massive number of texts and then they think that they’ve read the Iliad.

I find that in college teaching, a lot of what has to happen is that you slow them down. Let’s read it again. What does it mean to read? When you say you’ve read the book, what exactly do you mean? Everybody can use that kind of checkpoint system now and then. So reading and rereading, and slowing, and conversing about what you read, and widening your repertoire of questions you bring to what you read is an ongoing process. Do I think that students have had enough of that? No, but that’s part of the job.

Comment: It seems like you really value reading aloud, but I think a lot of people get nervous asking certain questions, or reading aloud. I don’t often sit down with my friends and say, “Let me read you this passage.” There’s some resistance in our culture to that kind of engagement with the written word.

MCM: That’s part of educators’ work—basically to say, I’m going to make this classroom as safe a space as possible. It’s going back to Austen again. If you’re in a safe space, and we all know what the rules are, and we are all committed to not violating those rules of polite discourse . . . then go at it! Then you should have the freedom to put something out there, listen to how someone else heard it, and have disagreement.

One of the things that sometimes bothered me about the kindly culture of the Christian college I was teaching at—and really lovely, smart people were there—is that there was a campus culture of niceness that I thought tended sometimes to suppress the kind of vigorous conversation you get in Jane Austen.

Comment: You see that in our culture more broadly. We’re very careful about disagreeing with people. What does that mean for people who are no longer in the English classroom?

MCM: Those of us who are in any position of leadership need to assume some leadership in creating conversational spaces where disagreement is welcomed and shepherded in such a way that it doesn’t just polarize. At some point I have to admit that there are limits to my own reading and that I have my own slant. I think you can do that with integrity. You can be vigorous and insistent about what your own assumptions are and what you base them on. But if someone brings up new information, you need to be willing to say, “Oh, that’s new information to me.”

Comment: You need to be willing to accept new information but if you’re giving new information, that takes grace as well; to allow that person to change their mind and still be in conversation.

MCM: It does take a kind of social contract that these days does not go without saying. And if you lived in Jane Austen’s England in small towns, I’m sure there was plenty of conflict. But there were things that everyone assumed that a gentleman would do or not do, or that ladies did or not do. And I do not hope to go back to eighteenth-century English mores and the class system, but I don’t think we can make those assumptions so clearly now, and so part of the work of leadership is to put them on the table, as we did in one church where my husband worked when the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, and feelings ran very high.

The church leadership decided to have a conversation about the U.S. invading Iraq because people were saying things behind each other’s backs and polarizing over political opinions. There were forty-eight people at the first meeting, and the ground rule was, every person here gets to say one thing briefly about where you are with this, and the rest of us are going to listen.

It’s kind of the Quaker process. At the beginning of a meeting for business, each person present says one thing and there’s even a little silence in between. It isn’t until everyone has spoken that anyone else gets to respond. Then at that point you can go back to something someone else has said.

But I remember their laying out very clearly just a few simple ground rules and acknowledging that this matter was highly emotionally charged. Some of them were deeply distressed, some of them had sons or daughters in the military, some of them had been pacifists since their youth, but our point here was to listen to each other and try to understand where each of us was, and it worked reasonably well. But I don’t know that we can do this kind of conversation any more without the meta-conversation.

Wherever adults gather, whether it’s in an affinity group or a Bible study or a book group, my feeling is that leadership at this point means, “Let’s talk a little about how we’re going to do this,” and not just assuming that we’re all smart people and we can have a conversation. I don’t think conversation is easy.

I do think Christian culture in America has lost the capacity to foster that kind of vigorous debate in a way that says, “You are completely safe, you are completely respected, and you are completely loved.” So now tell me what you think! My grandmother, who grew up in Virginia and was a very educated woman for her time, really was a product of another time, and she modelled this for me. She could say her strong opinions with a certain kind of good humour that communicated to people that they were welcome, and that her intention was not to drive them away. But I think you have to cultivate that, because we don’t live in a culture where that goes without saying.

Comment: I wonder if Christians sort of have a leg up on the rest of society in things like reading aloud, or of repeating certain things over and over and really considering the words, having moments of reflection and meditation, reading aloud. Do you think that give us a sense of responsibility in culture?

MCM: It should. And having this sacred text and all of the foundation stories in it, really having the book as a focal point in Protestant tradition that gets read aloud and proclaimed from the pulpit, puts a very high value on the word and it gathers people around the word, and at least once a week, everyone gets read to. That helps to keep something of that culture of hearing the word happening. And I think most families, if they’re not of a class that requires them to work three jobs to pay the rent, can read to their kids at night.

Reading aloud to each other has been a big part of my marriage. I’ve been interested in how often, when we have gatherings in our home, the conversation will lead to something where one of us will say, “Oh, that reminds me of something Jane Kenyon wrote in one of her poems.” We get it off the shelf and we read it aloud, and people are so surprised and grateful. So I guess part of the practice I’m suggesting is to just do that.

Comment: When you were talking about the gold standard of language, I wondered: economy of language can be very beautiful. It means you’re using the right word at the right time, you’re using only as many as you need. But I wondered, like with eating, is there ever a place for a certain gratuitousness of language?

MCM: Sure! I think when old friends get together and they have a lot of stories to tell, you start with “I haven’t seen you for ages!” And then you’re just at it for the next two hours. A lot of it is talk, talk, talk, talk, talk that’s reweaving the friendship because time has elapsed. So that’s one example of when it isn’t what is said so much as, I want to hear your voice, I want to revel in your presence.

And there are playful ways of poking at language. You know the FedEx guy who did the commercials by talking as fast as it was possible to talk? He subsequently did a recording called Ten Classics in Ten Minutes where he got a minute to tell the entire story of Moby Dick or Gone With the Wind. It was hysterically funny. There’s a something about speed, and playing with language, and shooting language at each other—playing with it like a ball—that’s really fun.

Comment: You talk about language and play, but in that you really are taking it very seriously. It’s actually doing language a lot of honour. It’s kind of like children, when you really take the time to play with them, it’s because you care. You’re paying attention then.

MCM: My daughter talks very quickly. She’s in business, so she’s developed the habit of being very efficient and saying a lot very quickly to get through the meeting with maximum material. But I admire the fact that she can still speak clearly, even though it’s fast. So I think there are lots of ways to use language effectively. We don’t all have to sound like Professor Poland, but that’s one of my objectives.